Abstract

Genomic disorders affecting the genes encoding factor H (fH) and the 5 factor H related proteins have been described in association with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. These include deletions of CFHR3, CFHR1, and CFHR4 in association with fH autoantibodies and the formation of a hybrid CFH/CFHR1 gene. These occur through nonallelic homologous recombination secondary to the presence of large segmental duplications (macrohomology) in this region. Using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification to screen for such genomic disorders, we have identified a large atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome family where a deletion has occurred through microhomology-mediated end joining rather than nonallelic homologous recombination. In the 3 affected persons of this family, we have shown that the deletion results in formation of a CFH/CFHR3 gene. We have shown that the protein product of this is a 24 SCR protein that is secreted with normal fluid-phase activity but marked loss of complement regulation at cell surfaces despite increased heparin binding. In this study, we have therefore shown that microhomology in this area of chromosome 1 predisposes to disease associated genomic disorders and that the complement regulatory function of fH at the cell surface is critically dependent on the structural integrity of the whole molecule.

Introduction

Complement genes within the Regulators of Complement Activation cluster at chromosome 1q32 are arranged in tandem within 2 groups.1 In a centromeric 360-kb segment lie the genes for factor H (fH; CFH; OMIM 134370) and 5 fH-related proteins: CFHR1 (OMIM 134371), CFHR2 (OMIM 600889), CFHR3 (OMIM 605336), CFHR4 (OMIM 605337), and CFHR5 (OMIM 608593). Sequence analysis of this region shows evidence of several large genomic duplications, also known as low copy repeats, resulting in a high degree of sequence identity between CFH and the genes for the 5 fH-related proteins.2–4 The secreted protein products of these genes are similar in that they consist of repetitive units (∼ 60 amino acids) named short consensus repeats (SCRs). Low copy repeats, such as those seen in the Regulators of Complement Activation cluster, are frequently associated with genomic rearrangements.5 These usually result from nonallelic homologous recombination (NAHR) between LCRs. We have previously shown, in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS; OMIM 235400), that NAHR in this region can lead to the formation of a hybrid gene consisting of the first 21 exons of CFH (encoding SCRs 1-18 of the hybrid gene) and the last 2 exons of CFHR1 (encoding SCRs 19 and 20 of the hybrid gene).6 This hybrid gene encodes a protein product that is identical to a functionally significant fH mutant (Ser1191Leu/Val1197Ala), which we have shown arises by gene conversion.7 We have also shown that NAHR in this region leads to deletions incorporating CFHR3/CFHR1 and CFHR1/CFHR4, which are associated with the presence of fH autoantibodies in aHUS.8–10 We routinely use multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA)11 to screen for genomic disorders in aHUS. In this study, we report the finding of a deletion in the C terminal region of CFH in a large aHUS family. Microhomology in the sequence flanking the breakpoint suggests that the deletion has occurred through microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ)12 and not NAHR. The deletion results in a hybrid gene that derives its N terminal exons from CFH and its C terminal exons from CFHR3. Functional analyses indicate that, while functional in the fluid phase, the hybrid protein is defective in its ability to control complement on cell surfaces despite increased heparin binding.

Methods

Subjects

The study was approved by the Northern and Yorkshire Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Family details

In this family, there are 3 affected persons. III:6 was the first to present at the age of 44 years (Figure 1; Table 1). He initially complained of headache, blurred vision, and shortness of breath. There was no history of a preceding diarrheal illness. On examination, he was found to be hypertensive with signs in his cardiovascular system compatible with congestive cardiac failure. Initial investigations showed acute renal failure, thrombocytopenia, and a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Lactate dehydrogenase was elevated and haptoglobins were absent. A clinical diagnosis of aHUS was made, and he was treated with daily plasma exchange for 5 days. Despite this, there was no improvement in renal function and hemodialysis was commenced. A renal biopsy showed evidence of a thrombotic microangiopathy. He was discharged from hospital on regular hemodialysis. Nine months later, he received a cadaveric renal transplant. Immunosuppression consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisolone. Initial transplant function was good, but at one month after surgery he had an episode of acute cellular rejection, which responded to steroids. At 6 months after transplantation, he developed recurrent HUS complicated by a myocardial infarct and the development of an ischemic cardiomyopathy. Despite changing from tacrolimus to rapamycin, the allograft did not recover and he underwent a transplant nephrectomy. He returned to hemodialysis and subsequently died of congestive cardiac failure 8 years later.

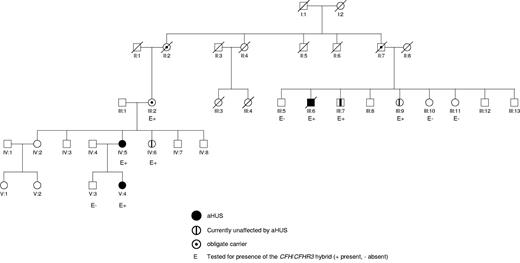

Pedigree of the family. This shows that there are 3 members of the family who have been affected by aHUS (III:6, IV:5, and V:4) and 4 members of the family (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6) who are unaffected but carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene.

Pedigree of the family. This shows that there are 3 members of the family who have been affected by aHUS (III:6, IV:5, and V:4) and 4 members of the family (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6) who are unaffected but carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene.

Details of the affected persons (III:6, IV:5, and V:4) and the unaffected carriers (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6) of the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene

| Patient ID . | Age at presentation . | Sex . | Clinical outcome . | Length of follow-up, y . | Transplanted . | C3, g/L . | C4, g/L . | Factor H, g/L . | Factor I, mg/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III:6 | 44 y | Male | ESRF | 11 | Yes recurrence | 0.86 | 0.36 | 0.70 | 63 |

| IV:5 | 25 y | Female | ESRF | 3 | No | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.59 | 67 |

| V:4 | 9 mo | Female | Recovered renal function, PE×1/2 weeks | 2 | No | 0.96 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 49 |

| III:2 | Female | 1.67 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 78 | ||||

| III:7 | Male | 1.29 | 0.22 | 0.66 | 79 | ||||

| III:9 | Female | 1.61 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 81 | ||||

| IV:6 | Female | 1.76 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 76 |

| Patient ID . | Age at presentation . | Sex . | Clinical outcome . | Length of follow-up, y . | Transplanted . | C3, g/L . | C4, g/L . | Factor H, g/L . | Factor I, mg/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III:6 | 44 y | Male | ESRF | 11 | Yes recurrence | 0.86 | 0.36 | 0.70 | 63 |

| IV:5 | 25 y | Female | ESRF | 3 | No | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.59 | 67 |

| V:4 | 9 mo | Female | Recovered renal function, PE×1/2 weeks | 2 | No | 0.96 | 0.15 | 0.45 | 49 |

| III:2 | Female | 1.67 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 78 | ||||

| III:7 | Male | 1.29 | 0.22 | 0.66 | 79 | ||||

| III:9 | Female | 1.61 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 81 | ||||

| IV:6 | Female | 1.76 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 76 |

ESRF indicates end-stage renal failure; and PE, plasma exchange.

IV:5 was the next to present at the age of 25. At 31 weeks of pregnancy, she developed severe pre-eclampsia and underwent a cesarean section. Her plasma creatinine rose during the last trimester from a baseline of 74 μmol/L to 209 μmol/L on the day of the section. One year previously, she had delivered a male infant, again by cesarean section undertaken in response to worsening pre-eclampsia. After the delivery of her second child, her renal function continued to deteriorate requiring hemodialysis. Other than fragmentation on a blood film and an elevated lactate dehydrogenase of 514 U/L (normal, 50-150 U/L), there was no overt evidence of aHUS. A renal biopsy, however, showed subtle signs of a thrombotic microangiopathy in combination with acute tubular necrosis. There was no recovery of renal function, and she has subsequently transferred to peritoneal dialysis.

V:4 presented at 9 months with heavy proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and a lactate dehydrogenase of 5000 U/L. Her creatinine at presentation was marginally elevated. She was commenced on plasma exchange and has maintained her native renal function for more than 2 years with regular prophylactic plasma exchange.

The 2 obligate carriers II.2 and II.7 died at the ages of 82 and 81 years, respectively, without any history of renal disease.

Complement assays and fH autoantibody screening

C3 and C4 levels were measured by rate nephelometry (Beckman Array 360). fH and factor I (fI) levels were measured by radioimmunodiffusion (Binding Site). The normal ranges were C3 (0.68-1.38 g/L), C4 (0.18-0.60 g/L), fH (0.35-0.59 g/L), and fI (38-58 mg/L). Screening for fH autoantibodies was undertaken using ELISA as described previously.10

Mutation screening and genotyping

Mutation screening of CFH, CD46 (OMIM 120920), CFI (OMIM 217030), CFB (OMIM 138470), C3 (OMIM 120700), THBD (OMIM 188040), and CFHR5 was undertaken using direct fluorescent sequencing as described previously.13–17 Genotyping of the following SNPs was undertaken using direct sequencing: CD46 −652A > G (rs2796267), CD46 −366A > G (rs2796268), CD46 c.4070T > C (rs7144), CFH −331C > T (rs3753394), CFH c.184G > A Val62Ile (rs800292), CFH c.1204 C > T p.His402Tyr (rs1061170), CFH c.2016A > G p.Gln672Gln (rs3753396), and CFH c.2808G > T p.Glu936Asp (rs1065489).

Screening for genomic disorders

Screening for genomic disorders affecting CFH, CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, and CFHR5 was undertaken using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification11 (MLPA) in both the affected family and 505 normal controls. Details of the probes used are given in Table 2. These include those in a kit from from MRC Holland (www.mlpa.com; SALSA MLPA kit P236-A1 ARMD) and probes designed within our own laboratory for CFH exons 20, 22, and 23, which were analyzed in a separate in-house assay. The normal controls were composed of 405 DNA samples obtained from the Health Protection Agency Culture Collections (http://www.hpacultures.org.uk/products/dna/hrcdna) and 100 DNA samples obtained from local blood donors. The samples from the Health Protection Agency were also originally obtained from a control population of randomly selected, nonrelated United Kingdom white blood donors.

MLPA probes used to determine CFHR1 and CFHR3 copy number

| Probe no . | Gene, exon . | Ligation site . | Partial sequence (20 nt adjacent to ligation site) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CFH, exon 1 | 151-152 | TGCTACACAA-ATAGCCCATA |

| 2 | CFH, exon 2 | 226-227 | GGTCTGACCA-AACATATCCA |

| 3 | CFH, exon 3 | 389-390 | TCCTTTTGGT-ACTTTTACCC |

| 4 | CFH, exon 4 | 490-491 | ATTACCGTGA-ATGTGACACA |

| 5 | CFH, exon 6 | 850-851 | AAAGAGGAGA-TGCTGTATGC |

| 6 | CFH, exon 9 | 1310-1311 | AATCAAAATC-ATGGAAGAAA |

| 7 | CFH, exon 11 | Intron 10, 5429 nt before exon 11 | TAGGTAGTCA-TATTTGGAAC |

| 8 | CFH, exon 12 | Intron 12, 1079 nt after exon 12 | TGGACACATT-ATGATTGAGT |

| 9 | CFH, exon 13 | 1925-1926 | AGTTGGACCT-AATTCCGTTC |

| 10 | CFH, exon 15 | Intron 15, 863 nt after exon 15 | AGCTGAGTGA-CATGAGGTAG |

| 11 | CFH, exon 18 | 2751-2752 | GGAACCATTA-ATTCATCCAG |

| 12 | CFH, exon 20 | 3206-3207 | TCTGCTATTA-ATGCATGTTA |

| 13 | CFH, exon 22 | Intron 22 | ACTCATCACA-GAGATTTTTC |

| 14 | CFH, exon 23 | 3680-3681 | ACCTGTTCTC-GAATAAAGCT |

| 15 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 5 nt after exon 23 | TCAATACATA-AATGCACCAA |

| 16 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 286 nt after exon 23 | CACTTATACA-TGCAATCCGT |

| 17 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 8775 nt after exon 23 | AGTCCGAGGT-AGAAAGGGAC |

| 18 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 21 283 nt after exon 23 and 1354 nt before CFHR3 exon 1 | GTGGTAATCT-TGGCTCTCAG |

| 19 | CFHR3, exon 1 | Intron 1 | AGGTAAGTTA-AAAGAGATCT |

| 20 | CFHR3, exon 2 | Intron 1 | CATTTTCTTG-TGGAATTACA |

| 21 | CFHR3, exon 3 | Intron 3 | CGGACGACAG-TCTCAGACTT |

| 22 | CFHR3, exon 4 | Intron 4 | GGGTTATATG-AATTCCTACA |

| 23 | CFHR3, exon 6 | Intron 5 | TTCCCCAACA-TCACAGCAGA |

| 24 | CFHR3, exon 6 | 1003-1002 reverse | TCCCTTCCCG-ACACACTGCT |

| 25 | CFHR1, exon 1 | Intron 1 | GGATAATTCA-ATTGAAATGG |

| 26 | CFHR1, exon 3 | Intron 3 | AGAGTTTCAG-GTCCATGTGT |

| 27 | CFHR1, exon 5 | Intron 5 | AATCTGTGAT-TATTTTGTTA |

| 28 | CFHR1, exon 6 | 945-946 | CCTGTTCTCA-AATAAAAGCTT |

| 29 | CFHR1, exon 6 | 1246-1247 | TTTTCCAAGT-TTTAATATGG |

| 30 | CFHR2, exon 1 | Intron 1 | AACTATGTCT-TGGAGTTTCG |

| 31 | CFHR2, exon 2 | Intron 2 | AGATCATAAA-CACTTGATAA |

| 32 | CFHR2, exon 3 | Intron 3 | AATACCTGTG-TGTGGTTTAT |

| 33 | CFHR2, exon 4 | 589-590 | ATGCTCCAGG-TTCATCAGTT |

| 34 | CFHR5, exon 1 | 136-137 | TGGGTATCCA-CTGTTGGGGG |

| 35 | CFHR5, exon 2 | 207-208 | TGAAGAAGAT-TATAACCCTT |

| 36 | CFHR5, exon 3 | 398-399 | CTTCAGGACT-AATACATCTG |

| Probe no . | Gene, exon . | Ligation site . | Partial sequence (20 nt adjacent to ligation site) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CFH, exon 1 | 151-152 | TGCTACACAA-ATAGCCCATA |

| 2 | CFH, exon 2 | 226-227 | GGTCTGACCA-AACATATCCA |

| 3 | CFH, exon 3 | 389-390 | TCCTTTTGGT-ACTTTTACCC |

| 4 | CFH, exon 4 | 490-491 | ATTACCGTGA-ATGTGACACA |

| 5 | CFH, exon 6 | 850-851 | AAAGAGGAGA-TGCTGTATGC |

| 6 | CFH, exon 9 | 1310-1311 | AATCAAAATC-ATGGAAGAAA |

| 7 | CFH, exon 11 | Intron 10, 5429 nt before exon 11 | TAGGTAGTCA-TATTTGGAAC |

| 8 | CFH, exon 12 | Intron 12, 1079 nt after exon 12 | TGGACACATT-ATGATTGAGT |

| 9 | CFH, exon 13 | 1925-1926 | AGTTGGACCT-AATTCCGTTC |

| 10 | CFH, exon 15 | Intron 15, 863 nt after exon 15 | AGCTGAGTGA-CATGAGGTAG |

| 11 | CFH, exon 18 | 2751-2752 | GGAACCATTA-ATTCATCCAG |

| 12 | CFH, exon 20 | 3206-3207 | TCTGCTATTA-ATGCATGTTA |

| 13 | CFH, exon 22 | Intron 22 | ACTCATCACA-GAGATTTTTC |

| 14 | CFH, exon 23 | 3680-3681 | ACCTGTTCTC-GAATAAAGCT |

| 15 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 5 nt after exon 23 | TCAATACATA-AATGCACCAA |

| 16 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 286 nt after exon 23 | CACTTATACA-TGCAATCCGT |

| 17 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 8775 nt after exon 23 | AGTCCGAGGT-AGAAAGGGAC |

| 18 | CFH, exon 23 | Intron 23, 21 283 nt after exon 23 and 1354 nt before CFHR3 exon 1 | GTGGTAATCT-TGGCTCTCAG |

| 19 | CFHR3, exon 1 | Intron 1 | AGGTAAGTTA-AAAGAGATCT |

| 20 | CFHR3, exon 2 | Intron 1 | CATTTTCTTG-TGGAATTACA |

| 21 | CFHR3, exon 3 | Intron 3 | CGGACGACAG-TCTCAGACTT |

| 22 | CFHR3, exon 4 | Intron 4 | GGGTTATATG-AATTCCTACA |

| 23 | CFHR3, exon 6 | Intron 5 | TTCCCCAACA-TCACAGCAGA |

| 24 | CFHR3, exon 6 | 1003-1002 reverse | TCCCTTCCCG-ACACACTGCT |

| 25 | CFHR1, exon 1 | Intron 1 | GGATAATTCA-ATTGAAATGG |

| 26 | CFHR1, exon 3 | Intron 3 | AGAGTTTCAG-GTCCATGTGT |

| 27 | CFHR1, exon 5 | Intron 5 | AATCTGTGAT-TATTTTGTTA |

| 28 | CFHR1, exon 6 | 945-946 | CCTGTTCTCA-AATAAAAGCTT |

| 29 | CFHR1, exon 6 | 1246-1247 | TTTTCCAAGT-TTTAATATGG |

| 30 | CFHR2, exon 1 | Intron 1 | AACTATGTCT-TGGAGTTTCG |

| 31 | CFHR2, exon 2 | Intron 2 | AGATCATAAA-CACTTGATAA |

| 32 | CFHR2, exon 3 | Intron 3 | AATACCTGTG-TGTGGTTTAT |

| 33 | CFHR2, exon 4 | 589-590 | ATGCTCCAGG-TTCATCAGTT |

| 34 | CFHR5, exon 1 | 136-137 | TGGGTATCCA-CTGTTGGGGG |

| 35 | CFHR5, exon 2 | 207-208 | TGAAGAAGAT-TATAACCCTT |

| 36 | CFHR5, exon 3 | 398-399 | CTTCAGGACT-AATACATCTG |

Ligation sites refer to positions in Genbank reference sequences NM_000186.2 (CFH), NM_021023.3 (CFHR3), NM_002113.1 (CFHR1), NM_005666.2 (CFHR2), and NM_030787.1 (CFHR5). Probes 12 to 14 were designed in our laboratory. The remaining probes are from an MRC Holland (www.mlpa.com) kit (SALSA MLPA kit P236-A1 ARMD).

Reagents for the MLPA reaction were purchased from MRC-Holland. The ligation reactions were carried out according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol using 100-200 ng genomic DNA and 2-fmol probe. Incubations and PCR amplification were carried out on a DNA Engine Tetrad 2 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad); 1 μL of product and 0.5 μL ROX 500 internal size standard were made up to 10 μL using dH2O, and samples were run on the ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer capillary electrophoresis system (Applied Biosystems). Peak areas for each sample were determined using the proprietary GeneMarker software (Version 1.90) and dosage quotients calculated. A dosage quotient (probe ratio) of between 0.3 and 0.7 was taken to be indicative of a heterozygous deletion.

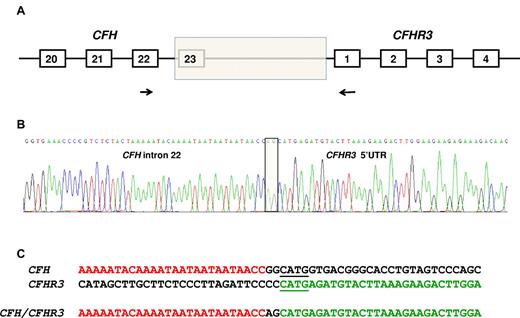

Identifying the breakpoint of the deletion

To identify the breakpoint of the deletion that resulted in the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene, genomic DNA was amplified using a forward primer specific for CFH in exon 22 and a reverse primer in exon 1 of CFHR3 (Figure 2A). The sequence of the forward primer was CAATGGTCAGAACCACCAAAAT, and the reverse was GAAACCCACAAGGTCAGAATGAC. The product (975 bp) was then sequenced using direct fluorescent sequencing.

Identification of the deletion breakpoint. (A) The breakpoint of the deletion (shaded box) was identified in genomic DNA using a forward primer (indicated by the forward arrow) in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer (indicated by the reverse arrow) in CFHR3 exon 1. (B) Sequence of the breakpoint. Two nucleotides (AG) interposing between CFH intron 22 sequence and CFHR3 5′-UTR sequence (shaded box). (C) CFH and CFHR3 sequence flanking the breakpoint. Microhomologous sequence adjacent to the breakpoint is underlined.

Identification of the deletion breakpoint. (A) The breakpoint of the deletion (shaded box) was identified in genomic DNA using a forward primer (indicated by the forward arrow) in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer (indicated by the reverse arrow) in CFHR3 exon 1. (B) Sequence of the breakpoint. Two nucleotides (AG) interposing between CFH intron 22 sequence and CFHR3 5′-UTR sequence (shaded box). (C) CFH and CFHR3 sequence flanking the breakpoint. Microhomologous sequence adjacent to the breakpoint is underlined.

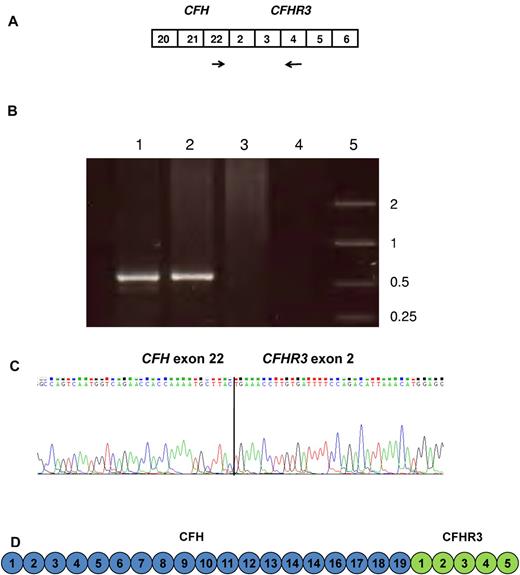

cDNA sequencing of a potential CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene

mRNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes of one affected member (IV:5). cDNA was prepared in a standard manner and then amplified using a forward primer in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer in CFHR3 exon 4 (Figure 3A). The sequence of the forward primer was CAATGGTCAGAACCACCAAAAT, and the reverse was CATCTGCTGTTGCATATCCTG. The product (520 bp), shown in Figure 3B, was then sequenced using direct fluorescent sequencing.

Identification of message from the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene. (A) Message for the hybrid CFH/CFHR3 gene was confirmed in cDNA using a forward primer (indicated by the forward arrow) in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer (indicated by the reverse arrow) in CFHR3 exon 4. (B) Gel showing amplified cDNA. Lanes 1 and 2 show cDNA from IV:5 and V:4 (both affected persons) amplified using a forward primer in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer in CFHR3 exon 4. Lane 3 shows normal control cDNA amplified with same primers. Lane 4 is a no DNA control. Lane 5 shows a size marker (kb). (C) cDNA sequence confirmed the presence of sequence consistent with a hybrid CFH/CFHR3 gene. (D) The protein product of the CFH/CFHR3 gene is a 24 SCR protein where SCRs 1 to 19 are derived from fH and SCRs 20 to 24 from CFHR3.

Identification of message from the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene. (A) Message for the hybrid CFH/CFHR3 gene was confirmed in cDNA using a forward primer (indicated by the forward arrow) in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer (indicated by the reverse arrow) in CFHR3 exon 4. (B) Gel showing amplified cDNA. Lanes 1 and 2 show cDNA from IV:5 and V:4 (both affected persons) amplified using a forward primer in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer in CFHR3 exon 4. Lane 3 shows normal control cDNA amplified with same primers. Lane 4 is a no DNA control. Lane 5 shows a size marker (kb). (C) cDNA sequence confirmed the presence of sequence consistent with a hybrid CFH/CFHR3 gene. (D) The protein product of the CFH/CFHR3 gene is a 24 SCR protein where SCRs 1 to 19 are derived from fH and SCRs 20 to 24 from CFHR3.

Western blotting

To screen for potential protein products arising from the deletion, sera were diluted 1/100 in solubilizing buffer and 10 μL electrophoresed on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and blocked with 5% dried milk/PBS. Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti–human fH monoclonal antibody 35H9 (kind gift from Santiago Rodriguez de Cordoba) in 5% dried milk/PBS. After washing 3 times in PBS/0.1% Tween 20, the blot was incubated with goat anti–mouse-Ig HRP (Stratech Scientific; 1/3000 in 5% dried milk/PBS). After 1 to 2 hours at room temperature, blots were washed twice with PBS/0.1% Tween 20 and with PBS only. Blots were then developed using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Scientific).

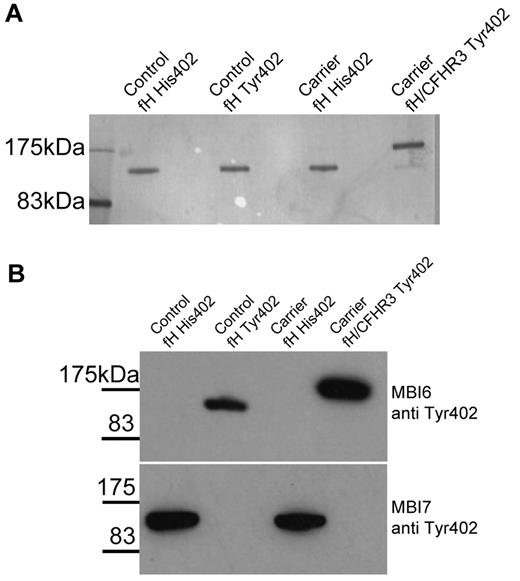

Monoclonal antibodies specific for the Tyr402 (MBI-6) and His402 (MBI-7) isoforms of fH were used both in Western blotting and a quantitative ELISA as described.18 Western blotting enabled the identification of the allele carrying the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene. The quantitative ELISA enabled an assessment of the differential protein concentration of mutant and wild-type fH. Total fH concentration was measured in the same assay using the mouse anti–human fH monoclonal antibody OX-24.18

Hemolytic assay

This was undertaken as previously described by Sánchez-Corral et al using normal human serum as a negative control,19 serum from an affected aHUS patient known to carry the CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene6 as a positive control, an affected person carrying the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene (IV:5), and 2 unaffected persons carrying the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene (III:2 and IV:6). Sheep red blood cells (TCS Biologicals) were washed several times in PBS and subsequently transferred to AP buffer (2.5mM barbital, 1.5mM sodium barbital, 144mM NaCl, 10mM EGTA, and 7mM MgCl, pH 7.4) for 2 further washes. Cells were resuspended at 0.1% and 100 μL plated out on round-bottomed 96-well plates containing 100 μL of triplicate serial dilutions of serum. A duplicate serum dilution was set up in alternative pathway buffer plus 50mM EDTA to act as blank. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 to 60 minutes before red cells were pelleted at 500g for 5 minutes. Absorbance of supernatant was measured at A410. The percentage lysis was calculated for each sample after the appropriate blank reading for each sample was subtracted, and this value was then divided by the A410 value obtained for total lysis of red cells in equivalent volume of dH20.

Separation and purification of fH isoforms

Genotyping of CFH c.1204C > T; p.His402Tyr (rs1061170) was undertaken in both affected persons and unaffected carriers. IV:6 (an unaffected carrier) was found to be heterozygous for this sequence variant and fresh EDTA plasma (40 mL) was obtained from her. The protein product (fH/CFHR3) of the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene was then separated and purified using affinity chromatography on an anti–fHY402 or anti–fHH402 column (mAb MBI-6 or MBI-7, in house; 1 mL HiTrap column; GE Healthcare; supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Eluted fH (His402) or fH/CFHR3 (Tyr402) hybrid proteins were applied to a Superdex 200 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) to remove aggregates and minor contaminants and to buffer exchange into AP buffer (5mM sodium barbitone, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 7mM MgCl2, 10mM EGTA) for functional assays. Identical procedures were carried out with plasma from a healthy control person also heterozygous for Tyr402His. Protein concentration was determined using an extinction coefficient of 1.9 cm−1(mg/mL)−1, a mass of fH of 155 kDa, and of the hybrid fH/CFHR3 protein of 186 kDa.

Surface plasmon resonance functional analyses

All analyses were carried out in a Biacore T100 (GE Healthcare) using 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 0.01% Surfactant P20 as running buffer; where convertase was generated buffer was supplemented with 1mM Mg2+. C3b was immobilized on a CM5 (Carboxymethyl) Biacore chip (GE Healthcare) using thioester coupling (1200 RU, see Figures 6A and 7C) or amine coupling (370 RU; see Figure 7D).20 Binding of fH or fH/CFHR3 to C3b was analyzed by flowing purified fH proteins over the thioester-coupled surface for 180 seconds at 30 μL/min. The surface was regenerated with 0.1M sodium citrate, pH 4, 1M NaCl. Cofactor activity was monitored on an identical surface by flowing fH (1 μg/mL) with fI (5 μg/mL; Comptech) for 2 × 40 seconds with regeneration after each incubation. The ability of surface-bound C3b to form convertase before and after fH/fI treatment was determined by flowing factor B and factor D across the surface for 150 seconds. Decay accelerating activity was assessed by forming convertase on an amine-coupled C3b surface (35 μg/mL factor B, 1 μg/mL factor D, 150 seconds), allowing to decay naturally for 160 seconds, then flowing fH or fH/CFHR3 over the surface (120 seconds) to visualize accelerated decay in real time. Background binding of fH protein to the surface was measured in the absence of Bb (the cleavage fragment of factor B) and subtracted from the sensorgram.

Regulator activity of fH/CFHR3 on cell surfaces

Proteins purified from the unaffected carrier and the control person were used in decay accelerating and cofactor assays as described previously.21 The unaffected carrier (IV:6) and the control person were both homozygous for the G allele of CFH c.184G > A; p.Val62Ile. In brief, to assess decay-accelerating activity, the AP convertase was formed on C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes (EAC3b) by incubating with factor B (purified in-house as described)20 and factor D (Comptech) for 15 minutes at 37°C. Convertase formation was stopped with EDTA, and cells were incubated with molar equivalents of fH or fH/FHR3 hybrid for 15 minutes at 25°C. Lysis was developed using serum depleted of fH and factor B (NHSΔBH) diluted in PBS/20mM EDTA. To determine the amount of lysis, cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and hemoglobin release was measured at 410 nm. Controls included 0% lysis (buffer only) and 100% lysis (0.1% Nonidet-P40), and the observed cell lysis was calculated as a percentage as previously described.21

To test cell-surface cofactor activity, EAC3b were mixed with molar equivalents of fH or fH/CFHR3 protein and constant fI (23nM; Comptech) for 8 minutes at 25°C. Cells were washed and AP convertase was formed on residual cell-bound C3b by incubating with factor B and factor D and developing lysis with NHSΔBH as described in the previous paragraph. NHSΔBH was generated as described previously.21 Fluid-phase cofactor activity was determined as described previously.18 Briefly, C3b (1.2μM), fI (23nM), and fH or fH/FHR3 (molar equivalents ranging from 0.7 to 41nM) were mixed and incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes. The reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue, and cofactor activity was determined by the extent of proteolysis of C3b α′-chain to the 68-kDa and 41-kDa fragments.

To assess binding to heparin, proteins were loaded onto a 1 mL HiTrap Heparin HP affinity column (GE Healthcare) in 10mM phosphate, 50mM NaCl, pH 7.4. The column was washed to remove unbound sample, and protein was eluted in the same buffer using a linear NaCl gradient to 600mM NaCl.

Results

Complement assays, fH autoantibody screening, and mutation screening

The serum levels of C3, fH, and fI in the affected persons and the unaffected carriers were all within the normal range (Table 1). However, the C3 levels were all at the lower end of normal in the affected persons. In one affected person (V:4), the serum level of C4 was low at 0.15 g/L. Screening for fH autoantibodies was negative in all affected persons. Mutation screening of CFH, CFI, CD46, C3, CFB, THBD, and CFHR5 showed no abnormalities.

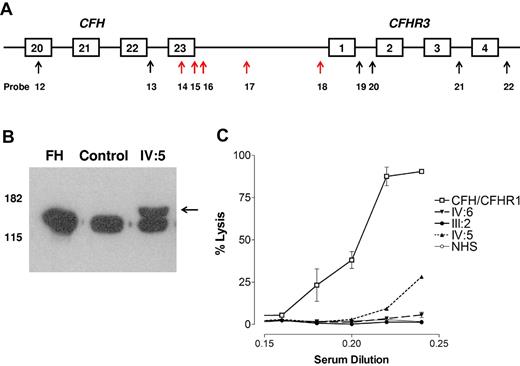

MLPA

In all the affected persons (III:6, IV:5, and V:4, as shown in Figure 1), the MLPA showed probe ratios between 0.3 and 0.7 for probes 14 to 18 (Table 2 and indicated by red arrows in Figure 4A, the data generated from the analysis in V:4 is shown in supplemental Figure 2). This suggested that there was a heterozygous deletion extending from CFH intron 22 to the 5′ untranslated region of CFHR3. Further screening of other family members showed a similar pattern in 4 unaffected persons (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6) at age 61, 54, 52, and 28 years, respectively.

MLPA, Western blotting, and hemolytic assay. (A) MLPA results. The arrows indicate the position of the MLPA probes. Red arrows showed a probe ratio of 0.3 to 0.7. (B) Western blotting. Sera from a control person and one affected person from family A (IV:5) and purified fH (Comptech) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. fH was detected as described in “Western blotting.” A higher molecular weight band (indicated by the arrow) is seen in IV:5. (C) Hemolytic assay. Serum from an affected aHUS patient known to carry a heterozygous CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene lyses the sheep red blood cells in a dose-dependent manner. Serum from an affected person (IV:5) known to carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene also lyses the cells but to a lesser extent. Sera from 2 unaffected persons (III:2 and IV:6) who carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene does not lyse the cells.

MLPA, Western blotting, and hemolytic assay. (A) MLPA results. The arrows indicate the position of the MLPA probes. Red arrows showed a probe ratio of 0.3 to 0.7. (B) Western blotting. Sera from a control person and one affected person from family A (IV:5) and purified fH (Comptech) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. fH was detected as described in “Western blotting.” A higher molecular weight band (indicated by the arrow) is seen in IV:5. (C) Hemolytic assay. Serum from an affected aHUS patient known to carry a heterozygous CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene lyses the sheep red blood cells in a dose-dependent manner. Serum from an affected person (IV:5) known to carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene also lyses the cells but to a lesser extent. Sera from 2 unaffected persons (III:2 and IV:6) who carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene does not lyse the cells.

The breakpoint and size of the deletion

A PCR product was obtained using a forward primer designed to anneal in CFH exon 22 and a reverse primer designed to anneal in CFHR3 exon 1. Sequencing the product showed the breakpoint (Figure 2B) with a change from CFH intron 22 sequence to CFHR3 5′-UTR sequence with 2 bases (AG) interposed. Immediately adjacent to the breakpoint was a 4-bp region of microhomology (shown underlined in Figure 2C). The length of the deletion was 27 983 bp.

CFH cDNA sequencing

In IV:5 (affected) cDNA sequencing confirmed the presence of message from a hybrid CFH/CFHR3 gene (Figure 3C). The sequence showed that this gene was composed of 27 coding exons, the first 22 of which were derived from CFH exons 1 to 22 and the terminal 5 from exons CFHR3 exons 2 to 6. The protein product of this gene is a 24-SCR protein (fH/CFHR3) where SCRs 1 to 19 are derived from fH SCRs 1 to 19 and SCRs 20 to 24 from fH-related protein 3 SCRs 1 to 5 (Figure 3D). The cDNA sequence shows that the first amino acid of what was previously SCR1 of CFHR3 changes from valine to leucine. This is because the first base of the codon that encodes that amino acid is derived from the last base of exon 1 of CFHR3. This in the hybrid gene is replaced by the last base of exon 22 of CFH.

Western blotting

Western blotting showed 2 distinct anti–fH reactive species in the sera of affected persons. Examination of the sera of IV:5 with SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the 35H9 anti–human fH monoclonal antibody (binds to SCR 1 of fH) showed a band characteristic of normal fH but also revealed a higher molecular weight band likely representing the fH/CFHR3 hybrid protein (Figure 4B). Use of polyclonal anti–human factor or OX23 yielded identical results.

Expression levels

The total fH concentration in IV:6 measured using OX-24 was 155 μg/L, the His402 isoform measured with MBI-7 was 110 μg/L Tyr402, and the Tyr 402 isoform measured with MBI-6 was 82 μg/L.

Hemolytic assay

Normal human serum did not lyse sheep red blood cells (Figure 4C), whereas serum from an affected aHUS patient known to carry a heterozygous CFH/CFHR1 hybrid gene lysed the cells in a dose-dependent manner. Serum from an affected person (IV:5) known to carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene also lysed the cells but to a lesser extent. Sera from 2 unaffected persons (III:2 and IV:6) who carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene did not lyse the cells.

Functional studies

To functionally characterize the hybrid fH/CFHR3 protein, plasma from an unaffected carrier (IV:6) who was heterozygous for the fH Tyr402His polymorphism was subjected to affinity chromatography on MBI-7, specific for the fH His402 variant, and MBI-6, specific for fH Tyr 402. The 2 plasma allele products were thus isolated from each other from both the fH/CFHR3 carrier and a normal control person who was also heterozygous for the 402 polymorphism (Figure 5). This shows that the Tyr 402 isoform from IV:6 represents the fH/CFHR3 hybrid protein. Proteins were passed over a size exclusion column to remove aggregates and to exchange buffer and function was analyzed.

Purification of fH and fH/CFHR3. Monoclonal antibodies specific for fH-402Tyr or fH-402His were coupled to HiTrap affinity columns and used to separate the allelic fH variants from a heterozygote control or the carrier IV:6 (the latter carried the mutated protein on the CFH402Y allele). The purified protein was eluted from the column, concentrated, and subjected to size exclusion on a Supedex 200 column (supplemental Figure 2). The purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (A) and by Western blot with allele-specific monoclonal antibodies (B). This Western blot confirms that the mutant protein is encoded on the fH-402Tyr allele and illustrates that there is no cross-contamination of the protein preparations.

Purification of fH and fH/CFHR3. Monoclonal antibodies specific for fH-402Tyr or fH-402His were coupled to HiTrap affinity columns and used to separate the allelic fH variants from a heterozygote control or the carrier IV:6 (the latter carried the mutated protein on the CFH402Y allele). The purified protein was eluted from the column, concentrated, and subjected to size exclusion on a Supedex 200 column (supplemental Figure 2). The purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (A) and by Western blot with allele-specific monoclonal antibodies (B). This Western blot confirms that the mutant protein is encoded on the fH-402Tyr allele and illustrates that there is no cross-contamination of the protein preparations.

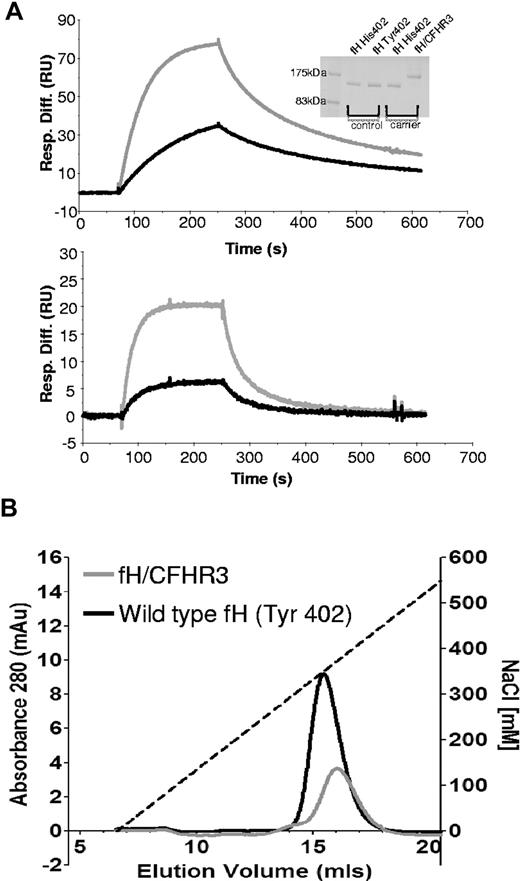

The ability of wild-type fH and fH/CFHR3 to interact with its ligands, C3b and heparin, was assessed by surface plasmon resonance and affinity chromatography, respectively. C3b was coupled to a Biacore chip using thioester coupling, and purified fH or fH/CFHR3 was flowed across (Figure 6A). Both wild-type and hybrid proteins bound tightly to the surface at various concentrations. “Tailing” of the trace is the result of crosslinking of C3b molecules on the surface by multiple C3b-binding domains in fH, increasing binding avidity. This is particularly marked with fH/CFHR3, suggesting that the CFHR3 domain within the hybrid was also able to interact with C3b. Salt elution from a heparin column demonstrated that wild-type fH (Tyr 402) eluted at 350mM NaCl, whereas fH/CFHR3 eluted at 371mM NaCl, indicating that the hybrid bound with higher affinity to heparin (Figure 6B).

Ligand binding activities of fH and fH/CFHR3. (A) C3b was thiol-coupled to the surface of a CM5 Biacore chip at a high density (1200 RU). Thiol-coupling results in clustering of C3b on a surface, promoting cross-linking and avidity effects resulting from multisite binding. When fH (bottom) or fH/CFHR3 (top) flowed across this surface at 500 ng/mL (gray line) or 125 ng/mL (black line), enhanced binding of fH/CFHR3 was evident. This cannot be accounted for by increased mass (155 kDa vs 186 kDa); it is probably the result of binding through the CFHR3 domain in addition to the fH SCRs. The “tailing” effect illustrates avidity effects in both traces; kinetics cannot be accurately measured under these conditions. Inset: Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of fH and fH/CFHR3 purified on allele-specific affinity columns. (B) Purified proteins (402Y) were bound to a HiTrap heparin column and eluted with NaCl. The fH/CFHR3 mutant (gray) eluted at 371mM and fH (black) at 350mM, indicating enhanced binding through the C-terminus to heparin. Dashed line indicates salt gradient.

Ligand binding activities of fH and fH/CFHR3. (A) C3b was thiol-coupled to the surface of a CM5 Biacore chip at a high density (1200 RU). Thiol-coupling results in clustering of C3b on a surface, promoting cross-linking and avidity effects resulting from multisite binding. When fH (bottom) or fH/CFHR3 (top) flowed across this surface at 500 ng/mL (gray line) or 125 ng/mL (black line), enhanced binding of fH/CFHR3 was evident. This cannot be accounted for by increased mass (155 kDa vs 186 kDa); it is probably the result of binding through the CFHR3 domain in addition to the fH SCRs. The “tailing” effect illustrates avidity effects in both traces; kinetics cannot be accurately measured under these conditions. Inset: Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of fH and fH/CFHR3 purified on allele-specific affinity columns. (B) Purified proteins (402Y) were bound to a HiTrap heparin column and eluted with NaCl. The fH/CFHR3 mutant (gray) eluted at 371mM and fH (black) at 350mM, indicating enhanced binding through the C-terminus to heparin. Dashed line indicates salt gradient.

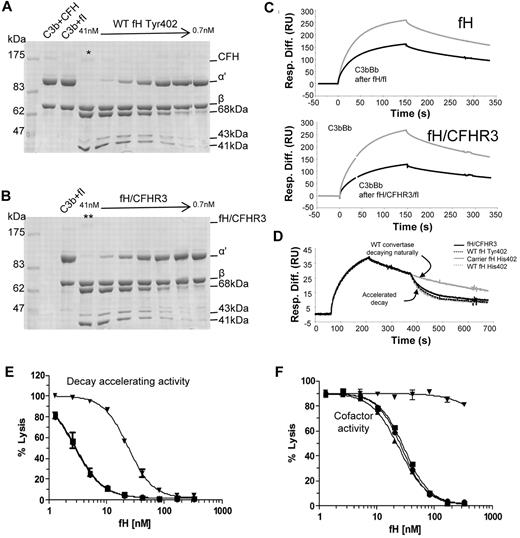

To investigate whether the N-terminal activities of the hybrid protein were functional in the fluid phase, a cofactor activity assay was carried out. Identical increasing molar equivalents of fH or fH/CFHR3 were added to purified C3b in the presence of fI and incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes. Data in Figure 7A and B and supplemental Figure 3 indicate that fH and fH/CFHR3 have equivalent cofactor activity for fI-mediated inactivation of fluid-phase C3b. Cofactor activity was also interrogated using surface plasmon resonance (Figure 7C); purified fH or fH/CFHR3 was flowed across the C3b surface in the presence of fI and ability of C3b on the chip to form a convertase before and after fH/fI treatment was assessed. In accordance with data in Figure 7A, both wild-type and hybrid proteins bound C3b and acted as cofactor for inactivation. The fH/CFHR3 protein had better activity, probably because of the enhanced surface binding indicated in Figure 6B; crosslinking of C3b molecules (leading to increased binding) occurred only on the chip surface and not in the fluid-phase assay. Decay accelerating activity for the AP C3 convertase, C3bBb, was also investigated on the chip surface. C3b was coupled to the chip and convertase formed by flowing factors B and D. After a short period of natural decay, fH or fH/CFHR3 was injected and decay of Bb was monitored in real time (Figure 7D). Both wild-type and fH/CFHR3 proteins were able to bind C3b within the convertase and mediate decay of Bb. These data indicate that the amino-terminal regulatory domain is fully functional in the hybrid protein.

Functional activity of fH and fH/CFHR3 using isolated C3b and C3b bound to the surface of sheep erythrocytes. (A-B) Cofactor activity was tested in the fluid phase by incubating C3b, fI with differing concentrations (1:2 serial dilution) of either fH or (fH/CFHR3 (Tyr402 variants, position on gel indicated by */**). Functional activity of fH is indicated by loss of the C3b α′ chain and cleavage to the 68-kDa and 41-kDa bands. Both fH and fH/CFHR3 have similar cofactor activity in the fluid phase indicating that the amino terminal domains are fully functional. (C) Cofactor activity was confirmed by immobilizing C3b on a biacore chip (1200 RU) and flowing fH (7nM, top) or fH/CFHR3 (6nM, bottom) over the surface with fI (5 μg/mL). The surface was regenerated, and the ability to form convertase was measured after (black line) treatment with cofactor and fI and compared with activity before (gray line) treatment (fH, top; fH/CFHR3, bottom). Both fH and fH/CFHR3 had cofactor activity as evidenced by decrease in ability of C3b to form convertase. (D) Decay accelerating ability for the AP convertase was tested by forming C3bBb on a Biacore chip surface (370 RU amine-coupled C3b). After 160 seconds of natural decay, fH (34nM, Tyr variant from control, gray line) or fH/CFHR3 mutant protein (34nM, black line) flowed across the surface (120 seconds). Both efficiently decayed the convertase as did the fH His402 variants from carrier or control (dashed lines). Background binding of fH or fH/CFHR3 to the C3b surface alone was subtracted, and these data are shown. (E) Decay accelerating activity of purified fH and the hybrid protein was tested in hemolysis assays. C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes bearing the AP C3 convertase were incubated with fH proteins for a set length of time. The extent of lysis developed using NHSΔBH reflected the residual convertase remaining after incubation with fH proteins. Proteins from both a control person and a carrier of the fH/CFHR3 hybrid protein were tested (▾ represents fH/CFHR3 carrierTyr402; ▴, carrier His402; ■, control Tyr402; and ●, control His402). (F) Cell surface cofactor activity of purified fH proteins was assessed by incubating with C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes and fI for a defined length of time. Cells were washed and AP convertase formed on the residual C3b by incubation with factor B and factor D. Lysis was developed using NHSΔBH and reflected the residual C3b remaining after incubation with fH proteins; symbols as in panel E.

Functional activity of fH and fH/CFHR3 using isolated C3b and C3b bound to the surface of sheep erythrocytes. (A-B) Cofactor activity was tested in the fluid phase by incubating C3b, fI with differing concentrations (1:2 serial dilution) of either fH or (fH/CFHR3 (Tyr402 variants, position on gel indicated by */**). Functional activity of fH is indicated by loss of the C3b α′ chain and cleavage to the 68-kDa and 41-kDa bands. Both fH and fH/CFHR3 have similar cofactor activity in the fluid phase indicating that the amino terminal domains are fully functional. (C) Cofactor activity was confirmed by immobilizing C3b on a biacore chip (1200 RU) and flowing fH (7nM, top) or fH/CFHR3 (6nM, bottom) over the surface with fI (5 μg/mL). The surface was regenerated, and the ability to form convertase was measured after (black line) treatment with cofactor and fI and compared with activity before (gray line) treatment (fH, top; fH/CFHR3, bottom). Both fH and fH/CFHR3 had cofactor activity as evidenced by decrease in ability of C3b to form convertase. (D) Decay accelerating ability for the AP convertase was tested by forming C3bBb on a Biacore chip surface (370 RU amine-coupled C3b). After 160 seconds of natural decay, fH (34nM, Tyr variant from control, gray line) or fH/CFHR3 mutant protein (34nM, black line) flowed across the surface (120 seconds). Both efficiently decayed the convertase as did the fH His402 variants from carrier or control (dashed lines). Background binding of fH or fH/CFHR3 to the C3b surface alone was subtracted, and these data are shown. (E) Decay accelerating activity of purified fH and the hybrid protein was tested in hemolysis assays. C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes bearing the AP C3 convertase were incubated with fH proteins for a set length of time. The extent of lysis developed using NHSΔBH reflected the residual convertase remaining after incubation with fH proteins. Proteins from both a control person and a carrier of the fH/CFHR3 hybrid protein were tested (▾ represents fH/CFHR3 carrierTyr402; ▴, carrier His402; ■, control Tyr402; and ●, control His402). (F) Cell surface cofactor activity of purified fH proteins was assessed by incubating with C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes and fI for a defined length of time. Cells were washed and AP convertase formed on the residual C3b by incubation with factor B and factor D. Lysis was developed using NHSΔBH and reflected the residual C3b remaining after incubation with fH proteins; symbols as in panel E.

To measure the ability fH and fH/CFHR3 to control complement deposited on cell surfaces coated in sialic acid, sheep E were coated in C3b or C3bBb and decay and cofactor activity determined. To measure AP convertase decay-accelerating activity, sheep erythrocytes bearing the AP convertase were incubated with fH or fH/CFHR3 for a specified time. Residual AP convertase was determined by measuring cell lysis after reconstitution of remaining complement components. Decay accelerating activity of fH/CFHR3 was dramatically reduced compared with the fH His402 variant isolated from the carrier IV:6 (IH50 His402 3nM vs fH/CFHR3 24nM; Figure 7E), representing an 8-fold decrease in activity. The activity of fH His402 was identical to that of both fH variants isolated from the control person. Cofactor activity for cell surface-associated convertase was determined by incubating C3b-coated sheep erythrocytes with fI in the presence of increasing molar equivalents of purified fH or hybrid protein. Residual, functional surface-bound C3b was determined by cell lysis after formation of the AP convertases and lytic pathway reconstitution. Calculated IH50 for His402 was 25nM, whereas no cofactor activity was observed for fH/CFHR3 in the concentration range used (Figure 7F); activity of the fH His402 variant was comparable to proteins isolated from the healthy control. Thus, cofactor activity of the mutant protein was not measurable at concentrations more than 10-fold the IH50 of wild-type proteins. These data show that in the presence of surface that bears glycosaminoglycans, functional activity of fH/CFHR3 is severely impaired.

Genotyping and CFHR1/CFHR3 copy number

The genotyping results for CD46 and CFH susceptibility factors are shown in Table 3. Of the affected persons (III:6, IV:5, and V:4), 2 were heterozygous for the at-risk G allele of CD46 −652A > G (rs2796267) and one was homozygous; 2 were heterozygous for the at-risk G allele of CD46 −366A > G (rs2796268) and 2 were heterozygous for the at-risk C allele of CD46 c.4070 T > C (rs7144). From these results, we inferred that 2 of the 3 affected persons in the family (III:6 and V:4) were heterozygous for the at-risk CD46 haplotype, CD46GGAAC. Of the unaffected persons who carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6), 3 were heterozygous for the at-risk G allele of CD46 −652A > G (rs2796267), one was heterozygous for the at-risk G allele of CD46 −366A > G (rs2796268), and one was heterozygous for the at-risk C allele of CD46 c.4070 T > C (rs7144). From these results, we inferred that one (III:7) of the 4 unaffected persons carrying the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene in the family was heterozygous for the at-risk CD46 haplotype, CD46GGAAC. Of the affected persons (III:6, IV:5, and V:4), 2 were heterozygous for the at-risk T allele of CFH −331C > T (rs3753394) and one was homozygous; one was heterozygous and 2 were homozygous for the at-risk G allele of CFH c.184G > A; one was heterozygous for the at-risk T allele of CFH c.1204C > T; p.His402Tyr (rs1061170) and 2 were homozygous; 2 were heterozygous for the at-risk G allele of CFH c.2016A > G; p.Gln672Gln (rs3753396) and one was homozygous; 2 were heterozygous for the at-risk T allele of CFH c.2808G > T;p.Glu936Asp (rs1065489) and one was homozygous. From these results, we inferred that one of the affected persons (IV:5) was homozygous for the CFH haplotype, CFHTGTGGT (also known as the CFH-H3), which is associated with an increased risk of aHUS22 and the other 2 (III:6 and V:4) were heterozygous. Of the unaffected persons who carry the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6), all were heterozygous for the at-risk T allele of CFH −331C > T (rs3753394); one was heterozygous and 3 were homozygous for the at-risk G allele of CFH c.184G > A; 3 were heterozygous for the at-risk T allele of CFH c.1204C > T; p.His402Tyr (rs1061170) and one was homozygous; all 4 were heterozygous for the at-risk G allele of CFH c.2016A > G; p.Gln672Gln (rs3753396); all 4 were heterozygous for the at-risk T allele of CFH c.2808G > T;p.Glu936Asp (rs1065489). From these results, we inferred that all of the 4 unaffected persons carrying the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene in the family were heterozygous for CFHTGTGGT.

CD46/CFH susceptibility factors and CFHR1/CFHR3 copy number in the affected persons (III:6, IV:5, and V:4) and the unaffected carriers (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6) of the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene

| Patient ID . | CD46 −652A > G (rs2796267) . | CD46 −366A > G (rs2796268) . | CD46 c.4070T > C (rs7144) . | CFH −331C > T (rs3753394) . | CFH c.184G > A Val62Ile . | CFH c.1204C > T His402Tyr (rs1061170) . | CFH c.2016A > G Gln672Gln (rs3753396) . | CFH c.2808G > T Glu936Asp (rs1065489) . | CFHR1 copy no. . | CFHR3 copy no. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III:2 | AG | AA | TT | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| III:6 | AG | AG | TC | CT | GA | TT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| III:7 | AG | AG | TC | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| III:9 | AA | AA | TT | CT | GA | TT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| IV:5 | AG | AA | TT | TT | GG | TT | GG | TT | 2 | 2 |

| IV:6 | AG | AA | TT | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| V:4 | GG | AG | TC | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| Patient ID . | CD46 −652A > G (rs2796267) . | CD46 −366A > G (rs2796268) . | CD46 c.4070T > C (rs7144) . | CFH −331C > T (rs3753394) . | CFH c.184G > A Val62Ile . | CFH c.1204C > T His402Tyr (rs1061170) . | CFH c.2016A > G Gln672Gln (rs3753396) . | CFH c.2808G > T Glu936Asp (rs1065489) . | CFHR1 copy no. . | CFHR3 copy no. . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III:2 | AG | AA | TT | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| III:6 | AG | AG | TC | CT | GA | TT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| III:7 | AG | AG | TC | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| III:9 | AA | AA | TT | CT | GA | TT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| IV:5 | AG | AA | TT | TT | GG | TT | GG | TT | 2 | 2 |

| IV:6 | AG | AA | TT | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

| V:4 | GG | AG | TC | CT | GG | CT | AG | GT | 2 | 2 |

All the affected persons and unaffected carriers had 2 copies of CFHR1 and CFHR3. However, one copy of CFHR3 is incorporated into the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene.

Discussion

In this study, we have found in a family where 3 persons have been affected by aHUS that a deletion extending from CFH intron 22 to the 5′ region of CFHR3 has resulted in the formation of a novel CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene. Furthermore, we have shown that this deletion has arisen in an NAHR-independent manner. The finding of microhomologous sequences flanking the deletion breakpoints suggests that the underlying mechanism is MMEJ, a process characterized by erroneous repair of DNA double-strand breaks.12 This has been described previously for other human Mendelian diseases, including cystic fibrosis23 and Krabbe disease.24 That it should be seen in aHUS is not unexpected in view of the macrohomology and microhomology found in the segment of chromosome 1 containing the genes for fH and the 5 fH-related proteins. We use the term macrohomology to describe the duplicated segments (also known as low copy repeats that are characteristic of this region of chromosome 1). By microhomology, we are referring to the 4- to 25-bp homologous sequences that are used to repair double-strand DNA breaks. Wherever there are duplicated segments, it is probable that within the segments there will be such small homologous sequences.

We have shown that the protein product of this gene, a 24-SCR protein, is secreted, albeit at slightly lower levels than wild-type fH. We have found that decay accelerating and cofactor activities of this protein were maintained in the fluid phase but were significantly impaired in cell-based assays. We have shown that this is secondary to a profound impairment of the function of the recognition domain whereby SCR 20 of fH has been replaced by SCRs 1 to 5 of CFHR3. Impaired function on the cell surface implies that fH cannot orient correctly on C3b to mediate decay and cofactor activity. Binding of SCRs 1 and 4 to known sites on C3b is crucial for both activities.25–27 The remainder of the fH loops back enabling SCR 19 to bind to the C3dg domain (supplemental Figure 4A),28,29 SCR 7/SCR 20 to anchor fH to the surface, and SCR20 to bind to an additional C3d.30 That fH/CFHR3 bound better to heparin than did native fH implies that binding through SCRs 7 and 21 (equivalent to SCR2 of CFHR3) overcame the loss of binding mediated by fH SCR20.31,32 Despite this, the loss of function suggests that SCRs 1 to 4 of fH/CFHR3 do not bind correctly on the surface of C3b. It is possible that SCRs 23 and 24 of fH/CFHR3 (equivalent to SCRs 4 and 5 of CFHR3) compete with, or dislocate, SCR4 from its critical binding site on C3b (supplemental Figure 4B), either directly or because of the extra length of the molecule stretching away from C3b. The glycosaminoglycan-binding site in the CFHR3 domain may additionally interfere with correct orientation of SCRs 1 to 4 on C3b by fixing the conformation of fH/CFHR3 on the surface. Hence, the carboxy-terminal domains of fH/CFHR3 may act as an “internal competitive inhibitor ” preventing correct function of the amino-terminal domains within the mutant protein. In the presence of wild-type fH, fH/CFHR3 may also exert a dominant negative effect, preventing the normal protein from locating to the surface by competing directly with its amino-terminal C3b-binding domains. The results of this study, therefore, provide a unique insight into the mechanisms by which fH regulates complement at the cell surface.

This family, like others affected by aHUS, shows evidence of nonpenetrance. Two obligate carriers (II:2 and II:7) died at age 82 and 81 years, respectively, without any history of renal disease. Of the other members of the family who have been screened, we have identified 4 unaffected carriers (III:2, III:7, III:9, and IV:6), age 61, 54, 52, and 28 years, respectively. The 3 affected persons in this family (III:6, IV:5, and V:4) first manifested aHUS at the ages of 44, 25, and less than 1 year. In familial aHUS associated with a CFH mutation, a penetrance of 59% has previously been reported.33 This was based on an analysis of a number of small families with different mutations. In our family, 3 of 9 persons carrying the CFH/CFHR3 hybrid gene (including obligate carriers) have developed aHUS, giving a penetrance of 33%. Because we have not yet screened all the members of the family, this value may be lower. Moreover, such a cross-sectional analysis does not take into account age-related penetrance, and unaffected carriers in this family may still be at risk of developing the disease. It has been shown that additional susceptibility factors in CD46 and CFH are associated with an increased predisposition to aHUS in those known to have a mutation in a complement gene.22,34 In particular, there are 2 at-risk haplotypes, CD46GGAAC and CFHTGTGGT, which predispose to development of aHUS. In this family, we inferred that 2 of 3 affected persons compared with 1 of 4 unaffected carriers were heterozygous for CD46GGAAC and that one affected person was homozygous for CFHTGTGGT and the other 2 were heterozygous compared with 4 of 4 heterozygous unaffected carriers. Besides such at-risk haplotypes, it is also recognized that additional mutations in another complement gene or antibodies against a complement protein can increase the risk of developing the disease.35 We did not find a mutation in any of the other genes known to be associated with aHUS, but it is interesting that all the affected persons had a C3 level lower than the unaffected carriers. It is possible that they carry an additional mutation in another complement gene that has not yet been shown to be associated with the disease. Likewise, we did not detect an fH autoantibody in any of the affected persons, but it is possible that they possess other, as of yet, unreported antibodies against complement proteins. Besides rare and common genetic variants, a trigger is frequently reported in many aHUS patients. In this family, pregnancy in IV:5 was the most obvious trigger.

The presence of low copy repeats in this region of chromosome 1 is well recognized to predispose to the development of genomic disorders through both gene conversion events7 and NAHR.36 The latter has been shown to result in the deletion of genes encoding the fH-related proteins (CFHR1, CFHR3, and CFHR4)8,10 and the formation of hybrid genes (CFH/CFHR1).6 These genomic disorders could be considered as being forms of “macrohomology.” Low copy repeats associated with NAHR consist usually of DNA blocks of between 10 and 400 kb.37 We here describe, for the first time, a genomic disorder affecting CFH and the CFHRs that has arisen through MMEJ. In this family mutation, screening of CFH with direct fluorescent sequencing showed no abnormality and, if MLPA had not been undertaken the molecular mechanism predisposing to aHUS, would have gone unrecognized.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Judith Goodship for critically reviewing the manuscript and Dr Svetlana Hakobyan for advice with fH variant-specific ELISAs.

This work was supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (G0701325 and G0701298) and the Northern Counties Kidney Research Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: T.H.J.G. and C.L.H. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and N.J.F., B.M., A.A., M.W., D.R., D.S., D.K., L.S., K.J.M., and C.L.H. performed the research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.H.J.G is a scientific advisor for Alexion Pharmaceuticals and has received grant support from the same company. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Timothy H. J. Goodship, Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Central Parkway, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 3BZ, United Kingdom; e-mail: t.h.j.goodship@ncl.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

C.L.H. and T.H.J.G. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal