Abstract

The hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE promotes the expression of hepcidin, a circulating hormone produced by the liver that inhibits dietary iron absorption and macrophage iron release. HFE mutations are associated with impaired hepatic bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/SMAD signaling for hepcidin production. TMPRSS6, a transmembrane serine protease mutated in iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia, inhibits hepcidin expression by dampening BMP/SMAD signaling. In the present study, we used genetic approaches in mice to examine the relationship between Hfe and Tmprss6 in the regulation of systemic iron homeostasis. Heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 in Hfe−/− mice reduced systemic iron overload, whereas homozygous loss caused systemic iron deficiency and elevated hepatic expression of hepcidin and other Bmp/Smad target genes. In contrast, neither genetic loss of Hfe nor hepatic Hfe overexpression modulated the hepcidin elevation and systemic iron deficiency of Tmprss6−/− mice. These results indicate that genetic loss of Tmprss6 increases Bmp/Smad signaling in an Hfe-independent manner that can restore Bmp/Smad signaling in Hfe−/− mice. Furthermore, these results suggest that natural genetic variation in the human ortholog TMPRSS6 might modify the clinical penetrance of HFE-associated hereditary hemochromatosis, raising the possibility that pharmacologic inhibition of TMPRSS6 could attenuate iron loading in this disorder.

Introduction

Hereditary hemochromatosis associated with HFE mutation (HFE-HH) is a disorder of variable penetrance in which excessive absorption of dietary iron causes iron to accumulate in tissues; in some cases, cellular damage caused by iron leads to organ failure. HFE-HH is characterized by insufficient expression of hepcidin, a circulating peptide hormone produced by the liver in response to several physiologic stimuli, including iron loading. Hepcidin inhibits the absorption of dietary iron and the release of iron from macrophage stores by triggering the internalization and degradation of ferroportin, a cellular iron exporter present on the basolateral membrane of enterocytes and the plasma membrane of macrophages.1 Both patients with HFE-HH and Hfe knockout (Hfe−/−) mice exhibit hepcidin expression that is inappropriately low relative to their elevated body iron stores, explaining their excessive uptake of dietary iron.2-4 The hepcidin insufficiency in HFE-HH leads to a characteristic distribution of iron stores that is primarily hepatocellular and shows relative sparing of reticuloendothelial cells.5-7 Hepatic expression of a hepcidin transgene was found to inhibit iron accumulation in Hfe−/− mice,3 demonstrating that hepcidin insufficiency is central to the pathogenesis of HFE-HH.

The mechanism by which HFE promotes hepcidin expression is not fully understood. HFE, which shares structural homology with major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, heterodimerizes with β2-microglobulin.8 Studies in mouse models suggest that Hfe, which competes with transferrin for binding to transferrin receptor 1 (Tfr1),9 induces hepcidin expression when dissociated from Tfr1.10 In vitro studies suggest that interaction of HFE with TFR2, a homolog of TFR1, is also necessary for the induction of hepcidin expression by iron-loaded transferrin.11 Selective disruption of Hfe in hepatocytes causes hepatic iron overload and hepcidin suppression, indicating that Hfe promotes hepcidin expression in hepatocytes.12

The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/SMAD signaling pathway is a key pathway promoting hepcidin transcription by hepatocytes. Binding of BMPs, members of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily of ligands, to transmembrane receptors triggers phosphorylation of intracellular receptor-associated SMAD proteins that form a complex with the common mediator SMAD4, which then translocates to the nucleus to promote transcription of hepcidin and other target genes.13,14 In hepatocytes, BMP/SMAD signaling for hepcidin production is augmented by hemojuvelin (HJV), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein of the repulsive guidance molecule family that functions as a BMP coreceptor.14 Accordingly, HJV mutations in humans and mice lead to markedly decreased hepcidin levels associated with systemic iron overload.15-17 Loss of Bmp6 function in mice results in iron loading of similar severity, suggesting that BMP6 is the physiologic ligand for HJV.18,19

TMPRSS6, a transmembrane serine protease produced by the liver that is also known as matriptase-2, has recently emerged as a key inhibitor of hepatic BMP/SMAD signaling. In both humans and mice, TMPRSS6 mutations result in inappropriately elevated hepcidin expression, impaired intestinal iron absorption, and iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA).20-23 TMPRSS6 has been shown to cleave HJV from the plasma membrane in vitro, suggesting that TMPRSS6 modulates hepcidin transcription by down-regulating BMP/SMAD signaling.24 Accordingly, Tmprss6−/− mice show a reduction in hepatic mRNA encoding the Bmp6 ligand, which is consistent with the known transcriptional regulation of Bmp6 by iron,25 but show hepatic mRNA expression of Id1, a transcriptional target of Bmp6 signaling18,19 that is inappropriately elevated relative to their low hepatic iron stores and Bmp6 mRNA levels.26 In Tmprss6−/− mice, Hjv and Bmp6 are required to achieve this up-regulation of Bmp/Smad signaling.26-28

Recent reports indicate that BMP/SMAD signaling is impaired in HFE-HH. In livers of Hfe−/− mice, Bmp6 mRNA expression is up-regulated appropriately in response to the increased iron stores.29,30 However, phosphorylation of receptor-associated Smad proteins (Smad1/5/8) and expression of Id1 mRNA are inappropriately low in Hfe−/− livers relative to their hepatic iron stores and Bmp6 mRNA levels.29,30 Conversely, in wild-type mice, hepatic expression of an Hfe transgene was found to significantly increase hepatic mRNA encoding hepcidin, Id1 and Smad7,31 another Bmp6 transcriptional target.32 Expression of this Hfe transgene in livers of mice lacking the Bmp coreceptor Hjv did not yield a significant increase in hepcidin or Id1 mRNA.33 These findings suggest that HFE promotes hepcidin expression by interacting with the BMP/SMAD pathway genetically downstream from the BMP6 ligand in an HJV-dependent manner.

The opposing effects on BMP/SMAD signaling caused by genetic loss of HFE and TMPRSS6, respectively, raise the following possibilities: (1) reduction of TMPRSS6 activity might raise hepcidin expression and thus reduce systemic iron overload in HFE-HH, or (2) reduction of HFE activity might decrease hepcidin expression and thus rescue systemic iron deficiency in IRIDA. We used genetic approaches in mice to examine the relationship between Tmprss6 and Hfe in the regulation of hepcidin expression and systemic iron homeostasis.

Methods

Animal strains and care

Tmprss6−/− (B6.129P2-Tmprss6tm1Dgen/Crl) mice, which were generated at Deltagen and previously characterized by our laboratory,26 were backcrossed to C57BL/6N mice for at least 7 generations before study. Hfe−/− mice on a C57BL/6J background (B6-Hfetm2Nca)6 and mice overexpressing an Hfe transgene under control of the liver-specific transthyretin promoter B6-Tg(Ttr-Hfe)1Nca on an Hfe−/− C57BL/6J background,10 were previously generated by our laboratory. All mice were born and housed in the barrier facility at Duke University according to protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Animals were fed a 270 parts per million iron diet containing 150 parts per million fenbendazole for pinworm prophylaxis (5T40 Modified Laboratory Rodent Diet 5001zz; PMI Nutrition International). Food and water were provided ad libitum. Animals were genotyped for the wild-type and mutant Tmprss626 and Hfe34 alleles and for the Hfe transgene,10 by PCR performed on genomic DNA prepared from toe clips.35 Mice were analyzed at either 4 or 8 weeks of age. Because of sex-specific differences in iron homeostasis, only female mice were analyzed.

Iron analysis in blood and tissues

Serum and tissue nonheme iron concentrations were measured as described previously.36 Transferrin saturation was calculated by dividing serum iron concentration by total iron-binding capacity. Complete blood counts were performed on whole blood by the Duke University Veterinary Diagnostics Laboratory on a CellDyn 3700 (Abbott).

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Statistical analysis

Unpaired, 2-tailed Student t tests were performed in Microsoft Excel 2008 software. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Genetic loss of Tmprss6 modifies iron loading in 8-week-old Hfe−/− mice

To examine the effect of Tmprss6 deficiency on systemic iron homeostasis in Hfe−/− mice, we bred Tmprss6+/− mice to Hfe−/− mice, a model of HFE-HH.6 We generated F1 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/− mice, which we then interbred to yield F2 mice of all 9 possible Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations. These offspring were phenotyped at 8 weeks, an age when the murine growth rate has slowed and Hfe−/− mice exhibit significant hepatic iron overload.10

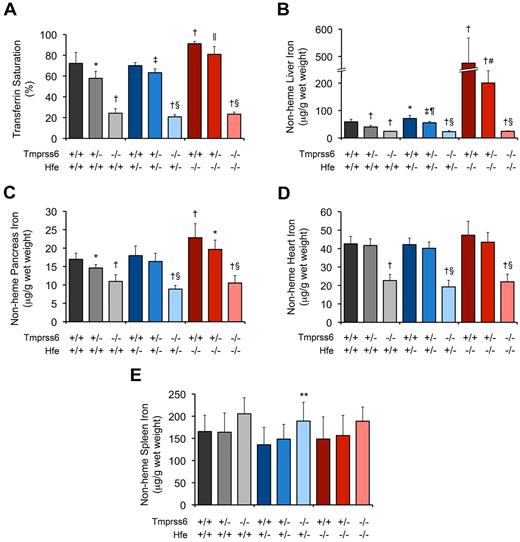

Consistent with prior studies of Hfe−/− mice,6,10,34 8-week-old Hfe−/− mice harboring 2 wild-type Tmprss6 alleles (Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice) showed serum iron concentration (SI; Table 1), serum transferrin saturation (TS; Figure 1A), liver nonheme iron concentration (LIC; Figure 1B), and pancreas nonheme iron concentration (Figure 1C) that were each significantly elevated compared with the corresponding parameters in wild-type (Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+) controls. Mean heart nonheme iron concentration was also higher in Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ controls, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .16; Figure 1D). Compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice, Hfe−/− mice with heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 (Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−) showed modest but significant reductions in both SI and TS and a large, significant reduction in LIC (Table 1; Figure 1A-B). Heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 also led to nonsignificant reductions in mean nonheme iron concentrations in the pancreas (P = .07; Figure 1C) and heart (P = .27; Figure 1D) of Hfe−/− mice. Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice showed spleen nonheme iron concentrations (Figure 1E) and peripheral RBC indices (Table 1) that were similar to Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ controls.

Physical, hematological, and serum parameters of 8-week-old mice of all Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations

| Genotype . | Body wt, g . | Whole blood . | Serum . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 1012/L . | Hgb, g/L . | Hct . | MCV, × 10−15/L . | MCH, pg . | RDW, % . | Iron, μM . | ||

| Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ | 19 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 149 ± 6 | 0.461 ± 0.011 | 50.3 ± 1.1 | 16.2 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 1.3 | 31.9 ± 6.2 |

| Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/− | 20 ± 1 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 146 ± 3 | 0.455 ± 0.011 | 48.2 ± 0.6* | 15.5 ± 0.3† | 18.3 ± 0.8 | 25.2 ± 3.6† |

| Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− | 18 ± 1† | 11.2 ± 0.4* | 95 ± 3* | 0.309 ± 0.007* | 27.7 ± 1.3* | 8.5 ± 0.3* | 40.3 ± 2.0* | 10.7 ± 2.5* |

| Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ | 20 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 153 ± 10 | 0.462 ± 0.023 | 50.4 ± 0.7 | 16.7 ± 0.7 | 17.4 ± 0.8 | 31.3 ± 3.3 |

| Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/− | 19 ± 1 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 149 ± 5 | 0.455 ± 0.016 | 50.2 ± 0.5 | 16.4 ± 0.4 | 17.7 ± 1.0 | 27.3 ± 2.1‡ |

| Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/− | 17 ± 1§ | 10.8 ± 0.2*§ | 95 ± 7*§ | 0.307 ± 0.008*§ | 28.3 ± 0.8*§ | 8.7 ± 0.6*§ | 38.5 ± 2.1*§ | 9.3 ± 1.2*§ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ | 19 ± 1 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 154 ± 5 | 0.476 ± 0.020 | 51.5 ± 0.6 | 16.7 ± 0.3 | 17.8 ± 0.6 | 41.4 ± 2.1† |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− | 19 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 153 ± 4 | 0.474 ± 0.006 | 51.4 ± 0.6 | 16.6 ± 0.5 | 17.6 ± 0.8 | 35.5 ± 4.3‖ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− | 19 ± 2§ | 10.8 ± 0.2*§ | 94 ± 6*§ | 0.302 ± 0.015*§ | 28.0 ± 1.2*§ | 8.7 ± 0.4*§ | 39.5 ± 2.4*§ | 10.9 ± 0.8*§ |

| Genotype . | Body wt, g . | Whole blood . | Serum . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 1012/L . | Hgb, g/L . | Hct . | MCV, × 10−15/L . | MCH, pg . | RDW, % . | Iron, μM . | ||

| Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ | 19 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 149 ± 6 | 0.461 ± 0.011 | 50.3 ± 1.1 | 16.2 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 1.3 | 31.9 ± 6.2 |

| Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/− | 20 ± 1 | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 146 ± 3 | 0.455 ± 0.011 | 48.2 ± 0.6* | 15.5 ± 0.3† | 18.3 ± 0.8 | 25.2 ± 3.6† |

| Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− | 18 ± 1† | 11.2 ± 0.4* | 95 ± 3* | 0.309 ± 0.007* | 27.7 ± 1.3* | 8.5 ± 0.3* | 40.3 ± 2.0* | 10.7 ± 2.5* |

| Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ | 20 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 153 ± 10 | 0.462 ± 0.023 | 50.4 ± 0.7 | 16.7 ± 0.7 | 17.4 ± 0.8 | 31.3 ± 3.3 |

| Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/− | 19 ± 1 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 149 ± 5 | 0.455 ± 0.016 | 50.2 ± 0.5 | 16.4 ± 0.4 | 17.7 ± 1.0 | 27.3 ± 2.1‡ |

| Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/− | 17 ± 1§ | 10.8 ± 0.2*§ | 95 ± 7*§ | 0.307 ± 0.008*§ | 28.3 ± 0.8*§ | 8.7 ± 0.6*§ | 38.5 ± 2.1*§ | 9.3 ± 1.2*§ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ | 19 ± 1 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 154 ± 5 | 0.476 ± 0.020 | 51.5 ± 0.6 | 16.7 ± 0.3 | 17.8 ± 0.6 | 41.4 ± 2.1† |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− | 19 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.1 | 153 ± 4 | 0.474 ± 0.006 | 51.4 ± 0.6 | 16.6 ± 0.5 | 17.6 ± 0.8 | 35.5 ± 4.3‖ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− | 19 ± 2§ | 10.8 ± 0.2*§ | 94 ± 6*§ | 0.302 ± 0.015*§ | 28.0 ± 1.2*§ | 8.7 ± 0.4*§ | 39.5 ± 2.4*§ | 10.9 ± 0.8*§ |

Complete blood counts and SI were measured in 8-week-old female mice. For each parameter shown, the number of mice per genotype analyzed was as follows, with exceptions shown in parentheses: 6 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ (7 for SI), 8 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/−, 5 Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/− (9 for SI), 8 Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− (8 for SI), and 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Hct indicates hematocrit; and RDW, red cell distribution width.

P < .005 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice.

P < .05 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice.

P < .05 compared with Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

P not significant compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− mice.

P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

Tmprss6 deficiency modifies systemic iron homeostasis in 8-week-old Hfe−/− mice. (A-E) Analysis of serum and tissue iron parameters in 8-week-old female mice of all Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations. Graphed are mean values obtained from analyses of TS (A) and nonheme iron concentrations of liver (B), pancreas (C), heart (D), and spleen (E). For each parameter shown, the number of mice per genotype analyzed was as follows, with exceptions shown in parentheses: 7 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/−, 5 Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−, 9 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ (8 for TS), 9 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/−, 8 Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. Error bars represent SD. *P < .05 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+; †P < .005 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+; ‡P < .005 compared with Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+; §P not significant compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−; ‖P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+; ¶P < .005 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/−; #P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+; and **P < .05 compared with Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

Tmprss6 deficiency modifies systemic iron homeostasis in 8-week-old Hfe−/− mice. (A-E) Analysis of serum and tissue iron parameters in 8-week-old female mice of all Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations. Graphed are mean values obtained from analyses of TS (A) and nonheme iron concentrations of liver (B), pancreas (C), heart (D), and spleen (E). For each parameter shown, the number of mice per genotype analyzed was as follows, with exceptions shown in parentheses: 7 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/−, 5 Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−, 9 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ (8 for TS), 9 Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/−, 8 Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. Error bars represent SD. *P < .05 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+; †P < .005 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+; ‡P < .005 compared with Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+; §P not significant compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−; ‖P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+; ¶P < .005 compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/−; #P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+; and **P < .05 compared with Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

Whereas heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 reduced systemic iron overload in Hfe−/− mice, homozygous loss of Tmprss6 caused systemic iron deficiency. Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice showed SI (Table 1), TS (Figure 1A), and nonheme iron concentrations of liver (Figure 1B), pancreas (Figure 1C), and heart (Figure 1D) that were significantly decreased compared with wild-type (Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+) controls. These results demonstrate that Tmprss6 is a powerful genetic modifier of the hemochromatosis phenotype in Hfe−/− mice.

The reduced SI, TS, and nonheme iron concentrations of liver, pancreas, and heart measured in Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice were similar to the levels present in Tmprss6−/− mice with 1 or 2 wild-type Hfe alleles (Table 1; Figure 1A-D). Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/−, and Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− mice showed similar RBC indices that were consistent with iron deficiency anemia (Table 1), and all 3 genotypes developed truncal alopecia (data not shown), a phenotype known to reflect systemic iron deficiency in Tmprss6 mouse mutants.20,22 Thus, the systemic iron deficiency of Tmprss6−/− mice was not altered by the Hfe genotype. Spleen nonheme iron concentrations in Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, Hfe+/−Tmprss6−/−, and Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− mice were similar and were not significantly higher than Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ levels (Figure 1E).

Interestingly, small but significant increases in LIC were detected in Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ mice compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice and in Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/− mice compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/− mice (Figure 1B). Thus, whereas Hfe genotype did not affect serum and tissue iron concentrations of Tmprss6−/− mice, Hfe genotype did affect LIC of mice with at least 1 wild-type Tmprss6 allele.

Homozygous loss of Tmprss6 up-regulates hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling in Hfe−/− mice

We next sought to determine whether the ability of Tmprss6 to modify systemic iron homeostasis in Hfe−/− mice was correlated with its ability to inhibit hepcidin expression. For this analysis, we focused on mice of selected Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations showing high LIC (Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−) and low LIC (Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−), as well as wild-type (Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+) controls.

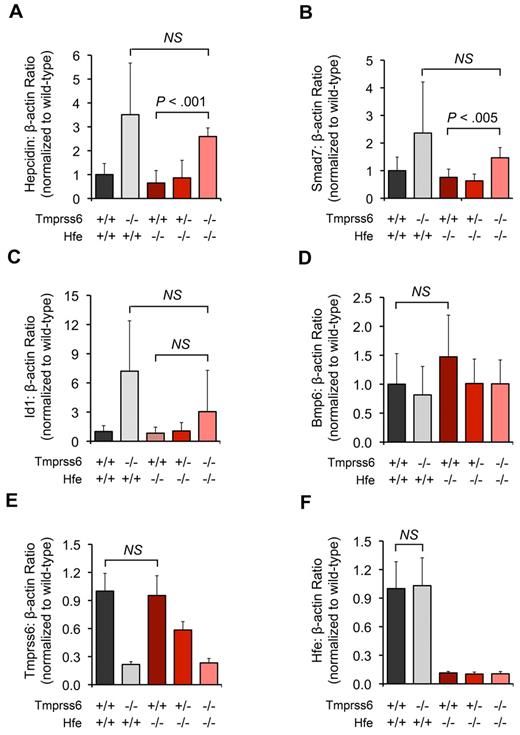

In both Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice, hepatic mRNA levels of hepcidin were similar to Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice and thus were inappropriately reduced relative to hepatic iron stores (Figure 2A). Hepatic mRNA levels of 2 Bmp6 transcriptional targets, Smad7 (Figure 2B) and Id1 (Figure 2C), were also similar in Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice. Compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice, however, Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice showed significant elevations in hepcidin and Smad7 mRNA and a nonsignificant increase in Id1 mRNA (P = .26; Figure 2A-C). Notably, the hepcidin, Smad7, and Id1 levels of Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice were not significantly different from Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− levels, consistent with their similar parameters of iron deficiency measured in blood and tissues. Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice showed a trend toward higher Bmp6 mRNA levels compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ controls (P = .17; Figure 2D), which is compatible with reports that hepatic Bmp6 mRNA expression correlates with hepatic iron burden in Hfe−/− mice.29,30

Homozygous loss of Tmprss6 up-regulates hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling in Hfe−/− mice. (A-F) Analysis of mRNA expression of genes involved in hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling in 8-week-old female mice of selected Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations. Graphed is the mean mRNA expression of hepcidin (Hamp; A), Smad7 (B), Id1 (C), Bmp6 (D), Tmprss6 (E), and Hfe (F), relative to β-actin (Actb). mRNA expression ratios are normalized to an Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mean value of 1. For each parameter shown, the number of mice per genotype analyzed was 7 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+, 5 Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. Error bars represent SD. NS indicates not significant. In panel E, the low level of Tmprss6 mRNA detected in mice with homozygous loss of Tmprss6 reflects the known, low-level expression of a partial transcript from the targeted Tmprss6 locus.26

Homozygous loss of Tmprss6 up-regulates hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling in Hfe−/− mice. (A-F) Analysis of mRNA expression of genes involved in hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling in 8-week-old female mice of selected Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations. Graphed is the mean mRNA expression of hepcidin (Hamp; A), Smad7 (B), Id1 (C), Bmp6 (D), Tmprss6 (E), and Hfe (F), relative to β-actin (Actb). mRNA expression ratios are normalized to an Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mean value of 1. For each parameter shown, the number of mice per genotype analyzed was 7 Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+, 5 Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. Error bars represent SD. NS indicates not significant. In panel E, the low level of Tmprss6 mRNA detected in mice with homozygous loss of Tmprss6 reflects the known, low-level expression of a partial transcript from the targeted Tmprss6 locus.26

These results suggest that homozygous loss of Tmprss6 in Hfe−/− mice increases hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling for hepcidin production at a point downstream of the Bmp6 ligand, leading to decreased intestinal iron absorption and systemic iron deficiency. Thus, Hfe is not required to achieve the elevated hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling caused by genetic loss of Tmprss6. Hepatic Tmprss6 mRNA levels were similar in Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice (Figure 2E), suggesting that transcription of Tmprss6 is not dependent on Hfe function and is not altered in the setting of elevated LIC. Likewise, hepatic Hfe mRNA levels were similar in Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− mice (Figure 2F), suggesting that the transcription of Hfe is not dependent on Tmprss6 function and is not altered in the setting of decreased LIC.

Whereas homozygous loss of Tmprss6 raised Bmp6 target gene expression in Hfe−/− mice, homozygous loss of Tmprss6 did not yield a detectable increase in the phosphorylation of Smads 1, 5, and 8, which function as intracellular mediators of Bmp6 signaling,19 in liver lysates prepared from either Hfe+/+ or Hfe−/− mice (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). This apparent discrepancy might be explained if the kinetics of Smad phosphorylation were relatively transient compared with target gene expression or if signal amplification occurred during transduction through the Bmp/Smad pathway, as has been proposed previously.30

Although homozygous loss of Tmprss6 did not produce a significant increase in spleen nonheme iron concentration in Hfe−/− mice (Figure 1E), we considered that measurements performed in whole spleen might lack sufficient sensitivity to reflect changes in iron content occurring primarily within the splenic macrophage cell subpopulation. Indeed, histologic assessment of mice of selected Hfe-Tmprss6 genotype combinations suggested differences in iron accumulation in splenic macrophages that were compatible with the observed differences in hepcidin expression. Compared with Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 2A), Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice showed reduced iron stores in splenic macrophages (supplemental Figure 2B), whereas iron stores in splenic macrophages appeared similarly increased in Hfe+/+Tmprss6−/− (supplemental Figure 2C) and Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− (supplemental Figure 2D) mice.

Whereas Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice did not differ significantly in measured parameters of hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling, their significant differences in both SI and TS suggest that these genotypes might harbor a subtle difference in hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling that was difficult to detect because of hepcidin-modulating factors such as circadian variation and iron ingestion.38-40 In a similar manner, we suggest that the much smaller differences in LICs detected between Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice and between Hfe+/−Tmprss6+/− and Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/− mice (Figure 1B) may reflect the effects of small but physiologically significant changes in hepcidin expression that can be achieved by Hfe under conditions in which some Tmprss6 is present to modulate Bmp/Smad signaling. However, we expect that study of considerably larger animal groups would be required to provide sufficient power to demonstrate these potentially very small differences in hepcidin expression because (1) in the current study, the difference in hepcidin expression did not reach significance between Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe+/+Tmprss6+/+ mice, which differ markedly in LIC, and (2) in a previous study, we found that the difference in hepcidin expression did not reach significance between 8-week-old Tmprss6+/+ and Tmprss6+/− mice with 2 wild-type Hfe alleles.26

Heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 raises hepcidin expression in younger Hfe−/− mice

We hypothesized that the effect of heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 on hepcidin expression might be more pronounced at a younger age, which could explain the development of the significantly different LICs observed in Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice at 8 weeks. To test this, we used a multigenerational breeding strategy to generate Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice, which we interbred to yield Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− offspring for phenotypic characterization at 4 weeks of age.

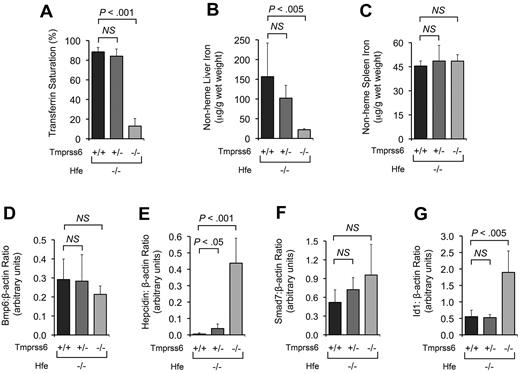

At 4 weeks of age, the differences in SI, TS, LIC, spleen nonheme iron concentration, and hepatic Bmp6 mRNA between Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice did not reach statistical significance (Table 2; Figure 3A-D). However, compared with age-matched Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ controls, 4-week-old Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice showed a significant increase in hepatic hepcidin mRNA (Figure 3E) and a trend toward increased hepatic Smad7 mRNA (P = .10; Figure 3F). Thus, the reduction in LIC detected at 8 weeks of age in Hfe−/− mice with heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 was preceded by an elevation in hepcidin expression at a younger age.

Physical, hematological, and serum parameters of 4-week-old Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice

| Genotype . | Body wt, g . | Whole blood . | Serum . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 1012/L . | Hgb, g/L . | Hct . | MCV, × 10−15/L . | MCH, pg . | RDW, % . | Iron, μM . | ||

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ | 15 ± 2 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 136 ± 11 | 0.419 ± 0.030 | 55.5 ± 0.7 | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 20.0 ± 3.1 | 38.4 ± 3.7 |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− | 16 ± 2 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 141 ± 8 | 0.436 ± 0.024 | 54.6 ± 1.2 | 17.6 ± 0.5 | 18.7 ± 2.2 | 37.3 ± 5.8 |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− | 13 ± 1*† | 7.4 ± 0.5‡ | 89 ± 4§† | 0.291 ± 0.019§† | 39.4 ± 0.7§† | 12.2 ± 0.2§† | 37.0 ± 3.2§† | 5.3 ± 3.5§† |

| Genotype . | Body wt, g . | Whole blood . | Serum . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 1012/L . | Hgb, g/L . | Hct . | MCV, × 10−15/L . | MCH, pg . | RDW, % . | Iron, μM . | ||

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ | 15 ± 2 | 7.6 ± 0.5 | 136 ± 11 | 0.419 ± 0.030 | 55.5 ± 0.7 | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 20.0 ± 3.1 | 38.4 ± 3.7 |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− | 16 ± 2 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 141 ± 8 | 0.436 ± 0.024 | 54.6 ± 1.2 | 17.6 ± 0.5 | 18.7 ± 2.2 | 37.3 ± 5.8 |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− | 13 ± 1*† | 7.4 ± 0.5‡ | 89 ± 4§† | 0.291 ± 0.019§† | 39.4 ± 0.7§† | 12.2 ± 0.2§† | 37.0 ± 3.2§† | 5.3 ± 3.5§† |

Complete blood counts and SI were measured in 4-week-old female mice. The numbers of mice per genotype analyzed were: 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Hct indicates hematocrit; and RDW, red cell distribution width.

P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice.

P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− mice.

P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

Tmprss6 deficiency modifies systemic iron homeostasis in 4-week-old Hfe−/− mice. (A-C) Effect of Tmprss6 genotype on serum and tissue iron parameters of 4-week-old female Hfe−/− mice. Graphed are mean values obtained from analyses of TS (A), LIC (B), and spleen nonheme iron concentration (C) in 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. (D-G) Effect of Tmprss6 genotype on hepatic mRNA expression of genes involved in Bmp/Smad signaling in 4-week-old female Hfe−/− mice. Graphed is the mean mRNA expression of Bmp6 (D), hepcidin (Hamp; E), Smad7 (F), and Id1 (G) relative to β-actin (Actb) in 6 mice per genotype. Error bars represent SD. NS indicates not significant.

Tmprss6 deficiency modifies systemic iron homeostasis in 4-week-old Hfe−/− mice. (A-C) Effect of Tmprss6 genotype on serum and tissue iron parameters of 4-week-old female Hfe−/− mice. Graphed are mean values obtained from analyses of TS (A), LIC (B), and spleen nonheme iron concentration (C) in 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, and 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. (D-G) Effect of Tmprss6 genotype on hepatic mRNA expression of genes involved in Bmp/Smad signaling in 4-week-old female Hfe−/− mice. Graphed is the mean mRNA expression of Bmp6 (D), hepcidin (Hamp; E), Smad7 (F), and Id1 (G) relative to β-actin (Actb) in 6 mice per genotype. Error bars represent SD. NS indicates not significant.

Compared with age-matched Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice, 4-week-old Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice showed marked, significant reductions in SI, TS, and LIC, and they displayed RBC indices consistent with iron deficiency anemia (Table 2; Figure 3A-B). Compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ controls, 4-week-old Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice showed significant elevations in hepatic hepcidin and Id1 mRNA (Figure 3E,G), and they showed trends toward decreased Bmp6 mRNA (P = .15; Figure 3D) and increased Smad7 mRNA (P = .09; Figure 3F). Despite their hepcidin elevation, 4-week-old Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice did not show evidence of increased spleen nonheme iron concentration compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ and Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− controls (Figure 3C), perhaps because only a limited number of senescent RBCs had been phagocytosed by splenic macrophages at this age. Interestingly, whereas complete genetic loss of Tmprss6 led to significant increases in both hepcidin and Id1 mRNA, the resulting induction was much greater for hepcidin than Id1. This result suggests that Id1 transcription might be comparatively less sensitive to hepatic Bmp/Smad signaling, which might explain why heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 did not yield a detectable increase in hepatic Id1 mRNA in Hfe−/− mice at this age (Figure 3G). The lack of a direct correlation between Id1 and hepcidin mRNA expression might also reflect influences of opposing pathways that participate in Id1 transcriptional regulation.41

Hepatic overexpression of Hfe does not exacerbate iron deficiency caused by homozygous loss of Tmprss6

Having found that Hfe deficiency did not alter iron parameters in Tmprss6−/− mice, we wondered if hepatic overexpression of Hfe would exacerbate the systemic iron deficiency of Tmprss6−/− mice by causing a further elevation in hepcidin expression. Using a multigenerational breeding strategy, we generated Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− male mice carrying a liver-specific Hfe transgene (Hfe tg) known to induce hepcidin expression in Hfe−/− mice.10 We bred these males to Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− females to yield Hfe−/− offspring that harbored 0, 1, or 2 mutant Tmprss6 alleles and were also either null or hemizygous for the Hfe transgene. We phenotyped these offspring at 8 weeks of age.

Consistent with prior study of Hfe−/− mice carrying the Hfe transgene,10 hepatic overexpression of Hfe in Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice produced RBC indices consistent with iron deficiency anemia (Table 3) and significant decreases in SI (Table 3), TS (Figure 4A), and LIC (Figure 4B). Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice with the Hfe transgene had LIC levels similar to Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice; in Hfe−/− mice carrying the Hfe transgene, LIC was not altered by the Tmprss6 genotype (Figure 4B).

Physical, hematological, and serum parameters of 8-week-old Hfe−/− mice harboring 0, 1, or 2 mutant Tmprss6 alleles that are also either null or hemizygous for a liver-specific Hfe transgene

| Genotype . | Body wt, g . | Whole blood . | Serum . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 1012/L . | Hgb, g/L . | Hct . | MCV, × 10−15/L . | MCH, pg . | RDW, % . | Iron, μM . | ||

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ | 19 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 159 ± 8 | 0.484 ± 0.021 | 52.7 ± 1.1 | 17.3 ± 0.9 | 17.8 ± 1.0 | 41.4 ± 3.4 |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− | 19 ± 1 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 158 ± 5 | 0.480 ± 0.019 | 51.5 ± 0.5* | 17.0 ± 0.7 | 17.5 ± 1.0 | 32.3 ± 4.3† |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− | 18 ± 1* | 11.3 ± 0.4† | 102 ± 8† | 0.327 ± 0.022† | 28.8 ± 1.4† | 9.0 ± 0.5† | 44.1 ± 3.8† | 10.7 ± 2.3† |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg | 19 ± 2 | 10.3 ± 0.4‡ | 115 ± 3‡ | 0.360 ± 0.011§ | 35.1 ± 1.6‡ | 11.2 ± 0.4‡ | 33.7 ± 2.0‡ | 11.5 ± 2.5‖ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg | 19 ± 1 | 10.7 ± 0.6§ | 111 ± 3§¶ | 0.352 ± 0.014§ | 32.9 ± 2.3‡¶ | 10.4 ± 0.5‡# | 36.1 ± 3.1‡ | 11.7 ± 2.5‖ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg | 18 ± 2 | 11.1 ± 0.3‖# | 99 ± 5‖# | 0.319 ± 0.012‖# | 28.9 ± 0.7‖# | 9.0 ± 0.2‖# | 44.8 ± 4.1‖# | 9.8 ± 2.0‖ |

| Genotype . | Body wt, g . | Whole blood . | Serum . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC, × 1012/L . | Hgb, g/L . | Hct . | MCV, × 10−15/L . | MCH, pg . | RDW, % . | Iron, μM . | ||

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ | 19 ± 1 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 159 ± 8 | 0.484 ± 0.021 | 52.7 ± 1.1 | 17.3 ± 0.9 | 17.8 ± 1.0 | 41.4 ± 3.4 |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− | 19 ± 1 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 158 ± 5 | 0.480 ± 0.019 | 51.5 ± 0.5* | 17.0 ± 0.7 | 17.5 ± 1.0 | 32.3 ± 4.3† |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− | 18 ± 1* | 11.3 ± 0.4† | 102 ± 8† | 0.327 ± 0.022† | 28.8 ± 1.4† | 9.0 ± 0.5† | 44.1 ± 3.8† | 10.7 ± 2.3† |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg | 19 ± 2 | 10.3 ± 0.4‡ | 115 ± 3‡ | 0.360 ± 0.011§ | 35.1 ± 1.6‡ | 11.2 ± 0.4‡ | 33.7 ± 2.0‡ | 11.5 ± 2.5‖ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg | 19 ± 1 | 10.7 ± 0.6§ | 111 ± 3§¶ | 0.352 ± 0.014§ | 32.9 ± 2.3‡¶ | 10.4 ± 0.5‡# | 36.1 ± 3.1‡ | 11.7 ± 2.5‖ |

| Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg | 18 ± 2 | 11.1 ± 0.3‖# | 99 ± 5‖# | 0.319 ± 0.012‖# | 28.9 ± 0.7‖# | 9.0 ± 0.2‖# | 44.8 ± 4.1‖# | 9.8 ± 2.0‖ |

Complete blood counts and SI were measured in 8-week-old female mice. For each parameter shown, the number of mice per genotype analyzed was as follows, with exceptions shown in parentheses: 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/− (8 for SI), 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− (6 for SI), 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg (6 for SI), 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg (8 for SI), and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Hfe tg indicates the liver-specific Hfe transgene; Hct, hematocrit; and RDW, red cell distribution width.

P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice.

P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice.

P value not significant compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice.

P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg mice.

P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg mice.

Hepatic overexpression of Hfe does not exacerbate the systemic iron deficiency caused by homozygous loss of Tmprss6. (A-E) Analyses of TS, tissue iron concentrations, and hepatic hepcidin mRNA expression in 8-week-old female Hfe−/− mice harboring 0, 1, or 2 mutant Tmprss6 alleles that are also either null or hemizygous for a liver-specific Hfe transgene. Graphed are mean values obtained from analyses of TS (A), LIC (B), heart nonheme iron concentration (C), hepcidin mRNA expression relative to β-actin (Actb) expression (D), and spleen nonheme iron concentration (E). In panel A, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg, and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg mice were analyzed. In panels B, C, and E, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg, and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg mice were analyzed. In panel D, 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg, and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg mice were analyzed. Error bars represent SD. Hfe tg indicates Hfe transgene. *P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+; †P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−; ‡P value not significant compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−; §P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg; ‖P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, and ¶P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

Hepatic overexpression of Hfe does not exacerbate the systemic iron deficiency caused by homozygous loss of Tmprss6. (A-E) Analyses of TS, tissue iron concentrations, and hepatic hepcidin mRNA expression in 8-week-old female Hfe−/− mice harboring 0, 1, or 2 mutant Tmprss6 alleles that are also either null or hemizygous for a liver-specific Hfe transgene. Graphed are mean values obtained from analyses of TS (A), LIC (B), heart nonheme iron concentration (C), hepcidin mRNA expression relative to β-actin (Actb) expression (D), and spleen nonheme iron concentration (E). In panel A, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg, and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg mice were analyzed. In panels B, C, and E, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, 9 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg, and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg mice were analyzed. In panel D, 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+, 7 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−, 6 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/−Hfe tg, and 8 Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−Hfe tg mice were analyzed. Error bars represent SD. Hfe tg indicates Hfe transgene. *P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+; †P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−; ‡P value not significant compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/−; §P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg; ‖P < .005 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+Hfe tg, and ¶P < .05 compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice.

The iron deficiency anemia caused by Hfe overexpression, however, was slightly less severe than the iron deficiency anemia caused by homozygous loss of Tmprss6 (Table 3). In Hfe−/− mice with the Hfe transgene, heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 caused small but significant reductions in hemoglobin (Hgb), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH). Homozygous loss of Tmprss6 in Hfe−/− mice with the Hfe transgene further reduced Hgb, MCV, and MCH to levels similar to those observed in Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice. Interestingly, the changes in TS and heart nonheme iron concentration appeared to mirror the subtle differences in Hgb, MCV, and MCH observed in these iron-deficient genotypes (Figure 4A,C; Table 3).

Hepatic hepcidin mRNA levels were similar in Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice regardless of Hfe transgene status (P = .61; Figure 4D), which is consistent with the similar RBC indices, SI, and TS displayed by these genotypes and shows that the hepcidin-inducing effects caused by overexpression of Hfe and homozygous loss of Tmprss6 were not additive. Interestingly, Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice did show a trend toward higher hepcidin expression compared with Hfe−/−Tmprss6+/+ mice with the Hfe transgene (P = .06; Figure 4D), which might explain the slightly increased severity of their iron deficiency anemia (Table 3). mRNA levels of the Hfe transgene were not altered by the Tmprss6 genotype (supplemental Figure 3).

Interestingly, whereas the presence of the Hfe transgene did not alter hepcidin levels in Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice, the presence of the transgene was associated with a trend toward higher spleen nonheme iron concentration in Hfe−/−Tmprss6−/− mice (P = .06; Figure 4E), which appeared to correspond histologically to a qualitative increase in splenic macrophage iron stores (supplemental Figure 4). Given that Hfe function in macrophages has been reported to influence splenic iron concentration,42 we considered that expression of the Hfe transgene in spleen might contribute to the observed trend in splenic nonheme iron concentrations. However, Hfe transgene expression was not detected in splenic mRNA in a prior study,10 and using the more sensitive method of quantitative RT-PCR, we were also unable to detect splenic transgene expression in the current study (data not shown). We suggest that the observed trends in splenic macrophage iron accumulation might reflect nonphysiologic effects related to hepatic Hfe overexpression or to physiologic effects of Hfe that are distinct from its role in hepcidin regulation.

Discussion

Insufficient expression of hepcidin, a key iron-regulatory hormone that inhibits the absorption of dietary iron and the release of iron from macrophage stores, is a central feature in the pathogenesis of HFE-HH. Recent studies conducted in mouse models suggest that the hepcidin insufficiency in HFE-HH is correlated with an impairment of BMP/SMAD signaling,29,30 a key pathway that promotes hepcidin transcription in hepatocytes.14 In the present study, we found that in Hfe−/− mice assessed at 8 weeks of age, heterozygous loss of the hepatic transmembrane serine protease Tmprss6, an inhibitor of Bmp/Smad signaling, markedly reduced the severity of systemic iron overload, whereas homozygous loss of Tmprss6 led to systemic iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Hfe−/− mice with complete loss of Tmprss6 showed elevations in hepatic mRNA encoding hepcidin and the Bmp6 transcriptional targets Id1 and Smad7. Given prior in vitro results demonstrating that TMPRSS6 cleaves HJV from the plasma membrane,24 our results suggest that by increasing the amount of Hjv on the hepatocyte plasma membrane, loss of Tmprss6 activity can restore Bmp/Smad signaling in Hfe−/− mice.

In previous studies, transcription of both Id1 and Smad7 was shown to be positively correlated with liver iron burden in a manner similar to transcription of hepcidin and Bmp6.25 Both liver-specific inactivation of the common mediator Smad425 and global disruption of Bmp619 were shown to cause significant reductions in hepatic Id1 and Smad7 mRNA levels, suggesting that the regulation of Id1 and Smad7 transcription in response to liver iron burden is mediated through Bmp6/Smad signaling. Therefore, our finding that Hfe−/− mice with homozygous loss of Tmprss6 showed increased mean hepatic Id1 and Smad7 mRNA even though they showed low LIC appears to be consistent with the role of Tmprss6 as an inhibitor of Bmp6/Smad signaling.24,26-28 Interestingly, a recent in vitro study suggested that Smad7 functions to inhibit hepcidin transcription.32 Whereas our results here do not exclude a role for Smad7 in hepcidin suppression, they do show that the transcriptional up-regulation of Smad7 caused by loss of Tmprss6 in vivo is not sufficient to repress hepcidin mRNA to wild-type levels.

Interestingly, heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 did not significantly alter hepatic hepcidin, Id1, or Smad7 expression when measured in Hfe−/− mice at 8 weeks of age; however, heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 did result in a significant increase in hepatic hepcidin mRNA and a trend toward increased Smad7 expression when measured in Hfe−/− mice at 4 weeks of age. We suspect that the attenuated hepatic iron loading observed in Hfe−/− mice with heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 at 8 weeks results from an elevation in Bmp/Smad signaling for hepcidin production that is present at an earlier age. However, based on the available data, we cannot exclude the possibility that the ability of heterozygous loss of Tmprss6 to modify iron loading in Hfe−/− mice results from an additional role of Tmprss6 in hepcidin suppression that is independent of the Bmp/Smad pathway. Whereas Hfe−/− mice showed marked iron loading in the liver, they showed only modest iron loading in the pancreas and heart at 8 weeks of age. Thus, Hfe−/− mice may not fully recapitulate the features of HFE-HH seen in humans, a difference that may reflect the effects of species-specific genetic modifiers.

Whereas we found that Tmprss6 strongly modifies the hemochromatosis phenotype of Hfe−/− mice, we conversely found that the IRIDA-like phenotype of Tmprss6−/− mice was not altered by Hfe mutation status. In particular, Tmprss6−/− mice with 0, 1, or 2 mutant Hfe alleles showed similar RBC indices and similarly decreased concentrations of iron in serum and tissues. Mice with complete loss of both Tmprss6 and Hfe showed elevations of hepatic hepcidin, Id1, and Smad7 that were similar to elevations achieved in mice with loss of Tmprss6 alone, demonstrating that Hfe is not required to generate the elevated Bmp/Smad signaling that results from the absence of Tmprss6. However, in mice with at least 1 wild-type Tmprss6 allele, we found that loss of even 1 wild-type Hfe allele was sufficient to cause small but significant increases in LIC, which we suspect reflect the effects of modest but physiologically significant changes in hepcidin expression. In addition, we found that hepatic overexpression of Hfe did not worsen the systemic iron deficiency present in Tmprss6−/− mice.

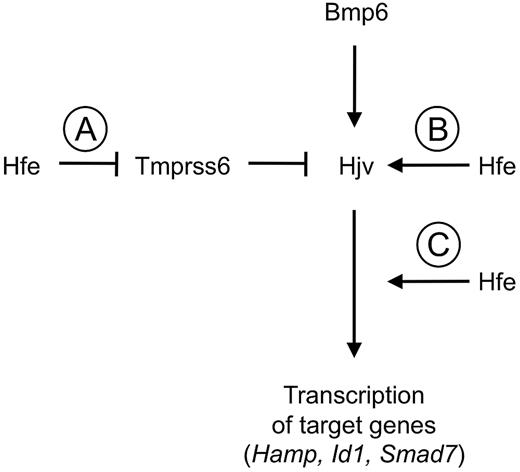

In future studies, the relationship between Hfe and the Bmp/Smad pathway remains to be clarified. However, in the context of prior studies implicating Hfe as a positive regulator of hepcidin expression that intersects with the Bmp/Smad pathway genetically downstream from Hjv,29-31 our results suggest a model that could explain the relationship between Hfe, Tmprss6, and the Bmp/Smad pathway (Figure 5). Our findings that the hepcidin elevation and systemic iron deficiency present in Tmprss6−/− mice were not altered by either Hfe mutation or Hfe overexpression could be compatible with a model in which Hfe acts genetically upstream of Tmprss6 to promote hepcidin expression. In this model, Hfe activity would reduce the activity of Tmprss6, which would in turn increase the density of Hjv on the hepatocyte plasma membrane and thus promote Bmp/Smad signaling for hepcidin production. Hfe might inhibit Tmprss6 activity through a direct interaction or alternatively through the action of an intermediate molecule(s).

Model of relationship among Hfe, Tmprss6, and the Bmp/Smad signaling pathway in hepcidin regulation. Our data are compatible with a model in which Hfe promotes Bmp/Smad signaling for hepcidin production by inhibiting the activity of Tmprss6 (A). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that Hfe promotes Bmp/Smad signaling by a mechanism that is independent of Tmprss6 but nevertheless cannot achieve a further elevation in Bmp/Smad target gene expression when Tmprss6 is absent. Hfe might, for example, promote Bmp/Smad signaling by Hjv (B) or promote Bmp/Smad signaling at a point functionally downstream of Tmprss6 (C).

Model of relationship among Hfe, Tmprss6, and the Bmp/Smad signaling pathway in hepcidin regulation. Our data are compatible with a model in which Hfe promotes Bmp/Smad signaling for hepcidin production by inhibiting the activity of Tmprss6 (A). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that Hfe promotes Bmp/Smad signaling by a mechanism that is independent of Tmprss6 but nevertheless cannot achieve a further elevation in Bmp/Smad target gene expression when Tmprss6 is absent. Hfe might, for example, promote Bmp/Smad signaling by Hjv (B) or promote Bmp/Smad signaling at a point functionally downstream of Tmprss6 (C).

Based on available data, however, we cannot exclude the possibility that Hfe modulates Bmp/Smad signaling through an ancillary mechanism that does not require the action of Tmprss6 but is nevertheless unable to further induce the expression of Bmp/Smad target genes when Tmprss6 is absent. For example, Hfe might promote hepcidin expression by stabilizing Hjv on the plasma membrane, but such stabilization might be unnecessary in the absence of Tmprss6-mediated cleavage of Hjv. Alternatively, Hfe might modulate Bmp/Smad signaling functionally downstream from Tmprss6, but in the absence of Tmprss6, signaling through the Bmp/Smad pathway might already be occurring at the maximum rate, so that Hfe is ineffective at inducing a further increase in Bmp/Smad signaling.

From a therapeutic standpoint, our data suggest an additional target for intervention in HFE-HH. Reduction of iron stores by phlebotomy remains the standard of care in HFE-HH. However, one alternative therapeutic strategy is to prevent the absorption of excess dietary iron in these patients. Two recent studies examined whether long-term administration of agents designed to raise circulating hepcidin levels could reduce systemic iron loading in Hfe−/− mice. Intraperitoneal injection of Hfe−/− mice with supraphysiologic doses of purified recombinant human BMP6 (500 μg/kg twice daily for 10 days starting at 8 weeks of age) produced significant increases in hepatic hepcidin mRNA and significant reductions in SI and TS, but failed to produce a significant reduction in LIC in this time frame.31 Unfortunately, the effect of long-term BMP6 administration could not be assessed because of the development of intraperitoneal calcifications in the treated Hfe−/− mice, likely reflecting the bone-inducing properties of BMP6. Intraperitoneal injection of Hfe−/− mice with synthetic hepcidin (50 μg every 2 days for 2 months starting a 8 weeks of age) produced a significant reduction (24%) in plasma iron concentration compared with treatment with saline alone, but did not alter hepatic or splenic iron stores.43 It is difficult to compare these published effects of BMP6 and hepcidin administration directly to the effects of genetic disruption of Tmprss6 because in the Hfe−/− mice we studied, Tmprss6 function was deficient since birth. In future studies, alternative genetic approaches, such as inducible gene targeting or siRNA gene knockdown, might be used to determine whether iron loading in Hfe−/− mice can be reduced if Tmprss6 inhibition is initiated at a later age.

Our findings here nevertheless raise the possibility that pharmacologic inhibition of TMPRSS6 activity might prove to be an effective therapy to limit dietary iron absorption in HFE-HH; in fact, 2 small-molecule inhibitors of TMPRSS6 were recently demonstrated in vitro.44 In humans, the expression of TMPRSS6 mRNA appears to be liver specific,45 which might make TMPRSS6 a particularly attractive pharmacologic target. Patients with IRIDA who harbor homozygous TMPRSS6 mutations have not been observed to exhibit any physical or biochemical abnormalities beyond those that can be directly attributed to their iron deficiency,21,23 suggesting that the biologic effects resulting from inhibition of TMPRSS6 activity may be restricted to iron homeostasis. However, the therapeutic use of TMPRSS6 inhibitors in HFE-HH might require tight monitoring to prevent the development of iron deficiency anemia due to overcorrection of the hepcidin defect.

In addition to having implications relevant to the treatment of HFE-HH, our data may also help to explain the variable clinical penetrance observed in this disorder. Patients with HFE-HH, including those who are homozygous for the common C282Y mutation, show wide variations in both the degree of iron loading and the progression to end organ damage, which appears to reflect the influence of both environmental factors and modifier genes that are not yet fully understood.46 Interestingly, several recent genome-wide association studies conducted in healthy human populations have shown that laboratory indicators of systemic iron homeostasis, including SI, TS, Hgb, hematocrit, MCV, and MCH, are significantly associated with single nucleotide polymorphisms in the TMPRSS6 gene.47-50 One of the TMPRSS6 nucleotide polymorphisms identified in these studies, rs855791, results in a valine-to-alanine substitution at position 736 of the TMPRSS6 proteolytic domain, raising the intriguing possibility that this particular nucleotide polymorphisms might be a causal variant. In light of these results obtained in human populations, our findings in Hfe−/− mice raise the possibility that natural genetic variations in the human ortholog TMPRSS6 might contribute to the variable clinical penetrance of HFE-HH. Our data presented here may motivate the design of future studies to examine the extent to which common variation in TMPRSS6 modifies the clinical penetrance of HFE-HH and the ability of pharmacologic inhibition of TMPRSS6 to attenuate iron loading in this disorder.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jackie Lim and Paul Schmidt for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Cooley's Anemia Foundation Research Fellowship (to K.E.F.) and by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K08 DK084204 to K.E.F. and R01 DK066373 to N.C.A.).

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: K.E.F. designed and performed research, analyzed results, and wrote the paper; R.L.W. performed research, analyzed results, and assisted with preparation of the paper; and N.C.A. designed research and assisted with writing the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Karin E. Finberg, Duke University Medical Center, Department of Pathology, Box 3712, Durham, NC 27710; email: karin.finberg@duke.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal