Leaving the safety of home exposes our vulnerabilities. In this issue of Blood, Uy and coauthors explore the clinical benefit of interrupting the protective niches in which leukemia cells live in an effort to enhance the benefit of chemotherapy in treating patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1

Hematopoietic cells express a wide range of adhesion molecules (CXCR4, very late antigen-4, c-kit [CD117], L-selectin [CD62L], and CD44) and marrow stroma express their corresponding ligands: stromal cell–derived factor 1α (SDF-1α), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, kit ligand, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1, and hyaluronic acid. Hematopoietic cells leave home, or are mobilized from the bone marrow to the blood, as a result of cytokine-induced changes in adhesion molecules expressed on their surface and/or their corresponding ligands on bone marrow cells.

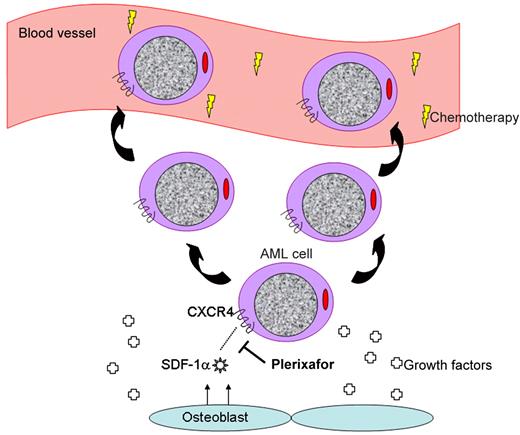

Plerixafor interrupts the CXCR4/SDF-1α interaction, mobilizing leukemia cells to the peripheral blood.

Plerixafor interrupts the CXCR4/SDF-1α interaction, mobilizing leukemia cells to the peripheral blood.

Of these molecular pairs, the most highly characterized and possibly important is the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand SDF-1α.2 This duo may be thought of as a molecular tether responsible for sequestering hematopoietic cells in their cellular niches where they may happily grow and divide. Interrupting this tether using plerixafor,3 a small molecule antagonist of CXCR4, results in mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells to the peripheral blood stream where they may be harvested for the purpose of stem cell transplantation. Treatment with G-CSF similarly mobilizes bone marrow cells via the cell surface peptidase CD26 that cleaves SDF-1α, among other mechanisms.4

It is no surprise that the same molecular interactions used to retain normal hematopoietic cells in the marrow are similarly used by leukemia cells (see figure).5 Interrupting the CXCR4/SDF-1α axis results in increased chemosensitization of AML cells as demonstrated both in vitro6,7 and in vivo.8 Thus, using agents capable of disengaging AML cells from their niche in combination with standard chemotherapeutic agents represents a novel approach to increase the exposure of leukemia cells to chemotherapy, displace them from protective niches providing growth factors, and improve on existing treatments for patients with AML.

In their phase 1/2 study, Uy and his co-investigators treated 52 patients with relapsed and refractory AML using a standard regimen containing mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cy-tarabine (MEC) in combination with plerixafor. Plerixafor appeared well tolerated in this regimen, did not result in symptomatic hyperleukocytosis or delayed blood count recovery, and the combination resulted in an encouraging remission frequency in this traditionally difficult-to-treat patient population (complete remission = 39%). The authors identified that both leukocytes and leukemia blast cells were mobilized within hours of plerixafor and that both normal and leukemia cells underwent mobilization at an equal frequency (ie, leukemia cells were not preferentially mobilized over normal hematopoietic cells).

Conceptually, this study is very important for the field of AML and for all cancers. Clinical oncology has done what possible to maximize cytotoxic therapies directed at cancer cells and next-generation sequencing will help sort out the cell-intrinsic molecular lesions that may lead to new imatinib-style therapies. But, let's not forget about the neighborhood. That tumors cleverly alter their own environment by recruiting their own vasculature has led to therapies such as bevacizumab.9 And, clinging tightly to a protective home as leukemia cells do likely represents another front we must conquer to improve clinical success. Indeed, increased CXCR4 expression on human AML cells is associated with inferior prognosis.10

Whether plerixafor is an effective agent by which to accomplish this in AML will require a phase 3 study in which patients will be randomized to treatment with placebo versus plerixafor in combination with induction and consolidation chemotherapy. A statistically significant survival benefit in the plerixafor arm will indicate that this strategy is successful. The challenges to accomplishing this goal involve the fact that both leukemia cells and normal hematopoietic cells rely on CXCR4/SDF-1α. Indeed, the authors observed that both normal and leukemia cells were mobilized at equal ratios, indicating that plerixafor is not selective. And how reliant on the microenvironment are leukemia cells anyway? Just as cancer cells in vitro are less reliant on growth factors and stroma than their normal counterparts, will dislodging leukemia cells from their niche during treatment make a difference? Alternatively, could it be that another molecular pair retaining leukemia cells in their niche, perhaps one listed above, may be more critical for targeting? From the standpoint of safety, the authors show that normal blood count recovery is not delayed in patients treated with this combination. Therefore, increased chemotoxicity to normal hematopoietic cells does not appear to be the case, at least not after 1 cycle of treatment. Will subsequent cycles of treatment with plerixafor and chemotherapy result in toxicity to normal marrow?

Although many questions remain, Uy and colleagues provide an excellent first example of how to make leukemia get out. Now we need to make it stay out.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal