In this issue of Blood, Straus and colleagues on behalf of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) present the outcome of a phase 2 trial of doxorubicin, vinblastine, and gemcitabine for patients with early-stage, nonbulky, Hodgkin lymphoma.1 The complete response rate and progression-free survival were inferior to comparable series, emphasizing the challenges of improving outcome in this highly curable population.

The treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma, particularly in early stage, has been one of the true victories in the war on cancer. The current standard therapeutic approach of 2-4 cycles of doxorudicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacardazine (ABVD) (depending on clinical risk factors) followed by 20-30 Gy of involved field radiation therapy definitively cures > 90% of patients.2 Even for patients with adverse clinical prognostic features, 5-year progression-free survival approaches 90% with this combined modality approach.

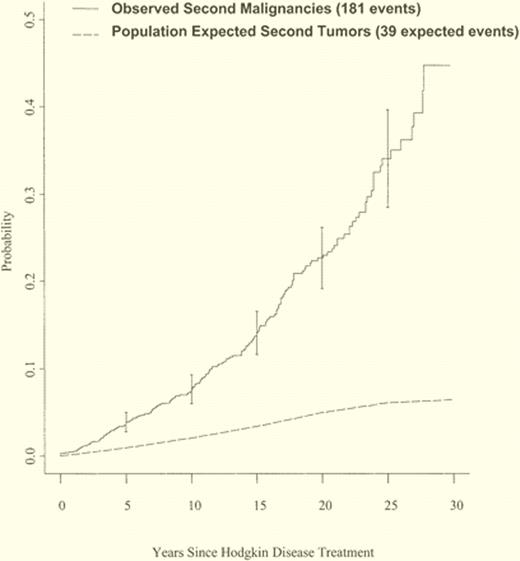

Unfortunately, these cures have come with a cost. In an analysis of > 1000 patients under age 50 treated with radiation (with or without chemotherapy) between 1967 and 1997 for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, the relative risk of mortality from all causes, causes other than Hodgkin disease, second tumors, and cardiac disease remains significantly elevated > 20 years after treatment, even for patients in the most favorable prognostic groups.3 Other analyses have demonstrated that the excess risk of second malignancy after cure for Hodgkin disease continues to be increased after 20 years, and there does not appear to be a plateau through at least 25 years (see figure).4 Patients exposed to large radiation fields are at the highest risk of lethal second malignancies, including lung cancer, breast cancer, and acute leukemia.

Cumulative incidence of observed second tumors in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma and expected tumors in a matched population. Adapted from Ng et al.4

Cumulative incidence of observed second tumors in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma and expected tumors in a matched population. Adapted from Ng et al.4

Therefore, current research efforts are focusing on minimizing toxicity of therapy to improve ultimate outcome of patients with early-stage, favorable, Hodgkin lymphoma. These efforts include minimizing radiation fields and dose with involved node (rather than involved field) radiation,5 using a response-adapted approach incorporating fluorodeoxyglucose position emission tomography (FDG-PET) imaging to eliminate radiation therapy in patients obtaining an early, complete response to chemotherapy,6 and minimizing exposure to chemotherapy drugs.7

In the current study by CALGB, 99 evaluable patients were treated with a novel chemotherapy combination (AVG: doxorubicin, vinblastine, gemcitabine) for 6 cycles with no radiation therapy. Similar to the experience with other gemcitabine-containing combinations in Hodgkin lymphoma,8 pulmonary toxicity was noted, and delays of chemotherapy because of cytopenias were required in 70% of patients. FDG-PET imaging during and after therapy was highly predictive of outcome; 2-year progression-free survival for patients who were PET negative after 2 cycles of therapy was 88%, compared with only 54% for patients who had PET positivity after 2 cycles of therapy. For the entire group of patients, the 3-year progression-free survival was a disappointing 77%, a result inferior to 10-year follow-up of patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma treated with escalated bleomycin, etopside, doxorudicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procardazine, and prednisone (BEACOPP) chemotherapy.9

What went wrong with this trial, and how can we improve outcome for patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma in the future? First, this phase 2 trial attempted to evaluate a novel chemotherapy combination and eliminate radiation therapy at the same time. The toxicity and low complete response rate of the AVG chemotherapy combination renders it impossible to evaluate the radiation question. Indeed, the low relapse rate in PET negative patients after 6 cycles of AVG suggests it is possible to eliminate radiation therapy in a substantial subset of patients without compromising short-term outcome. Other studies attempting to eliminate radiation therapy with an inadequate chemotherapy regimen such as epirudicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and prednisone (EBVP) have had similar disappointing results.

More importantly though, I believe we need a new paradigm to evaluate the total impact of therapy in early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. Although this trial was designed to minimize late effects of treatment, clearly the appropriate rationale in this disease, the primary end point of the study by Straus and colleagues was complete response rate. Only with 10 years or more of follow-up can we really determine the total impact of therapy on a young patient with Hodgkin lymphoma. Analyses need to include quality of life, burden of second malignancies, cardiac and pulmonary damage, and ultimately, overall survival. It is likely we will need to compromise upfront cure to some degree to minimize these late, morbid risks. Thus, the entire clinical trial infrastructure must change to accommodate these types of questions. We need better tools to evaluate quality of life in these patients, and novel, creative end points that integrate cure of Hodgkin lymphoma with the effects of treatment. These tools need to have the same rigor as our current clinical and imaging response criteria. Adequate funding is necessary to follow patients through years of remission for late effects to emerge. Without such trial designs, and patience on the part of investigators, we are setting ourselves up for failure, as recently has occurred in a large, ambitious response-adapted trial in early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma closed prematurely by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) for a 1-year end point.10

Currently, the CALGB is taking a more incremental approach using standard ABVD as the chemotherapy platform for early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, escalating treatment in patients who are PET positive after 2 cycles of therapy while eliminating radiation in patients who are PET negative after 2 cycles of therapy. This is a most reasonable concept, but we will need patience and integration of the aforementioned analyses to truly determine the impact of this approach on our patients.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author is a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and is supported in part by the University of Rochester SPORE in lymphoma. ■

REFERENCES

National Institutes of Health