Abstract

The past 5 years have seen an explosion of knowledge about miRNAs and their roles in hematopoiesis, cancer, and other diseases. In myeloid development, there is a growing appreciation for both the importance of particular miRNAs and the unique features of myelopoiesis that are being uncovered by experimental manipulation of miRNAs. Here, we review in detail the roles played by 4 miRNAs, miR-125, miR-146, miR-155, and miR-223 in myeloid development and activation, and correlate these roles with their dysregulation in disease. All 4 miRNAs demonstrate effects on myelopoiesis, and their loss of function or overexpression leads to pathologic phenotypes in the myeloid lineage. We review their functions at distinct points in development, their targets, and the regulatory networks that they are embedded into in the myeloid lineage.

Introduction

Initially discovered by the Ambros and Ruvkun labs in the early 1990s, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as important regulators of gene expression.1,2 In the past several years, significant advances have been made with regards to understanding their integration into molecular networks that control cellular development and function. In the hematopoietic system, several individual miRNAs have emerged as important regulators of physiologic and pathologic myeloid development and function. Here we review important scientific advances in the field and evaluate miRNA biology in the context of myeloid development. Although there are many review articles that survey what is known about miRNA in hematopoiesis and myeloid biology, here we focus in on a few miRNAs as we hope to develop some new paradigms in myeloid biology. We discuss miRNA biogenesis, myeloid differentiation and function, and the roles of 4 important miRNAs in detail: miR-223, miR-146a, miR-155, and miR-125. These miRNAs have been studied intensively in several different model systems, including in murine models in vivo, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of their roles in myeloid biology. We conclude with a synopsis of several other miRNAs that are important in myeloid biology (albeit less intensively studied) and assess future directions.

miRNA biogenesis and action

miRNAs are encoded within exons of unique noncoding genes, or sometimes within introns of protein-coding genes, and are most often transcribed from the genome by RNA polymerase II. Some miRNAs exist as clusters and are encoded on the same primary transcript. The primary transcript (pri-miRNA) is processed by the ribonuclease Drosha/DGCR8 in the nucleus and then transported into the cytoplasm as a pre-miRNA, which contains the miRNA stem-loop structure. For most miRNAs, this serves as a substrate for the endoribonuclease Dicer, which creates a double-stranded short RNA that is unwound and then loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC).3,4 This “classic” description of miRNA biogenesis was true for all known miRNA until mid-2010, when 2 seminal papers reported that Dicer-independent production of miRNAs could occur via the “slicer” RNAse function of Argonaute 2 (Ago2), a component of the RISC.5,6 The biogenesis of miRNAs can be regulated at the transcriptional level by lineage-specific and inflammation-induced transcription factors and at the post-transcriptional level by changes in processing, which can again be induced by inflammatory changes. Hence, production of mature miRNA is regulated as a part of a lineage- or stress-specific transcriptional program, as has been recently reviewed.3

The mature miRNA is loaded onto the RISC, a multiprotein complex that includes members of the Argonaute protein family.7 Once in the RISC, the mature miRNA interacts with a target mRNA via the latter's 3′-untranslated region. Structural, biochemical, and bioinformatics analyses indicate that a 6-nucleotide seed sequence at the 5′ end of the miRNA is important in mediating the interaction with its target.8 In most cases, miRNAs repress their targets, and this change is detectable at the RNA level. It is now thought that this represents the majority of the change induced by miRNAs.9,10 It should be noted that there are scattered reports of miRNAs that interact with their targets in a non–3′-untranslated region-dependent or non–seed-dependent fashion, and miRNAs that cause up-regulation of “targets.”11,12 These studies suggest that there are aspects to miRNA function that remain elusive.

Molecular regulation of myeloid development and activation

The development of myeloid cells from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) involves a step-wise progression of progenitor cells in the bone marrow. Initially described by morphologic features, various myeloid progenitors have been more precisely defined based on colony formation in soft agar and cell surface markers by flow cytometry. A current hierarchical diagram for hematopoietic and myeloid development is shown in Figure 1. The development of the myeloid progenitor cells is linked to the sequential expression of various transcription factors. The earliest transcription factors important in myeloid development, RUNX1 and SCL, also play roles in specification of the HSC during embryogenesis. PU.1, a member of the ETS family of transcription factors, is important for the specification of the common myeloid progenitor from HSCs. Interestingly, dosage of PU.1 is highly important in defining cellular fates in the myeloid lineage, with low doses favoring the development of granulocytes and higher doses favoring the development of monocytes. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα), a basic-region leucine zipper transcription factor, is important for the production of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors from common myeloid progenitors. C/EBPβ is thought to be important in inflammatory myelopoiesis. IFN-γ–responsive factor (IRF)–8 promotes differentiation into monocytes but not granulocytes, whereas GFI-1 is a transcription factor required for granulocyte development. In addition to transcriptional regulators, cell surface cytokine/growth factor receptors and proteins play a role in regulating myeloid development.13

A schematic of hematopoietic development depicting the specific points in differentiation at which the miRNAs discussed in this review are thought to act. Many additional miRNAs have been found by profiling studies to be expressed at these particular stages of differentiation, but these are not shown. MPP indicates multipotent progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor; ETP, early T-cell progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor; MEP, myeloid-erythroid progenitor, Gran, granulocyte; Mon, monocyte; Plat, platelets; and RBCs, red blood cells.

A schematic of hematopoietic development depicting the specific points in differentiation at which the miRNAs discussed in this review are thought to act. Many additional miRNAs have been found by profiling studies to be expressed at these particular stages of differentiation, but these are not shown. MPP indicates multipotent progenitor; LMPP, lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor; ETP, early T-cell progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor; MEP, myeloid-erythroid progenitor, Gran, granulocyte; Mon, monocyte; Plat, platelets; and RBCs, red blood cells.

After maturation in the bone marrow, myeloid cells are subject to activation by inflammatory stimuli. Mediated by pattern recognition receptors or inflammatory cytokines, the activation of myeloid cells in response to pathogens leads to extensive intracellular signaling and transcriptional changes.14,15 One prominent class of pattern recognition receptors are the Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize specific structural motifs found on microbial pathogens called pathogen-associated molecular patterns. The best-described TLR, TLR-4, provides a paradigm for activation of these receptors and subsequent signaling after ligand binding. On binding to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) via its extracellular leucine-rich repeat domain, a complex of proteins is formed on the plasma membrane around the cytoplasmic TIR domain of TLR-4, subsequently recruiting adaptor proteins of the MyD88 family to initiate signal transduction through different IRAK and TRAF family members. Downstream of this complex, MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signal transduction occurs, resulting in the expression of inflammatory cytokines or IFN-inducible genes, respectively. In both cases, activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase takes place, with IRF-3 being activated downstream from TRIF. Interestingly, it is now known that TLRs are also present on HSCs, indicating that these pathways traditionally associated with mature myeloid cells may also regulate developmental changes in early hematopoietic cells during inflammation.16,17

miRNAs in myeloid biology

Initial studies revealed the global importance of miRNAs in hematopoiesis. Dicer deletion in the hematopoietic lineage leads to a marked defect in competitive repopulation assays, and the deletion of Ago2 leads to severe problems with erythroid and B-cell development.18,19 However, the main focus of research in the field has been on examining how individual miRNAs are integrated into various regulatory pathways in myelopoiesis. Many of these were discovered by profiling studies that revealed that a plethora of miRNAs are expressed at various stages of myeloid development.20 After further studies, several of these miRNAs have been functionally confirmed as being important in myeloid biology (Figure 1). miRNAs are induced by transcription factors and other genes involved in myelopoiesis. For example, PU.1 induces expression of miR-223, and NF-κB induces expression of miR-155 and miR-146a (Table 1). miRNAs, in turn, repress the expression of their targets; for example, miR-155 regulates PU.1 and C/EBPβ, thereby changing the transcriptional profile of the cell.21 In this search for targets, global RNA expression profiling followed by correlation with algorithmic target prediction has been fruitful.21 Confirmation of the targets on a case-by-case basis can then be followed by functional analyses of the regulated pathways. Importantly, the dysregulation of these miRNAs has pathologic effects on myeloid development. For a more extensive review of alterations of miRNA in myeloid malignancy, the reader is referred to a recent review on the topic.22 We discuss several miRNAs in the following sections and relate these back to important pathways in myeloid development and activation.

miRNAs induced by various transcription factors in the myeloid lineage and reported targets of the miRNAs

| Transcription factor . | miRNA . | Target . |

|---|---|---|

| GFI1 | Represses miR-196b | HOX genes |

| Represses miR-21 | PDCD4, IL-12p35, JAG1 | |

| PU.1 | Induces miR-223 | MEF2C, NFIA |

| Induces miR-424 | NFIA | |

| RUNX1 | Represses miR-17-92 | BIM, PTEN |

| Represses miR-106a-92 | ||

| C/EBPβ | Induces miR-223 | MEF2C, NFIA |

| C/EBPα | Induces miR-34a | E2F3 |

| NF-κB | Induces miR-146a | TRAF6, IRAK1, STAT1 |

| Induces miR-155 | SHIP1, SOCS1, PU.1, C/EBPβ | |

| Induces miR-9 | NFKB1 | |

| Induces miR-21 | PDCD4, IL-12p35, JAG1 | |

| Induces miR-147 | ||

| PLZF | Represses miR-146a | TRAF6, IRAK1, STAT1 |

| NFIA | Represses miR-223 | MEF2C, NFIA |

| Transcription factor . | miRNA . | Target . |

|---|---|---|

| GFI1 | Represses miR-196b | HOX genes |

| Represses miR-21 | PDCD4, IL-12p35, JAG1 | |

| PU.1 | Induces miR-223 | MEF2C, NFIA |

| Induces miR-424 | NFIA | |

| RUNX1 | Represses miR-17-92 | BIM, PTEN |

| Represses miR-106a-92 | ||

| C/EBPβ | Induces miR-223 | MEF2C, NFIA |

| C/EBPα | Induces miR-34a | E2F3 |

| NF-κB | Induces miR-146a | TRAF6, IRAK1, STAT1 |

| Induces miR-155 | SHIP1, SOCS1, PU.1, C/EBPβ | |

| Induces miR-9 | NFKB1 | |

| Induces miR-21 | PDCD4, IL-12p35, JAG1 | |

| Induces miR-147 | ||

| PLZF | Represses miR-146a | TRAF6, IRAK1, STAT1 |

| NFIA | Represses miR-223 | MEF2C, NFIA |

miR-223

miR-223 was in the first cadre of miRNAs discovered to be highly expressed in myeloid cells in the bone marrow.23 Although that initial study failed to detect an increase in myeloid output from the bone marrow on miR-223 expression, subsequent studies implied a role for miR-223 in myelopoiesis. This miRNA is expressed specifically in cells of the granulocytic lineage and its expression changes during maturation, becoming incrementally higher as granulocytes mature.24 miR-223 expression is lower in a subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), known as acute promyelocytic leukemia, which has a block in differentiation.25 In AML cells, this down-regulation does not appear to be mediated by promoter hypermethylation or by DNA sequence alterations.26 Granulocytic differentiation is restored by constitutive expression of miR-223 in leukemic cells, suggesting a physiologic function for miR-223 in promoting differentiation that is disrupted in disease.27 The mechanisms regulating miR-223 expression have been a chief focus of study, given its apparent importance in granulocytic differentiation.

Expression of miR-223 is regulated by a combination of factors. Initially, a circuit consisting of C/EBPα (a member of the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein family), NFI-A (a transcription factor related to the CCAAT family), and miR-223 was described.28 Here, C/EBPα activates transcription of miR-223, whereas NFI-A represses it. miR-223 itself targets NFI-A, thereby turning off its repressor once it is expressed, forming a positive-autoregulatory circuit (Figure 2). Further work has shown that the situation is probably more complex.29 These more recent analyses indicate that miR-223 expression may be driven by myeloid transcription factors such as PU.1 and C/EBP, similar to many protein-encoding genes involved in granulopoiesis. In leukemia, the AML1-ETO fusion oncoprotein targets the miR-223 promoter for epigenetic silencing, abrogating the ability of myeloid transcription factors to transcribe this miRNA precursor.

Summary of miR-223 regulation and function. miR-223 expression rises incrementally during successive stages of granulocytic differentiation. At the transcriptional level, miR-223 is induced by myeloid-specific factors, such as PU.1 and C/EBPβ, and inhibited by NFI-1. miR-223 inhibits Mef2c and NFI-1, the latter forming a positive feedback circuit.

Summary of miR-223 regulation and function. miR-223 expression rises incrementally during successive stages of granulocytic differentiation. At the transcriptional level, miR-223 is induced by myeloid-specific factors, such as PU.1 and C/EBPβ, and inhibited by NFI-1. miR-223 inhibits Mef2c and NFI-1, the latter forming a positive feedback circuit.

The precise physiologic function of miR-223 remains elusive. In vitro gain- and loss-of-function studies showed that miR-223 promoted granulocytic differentiation in leukemic blasts.27,28 However, studies of a miR-223-knockout mouse showed that these mice had a 2-fold increase in granulocytes.24 These granulocytes were morphologically hypermature and hypersensitive to activation. The mice also had inflammatory lung lesions and demonstrated enhanced tissue destruction after endotoxin challenge. These changes appear to be mediated by Mef2c, which encodes a transcription factor involved in promoting myeloid progenitor differentiation. The miR-223-null phenotype was corrected in mice lacking both miR-223 and Mef2c. Collectively, these results suggest that miR-223 is involved in regulation of granulocytic maturation but is not absolutely required for the production of granulocytes in vivo.

More recent work has identified that miR-223 targets the cell-cycle regulator E2F1 and blocks cell-cycle progression in AML cells, perhaps contributing to differentiation by causing an exit from the cell cycle.30 It has been previously thought that C/EBPα inhibits E2F1, and hence miR-223 may connect these 2 pathways. Conversely, E2F1 binds to and inhibits the transcription of miR-223, forming a negative autoregulatory loop. Mechanistically, miR-223 has also been shown to target IKK-α, a component of the NF-κB pathway. During macrophage differentiation, miR-223 decreased, releasing repression of IKK-α, which then results in induction of p52 and repression of both canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathways. Nevertheless, the cells were more responsive to proinflammatory stimuli, with greater induction of noncanonical NF-κB target genes.31 These results extend the roles of miR-223 to monocyte/macrophage differentiation, in addition to the previous description of a role in granulocytic differentiation.

miR-146a

miR-146a was initially found during a systematic effort to identify miRNAs that are important in the innate immune response to microbial infection.32 These initial studies confirmed that miR-146a is a transcriptional target of NF-κB, and it was hypothesized that it may serve as a feedback inhibitor of NF-κB activation. In the hematopoietic system, miR-146a expression is found at relatively high levels in mature immune cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), peritoneal macrophages and granulocytes, and splenic B and T cells.33,34 In addition, miR-146a expression was rapidly induced in primary mouse myeloid cells and human monocytic cells on exposure to various TLR ligands, including LPS and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides, as well as proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α.32,33,35,36 Infection of mouse macrophages with vesicular stomatitis virus also up-regulated miR-146a expression.35 The expression pattern of miR-146a suggests that it may play an important role in myeloid biology.

miR-146a appears to play a significant role in bone marrow development of various hematopoietic lineages. Overexpression of miR-146a inhibits megakaryopoiesis in a cell-autonomous manner via a PLZF/miR-146a/CXCR4 regulatory pathway and/or by indirectly suppressing inflammatory cytokine production from myeloid cells.37,38 Moreover, stable knockdown of both miR-145 and miR-146a concurrently with a “sponge” in mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) resulted in thrombocytosis in vivo and increased megakaryocyte colony formation, variable neutropenia, and decreased myeloid colony-forming ability of marrow cells.34 The reduced levels of miR-145 and miR-146a clearly resulted in dysregulated hematopoiesis, but the contribution of the individual miRNAs to the phenotypes requires clarification. To better define the function of miR-146a in the hematopoietic system, a mutant mouse with targeted germline deletion of the miR-146a gene was generated. The miR-146a homozygous knockout mice (miR-146a−/−) were born at the expected frequency and showed no obvious abnormality early on. When allowed to age naturally, miR-146a−/− mice develop a progressive myeloproliferative phenotype involving both the spleen and the bone marrow, beginning at 6 months of age, which eventually progresses to splenic myeloid sarcoma and bone marrow failure at approximately 18 months of age.33,39

TRAF6 and IRAK1 are miR-146a targets in myeloid cells, confirmed by 3′-untranslated region luciferase reporter assay and immunoblot analysis, in a combination of overexpression and loss-of-function studies in primary cells and in cell lines.32-35,39 The functional relevance of TRAF6 as a miR-146a target was demonstrated by enforced expression of TRAF6 in mouse HSPCs, which resulted in some of the same phenotypes as knockdown of miR-145 and miR-146a together, progressing to bone marrow failure or AML.34 This is to some extent reminiscent of aged miR-146a−/− mice that show either myeloproliferative bone marrow or end-stage marrow fibrosis/failure with peripheral pancytopenia.33,39 Moreover, the myeloproliferative phenotype observed in miR-146a-deficient mice is shown to be primarily the result of increased NF-κB activation because reduction in the NF-κB level by deleting the NF-κB subunit p50 effectively rescues the myeloproliferative phenotype.39 These studies suggest the following molecular circuitry regulating myeloid development (Figure 3). After induction by NF-κB, miR-146a feeds back to negatively regulate TRAF6 and IRAK1, 2 of the signal transducers upstream of NF-κB activation. Therefore, it appears that miR-146a, by repressing TRAF6 and IRAK1, may have an effect on NF-κB activation, dampening and/or terminating signals upstream of NF-κB via a negative feedback loop (Figure 3). Because NF-κB regulates both normal as well as malignant hematopoiesis,40-42 these recent discoveries uncover an integral role for miRNA in the regulation of myeloid development.

Summary of miR-146a regulation and functions. Transcription of miR-146a is thought to be induced by transcription factors NF-κB and c-ETS while possibly repressed by c-myc and PLZF. miR-146a targets mRNAs of TRAF6, IRAK1, and STAT1, among others, leading to decreased NF-κB activation and/or decreased IFN response. Overall, miR-146a has a repressive effect on myeloid cell development, NF-κB–induced inflammation, and the development of autoimmunity and hematopoietic malignancies.

Summary of miR-146a regulation and functions. Transcription of miR-146a is thought to be induced by transcription factors NF-κB and c-ETS while possibly repressed by c-myc and PLZF. miR-146a targets mRNAs of TRAF6, IRAK1, and STAT1, among others, leading to decreased NF-κB activation and/or decreased IFN response. Overall, miR-146a has a repressive effect on myeloid cell development, NF-κB–induced inflammation, and the development of autoimmunity and hematopoietic malignancies.

In addition to regulating myeloid development, miR-146a has been shown to regulate mature myeloid cell function in the innate immune system.43 Consistent with the original observation in human monocytic THP1 cell, miR-146a was induced in mouse primary macrophage on TLR ligands and microbial stimulation.33,35,44 The same molecular circuitry involving miR-146a, TRAF6/IRAK1, and NF-κB seems to be also important in mature myeloid cell function. Consistent with this idea, miR-146a−/− mice were more sensitive to systemic LPS challenge, and bone marrow-derived macrophages from miR-146a−/− showed a significant increase in inflammatory cytokine production, such as IL-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α, on LPS stimulation.33 The importance of miR-146a as a negative regulator of inflammation was also demonstrated in the context of endotoxin-induced tolerance in human monocytes. TRAF6 and IRAK1 were again shown to be the responsible miR-146a targets.36,45 In addition, miR-146a induced by vesicular stomatitis virus infection of mouse peritoneal macrophage negatively regulated type I IFN production by targeting TRAF6, IRAK1, and IRAK2 through a TLR4/MyD88-independent but RIG-I/ NF-κB–dependent pathway.35 This finding is further supported by a study in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells showing that miR-146a is a negative regulator of type I IFN pathway. STAT1 and IRF5 were suggested as additional putative targets of miR-146a for regulating type I IFN pathway, based on luciferase reporter assay and overexpression study in 293T cells.46

Recent studies have also associated miR-146a with a range of human hematopoietic diseases. Starczynowski et al showed that miR-146a is down-regulated in clinical samples of 5q- syndrome and stable knockdown of miR-145 and miR-146a concurrently in mouse HSCs recapitulates many features of human 5q- syndrome, a subtype of myelodysplastic syndrome.34,47 In addition, miR-146a has been found to be extensively dysregulated in autoimmune diseases, including lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.33,46,48-50 Although the main cell types in these autoimmune diseases are thought to be activated effector T cells and/or defective regulatory T cells, myeloid cells may also contribute to the overall autoimmune inflammation. There is also some evidence suggesting a role of miR-146a up-regulation in inhibiting atherosclerosis via targets TLR-4 and CD40L in low-density lipoprotein–induced macrophages and DCs, respectively.51,52

Despite recent advances, dissecting out the role of miR-146a and its relevant targets in myeloid cell development and function during both steady state and inflammatory/infectious challenge remains an important area of research. In addition, more efforts are needed to understand the pathogenesis of human diseases with dysregulated miR-146a expression and explore the possibility of delivering miR-146a mimics as a therapeutic strategy.

miR-155

mir-155 was among the first miRNAs identified in the hematopoietic system because of its enhanced expression levels in certain types of lymphomas.53-55 Under steady-state conditions, miR-155 is expressed at low levels in most hematopoietic cells with basal expression higher in HSPCs compared with other more mature bone marrow lineages.35 For instance, miR-155 has been shown to be substantially down-regulated in developing erythrocytes.56 Differential expression is also noted in mature immune cells. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)–derived DCs express significantly higher basal levels of miR-155 compared with M-CSF–derived macrophages.57,58 This may reflect the fact that GM-CSF is produced primarily during inflammatory responses where miR-155 seems to play a specialized role.

During times of inflammatory stress, miR-155 expression is rapidly up-regulated in cells of the GM lineage, including macrophages and DCs by a wide range of TLR ligands and proinflammatory cytokines (Figure 4).32,57-59 In contrast, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 represses miR-155.60 The regulation of BIC, the noncoding RNA that is processed to produce mature miR-155, is under the transcriptional control of NF-κB and AP-1 when myeloid cells are exposed to inflammatory stimuli.58,61 Whereas these factors increase BIC transcription, Stat3 and Akt appear to down-modulate BIC transcript levels.60,62 Hoxa9 has also been shown to regulate miR-155 in HSPCs and appears to do so in these immature cell types in the absence of inflammatory cues.63 Evolutionarily conserved cis-regulatory sites for some of these transcription factors have been identified upstream from the BIC gene.

Summary of miR-155 regulation and functions. Transcription of miR-155 is up-regulated by the transcription factors NF-κB, AP-1, Myb, and HoxA9 and inhibited by Stat3- and Akt-dependent pathways. miR-155 targets mRNAs encoding Ship1, Socs1, as well as other proteins. Inhibition of Ship1 and Socs1 by miR-155, which themselves normally inhibit inflammatory responses, leads to enhanced activation of proinflammatory pathways. Functionally speaking, miR-155 has been shown to promote myeloid development and function and play a positive role in the promotion of cancer and autoimmunity.

Summary of miR-155 regulation and functions. Transcription of miR-155 is up-regulated by the transcription factors NF-κB, AP-1, Myb, and HoxA9 and inhibited by Stat3- and Akt-dependent pathways. miR-155 targets mRNAs encoding Ship1, Socs1, as well as other proteins. Inhibition of Ship1 and Socs1 by miR-155, which themselves normally inhibit inflammatory responses, leads to enhanced activation of proinflammatory pathways. Functionally speaking, miR-155 has been shown to promote myeloid development and function and play a positive role in the promotion of cancer and autoimmunity.

After transcription of BIC, the miR-155 hairpin is processed into mature miR-155 through a Dicer-dependent pathway. This process involves KSRP, which binds to the loop region of miR-155 and promotes its processing.64 Once loaded into the RISC complex, miR-155 initiates target repression. Although little is known about what factors control the stability of mature miR-155, it is present in cells hours after its primary transcript is undetectable.58

To date, miR-155 has been shown to impact both early hematopoietic development and the functions of specific mature immune cell types. Initial studies looking at the role of miR-155 in the hematopoietic compartment found that sustained overexpression of miR-155 causes a myeloproliferative disorder in the bone marrow and splenomegaly as a result of expanded splenic hematopoiesis.21 During competitive repopulation assays, miR-155 conferred an advantage to engrafting bone marrow, indicating that miR-155 promotes HSC output of downstream lineages with a bias toward myeloid cells.35 Further supporting this role, myeloid colony formation mediated by HoxA9 was blunted in the absence of miR-155.63 This phenotype induced by miR-155 is similar to that observed in mice deficient in Ship1, a negative regulator of cytokine signaling.65 Ship1 has been shown to be directly targeted by miR-155, suggesting it is a downstream effector.66,67 Taken together, these data support a model whereby miR-155 is induced in HSPCs and developing myeloid progenitor cells during inflammatory responses, and in turn, augments production of mature myeloid cells.

Recent studies have assessed the role of miR-155 in primary macrophages and DCs, finding that in many cases it promotes expression of inflammatory cytokines and the IFN response. This probably occurs via repression of the negative regulators SOCS1 and SHIP1, both direct targets of miR-155.57,62 Through the down-regulation of these anti-inflammatory pathways, miR-155 also promotes endotoxemia in mice.62 Therefore, miR-155 not only impacts myeloid development but also the functional capacity of inflammatory myeloid cell populations during immune responses.

In addition to Ship1 and Socs1, miR-155 has been shown to target many other mRNAs encoded by genes with relevance to myeloid biology. These include Bach1, CSFR1, DC-Sign, MyD88, IL-13ra, Tab2, PU.1, and C/EBPβ.21,59,68-70 Interestingly, some of these targets promote inflammatory responses, which is in contrast to Ship1 and Socs1. Still others play well-established roles in cellular differentiation. Adding to this complexity, a recent study took a high-throughput sequencing approach to assess miR-155 targets.71 Interestingly, this study not only identified some novel targets of miR-155 but also found that certain mRNA isoforms lost their miR-155 binding sites because of alternative splicing or differential polyadenylation site usage. Thus, both the array of relevant miR-155 targets coupled with the ability of certain target isoforms to lose their miR-155 binding sites underscores the inherent complexity underlying miR-155 function. This is true not only in myeloid cells, but also in lymphocytes where miR-155 is also expressed.61,72

Like many regulators of hematopoietic development, dysregulation of miR-155 has been linked to diseases, such as cancer and autoimmunity.21,57,73 The myeloproliferative disorder observed in miR-155 expressing mice resembles a preleukemic condition, and AML patients with mutations in FLT3 have elevated miR-155 levels in their leukemic blasts.74 Enrichment of miR-155 has been observed in lesions biopsied from MS patients.73 Using a mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a role for mIR-155 during autoimmune inflammation has been identified. miR-155–deficient mice were significantly resistant to EAE because of a deficit in inflammatory T-cell development.57 Although a majority of miR-155's contribution to EAE was T cell intrinsic, defects in myeloid DC function were also observed in the absence of miR-155. Taken together, miR-155 is emerging as a promising therapeutic target that may be exploited therapeutically to combat different types of human diseases involving the hematopoietic system.

miR-125 family

Another family of miRNAs with emerging importance in myeloid biology is miR-125, which is homologous to Caenorhabditis elegans lin-4.75 The 3 members of the miR-125 family include miR-125a, miR-125b1, and miR-125b2. Each is found in a different location within the genome and produced from a primary transcript that also contains an miR-99/miR100 and let7 family member.76 It is not yet clear whether these different polycistrons play unique or redundant roles in mammalian biology or whether the 3 different miRNAs produced by the transcript are functionally linked. However, it is probable that these duplicated clusters are under distinct transcriptional control and will therefore exhibit differential expression patterns and thus functions.

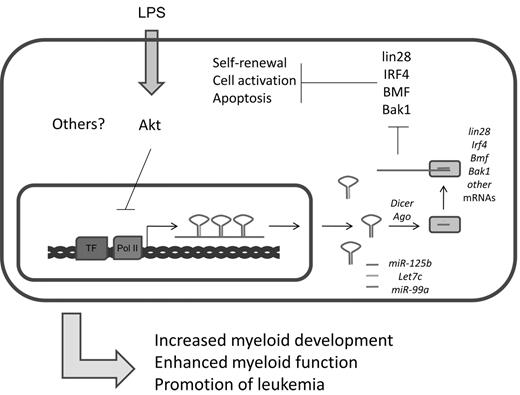

In addition to their strong expression in the nervous system,75 several groups have recently found enrichment of miR-125a and miR-125b expression in mouse and human HSCs.19,35,77 Studies indicate that miR-125 family members, which presumably have the same set of cellular target mRNAs because of their identical seed sequences, can positively impact HSC engraftment and output of mature hematopoietic cells. There is evidence that miR-125 directly targets and down-regulates proapoptotic factors, such as Bak1, KLF13, and BMF (Figure 5).19,77 Indeed, it has been shown that miR-125 can increase the survival of immature hematopoietic cell populations, and this may underlie its function in HSCs.19,78 miR-125 also strongly represses the pluripotency factor Lin28.79 In embryonic stem cells, siRNA knockdown of Lin28 inhibits cellular differentiation, but the consequences of this regulation in the hematopoietic system remains unstudied.80 Based on these observations, it is plausible that miR-125 might regulate the balance between HSC self-renewal and differentiation through modulation of Lin28 levels. Beyond these examples, many additional targets of miR-125 have been reported,81,82 and this suggests that miR-125 modulates a complex network of proteins involved in cell survival and differentiation. miR-125b is also expressed in bone marrow– derived macrophages where its levels are reportedly down-regulated in response to LPS treatment.62,83 At the transcriptional level, regulation of the primary transcript that produces miR-125b is controlled in part by the Akt pathway.62 Despite its expression in this cellular compartment, a defined role for miR-125b in macrophage biology remains to be found.

Summary of miR-125b functions. miR-125b is part of an miRNA locus that encodes other important miRNAs. It is cotranscribed with let-7c and miR-99a. Important targets of miR-125b include several factors important in the maintenance of stem cell properties and cell survival and apoptosis, including lin28, IRF4, BMF, and Bak1.

Summary of miR-125b functions. miR-125b is part of an miRNA locus that encodes other important miRNAs. It is cotranscribed with let-7c and miR-99a. Important targets of miR-125b include several factors important in the maintenance of stem cell properties and cell survival and apoptosis, including lin28, IRF4, BMF, and Bak1.

Similar to miR-155, miR-125b1 was initially identified in the hematopoietic compartment because of its elevated expression in AML and MDS,84 and it has also been shown to be overproduced in megakaryocytic leukemia.81 When miR-125b is expressed at high levels in mice, it causes an initial myeloproliferative disorder, which converts to a lethal, frank leukemia within months.35,85 In some ways, this phenotype resembles chronic myeloid leukemia, which also begins with a chronic overproduction of myeloid cells followed by progression to a blast crisis. After coexpression of miR-125b along with BCR-ABL, an accelerated malignancy was observed compared with enforced expression of BCR-ABL alone.85 Future studies will assess whether miR-125 family members are involved in establishing leukemia-initiating stem cells and, if so, whether therapeutic targeting of certain miR-125 family members can be used as an effective treatment against leukemia by eradicating cancer stem cells.

Other miRNAs important in myeloid development, function, and diseases

miR-29a is enriched in the long-term HSCs, compared with the lineage-committed progenitor cells in mouse and human.86 Overexpression of miR-29a in mouse HSPCs promotes myeloid cell differentiation and induces AML. The mechanism of leukemogenesis in miR-29a–overexpression mice is thought to involve the conversion of myeloid progenitor cells into self-renewing leukemia stem cells and the promotion of cell-cycle progression. Several targets of miR-29a have been proposed, but the one(s) responsible for miR-29a–induced myeloid proliferation remain(s) to be determined.86 More interestingly, a related family member with an identical seed region, miR-29b, functions as a tumor suppressor miRNA in AML.87-90 miR-29b is shown to target several DNA methytransferases and, when ectopically expressed, induces tumor suppressor gene reexpression in AML cells.89 Phenotypically, the restoration of miR-29b expression in AML cell lines and primary AML samples can inhibit tumorigenicity and induce apoptosis of the leukemic cells.89 This suggests an interesting functional dichotomy of closely related miRNA family members and emphasizes the importance of studying the functions of miRNA and its targets in a relevant cellular context.

Gfi1 is an important transcriptional repressor required for normal granulopoiesis. miR-21 and miR-196b are shown to be transcriptionally repressed by Gfi1 during normal granulopoiesis, and overexpression of miR-21 and miR-196b together completely blocks G-CSF-induced granulopoiesis in vitro. This is very similar to Gfi1−/− mice and patients with a genetic GFI1 loss-of-function mutation.91 In mature myeloid cells, miR-21 is induced in macrophages after LPS stimulation. After induction, miR-21 is shown to be a negative regulator of TLR4 signaling by targeting a proinflammatory tumor suppressor, PDCD4.92

Other miRNAs have been ascribed various roles in hematopoietic differentiation. miR-451, a Dicer-independent miRNA, plays a critical role in erythropoiesis in the mouse and zebrafish models.5,6 A cluster of microRNAs (miR-17-5p-20a-106a) has been shown to control monocyte differentiation and maturation by targeting AML1 (also known as Runx1). During monocytopoiesis, reduced expression of the miRNA 17-5p-20a-106a cluster led to de-repression of AML1, which in turn increased expression of M-CSF receptor and promoted monocyte differentiation and maturation.92,93 miR-124 has been shown to suppress autoimmune inflammation (using a EAE model) by deactivating macrophages through the C/EBPα–PU.1 pathway.94

Recent work has also revealed some novel roles for miRNAs in myeloid development. miR-328 has been demonstrated to profoundly influence both the differentiation and survival of leukemic blasts in chronic myeloid leukemia by interacting with hnRNP E2 protein and with PIM1 mRNA. Interestingly, although the repression of PIM1 mRNA by miR-328 is through canonical seed pairing, the interaction with hnRNP E2 is seed sequence-independent, and this interaction alleviates C/EBPα mRNA from hnRNP E2-mediated translational inhibition.95 miR-203 and the miR-17-92 cluster appear to have roles in regulating leukemia stem cell survival by targeting ABL (the tyrosine kinase translocation partner of BCR in chronic myeloid leukemia) and p21, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, respectively.96,97 miR-34a, the first identified miRNA to be transcriptionally activated by p53, is also induced by C/EBPα and targets E2F3 during granulopoiesis. Here, miR-34a may orchestrate the coordination of exit from the cell cycle with granulocytic differentiation.98

In conclusion, in this fast-moving field, there have been numerous discoveries that have uncovered paradigms for miRNA function in myeloid biology. We examined the discoveries surrounding 4 miRNAs that have been very intensively studied using a variety of experimental systems to uncover paradigms about miRNA function. From this, we conclude that miRNAs are important in myeloid differentiation and activation and that specific miRNAs are embedded within transcriptional networks, revealing previously unrecognized connections between cellular pathways that regulate cellular differentiation. miRNAs also can serve in positive (miR-223; Figure 2) and negative feedback circuits (miR-146a; Figure 3) and may confer certain unique regulatory properties on the networks they regulate. For example, miR-155 may be important in the kinetics of the immune response as it can regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally, without the need for translation of a protein effector. Because they act on a preexisting mRNA, miRNA function is highly dependent on the cell type in which it is induced, and the same miRNA may have very different functions in different cell types. This may be the case with miR-223, where expression in leukemic blasts promotes differentiation, but its loss of function in all hematopoietic cells results in granulocytosis. Hence, the ongoing study of miRNAs will both require and promote conceptual advances in myeloid biology.

There is no doubt that the 4 miRNAs explored in-depth here are important in myeloid biology, but ongoing work suggests that additional miRNAs will also emerge as highly important, and some of these have been documented in the preceding paragraphs. Further research will probably focus on analysis of the targets of these various miRNAs, including sorting out whether single or a few targets are critical physiologically, the roles of target alternative splicing and polyadenylation in regulating miRNA-target interactions, and noncanonical roles of miRNA in gene regulation. In addition, analysis of targets in miRNA-dysregulated myeloid diseases will provide additional druggable targets for therapeutic development. Of course, miRNAs themselves may provide the most valuable targets as RNA-based inhibition can be designed based on sequence alone. On a hopeful note, technologies for the delivery of small RNAs have now been demonstrated in both animal models and in human patients.99,100 Specifically, targeting miR-155 and miR-125b for down-regulation and restoring miR-223 and miR-146a in myeloid cancers could provide a powerful way to modulate the growth properties of these neoplasms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Baltimore for helpful discussions over the years regarding miRNA biology and pathology.

D.S.R. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (career development award 5K08CA133521). R.M.O. was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (award K99HL102228). J.L.Z. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (joint University of California Los Angeles/Caltech Medical Scientist Training Grant).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: D.S.R. planned and reviewed all sections of the review; and all authors wrote sections of the review and generated the figures.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for R.M.O. is Division of Microbiology and Immunology, Department of Pathology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT.

Correspondence: Dinesh S. Rao, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California Los Angeles, 650 Charles E. Young Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90095; e-mail: drao@mednet.ucla.edu.

References

Author notes

R.M.O. and J.L.Z. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal