Abstract

Although the maintenance of HSC quiescence and self-renewal are critical for controlling stem cell pool and transplantation efficiency, the mechanisms by which they are regulated remain largely unknown. Understanding the factors controlling these processes may have important therapeutic potential for BM failure and cancers. Here, we show that Skp2, a component of the Skp2 SCF complex, is an important regulator for HSC quiescence, frequency, and self-renewal capability. Skp2 deficiency displays a marked enhancement of HSC populations through promoting cell cycle entry independently of its role on apoptosis. Surprisingly, Skp2 deficiency in HSCs reduces quiescence and displays increased HSC cycling and proliferation. Importantly, loss of Skp2 not only increases HSC populations and long-term reconstitution ability but also rescues the defect in long-term reconstitution ability of HSCs on PTEN inactivation. Mechanistically, we show that Skp2 deficiency induces Cyclin D1 gene expression, which contributes to an increase in HSC cycling. Finally, we demonstrate that Skp2 deficiency enhances sensitivity of Lin− Sca-1+ c-kit+ cells and leukemia cells to chemotherapy agents. Our findings show that Skp2 is a novel regulator for HSC quiescence and self-renewal and that targeting Skp2 may have therapeutic implications for BM transplantation and leukemia stem cell treatment.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is an important process that yields every type of blood cell for body needs. HSCs, which include long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs) and short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs), are the primary sources for hematopoiesis. LT-HSCs not only have self-renewal capability to maintain HSC pool, but can also differentiate into multipotent progenitors that can further differentiate into lymphoid progenitors and myeloid progenitors for subsequent generations of mature blood cells. In contrast, ST-HSCs only have limited self-renewal ability, although they also differentiate into multipotent progenitors as well.

The maintenance of the HSC pool and its functions are critical for preventing BM failure and for ensuring lifetime hematopoiesis. Although quiescence and self-renewal of HSCs are crucial for maintaining the HSC pool and function, the mechanisms by which these processes are regulated remains largely unknown. Recent studies, however, suggest that cell cycle inhibitors regulate pool size and function of HSCs and progenitors. For example, loss of p21 increases HSC populations and cycling.1,2 In addition, loss of p27 markedly alters progenitor proliferation and pool size, although it does not affect stem cell number, cell cycling, and self-renewal capability.3 Phosphate and tensin homologue (PTEN) is also known to be a key regulator for HSC function. PTEN deficiency promotes HSC proliferation and leads to transient expansion of HSC number, but gradually exhausts HSC pool and results in the failure of long-term reconstitution ability of HSCs.4,5 Although how exactly PTEN deletion regulates these phenotypes remains elusive, it is speculated that hyperactivation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 may be involved.4,5

Skp2 (S-phase kinase associated protein-2), a member of F-box proteins, forms the Skp2 SCF complex with Skp1, Cullin-1, and Rbx1, and is responsible for substrate recognition.6,7 The Skp2 SCF complex has been shown to trigger ubiquitination and degradation of cell cycle inhibitors such as p27 and p21 and, in turn, trigger cell cycle progression.6-8 Skp2 is overexpressed in a variety of human cancers and promotes cancer progression by inducing p27 degradation.9,10 Importantly, Skp2 deficiency profoundly restricts cancer progression in multiple genetic mouse tumor models.11-13 Because we have recently identified Skp2 as a critical downstream effector for tumorigenesis on PTEN inactivation,13 we speculate that Skp2 may also play an important role in the regulation of HSC pool and function.

In this study, we aim to examine the role of Skp2 in HSC functions. Our study shows that Skp2 is a crucial regulator for the maintenance of HSC quiescence, pool size, and self-renewal capability.

Methods

Mice and cells

Skp2−/− and PTEN+/− mice were maintained in 129 and C57/B6 mixed backgrounds. To obtain the PTEN+/−Skp2−/− compound mice, Skp2−/− mice were crossed with PTEN+/− mice, and the F1 mice were further intercrossed. All animal experiments were performed according to our Animal Care and Use Form animal protocol, approved by M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. The primer sequences for Skp2 and PTEN used in genotyping were described previously.14-16

Cell sorting and flow cytometric analysis

BM cells from 8- to 12-week-old mice were collected, and total cell numbers were counted and normalized by body sizes of mice (average body sizes of Skp2 knockout mice were ∼ 30% of WT mice17 ). The BM cells were then stained with antibodies against various cell surface markers and sorted by flow cytometry to obtain LT-HSCs and Lin− Sca-1+ c-kit+ (LSK) cells. The antibodies for surface markers included biotin-conjugated antibodies against 7 lineage markers (CD3, CD5, CD8, CD11b, Gr-1, B220, and Ter119; BD Bioscience), Sca-1 (PE-Cy5.5 conjugated; BD Bioscience), c-Kit (APC conjugated; BD Bioscience), CD34 (FITC conjugated; BD Bioscience), and Flk-2 (PE conjugated; BD Bioscience).18 We also labeled the HSC populations with another set of surface markers, Lin, Sca-1, c-Kit combined with CD150 (PE conjugated; BD Bioscience) and CD48 (FITC conjugated; BD Bioscience) instead of CD34 and Flk-2.19 We performed most experiments with the first set of surface markers unless otherwise indicated. Total BM cells or sorted HSCs were cultured in HSC medium containing 10% BSA in ex vivo medium supplied as well as IL-3 (PeproTech) and SCF (PeproTech). Granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMPs; Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34+CD16/CD32+) were isolated as described.19 In brief, we labeled the freshly isolated BM cells with Lineage, Sca-1, c-Kit, CD34, and CD16/CD32 (PE conjugated) antibodies to obtain a subset population of GMPs from LSK cells. The flow profile of GMPs is shown in supplemental Figure 2, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed as described.17 In brief, sorted LT-HSCs were cultured for 1 week, washed once with PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol at 4°C for 24 hours. Cells were then stained with 1 mL of propidium iodide (50 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μL RNase (1.0 mg/mL; Roche). After incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes in the dark, cell cycle profile was analyzed by flow cytometric assay. To dissect the G1 and G0 phases, BM cells were mixed with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma-Aldrich; 2 μg per million cells) at 37°C for 45 minutes and incubated with Pyronin Y (Sigma-Aldrich) to the final concentration of 1 μg/mL for another 45 minutes at 37°C in the dark. These stained cells were then incubated with antibodies against various surface markers (Lineage, Sca-1, c-Kit, CD34, and Flk-2) before flow cytometric analysis. We set up the gating according to LSK cells and then applied to LT-HSCs.

In vivo BrdU incorporation assay

The in vivo BrdU incorporation assay was essentially described.19 In brief, WT and Skp2−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with BrdU (1 mg per 6 g of body weight). Twenty-four hours after the injection, we collected BM and spleen cells from mice, stained them according to the instruction of the BrdU staining kit (BD PharMingen), and then analyzed BrdU-positive Flk-2 negative LSK cell frequency by flow cytometry.

Colony-forming assay

BM cells (20 000 cells) were seeded in 24-well plate in triplicates and cultured in HSC medium supplemented with methylcellulose for ∼ 5-7 days according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems). The colony number was counted with a conventional light microscope.

Long-term culture-initiating cell assay

Feeder cells were prepared from freshly isolated BM cells and cultured in M5300 with 10−6M hydrocortisone (StemCell Technologies) and then irradiated with 15 Gy when cells reached 90% confluence. BM cells (15 000, 30 000, and 70 000) isolated from WT and Skp2−/− mice were seeded in 96-well plates. After 4 weeks of culture, all cells in each well were transferred into a 35-mm culture dish supplemented with methylcellulose containing culture medium M3434 (StemCell Technologies). After 1-2 weeks of culture, colonies were counted.

Serial transplantation assay and competitive repopulation assay

Serial transplantation was performed as described. In brief, BM cells (2 million) from donor female WT and Skp2−/− mice at the age of 8-12 weeks were injected into lethally irradiated recipient mice through the tail vein. The recipient mice, bought from The Jackson Laboratory, were also 129 and C57/B6 mix background like the donor mice. Three weeks after transplantation, a complete blood cell (CBC) count test was performed in the M. D. Anderson core facility. For the second round of transplantation, BM cells from the recipient mice were isolated 6 weeks after the first round of transplantation and injected into the recipient mice. CBC count test was performed 3 weeks after transplantation. The same procedures were applied to the third, fourth, and fifth round of the transplantation. To confirm that the reconstitution of hematopoiesis was from donor male mice, we analyzed the Y chromosome of genomic DNA from BM cells of female recipient mice with the use of the PCR method. The primer sequences for the mouse Y chromosome were forward, 5′-TCATGAGACTGCCAACCACAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-CATGACCACCACCACCACCACCAA-3′. For competitive repopulation assay, 2 groups of BM cells (first group, WT donor BM cells mixed with WT competitor BM cells at 1:1 ratio; the second group, Skp2−/− donor BM cells were mixed with WT competitor BM cells at 1:1 ratio) were injected into lethally irradiated recipients. The mice survival was monitored after injection.

Viral infection

For lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) infection, 293T cells were cotransfected with shRNA (to knockdown Skp2 and Cyclin D1) and packing plasmids p-Helper and p-Envelope, following calcium-phosphate transfection methods. Skp2 lentiviral shRNA sequences were listed in the literature.20 Cyclin D1 lentiviral shRNA sequences were (1) 5′-CTTTCTTTCCAGAGTCATCAA-3′ and (2) 5′-CCACGATTTCATCGAACACTT-3′. Forty-eight hours after transfection, target cells were infected with virus particles. Infected mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and K562 and KBM5 cells were selected by 2 μg/mL puromycin, and cell lysates were collected for Western blot analysis to confirm the knockdown efficiency. Virus particles expressing Cyclin D1 shRNAs were used to infect BM cells from Skp2−/− mice for 2 days, and these cells were subjected to G1/G0 cell cycle analysis. Cyclin D1 knockdown efficiency was shown in MEF cells.

Western blot analysis

LSK cells were harvested and lysed with RIPA buffer (1 × PBS, 1% Nonidet P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche) after culturing for 1 week. Immunoblotting was performed with standard protocols as previously described.21 Antibodies used for Western blot analysis included anti-p21 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-p27 (BD Biosciences), anti-Cylin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Skp2 (Invitrogen), and anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from LT-HSCs right after sorting with the use of the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). cDNA was subsequently prepared with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with the use of the Applied Biosystems 7300/7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Transcription of Skp2, N-cadherin, β-catenin, Cyclin D1, Cyclin D2, and Cyclin E1 was assessed with the primers listed in supplemental Table 1. GAPDH was used as internal control.

Chemotherapeutic treatment and apoptosis assay

LSK cells isolated from WT and Skp2−/− mice were cultured for 3-5 days, treated with cyclophosphamide (CPA; 500 μg/mL; MP Biomedicals), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; 25 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), or doxorubicin (DOX; 1 μg/mL; Sigma) for 12 hours, and stained with annexin V–FITC (BD Bioscience) for flow cytometric analysis. We also examined the apoptosis rate of freshly sorted LSK cells from BM cells of WT and Skp2−/− mice treated with the chemotherapy agents CPA, 5-FU, and DOX. K562 and KBM5 cells were treated with CPA (3000 μg/mL) or 5-FU (300 μg/mL) for 12 hours, stained with annexin V–FITC (BD Bioscience), and subjected to flow cytometric analysis for the apoptosis assay. For in vivo 5-FU treatment, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 5-FU (5 mg per 20 g of body weight) once per day for 3 days, and BM cells collected on the fifth day were stained with surfaced markers and annexin V, followed by flow cytometric analysis to assess the apoptosis rate of LSK cells.

Statistical analysis

Values were shown as mean ± SD. The statistical analysis was performed with unpaired Student t test. For survival evaluation, Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of cumulative survival in a log-rank test was performed. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Loss of Skp2 increases stem cell pool size by triggering cell cycle entry

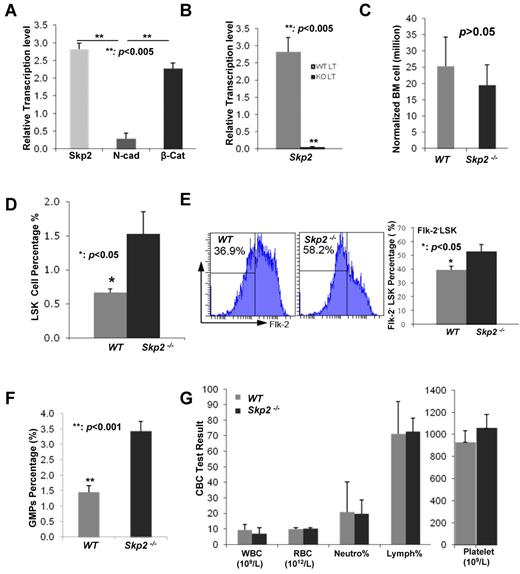

To determine the role of Skp2 in HSC functions, we at first examined whether Skp2 is expressed in HSCs. To this end, we collected BM cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice stained with multiple cell surface markers as shown in “Methods” and sorted LT-HSCs (Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+Flk-2−CD34−) by FACS. We performed real-time PCR to determine the transcription level of Skp2 in LT-HSCs from WT mice compared with that of β-catenin known to express in HSCs22 and found that Skp2 was indeed expressed in LT-HSCs comparable to β-catenin (Figure 1A), but not in Skp2−/− LT-HSCs (Figure 1B). However, we found that the N-Cadherin transcription level was low in WT LT-HSC cells (Figure 1A), consistent with previous reports.23-25

Skp2 regulates stem cell pool size. (A) Analysis of the mRNA level of Skp2, N-Cadherin, and β-catenin in LT-HSCs from WT mice by real-time PCR (**P < .005; n = 4). (B) Analysis of the mRNA level of Skp2 LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice by real-time PCR (**P < .005; n = 4). (C) Total numbers of BM cells per mouse from WT and Skp2−/− mice normalized by their body weights were 25.33 ± 6.22 million in WT BM cells versus 19.5 ± 5.49 million in Skp2−/− BM cells (P > .05; n ≥ 4). (D) Analysis of LSK cell population from WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry. The percentages of LSK cells in WT mice were 0.667% ± 0.058% versus 1.533% ± 0.322% in Skp2−/− mice (*P < .05; n = 3). (E) Analysis of Flk−LSK population in WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry. The percentages of Flk−LSK cells in WT mice were 39.5% ± 2.65% versus 52.8% ± 5.0% in Skp2−/− mice (*P < .05; n = 3). (F) Analysis of GMP populations in WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry. The percentages of GMP cells in WT mice were 1.45% ± 0.21% versus 3.43% ± 0.32% in Skp2−/− mice (**P < .001; n = 4). (G) The CBC test was performed to determine the number of WBCs, RBCs, and platelets and the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes in WT and Skp2−/− mice (P > .05; n = 5).

Skp2 regulates stem cell pool size. (A) Analysis of the mRNA level of Skp2, N-Cadherin, and β-catenin in LT-HSCs from WT mice by real-time PCR (**P < .005; n = 4). (B) Analysis of the mRNA level of Skp2 LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice by real-time PCR (**P < .005; n = 4). (C) Total numbers of BM cells per mouse from WT and Skp2−/− mice normalized by their body weights were 25.33 ± 6.22 million in WT BM cells versus 19.5 ± 5.49 million in Skp2−/− BM cells (P > .05; n ≥ 4). (D) Analysis of LSK cell population from WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry. The percentages of LSK cells in WT mice were 0.667% ± 0.058% versus 1.533% ± 0.322% in Skp2−/− mice (*P < .05; n = 3). (E) Analysis of Flk−LSK population in WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry. The percentages of Flk−LSK cells in WT mice were 39.5% ± 2.65% versus 52.8% ± 5.0% in Skp2−/− mice (*P < .05; n = 3). (F) Analysis of GMP populations in WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry. The percentages of GMP cells in WT mice were 1.45% ± 0.21% versus 3.43% ± 0.32% in Skp2−/− mice (**P < .001; n = 4). (G) The CBC test was performed to determine the number of WBCs, RBCs, and platelets and the percentage of neutrophils and lymphocytes in WT and Skp2−/− mice (P > .05; n = 5).

Having shown that Skp2 was expressed in LT-HSCs, we next determined whether Skp2 regulates HSC pools. The total numbers of BM cells from Skp2−/− mice were comparable to those from WT mice after normalization of mouse body size (Figure 1C). We then isolated LSK cells, which include LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and early progenitors, with the of Lin, Sca-1, and c-Kit surface markers. Surprisingly, the LSK cell frequency in Skp2−/− mice was significantly higher than in WT mice (Figure 1D), indicating that the numbers of LSK cells in Skp2−/− mice are higher than those in WT mice. The frequency of Flk-2− LSK cells (Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+Flk-2−) was also higher in Skp2−/− mice than in WT mice (Figure 1E). To further confirm this phenomenon, we labeled BM cells with another set of surface markers, including Lin, Sca-1, c-Kit, CD150, and CD48, and found that the HSC population (Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−) was increased in Skp2−/− mice (supplemental Figure 1A-B). We also examined the frequency of GMPs (Lin−Sca-1−c-Kit+CD34+CD16/CD32+) labeled with surface markers and found that the GMP population was higher in Skp2−/− mice than in WT mice (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure 2). These results suggest that Skp2 is a key factor that negatively regulates HSC pools and GMP populations. However, loss of Skp2 does not affect steady-state hematopoiesis, because the numbers of mature blood cell lineages, such as white blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), platelet, neutrophil, and lymphocyte, were comparable between WT and Skp2−/− mice (Figure 1G).

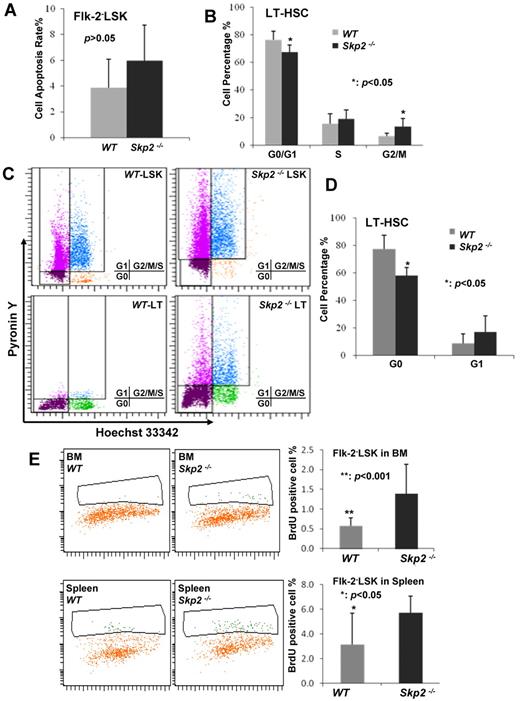

To understand the mechanism by which Skp2 regulates the HSC pool, we determined whether the rate of apoptosis is altered in Skp2−/− Flk-2−LSK cells because Skp2 was previously shown to regulate apoptosis in MEFs and cancer cells.17,20 We found that there was no significant change in the apoptotic rate between WT and Skp2−/− Flk-2−LSK cells with the use of anexin V staining and flow cytometric analysis (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3). Because Skp2 is known to promote cell cycle entry and cell proliferation by targeting p27 degradation in primary MEFs and cancer cells,17,20 we sought to determine whether Skp2 deficiency affects cell cycle progression and in turn regulates the LSK pool. Unexpectedly, Skp2-deficient LT-HSCs displayed a reduction in G1/G0 phase (66.87% ± 5.38% vs 76.4% ± 6.3%; P < .05) but a significant increase in G2/M phase (12.33% ± 3.17% vs 6.8% ± 1.9%; P < .005) compared with WT (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 4), indicating that Skp2 deficiency promotes LT-HSC cycling and proliferation, which may in turn increase HSC pools.

Loss of Skp2 triggers the HSCs entering the cell cycle. (A) Analysis of apoptosis in LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry (P > .05; n = 3). (B) Cell cycle profile of LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice was determined by flow cytometric analysis (*P < .05; n = 3). The representative histogram is shown in supplemental Figure 4. (C-D) Flow cytometric dot plot and statistical results of G0 and G1 phase cells in LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− (*P < .05; n = 3). (E) The BrdU incorporated rates of Flk−LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice were 0.578% ± 0.199% versus 1.389% ± 0.742% in BM (**P < .01; n = 3) and 3.122% ± 2.553% versus 5.722% ± 1.340% in spleen (*P < .05; n = 3).

Loss of Skp2 triggers the HSCs entering the cell cycle. (A) Analysis of apoptosis in LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice by flow cytometry (P > .05; n = 3). (B) Cell cycle profile of LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice was determined by flow cytometric analysis (*P < .05; n = 3). The representative histogram is shown in supplemental Figure 4. (C-D) Flow cytometric dot plot and statistical results of G0 and G1 phase cells in LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− (*P < .05; n = 3). (E) The BrdU incorporated rates of Flk−LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice were 0.578% ± 0.199% versus 1.389% ± 0.742% in BM (**P < .01; n = 3) and 3.122% ± 2.553% versus 5.722% ± 1.340% in spleen (*P < .05; n = 3).

LT-HSCs mainly stay in quiescence through their interaction with the BM osteoblast niche. The observation that Skp2 deficiency promotes HSC cycling and proliferation led us to postulate that Skp2 may play a critical role in maintaining HSCs in the quiescent stage. Consistent with this notion, we found that Skp2 deficiency significantly reduced LT-HSCs in the G0 phase but not in the G1 phase, compared with WT LT-HSCs (58.17% ± 5.66% vs 77.37% ± 9.90%; P < .05; Figure 2C-D), suggesting that Skp2 maintains HSCs in the quiescent stage, in turn preventing them to enter the cycling phase.

To further corroborate this notion, we performed in vivo BrdU incorporation assay in mice. Consistently, we found that Skp2-deficient Flk-2−LSK cells displayed a much higher BrdU incorporation rate than WT Flk-2−LSK cells (in BM: 1.389% ± 0.742% vs 0.578% ± 0.199%; P < .01; in spleen: 5.722% ± 1.34% vs 3.122% ± 2.553%; P < .05; Figure 2E). Similarly, the BrdU incorporation rate in Skp2-deficient LSK cells was also higher than that in WT LSK cells (supplemental Figure 5). Taken together, these results suggest that Skp2 is an essential factor in maintaining LT-HSCs in the quiescent stage because its deficiency leads to LT-HSC cycling and proliferation, in turn expanding the stem cell pool.

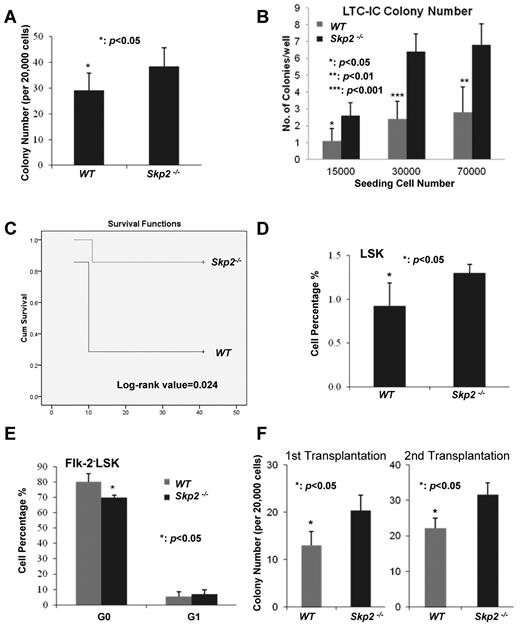

Skp2 deficiency enhances proliferation and long-term reconstitution ability of HSCs

To study the role of Skp2 in HSC functions, we next examined whether Skp2 affects the colony-forming ability of HSCs, and thereby regulating the proliferation and self-renewal ability of HSCs. Consistent with the observation that Skp2 deficiency promotes cell cycle entry and proliferation of LT-HSCs, Skp2 deficiency significantly enhanced the colony-forming ability of BM cells (Figure 3A; P < .05). In line with this observation, the long-term culture-initiating cell assay showed that Skp2 deficiency also increased the colony-forming ability of HSCs (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we determined whether Skp2 also regulates the in vivo self-renewal and reconstitution ability of BM stem cells. To this end, we performed serial BM transplantation assay to examine whether there is a difference in the long-term reconstitution ability between WT and Skp2−/− BM cells (supplemental Figure 6). Although there was no significant difference of reconstitution ability in the first, second, and third rounds of transplantation (data not shown), we found that Skp2 deficiency profoundly enhanced the reconstitution ability of HSCs in the fourth and fifth rounds (Figure 3C; data not shown). The log-rank value of 0.024 was obtained with the Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of the fifth round transplantation (Figure 3C). Consistently, the competition assay with a 1:1 ratio showed that Skp2-deficient BM cells reconstituted better in lethally irradiated mice than WT BM cells (supplemental Figure 7). These results therefore suggest that Skp2 deficiency enhances the long-term reconstitution and self-renewal ability of BM stem cells.

Skp2 deficiency enhances the colony-forming ability and long-term reconstitution ability of BM. (A) The colony formation ability of BM cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice (*P < .05; n = 3). (B) The long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) assay results showed that BM cells from Skp2−/− mice had higher colony formation ability than those from WT mice (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; n = 8). (C) Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of cumulative survival of the irradiated recipient mice injected with WT and Skp2−/− BM cells after the fifth round of transplantation (log-rank value = 0.024; n = 5). (D) Analysis of LSK population in WT and Skp2−/− recipient mice by flow cytometry after the first round of transplantation (*P < .05; n = 5). (E) G0 and G1 phases of LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− recipient mice were determined by flow cytometric analysis after the first round of BM transplantation. (*P < .05; n = 5). (F) The colony-forming ability of BM cells from the recipient mice after the first and second round of transplantation (*P < .05; n = 3).

Skp2 deficiency enhances the colony-forming ability and long-term reconstitution ability of BM. (A) The colony formation ability of BM cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice (*P < .05; n = 3). (B) The long-term culture-initiating cell (LTC-IC) assay results showed that BM cells from Skp2−/− mice had higher colony formation ability than those from WT mice (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; n = 8). (C) Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of cumulative survival of the irradiated recipient mice injected with WT and Skp2−/− BM cells after the fifth round of transplantation (log-rank value = 0.024; n = 5). (D) Analysis of LSK population in WT and Skp2−/− recipient mice by flow cytometry after the first round of transplantation (*P < .05; n = 5). (E) G0 and G1 phases of LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− recipient mice were determined by flow cytometric analysis after the first round of BM transplantation. (*P < .05; n = 5). (F) The colony-forming ability of BM cells from the recipient mice after the first and second round of transplantation (*P < .05; n = 3).

When isolating WT and Skp2−/− HSCs from recipient WT mice 6 weeks after the first round of BM transplantation, Skp2 deficiency also increased LSK cell frequency while reducing LT-HSC quiescence (Figure 3D-E). This is consistent with our results (Figures 1D, 2C-D) that Skp2−/− mice displayed an elevation of the LSK pool and a reduction of LT-HSC quiescence. This suggests that Skp2 regulates stem cell pool and quiescence in a cell autonomous manner. We also showed that the colony-forming ability of BM cells from Skp2−/− donor was greater than those from WT transplantation (Figure 3F).

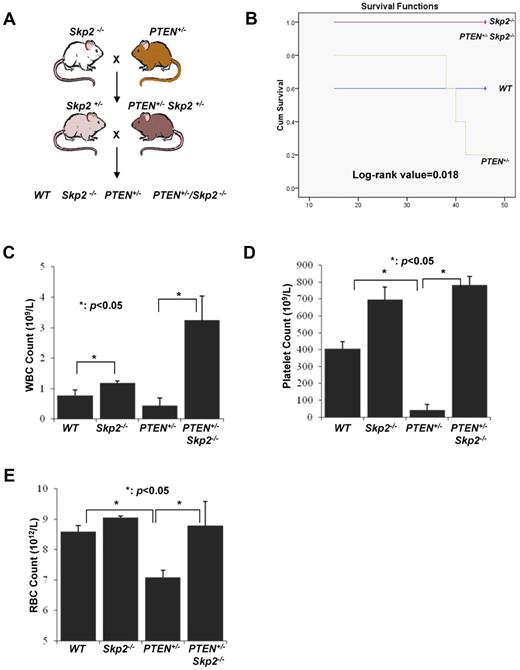

Loss of Skp2 rescues the failure of BM repopulation caused by PTEN deficiency

Earlier studies have shown that, although PTEN deletion promotes the early expansion of HSC pools, these HSCs exhaust quickly and thus are unable to stably reconstitute in lethally irradiated mice.4,5 We have recently demonstrated that Skp2 is a critical downstream effector for tumorigenesis on PTEN inactivation and that Skp2 deficiency markedly restricts cancer development on PTEN inactivation.13 We next determined whether Skp2 is responsible for the functional defects of HSCs on PTEN inactivation. To this end, we generated WT, PTEN+/−, and PTEN+/−Skp2−/− cohort mice by crossing Skp2−/− with PTEN+/− mice and isolated BM cells from these mice for serial BM transplantation (Figure 4A). As expected, PTEN inactivation reduced BM long-term reconstitution ability and mice survival compared with their WT counterparts (Figure 4B-E), which is consistent with previous reports.4,5 Notably, Skp2 deficiency completely rescued the defect in the BM reconstitution ability and mice survival on PTEN inactivation (Figure 4B-E). It should also be noted that Skp2 deficiency alone enhanced long-term reconstitution ability of HSCs compared with their WT counterparts (Figure 4C-E). The log-rank value of 0.018 was obtained with the Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of the fourth round transplantation among 4 different groups (Figure 4B). Our results therefore suggest that Skp2 is a crucial downstream effector responsible for HSC exhaustion on PTEN inactivation.

Skp2 deficiency rescues the BM defect in long-term reconstitution on PTEN inactivation. (A) The breeding strategy for WT, PTEN+/−, PTEN+/−Skp2−/−, and Skp2−/− mice. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of cumulative survival of the recipient mice after the fourth round of transplantation with WT, PTEN+/−, PTEN+/−Skp2−/−, and Skp2−/− BM cells (log-rank value = 0.018; n = 5). (C-E) The CBC test was performed to determine the number of WBCs (C), platelets (D), and RBCs (E) from the recipient mice after the fourth round of BM transplantation (*P < .05; n = 5).

Skp2 deficiency rescues the BM defect in long-term reconstitution on PTEN inactivation. (A) The breeding strategy for WT, PTEN+/−, PTEN+/−Skp2−/−, and Skp2−/− mice. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot analysis of cumulative survival of the recipient mice after the fourth round of transplantation with WT, PTEN+/−, PTEN+/−Skp2−/−, and Skp2−/− BM cells (log-rank value = 0.018; n = 5). (C-E) The CBC test was performed to determine the number of WBCs (C), platelets (D), and RBCs (E) from the recipient mice after the fourth round of BM transplantation (*P < .05; n = 5).

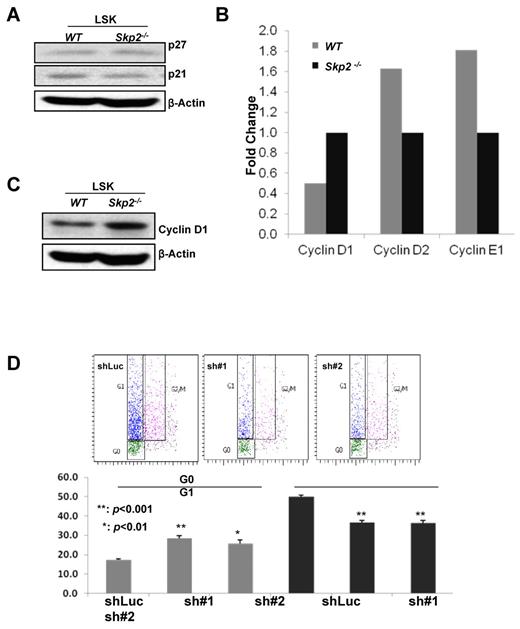

Cyclin D1 transcription and protein level are elevated in Skp2-deficient HSCs

Having shown that Skp2 plays an important role in HSC quiescence, pool size, and self-renewal, we next determined the molecular mechanism through which Skp2 regulates these processes. Because Skp2 is an E3 ligase component of the Skp2 SCF complex, which promotes cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis by targeting p27 and p21 for ubiquitination and degradation, we investigated the potential role of Skp2 in the regulation of p21 and p27 degradation in HSCs. Unexpectedly, there was no change in p21 and p27 protein expression in WT and Skp2−/− cultured LSK cells (Figure 5A), suggesting that p21 and p27 degradation is not involved in Skp2-mediated HSC functions. To confirm this result, we obtained freshly sorted LSK cells from 3 mice for Western blot analysis and found that p27 protein levels were comparable between WT and Skp2-deficient LSK cells (supplemental Figure 8). However, because of the limitation of cell number, we did not detect p21 protein signal in either WT or Skp2-deficient LSK cells (supplemental Figure 8).

Skp2 deficiency leads to elevated Cyclin D1 transcription and expression, in turn contributing to an increase in HSC cycling. (A) Western blot analysis of p27 and p21 protein expressions in cultured LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA level of various Cyclin family genes in LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice. (C) Western blot analysis of Cyclin D1 protein expression in LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice. (D) The G1 and G0 phases of LSK cells isolated from BM cells of Skp2−/− mice on Cyclin D1 knockdown were determined by flow cytometric analysis (**P < .001 and *P < .01; n = 3).

Skp2 deficiency leads to elevated Cyclin D1 transcription and expression, in turn contributing to an increase in HSC cycling. (A) Western blot analysis of p27 and p21 protein expressions in cultured LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA level of various Cyclin family genes in LT-HSCs from WT and Skp2−/− mice. (C) Western blot analysis of Cyclin D1 protein expression in LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice. (D) The G1 and G0 phases of LSK cells isolated from BM cells of Skp2−/− mice on Cyclin D1 knockdown were determined by flow cytometric analysis (**P < .001 and *P < .01; n = 3).

Cyclin family proteins, such as Cyclin D and Cyclin E, form complexes with CDK4 and CDK6 to regulate cell cycle entry. Because Skp2 is critical for HSC quiescence and self-renewal, it is highly possible that Skp2 may regulate the expression of these genes in HSCs. To test this hypothesis, we performed real-time PCR to determine the transcription levels of these genes in WT and Skp2-deficient HSCs. Notably, we found that the transcriptional level of Cyclin D1, but not Cyclin D2 and Cycle E2, was significantly increased in Skp2-deficient LT-HSCs compared with WT LT-HSCs (Figure 5B). Likewise, Cyclin D1 protein expression was also markedly up-regulated in Skp2−/− LSK cells (Figure 5C).

We next tested whether Cyclin D1 up-regulation is responsible for the reduction in quiescence of HSCs on Skp2 loss. We used lentiviral shRNA to knockdown Cyclin D1 in MEF cells and found that 2 shRNAs efficiently knocked down Cyclin D1 expression (supplemental Figure 9). We then knocked down Cyclin D1 expression in BM cells isolated from Skp2−/− mice, and G1 and G0 distribution of Skp2-deficient LSK cells was examined. Strikingly, Cyclin D1 knockdown remarkably enhanced the G0 population of Skp2−/− LSK cells, whereas the G1 population was reduced significantly (P < .01 and P < .001; Figure 5D), indicating that up-regulated Cyclin D1 contributes to the enhancement of HSC cycling on Skp2 deficiency. Collectively, our results suggest that up-regulated Cyclin D1 expression may provide a molecular explanation as to why Skp2 deficiency promotes HSC cycling, proliferation, and long-term reconstitution ability.

Loss of Skp2 sensitizes LSK and leukemia cells to chemotherapy agents

Cancer stem cells (CSCs, also known as cancer initiation cells) recently have emerged as important players in cancer initiation, progression, and relapse after therapy.26,27 CSCs display characteristics similar to those of normal stem cells, including the ability for self-renewal and to differentiate. Because CSCs normally stay in the quiescent stage and are resistant to current cancer therapy,26 finding ways to prompt quiescent CSCs to reenter cycling stages will sensitize CSCs to current chemotherapy agents. Because we have shown that Skp2 plays a critical role in maintaining HSCs in the quiescent stage and its deficiency promotes HSC cycling, we reasoned that Skp2 deficiency may sensitize LSK cells and CSCs to common chemotherapy agents. In support of this notion, we found that Skp2 deficiency significantly promoted apoptosis of cultured LSK cells on the treatment of chemotherapy agents, such as CPA, 5-FU, and DOX (Figure 6A). Consistent with the result from cultured LSK cells, the freshly sorted LSK cells from Skp2−/− mice displayed higher sensitivity to these chemotherapy agents compared with those from WT mice (P < .001; Figure 6B). Moreover, in vivo apoptosis assay by injecting 5-FU to mice showed that Skp2-deficient LSK cells exhibited a higher apoptosis rate than those from WT mice (61.34% ± 5.89% vs 45.09% ± 2.75%; P < .001; Figure 6C).

Loss of Skp2 sensitizes the cells to chemotherapeutic reagents. (A) Apoptosis rate of cultured LSK cells was measured by flow cytometry after treatment with CPA, 5-FU, and DOX, (*P < .05; n = 4). (B) Apoptosis rate of freshly sorted LSK cells was measured by flow cytometry after treatment with CPA, 5-FU, and DOX (**P < .001; n = 3). (C) In vivo apoptosis rate of LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice intraperitoneally injected with 5-FU was measured by flow cytometry, 61.34% ± 5.89% in Skp2−/− LSK cells versus 45.09% ± 2.75% in WT LSK cells (**P < .001; n = 3). (D) Validation of Skp2 shRNA knockdown efficiency. K562 were infected with lentiviral shRNAs against GFP control and Skp2, selected, and cell lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (E) Apoptosis rate of K562 cells with GFP or Skp2 knockdown were detected by flow cytometry after treatment with CPA and 5-FU (*P < .05; n = 4). (F) The hypothetical model for the role of Skp2 in HSC functions.

Loss of Skp2 sensitizes the cells to chemotherapeutic reagents. (A) Apoptosis rate of cultured LSK cells was measured by flow cytometry after treatment with CPA, 5-FU, and DOX, (*P < .05; n = 4). (B) Apoptosis rate of freshly sorted LSK cells was measured by flow cytometry after treatment with CPA, 5-FU, and DOX (**P < .001; n = 3). (C) In vivo apoptosis rate of LSK cells from WT and Skp2−/− mice intraperitoneally injected with 5-FU was measured by flow cytometry, 61.34% ± 5.89% in Skp2−/− LSK cells versus 45.09% ± 2.75% in WT LSK cells (**P < .001; n = 3). (D) Validation of Skp2 shRNA knockdown efficiency. K562 were infected with lentiviral shRNAs against GFP control and Skp2, selected, and cell lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. (E) Apoptosis rate of K562 cells with GFP or Skp2 knockdown were detected by flow cytometry after treatment with CPA and 5-FU (*P < .05; n = 4). (F) The hypothetical model for the role of Skp2 in HSC functions.

We next determined whether Skp2 deficiency also sensitizes leukemia cells to chemotherapy agents. To this end, we knocked down Skp2 in K562 leukemia cells, which overexpress the BCR-ABL oncogene, and assessed the apoptotic rates of these cells on the treatment of the chemotherapy agents. Notably, we found that Skp2 knockdown profoundly enhanced apoptosis in K562 cells on the treatment of CPA and 5-FU (Figure 6D-E). Similar results were also obtained in KBM5 leukemia cell line with BCR-ABL overexpression (supplemental Figure 10). These results confirm that Skp2 targeting may sensitize LSK and leukemia cells to chemotherapy reagents.

Discussion

The maintenance of HSC quiescence regulates HSC pool and self-renewal capabilities. How HSCs quiescence is regulated remains largely unclear. In this study we provide convincing evidence that Skp2 is a novel and critical regulator for HSC quiescence and self-renewal ability. Mechanistically, we found that, although Skp2 does not regulate p21 and p27 expressions, it regulates Cyclin D1 expression, in turn promoting cell cycle entry and proliferation.

Skp2, an important component of the Skp2 SCF complex, is shown to promote cell cycle entry by targeting p21 and p27 degradation. Skp2 deficiency in MEFs and cancer cells reduces cell cycle entry and cell proliferation but enhances apoptosis through p27 and p21 accumulation.6-8 However, loss of Skp2 in HSCs does not affect the rate of apoptosis but surprisingly promotes cell cycle entry and cell proliferation, in turn enhancing HSC pool, proliferation, and reconstitution ability through a mechanism independent of p21 and p27 degradation. This novel discovery strikingly contrasts our current understanding of the role of Skp2 in positively regulating cell cycle progression in normal differentiated and cancerous cells. Our study therefore shows a novel role of Skp2 as a cell cycle inhibitor in HSCs.

Cyclin D1 expression is regulated through transcriptional regulation and posttranslational modification. β-catenin is known to be a critical factor for Cyclin D1 gene expression, whereas glycogen synthase kinase-3–mediated Cyclin D1 phosphorylation has been shown to target Cyclin D1 for ubiquitination and degradation.28-31 Our findings show that Skp2-deficient HSCs display higher Cyclin D1 mRNA and protein levels, which contribute to the enhancement of HSC cycling and proliferation on Skp2 deficiency. Thus, Skp2 is a novel negative regulator for Cyclin D1 gene expression in HSCs. Because we have previously found that Skp2 cooperates with Myc and Miz1 transcription factors to induce RhoA gene expression important for cancer metastasis,20 it is possible that Skp2 may work in conjunction with Myc and Miz1 to regulate Cyclin D1 gene expression. Alternatively, Skp2 may antagonize β-catenin–mediated Cyclin D1 gene expression. Interestingly, the earlier study shows that inhibition of RhoA activity in HSCs increases Cyclin D1 levels, accompanied by the enhancement of HSC proliferation and self-renewal ability,32 similar to the HSC phenotypes observed on Skp2 deficiency. Thus, it is also probable that Skp2 may regulate RhoA level and activity to regulate Cyclin D1 expression and HSC phenotypes.

PTEN inactivation in HSCs causes the long-term exhaustion of HSC pool and the failure of reconstitution ability, which is correlated with hyper mTOR activity. Rapamycin treatment rescues the defects of HSC phenotypes on PTEN inactivation,5 indicating that mTOR serves as a critical downstream effector for HSC exhaustion on PTEN inactivation. Notably, we found that Skp2 deficiency also rescues the defect in long-term reconstitution ability of HSCs on PTEN inactivation, suggesting that Skp2 is also a critical downstream effector for HSC exhaustion. Because mTOR and Skp2 are both downstream effectors executing HSC exhaustion on PTEN inactivation,5 it is highly possible that mTOR may regulate Skp2 expression and activity or vice versa to control HSC functions on PTEN inactivation. A previous study showed that rapamycin treatment down-regulates Skp2 gene and protein expression in breast cancer cells,33 suggesting that mTOR can regulate Skp2 gene expression in cancer cells. It will be interesting to see whether rapamycin also down-regulates Skp2 levels in HSC on PTEN inactivation.

During the course of revising our manuscript, a recent study from Carlesso's group (Rodriguez et al34 ) showed that Skp2−/− mice display a higher frequency of LSK cells and GMPs, consistent with our current results. However, in contrast to our study, they showed that Skp2 deficiency enhanced quiescence and impaired long-term reconstitution ability of HSCs. Different from our data, Carlesso's group (Rodriguez et al34 ) showed that Skp2−/− BM cells exhibited elevated levels of cell cycle inhibitors such as p21 and p27. Although the reasons for such discrepancies remain to be further determined, the distinct genetic backgrounds of the mice used in these studies may have caused the differences. The mice used in our study were 129 and C57/B6 mixed background, whereas the mice used in their study had been backcrossed to B6 mice for 6 generations. Moreover, cell lineages and populations used in these 2 studies for quiescence and proliferation assay were different. In our study, we used LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, and LSK cells, whereas they used Lin− cells for quiescence and proliferation analysis. Thus, our study directly addresses the function of HSCs, whereas their study may not have.

With regard to the serial transplantation assay, they performed 2 rounds of transplantation and found that the reconstitution of WBCs from Skp2−/− donor BM 12 weeks after transplantation was reduced compared with WT donor cells. This result contradicts with the finding from their study and ours showing that HSC populations were higher in Skp2−/− mice than in WT mice. This finding is also hard to reconcile with the fact that hematopoiesis of Skp2−/− mice is completely normal compared with that in WT mice. Whether the mice survival after transplantation in their study was affected on Skp2 deficiency remains unclear. In our study, we did not find any difference in the first 2 rounds of the transplantation as determined by the CBC test, and mice survived 4 weeks after transplantation. However, we did find the long-term reconstitution ability of Skp2−/− BM cells after the fourth and fifth rounds of the transplantation was better than that of WT BM cells, consistent with the finding that HSC populations in Skp2−/− mice are higher than those in WT mice. Moreover, we also confirmed this notion with the in vivo competition assay.

The difference in p27 and p21 expressions between 2 studies may have been because of the distinct cell lineages used in these studies. In our study, we isolated both freshly sorted and cultured LSK cells for Western blot analysis, whereas they used total BM cells. Thus, our study may be more accurate to address the mechanistic insight for HSCs. Nevertheless, these 2 studies both underscore the important role of Skp2 in the regulation of HSC pool size, and future research will be required to further resolve the discrepancies between these 2 studies.

On the basis of our results, we propose a working model to explain how Skp2 regulates HSC functions (Figure 6F). Skp2 negatively regulates Cyclin D1 gene expression in HSCs, which may be responsible for the role of Skp2 in the maintenance of HSC quiescence, pool size, and self-renewal capability. Our study identifies Skp2 as a critical regulator for HSC quiescence and self-renewal capability and provides a novel paradigm for HSCs. Our finding that Skp2 deficiency increases the sensitivity of HSCs and CML cells to chemotherapy agents and promotes the long-term HSC reconstitution ability suggests that Skp2 targeting can be considered as an attractive therapeutic approach to enhance BM transplantation efficiency and the response of cancer cells and/or CSCs to the chemotherapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Pier Paolo Pandolfi, Keiichi Nakayama, and Xin Lin for the mice and cells. Special thanks is extended to Drs Wendy Schober, Karen C. Dwyer, and Zheng-bo Han for their assistance in flow cytometric analysis. They also thank the microarray core facility at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

This study was supported by M. D. Anderson Research trust fund and National Institutes of Health RO1 grants (H.K.L.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J. Wang designed and performed research experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; J. Wang, F.H., J. Wu, S.-W.L., C.-H.C., C.-Y.W., W.-L.Y., X.Z., and Y.S.J. performed experiments; Y.G. and A.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript; F.S. and P.H, provided cells and reagents; Q. L. and Y.-X.Z. provided kindly suggestions to the research; and H.-K.L. conceived the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hui-Kuan Lin, Department of Molecular and Cellular Oncology, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Unit 108, Y7.6079, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: hklin@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

J. Wang and F.H. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal