The cardiovascular protective effect of aspirin is ascribed to its ability to irreversibly inactivate cyclo-oxygenase (COX)–1 and consequently suppress platelet thromboxane A2 (TXA2) synthesis. Despite a short circulation half-life (∼ 20 minutes), the biologic effect of a single aspirin dose in healthy subjects lasts for approximately 3 days because of the time needed by aspirin-naive megakaryocytes to replenish the body with new platelets; the daily platelet regeneration rate is estimated at 10%. In vivo aspirin effect is gauged by a number of biochemical and functional assays, including measurements of serum TXB2 (the more stable but inactive metabolite of TXA2) and antiplatelet aggregation response to aspirin. However, it is important to recognize the limitations and inconsistency of such assays in accurately depicting in vivo aspirin effect.

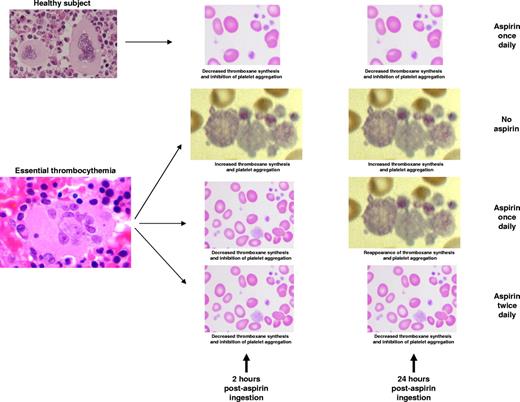

In vivo aspirin effect at peak and trough time points in healthy subjects and in patients with essential thrombocythemia receiving aspirin once or twice daily.

In vivo aspirin effect at peak and trough time points in healthy subjects and in patients with essential thrombocythemia receiving aspirin once or twice daily.

In healthy, nonsmoking subjects, once-daily aspirin produces > 95% suppression of both serum TXB2 and platelet aggregation and this effect lasts for at least 24 hours.2 This is, however, not necessarily the case in certain conditions where aspirin-induced inhibition of platelet function at 24 hours is incomplete (see figure).3,4 The concept of such “aspirin resistance” is not new and has been attributed primarily to increased platelet turnover with reappearance of new platelets with intact COX-1.5 Increased platelet turnover might result from either abnormal megakaryopoiesis (eg, ET) or increased peripheral consumption by injured blood vessels, as might be the case with diabetes mellitus (DM), coronary artery disease, or tobacco use.3,6 Either way, suboptimal 24-hour durability of aspirin effect has been associated with increased risk of arterial events7 and calls for new treatment approaches to overcome the particular phenomenon.

In a carefully selected group of nondiabetic ET patients not receiving other antiplatelet drugs, Pascale et al report that twice-daily enteric-coated aspirin at 100 mg dose was superior to once-daily enteric-coated aspirin at 200 mg dose, which was in turn superior to once-daily plain or enteric-coated aspirin at 100 mg dose, in favorably modifying residual thromboxane activity in “aspirin resistant” cases; the latter were defined as displaying ≥ 4 ng/mL of serum TXB2 at 24 hours after aspirin intake and constituted 78% of screened patients.1 There was no difference in the antiplatelet effect of enteric-coated versus plain aspirin at equal doses, which is consistent with previous observations.8 The biochemical evidence of improved aspirin effect by dose and schedule modification was also apparent by some but not other platelet function assays. The authors also showed that immature (ie, reticulated) platelet count was the sole predictor of adequate 24-hour suppression of thromboxane synthesis.

Although the potential merit of twice-daily aspirin dosing has also been suggested in patients with DM,9 it is particularly appealing in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) because (1) abnormal megakaryopoiesis and increased platelet production are integral components of the disease phenotype, (2) some of the risk factors for arterial thrombosis in MPN (eg, advanced age, angiopathy, leukocytosis, JAK2V617F, DM, smoking) have also been associated with aspirin resistance or increased immature platelet count, and (3) aspirin is a key component of treatment in MPN with level “A” evidence of value, at least in polycythemia vera.10 Accordingly, it is reasonable to consider the possibility that aspirin resistance contributes to treatment resistance in some MPN patients with microvascular symptoms and to the residual risk of thrombosis in otherwise adequately treated cases.

The concept of twice-daily aspirin therapy is potentially practice-changing but requires additional controlled studies to determine the clinical relevance of reversing biochemical resistance to aspirin and safety of twice-daily dosing, especially in terms of long-term bleeding risk. In the context of MPN, one has to also dissect the confounding effect of cytoreductive therapy, which is known to markedly suppress platelet turnover and therefore possibly attenuate aspirin resistance. For now, it would be premature to indiscriminately order platelet function tests looking for aspirin resistance and place patients on a twice-daily aspirin regimen wishing for a better clinical outcome. Such measures should be reserved for those patients with clear evidence of treatment failure.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■