Abstract

The granule enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO) plays an important role in neutrophil antimicrobial responses. However, the severity of immunodeficiency in patients carrying mutations in MPO is variable. Serious microbial infections, especially with Candida species, have been observed in a subset of completely MPO-deficient patients. Here we show that neutrophils from donors who are completely deficient in MPO fail to form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), indicating that MPO is required for NET formation. In contrast, neutrophils from partially MPO-deficient donors make NETs, and pharmacological inhibition of MPO only delays and reduces NET formation. Extracellular products of MPO do not rescue NET formation, suggesting that MPO acts cell-autonomously. Finally, NET-dependent inhibition of Candida albicans growth is compromised in MPO-deficient neutrophils. The inability to form NETs may contribute in part to the host defense defects observed in completely MPO-deficient individuals.

Introduction

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is one of the most abundant proteins in neutrophils, accounting for 5% of the dry weight of the cell.1 Stored in the azurophilic granules and released when neutrophils are stimulated, MPO catalyzes the oxidation of chloride and other halide ions in the presence of hydrogen peroxide2,3 to generate hypochlorous acid and other highly reactive products that mediate efficient antimicrobial action.4,5

Several inherited mutations and deletions in the gene encoding MPO result in decreased enzyme production and activity.6,7 Using automated hematological devices, clinicians can distinguish between partial and complete MPO deficiencies.8 MPO deficiency is reported to have an incidence of 1 in 2000-4000 in the United States and Europe and 1 in 55 000 in Japan.9-13 Candida infections are common in MPO-deficient patients, especially in those that also develop diabetes.9,14-18 Occasionally, serious infectious or inflammatory complications have been observed in completely MPO-deficient patients as well.8 Consistently, MPO knockout mice are susceptible to particular bacterial and fungal infections.19

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are part of the neutrophil response to microbes. Activated neutrophils die and release these structures composed of decondensed chromatin and antimicrobial proteins20,21 that trap and inhibit a broad range of microbes.22 Little is known about the molecular mechanism that regulates NET formation, making the antimicrobial role of NETs in vivo difficult to assess.

Interestingly, neutrophils from chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) patients fail to make NETs.20 CGD is caused by mutations that disrupt the ability of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase to generate superoxide, which dismutates to hydrogen peroxide, the substrate of MPO. CGD patients are prone to recurrent and severe infections, as well as to persistent inflammation that can occur independently of infection.23-25 NET formation by CGD neutrophils is restored by the addition of exogenous hydrogen peroxide, indicating that reactive oxygen species are required for NET formation.20 Here we show that MPO is necessary for making NETs and suggest that defective NET formation may undermine host defense in patients lacking MPO.

Methods

Donor consent

All donors gave consent to blood drawing in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and to functional and genetic analysis. Samples were collected with approval from the ethical committees at each institution.

Neutrophil isolation

Neutrophils were isolated by centrifuging heparinized venous blood over Histopaque 1119 (Sigma-Aldrich) and subsequently over a discontinuous Percoll (Amersham Biosciences) gradient as described previously.20 Cells were stored in Hank buffered salt solution (-) or Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (-), without calcium or magnesium, before experiments.

NET formation and visualization

Neutrophils (5 × 104) were seeded per well in 24-well tissue culture plates, in Hanks buffered salt solution (+), with calcium and magnesium, or RPMI 1640. For donors 1-4, but not 5 and 6, media was supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, or 10% human plasma for Candida albicans stimulation experiments. Cells were stimulated with 100nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma), or with yeast-form C albicans opsonized in 100% human plasma at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. For transwell experiments, neutrophils from a control donor were seeded in 0.4-μm transwell inserts (Falcon) placed into tissue culture wells containing MPO-deficient neutrophils. For cell co-incubation experiments, neutrophils from a healthy and a completely MPO-deficient donor were differentially stained using 1μM MitoTracker Deep Red FM or MitoTracker Green FM (Molecular Probes) according to manufacturer's directions. After staining, the cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio, and 5 × 105 cells were seeded per well. Where applicable, cells were pretreated with 500μM aminobenzoic acid hydrazide (ABAH) for 1 hour. To visualize NETs, cells were either fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or left unfixed, and Sytox Green (1:15 000; Invitrogen) or Hoechst (1:60 000; Invitrogen) was added to medium.

Generation of histamine chloramines

Histamine monochloramine and histamine dichloramine were generated using an in vitro system consisting of MPO, H2O2, and histamine, as described.26 After 30 minutes at 37°C, catalase (1000 U/mL) was added to consume any remaining H2O2. Negatively charged SP Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were used to precipitate the positively charged MPO. Chloramines were prepared freshly and stored on ice in the dark for a maximum of 15 minutes before use.

Immunofluorescence staining

Neutrophils seeded on glass coverslips were fixed 4 hours after activation, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, then blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin. Samples were stained with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-neutrophil elastase (1:500; in-house) and histone H2A/H2B/DNA complex (PR1-3, 1:500; kindly provided by M. Monestier, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Cy2 and Cy3 were used.

NET quantitation

The area of Sytox staining for each cell was measured from micrographs using ImageJ software. All fixed cells were labeled by Sytox. In unfixed samples, only dead cells were Sytox-positive. The distribution of the number of cells across the range of nuclear area was obtained using the frequency function in Microsoft Excel. The Sytox-positive counts were divided by the total number of cells, determined from corresponding phase contrast images, and plotted as the percentage of Sytox-positive cells within each area range.

NET-mediated growth inhibition of C albicans

Neutrophils (5 × 105) were seeded per well in 24-well tissue culture plates, in RPMI 1640, then activated with glucose oxidase (100 mU/mL)20 to form NETs. After 2 hours, samples were either left untreated or were treated with cytochalasin D (10 μg/mL) for 30 minutes to prevent phagocytosis by cells that had not formed NETs. Yeast form C albicans were added at an MOI of 0.01 and centrifuged onto the NETs. At 10 hours after infection, fungal growth was measured by adding 0.5 mg/mL XTT (Invitrogen) and 40 μg/mL coenzyme Q0 (Sigma-Aldrich) and monitoring the absorbance at 450 nm.

Statistical analysis

Raw measurements were analyzed in Graph Pad Prism 5 software using the Mann-Whitney test (2 samples) or the Kruskall-Wallis analysis of variance and Dunn multiple comparison test (3 or more samples).

Microscopy

Live cells stained with Sytox Green were imaged using a Leica Leitz DM IRB inverted epifluorescence microscope with Leica 10×/0.22 and 20×/0.40 objectives, at 25°C in RPMI. Images were captured using a Spot InSight camera from Diagnostic Instruments and Improvision OpenLab 4.0.1 software. Fixed cells were imaged using a Leica DM R upright epifluorescence microscope with Leica 10×/0.3, 20×/0.5, and 40×/0.75 objectives, at 25°C in Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich). For immunofluorescence, secondary antibodies were conjugated to Cy2 and Cy3. For cell mixing experiments, MitoTracker Green FM, MitoTracker Deep Red FM, and Hoechst were used. Images were captured using a Nikon DXM1200F camera and Nikon ACT-1 software. Images were processed using Adobe PhotoShop CS3.

Results

Characterization of MPO-deficient donors

We tested NET formation by neutrophils isolated from 6 unrelated MPO-deficient donors that reside in Europe and the United States. The donors had different mutations and deletions in the MPO locus (Table 1). We separated the donors into a completely deficient group (CD) and a partially deficient group (PD) on the basis of MPO protein amount and enzymatic activity.

MPO-deficient donors

| Donor . | Country . | Genotype . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Germany | c.2031-2A>C/c.2031-2A>C | 38 |

| 2 | USA | c.2031-2A>C/c.2031-2A>C | |

| 3 | France | c.1555-1568del14, p.M519PfsX21/c.1907C>T, p.T636M and c.2031-2A>C | 27 |

| 4 | France | c.995C>T, p.A332V/c. 2031-2A>C | 27 |

| 5 | Luxembourg | c.752T>C, p.M251T/c.1705C>T, p.R569W | |

| 6 | USA | c.929T>C, p.M251T/g.8089C>T, pR569W | 39 |

| Donor . | Country . | Genotype . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Germany | c.2031-2A>C/c.2031-2A>C | 38 |

| 2 | USA | c.2031-2A>C/c.2031-2A>C | |

| 3 | France | c.1555-1568del14, p.M519PfsX21/c.1907C>T, p.T636M and c.2031-2A>C | 27 |

| 4 | France | c.995C>T, p.A332V/c. 2031-2A>C | 27 |

| 5 | Luxembourg | c.752T>C, p.M251T/c.1705C>T, p.R569W | |

| 6 | USA | c.929T>C, p.M251T/g.8089C>T, pR569W | 39 |

Nomenclature for genotypes is according to den Dunnen and Antonarakis.40 The c.2031-2A>C splice mutation in donors 1-3, and the frameshift deletion in donor 3 consistently generate null alleles, whereas the missense mutations in donors 4-6 allow for residual MPO activity.

The heavy chain of mature MPO was undetectable in CD neutrophil lysates (donors 1-3; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article27 ), and MPO activity was absent (supplemental Figure 227 ). In contrast, the PD donors (donors 4-6) displayed only a decrease in MPO protein expression (supplemental Figure 127 ; the MPO deficiency of donor 5 was confirmed by staining of cell smears with o-dianisidine modified according to Fujinami et al28 ) and exhibited significant residual MPO activity (supplemental Figure 227 ). All donors displayed NADPH oxidase activity (supplemental Figure 227 ), indicating that they do not suffer from CGD.

Although the donors were healthy at the time of sampling, 2 CD donors have a history of severe or repeated infections. Donor 1 was hospitalized for 4 months due to severe pneumonia and required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Furthermore, over the course of infection, donor 1 developed cerebral lesions, and septic abscesses were suspected. At different points in time, cultures from bronchial fluid yielded Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida krusei, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Donor 2 had 2 incidents of oral candidiasis and suffers from other medical conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic asthma, stable pulmonary nodules, and psoriasis. Donor 3 and all 3 PD donors are healthy.

MPO is required for NET formation

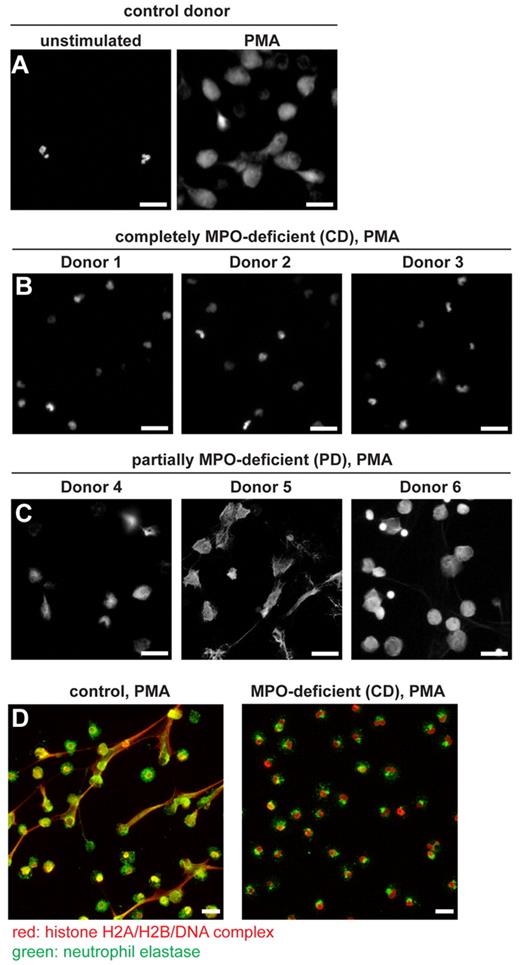

Because NADPH oxidase is required for NET formation, and its absence could be compensated by addition of exogenous hydrogen peroxide,20 we asked whether MPO is also required in this process. Control and MPO-deficient neutrophils were stimulated with PMA, an activator of protein kinase C and a potent NET stimulus. NETs were visualized by fixing cells and staining with a DNA dye. After 4 hours of PMA stimulation, neutrophils from healthy donors released NETs (Figure 1A right panel), defined as decondensed chromatin that stained positively for neutrophil elastase and the histone H2A/H2B/DNA complex21 (Figure 1D left panel). Neutrophils from PD donors also made NETs (Figure 1C), while cells from CD donors did not form NETs (Figure 1B,D right panel). The nuclei of naive cells remained lobulated and condensed (Figure 1A left panel).

MPO is required for NET formation. Neutrophils were activated with PMA for 4-6 hours to stimulate NET formation, then stained with the DNA dye Sytox green (A-C) or (D) immunostained with antibodies against the histone H2A/H2B/DNA complex (red) and neutrophil elastase (green). (A) Neutrophils from a control donor formed NETs after PMA stimulation, and naive cells had small, condensed nuclei. (B) Neutrophils from completely MPO-deficient donors did not form NETs, as indicated by their condensed nuclei similar to those of unstimulated neutrophils. (C) Partially MPO-deficient neutrophils made NETs. (D) Extracellular DNA released from control neutrophils stained with antibodies against chromatin and neutrophil elastase, 2 known NET components. In completely MPO-deficient neutrophils, as in naive neutrophils,20 neutrophil elastase was localized in granules and chromatin remained condensed. Experiments with CD neutrophils were repeated at least 6 times with 3 independent, unrelated donors. Experiments with PD neutrophils were repeated at least 3 times with 3 independent, unrelated donors. Scale bar, 25 μm.

MPO is required for NET formation. Neutrophils were activated with PMA for 4-6 hours to stimulate NET formation, then stained with the DNA dye Sytox green (A-C) or (D) immunostained with antibodies against the histone H2A/H2B/DNA complex (red) and neutrophil elastase (green). (A) Neutrophils from a control donor formed NETs after PMA stimulation, and naive cells had small, condensed nuclei. (B) Neutrophils from completely MPO-deficient donors did not form NETs, as indicated by their condensed nuclei similar to those of unstimulated neutrophils. (C) Partially MPO-deficient neutrophils made NETs. (D) Extracellular DNA released from control neutrophils stained with antibodies against chromatin and neutrophil elastase, 2 known NET components. In completely MPO-deficient neutrophils, as in naive neutrophils,20 neutrophil elastase was localized in granules and chromatin remained condensed. Experiments with CD neutrophils were repeated at least 6 times with 3 independent, unrelated donors. Experiments with PD neutrophils were repeated at least 3 times with 3 independent, unrelated donors. Scale bar, 25 μm.

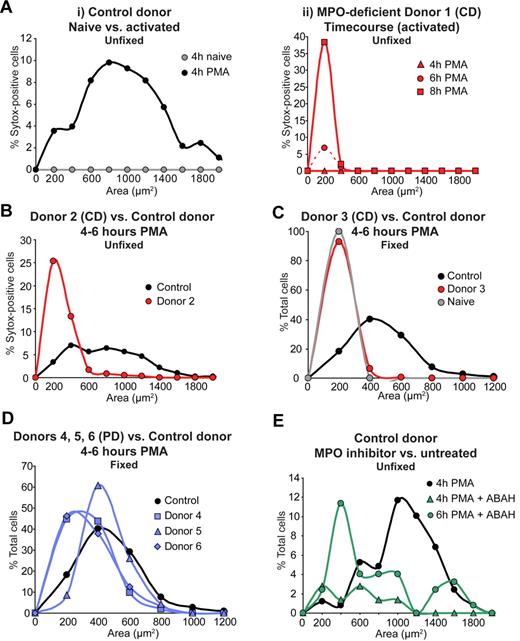

To rule out the possibility that NET formation in MPO-deficient neutrophils is delayed, we quantitated NET formation in CD neutrophils over an 8-hour time course after PMA activation. In culture, neutrophils die within this time frame.29 To distinguish NET-cell death from apoptosis or necrosis, we stained the unfixed cells with Sytox, a cell-impermeable DNA dye, and measured the size of the released nuclear contents from micrographs using software-assisted techniques. Naive neutrophils were still alive after 4 hours and did not stain with Sytox (Figure 2Ai). Neutrophils from a healthy donor efficiently formed NETs by 4 hours after PMA activation, as indicated by the significant increase in nuclear area (Figure 2Ai). However, neutrophils from CD donor 1 did not form NETs, even after 8 hours of PMA stimulation; instead, many cells died but displayed condensed nuclei (Figure 2Aii).

Quantitation of NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils. Nuclear areas of neutrophils stimulated with PMA as in Figure 1 are plotted against the percentage of Sytox-positive cells corresponding to a given nuclear area range. Cells were unfixed (A-B,E) or fixed with paraformaldehyde (C-D) before Sytox staining. (Ai) By 4 hours after PMA stimulation, neutrophils from a control donor made NETs, indicated by the broad range of nuclear areas. Naive cells were still alive and did not stain with Sytox. (Aii) In contrast, neutrophils from a completely MPO-deficient donor did not form NETs. Instead, the cells died by 6 to 8 hours after PMA stimulation, but their nuclei remained small. (B-C) Neutrophils from 2 other completely MPO-deficient donors did not make NETs after 4-6 hours of PMA stimulation. (D) Neutrophils from 3 partially MPO-deficient donors made NETs. (E) Neutrophils from a control donor pretreated with the MPO inhibitor ABAH displayed a 2-hour delay and significant decrease in NET formation, reaching peak nuclear areas at 6 hours instead of 4 hours after PMA stimulation. Color scheme: gray, naive cells; black, control or untreated cells; red, completely MPO-deficient cells; blue, partially MPO-deficient cells; green, ABAH-treated cells. Statistical analysis: ***P < .0001; n.s., differences not significant. (A) Control versus donor 1 (6 hours)***; control versus donor 1 (8 hours)***; donor 1 (6 hours) versus donor 1 (8 hours), n.s. (B) Control versus donor 2***. (C) Control versus naive***; control versus donor 3***; donor 3 versus naïve, n.s. (D) Control versus donor 4***; control versus donor 5, n.s.; control versus donor 6***. (E) 4-hour PMA versus 4-hour PMA plus ABAH***; 4-hour PMA versus 6-hour PMA plus ABAH***; 4-hour PMA plus ABAH versus 6-hour PMA plus ABAH, n.s. For each sample, 100-500 cells were evaluated.

Quantitation of NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils. Nuclear areas of neutrophils stimulated with PMA as in Figure 1 are plotted against the percentage of Sytox-positive cells corresponding to a given nuclear area range. Cells were unfixed (A-B,E) or fixed with paraformaldehyde (C-D) before Sytox staining. (Ai) By 4 hours after PMA stimulation, neutrophils from a control donor made NETs, indicated by the broad range of nuclear areas. Naive cells were still alive and did not stain with Sytox. (Aii) In contrast, neutrophils from a completely MPO-deficient donor did not form NETs. Instead, the cells died by 6 to 8 hours after PMA stimulation, but their nuclei remained small. (B-C) Neutrophils from 2 other completely MPO-deficient donors did not make NETs after 4-6 hours of PMA stimulation. (D) Neutrophils from 3 partially MPO-deficient donors made NETs. (E) Neutrophils from a control donor pretreated with the MPO inhibitor ABAH displayed a 2-hour delay and significant decrease in NET formation, reaching peak nuclear areas at 6 hours instead of 4 hours after PMA stimulation. Color scheme: gray, naive cells; black, control or untreated cells; red, completely MPO-deficient cells; blue, partially MPO-deficient cells; green, ABAH-treated cells. Statistical analysis: ***P < .0001; n.s., differences not significant. (A) Control versus donor 1 (6 hours)***; control versus donor 1 (8 hours)***; donor 1 (6 hours) versus donor 1 (8 hours), n.s. (B) Control versus donor 2***. (C) Control versus naive***; control versus donor 3***; donor 3 versus naïve, n.s. (D) Control versus donor 4***; control versus donor 5, n.s.; control versus donor 6***. (E) 4-hour PMA versus 4-hour PMA plus ABAH***; 4-hour PMA versus 6-hour PMA plus ABAH***; 4-hour PMA plus ABAH versus 6-hour PMA plus ABAH, n.s. For each sample, 100-500 cells were evaluated.

Neutrophils from 2 other CD donors (donors 2 and 3) also failed to make NETs (Figure 2B-C). Cells from the PD donors 4 and 6 displayed intermediate nuclear areas, and cells from donor 5 had nuclear areas similar to the healthy control donor (Figure 2D).

To complement our study of MPO-deficient neutrophils, we treated normal neutrophils with the MPO inhibitor ABAH. By 4 hours after PMA stimulation, untreated neutrophils formed NETs efficiently, but only a small proportion of ABAH-treated neutrophils formed NETs (Figure 2E). By 6 hours, more ABAH-treated neutrophils formed NETs (Figure 2E). However, even after this 2-hour delay, most ABAH-treated neutrophils did not form NETs, and the mean nuclear area was significantly lower than untreated cells (Figure 2E). Because ABAH did not completely abrogate MPO activity30 (supplemental Figure 3), low levels of MPO activity appear sufficient to support NET formation by some cells. These data complement our finding that partially MPO-deficient neutrophils formed NETs.

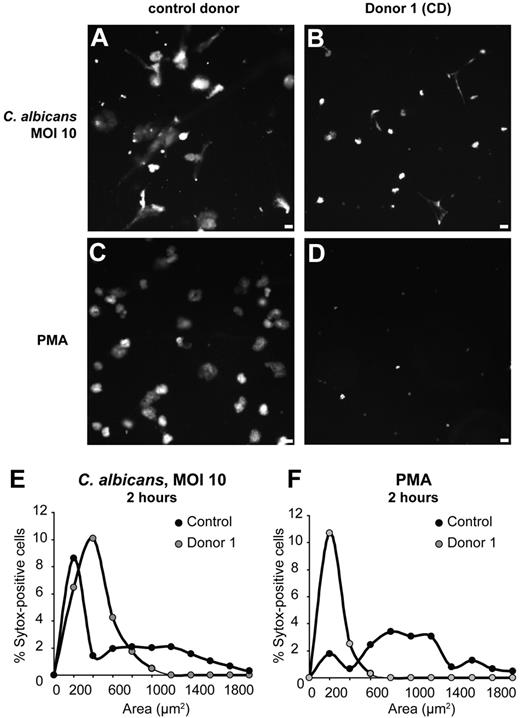

To assess NET formation in response to a physiological stimulus, we incubated control and completely MPO-deficient (donor 1) neutrophils with opsonized yeast form C albicans. After 2 hours, neutrophils from the control donor made robust NETs in response to the yeast (Figure 3A,E) and to PMA (Figure 3C,F). In contrast, MPO-deficient neutrophils did not make NETs in response to yeast (Figure 3B,E) or PMA (Figure 3D,F). Instead, many cells died with condensed nuclei, while some condensed DNA appeared stringy, likely due to cell damage by fungal growth. Taken together, these data clearly show that MPO is required for NET formation.

NET formation in response to C albicans is impaired in MPO-deficient neutrophils. Neutrophils were co-incubated with the yeast form of C albicans at an MOI of 10, or activated with PMA, for 2 hours, and DNA was stained with Sytox. (A-D) Images of Sytox fluorescence. (E-F) Quantitation of nuclear areas. Neutrophils from a healthy donor formed NETs upon stimulation with C albicans (A,E) and PMA (C,F), but neutrophils from a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) did not form NETs in response to C albicans (B,E) or PMA (D,F). Scale bar, 25 μm.

NET formation in response to C albicans is impaired in MPO-deficient neutrophils. Neutrophils were co-incubated with the yeast form of C albicans at an MOI of 10, or activated with PMA, for 2 hours, and DNA was stained with Sytox. (A-D) Images of Sytox fluorescence. (E-F) Quantitation of nuclear areas. Neutrophils from a healthy donor formed NETs upon stimulation with C albicans (A,E) and PMA (C,F), but neutrophils from a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) did not form NETs in response to C albicans (B,E) or PMA (D,F). Scale bar, 25 μm.

MPO acts cell autonomously to promote NET formation

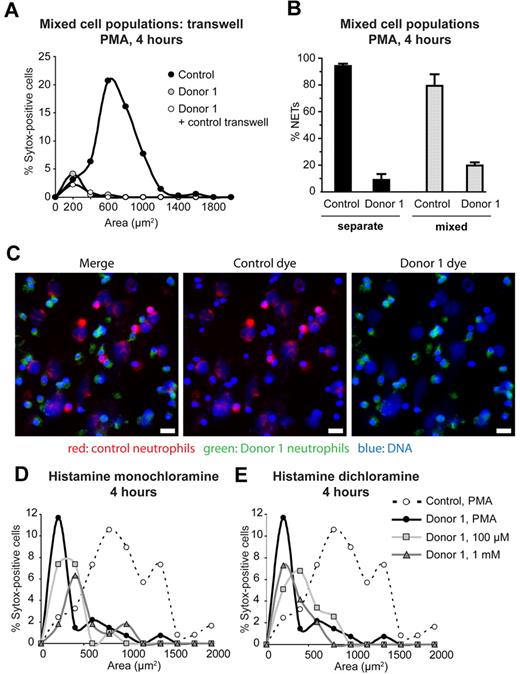

To examine whether MPO acts cell autonomously during NET formation, we attempted to use extracellular products of MPO to rescue NET formation in MPO-deficient neutrophils. First, we incubated completely MPO-deficient neutrophils (donor 1) with neutrophils from a healthy donor separated by a transwell system and assessed NET formation upon PMA stimulation. The presence of cells with functional MPO in the culture did not increase NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils (Figure 4A).

NET formation by MPO-deficient cells is not rescued by extracellular products of MPO. (A) Neutrophils from a healthy and a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) were incubated either separately or co-incubated in a transwell system. Upon PMA activation, control neutrophils formed NETs. MPO-deficient neutrophils did not form NETs, even in the presence of control cells on a transwell insert. (B) Neutrophils from a healthy and a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) were either incubated separately or mixed at a 1:1 ratio and stimulated with PMA. Before mixing, cells were differentially stained using MitoTracker Green and Deep Red dyes to distinguish the 2 populations. NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils was not significantly increased in the presence of control neutrophils. (C) A representative image of the mixed cell culture from panel B. Red, MitoTracker Deep Red–stained neutrophils from a healthy donor; green, MitoTracker Green–stained neutrophils from donor 1 (CD); blue, DNA (Hoechst). Left panel, merge of all 3 colors; middle panel, merge of red and blue channels; right panel, merge of green and blue channels. Scale bar, 25 μm. (D-E) Histamine monochloramine and histamine dichloramine were generated using an in vitro enzymatic system, then applied to neutrophils from a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) at the indicated concentrations. Neither chloramine tested rescued NET formation by the MPO-deficient cells. Statistical analysis: ***P < .0001; *P = .01-05; n.s., differences not significant. (A) Control versus donor 1***; control versus donor 1 plus control transwell***; donor 1 versus donor 1 plus control transwell, n.s. (D) Control, PMA versus donor 1, PMA***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM ***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM*; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM, n.s.; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s.; donor 1, 100μM versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s. (E) Control, PMA versus donor 1, PMA***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM***; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM, n.s.; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s.; donor 1, 100μM versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s. For each sample, 100-500 cells were evaluated.

NET formation by MPO-deficient cells is not rescued by extracellular products of MPO. (A) Neutrophils from a healthy and a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) were incubated either separately or co-incubated in a transwell system. Upon PMA activation, control neutrophils formed NETs. MPO-deficient neutrophils did not form NETs, even in the presence of control cells on a transwell insert. (B) Neutrophils from a healthy and a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) were either incubated separately or mixed at a 1:1 ratio and stimulated with PMA. Before mixing, cells were differentially stained using MitoTracker Green and Deep Red dyes to distinguish the 2 populations. NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils was not significantly increased in the presence of control neutrophils. (C) A representative image of the mixed cell culture from panel B. Red, MitoTracker Deep Red–stained neutrophils from a healthy donor; green, MitoTracker Green–stained neutrophils from donor 1 (CD); blue, DNA (Hoechst). Left panel, merge of all 3 colors; middle panel, merge of red and blue channels; right panel, merge of green and blue channels. Scale bar, 25 μm. (D-E) Histamine monochloramine and histamine dichloramine were generated using an in vitro enzymatic system, then applied to neutrophils from a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) at the indicated concentrations. Neither chloramine tested rescued NET formation by the MPO-deficient cells. Statistical analysis: ***P < .0001; *P = .01-05; n.s., differences not significant. (A) Control versus donor 1***; control versus donor 1 plus control transwell***; donor 1 versus donor 1 plus control transwell, n.s. (D) Control, PMA versus donor 1, PMA***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM ***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM*; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM, n.s.; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s.; donor 1, 100μM versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s. (E) Control, PMA versus donor 1, PMA***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM***; control, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM***; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 100μM, n.s.; donor 1, PMA versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s.; donor 1, 100μM versus donor 1, 1mM, n.s. For each sample, 100-500 cells were evaluated.

In addition, we incubated differentially stained MPO-deficient (donor 1) and healthy neutrophils either separately or mixed together in a 1:1 ratio. When incubated separately, approximately 9% of the MPO-deficient neutrophils formed NETs, compared with 95% of control neutrophils (Figure 4B). In the mixed culture, NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils increased only slightly, to 20%, compared with 80% NET formation by control neutrophils (Figure 4B). This slight increase in NET formation could be due to factors released by neighboring healthy neutrophils that made NETs. A representative image of the mixed cell culture is shown in Figure 4C. These results suggest that the products of MPO that induce NETs have a short range of action and that MPO acts cell-autonomously during NET formation.

In addition to the short-lived hypohalous acids, MPO can generate chloramines, which are longer-lived compounds that can affect distant cells.5 We asked whether histamine chloramines could rescue NET formation by MPO-deficient cells. Using an in vitro system consisting of MPO, H2O2, and histamine, we generated histamine monochloramine and histamine dichloramine26 and added these compounds to MPO-deficient neutrophils (donor 1). Neither of the histamines tested rescued NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils (Figure 4D-E), again arguing for a cell-autonomous role for MPO in NET formation.

NET-dependent inhibition of C albicans growth is compromised in MPO-deficient neutrophils

Although most MPO-deficient individuals are healthy, some suffer from recurrent or severe infections, especially with Candida species.14-16,18 In addition, NETs have been suggested to be important in host defense against fungal pathogens, particularly hyphal forms that are not efficiently phagocytosed.31-34 We tested NET-mediated inhibition of C albicans growth in control and MPO-deficient neutrophils. First, control and completely MPO-deficient (donor 1) neutrophils were induced to form NETs. Next, cells were left either untreated or cytochalasin D was added to prevent phagocytic killing by neutrophils that had not formed NETs. Finally, C albicans was added to the cultures. After 10 hours of co-incubation with the neutrophils and/or NETs, fungal growth was measured using a chromogenic metabolic substrate. Control neutrophils efficiently made NETs and restricted fungal growth in the presence and absence of cytochalasin D (Figure 5). In contrast, MPO-deficient neutrophils did not restrict fungal growth in the presence of cytochalasin D (Figure 5). Therefore, NET-mediated fungal growth inhibition was compromised in MPO-deficient neutrophils.

NET-dependent inhibition of C albicans growth is compromised in MPO-deficient neutrophils. Neutrophils from a healthy donor and a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) were stimulated to make NETs using glucose oxidase for 2 hours or were left unstimulated. After NET formation, cells were left untreated or cytochalasin D was added to prevent phagocytic killing by neutrophils that had not made NETs. The yeast form of C albicans was added to the cells, and fungal growth was measured after 10 hours using XTT, a chromogenic metabolic substrate. Measurements were normalized to growth of C albicans in the absence of neutrophils. Control neutrophils efficiently made NETs and restricted fungal growth both in the presence and in the absence of cytochalasin D. MPO-deficient neutrophils did not restrict fungal growth in the presence of cytochalasin D.

NET-dependent inhibition of C albicans growth is compromised in MPO-deficient neutrophils. Neutrophils from a healthy donor and a completely MPO-deficient donor (donor 1) were stimulated to make NETs using glucose oxidase for 2 hours or were left unstimulated. After NET formation, cells were left untreated or cytochalasin D was added to prevent phagocytic killing by neutrophils that had not made NETs. The yeast form of C albicans was added to the cells, and fungal growth was measured after 10 hours using XTT, a chromogenic metabolic substrate. Measurements were normalized to growth of C albicans in the absence of neutrophils. Control neutrophils efficiently made NETs and restricted fungal growth both in the presence and in the absence of cytochalasin D. MPO-deficient neutrophils did not restrict fungal growth in the presence of cytochalasin D.

Discussion

Taken together, our data indicate that MPO is required for NET formation. Partially MPO-deficient neutrophils made NETs, but neutrophils completely deficient in MPO failed to make NETs in response to PMA and C albicans. These data suggest that patients completely deficient in MPO activity may suffer from a more severe immunodeficiency than those with only a partial deficiency. Importantly, the significance of MPO may be understated by grouping partial and complete deficiencies together, given that the prevalence of partial MPO deficiency is higher than that of complete deficiency.

NET formation by MPO-deficient neutrophils could not be rescued by extracellular products of MPO, suggesting that MPO functions cell-autonomously. These results suggest that the process of NET formation requires a high local concentration of the MPO products. Such concentrations may not be reached when the cells are incubated under the described conditions. Alternatively, short-lived products of MPO may need to be generated in the appropriate subcellular compartment. Finally, because ABAH has a weaker phenotype than the complete deficiency, MPO could have an additional function during NET formation that is independent of its enzymatic activity.

Interestingly, under our experimental conditions, MPO-deficient neutrophils controlled C albicans growth as efficiently as healthy neutrophils did, in the absence of cytochalasin D. This is in contrast to previous reports demonstrating a complete lack of C albicans killing by MPO-deficient human neutrophils9,15,18 and uncontrolled Candida infections in mouse models of MPO deficiency.35,36 This different result could be due to several factors that were important to tailor our assay to NET-specific growth inhibition: lower MOI, longer incubation period, and adherent rather than suspension culture conditions. In addition, our assay measures growth inhibition, rather than killing. Although phagocytic killing may be compromised in MPO-deficient neutrophils, under our experimental conditions, residual phagocytosis or other cytochalasin D–dependent antimicrobial mechanisms may have been sufficient to control C albicans growth.

MPO plays an important role in oxygen-dependent killing of microbes in the neutrophil phagosome.5,18 Paradoxically, completely MPO-deficient individuals are generally healthy, despite occasional reports of severe or recurrent infections, especially candidiasis in individuals who also have diabetes mellitus.18 This observation suggests that MPO-deficient individuals are immunocompromised only under specific circumstances. Consistent with this idea, our data point to a NET-specific defect in MPO-deficient neutrophils. Notably, NETs are thought to be important in restricting systemic infection and in host defense against fungal pathogens, especially hyphal forms that may be difficult to phagocytose due to their size.31-34 However, the immune system is equipped with redundant mechanisms, which may also explain why most MPO-deficient individuals are healthy. Hence, NET formation may become critical in infections where other antimicrobial mechanisms are overwhelmed. Future studies may identify conditions where NETs are required for host defense and thus provide insights into the heterogeneity of clinical manifestations associated with MPO deficiency.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Abdul Hakkim and Volker Brinkmann for their technical advice and Dirk Roos for his support of this work.

W.M.N. is funded by a National Institutes of Health R01 AI07958 grant and a Merit Review Grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development and with facilities and resources of the Veterans Administration in Iowa City, IA. V.P. was supported by an EMBO long-term fellowship.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: K.D.M. and T.A.F. designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data; K.D.M. wrote the manuscript; W.M.N., D.R., J.R., I.S., and V.W. arranged blood donation by the MPO-deficient donors, provided facilities for experiments, and, along with T.A.F., contributed useful comments on the manuscript; V.P. assisted with experiments and developed the NET quantitation method; and A.Z. and V.P. directed the study and supervised the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for T.A.F. is Immune Disease Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Correspondence: Arturo Zychlinsky, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Chariteplatz 1, 10117 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: zychlinsky@mpiib-berlin.mpg.de; or Venizelos Papayannopoulos, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Chariteplatz 1, 10117 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: veni@mpiib-berlin.mpg.de.

References

Author notes

V.P. and A.Z. contributed equally to this work.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal