Since the first publication describing a potential role of TNF and IL10 polymorphisms in predicting GVHD,2 a large number of reports have described a wide range of SNPs that are often also associated with inflammatory disease or autoimmune disease. Among the most studied but also with variable results have been IL10, TNF, and NOD2.

Of the 40 published candidates in the study by Chien et al, only 16 had usable data (genotype or imputed) for analysis. Interestingly, of all the SNPs analyzed, IL6 was the most consistent. The IL6174 G genotype has also often been consistently associated with increased GVHD and increased serum levels of IL-6 that have also correlated with C reactive protein levels. Of the other SNPs that could be assessed by genotyping or imputation were those of CTLA4, MTHFR (5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase), and IL2, all of which were over the P < .05 threshold. In total, 6 SNPs could be genotyped and 10 could be imputed with therefore only 16 of 40, or 40%, available for analysis. The results from the imputed IL10 SNPs (rs 1800871 and rs 1800872) replicated previous studies and this method of analysis could well be useful in future studies. However, imputed data are not without drawbacks and are limited by the quality of the original SNP data.

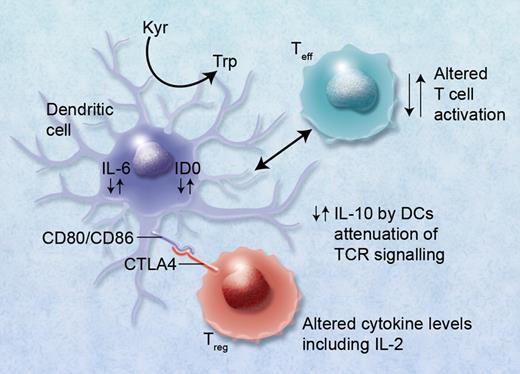

Although many of the genes associated with HSCT outcome have also been implicated in autoimmune disease, few have retained significance after GWAS. CTLA4 is the exception; it has been implicated in autoimmune thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and type1 diabetes.3 In previous studies in the HLA identical sibling HSCT setting, the presence of the donor CT60 polymorphism (G allele; rs 3087243) in the CTLA4 gene reduced overall survival (increased relapse) and increased the development of GVHD in the presence of the AA genotype.4 The opposite of these results was observed by Chien et al.1 Further studies in a matched unrelated donor cohort by Vannucchi et al could not confirm all of these findings, although the donor AA genotype predicted both grade III-IV acute and extensive chronic GVHD.5 The T-cell cytotoxic CTLA-4 antigen is involved in T-cell activation and HLA binding via the antigen-independent signaling molecules involving the B7 (CD80/CD86)/CD28 interleukin pathway. CTLA-4 antigen is homologous to the CD28 molecules and competes for B7 binding, which results in overall down-regulation of the T-cell response and may be involved in failure of T-cell tolerance.6 This mechanism of action of CTLA-4 is important in the development of autoimmune disease, presenting a potential new target for therapeutic intervention, but is also relevant to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. CTLA is expressed on Tregs and induces indoleamine2, 3 dioxygenase (IDO), which suppresses IL-6 production in dendritic cells while IL-10 production is increased. Other cytokines such as IFNγ are potent inducers of IDO, which has recently been shown to have an important role in clinical GVHD.7 High levels of IL-6 can also make effector T cells refractory to T regulatory immunosuppression.8 The GWAS results of Chien et al identifying a limited but important number of key immunoregulatory SNPs may therefore not necessarily be a “random” event, as they may be linked and play a role in Treg immunobiology (see figure), the development of GVHD, and possible reduction in graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects involving alterations in IL-2 production as well as metabolism of methotrexate via MTHFR.

Alterations in cytokine levels including IL-10, IL-6, and IL-2 via immunoregulatory single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can lead to altered immunoregulatory function of regulatory T (Treg) and effector T (Teff) cells. Binding of CTLA4 with its receptor (possibly also via functional SNPs) with CD80/CD86, B7, proteins on dendritic cells can lead to induction of indolamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO) and the catabolism of tryptophan into proapoptotic metabolites causing immunosuppression of Teffs. Altered binding of CTLA4 conversely may lead to reduced immunosuppression via Tregs and GVHD. High IL-6 levels induced in DCs by Treg interaction can also cause alteration of Tregs to Th17 cells and may lead to or exacerbate GVHD. Professional illustration by Alice Y. Chen.

Alterations in cytokine levels including IL-10, IL-6, and IL-2 via immunoregulatory single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can lead to altered immunoregulatory function of regulatory T (Treg) and effector T (Teff) cells. Binding of CTLA4 with its receptor (possibly also via functional SNPs) with CD80/CD86, B7, proteins on dendritic cells can lead to induction of indolamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO) and the catabolism of tryptophan into proapoptotic metabolites causing immunosuppression of Teffs. Altered binding of CTLA4 conversely may lead to reduced immunosuppression via Tregs and GVHD. High IL-6 levels induced in DCs by Treg interaction can also cause alteration of Tregs to Th17 cells and may lead to or exacerbate GVHD. Professional illustration by Alice Y. Chen.

Despite more than 10 years of research using the candidate gene approach to identifying polymorphisms associated with HSCT outcome, there have been relatively few genes that consistently predict either GVHD, transplant-related mortality (TRM), or survival. This is due to a number of factors that are beyond the individual researcher's control. One is the size and heterogeneity of the transplant cohort, including age at transplant, type of conditioning, type of GVHD prophylaxis, and type of donor. Transplant protocols have also changed dramatically over the past 10 years with the instigation of reduced intensity conditioning, increased use of peripheral blood stem cells, and increasing age of the patient at time of transplant, and in reduced numbers of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients within cohorts because of successful drug trials using inatimib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the deletion in CML) and its derivatives. Validation of the results is a critical issue.

HSCT GWAS studies were initiated by Chien et al where they identified a number of SNP genotypes associated with gram negative bacteremia and bronchiolitis obliterans using a large cohort of more than 3000 patient-donor pairs for discovery and validation studies.9 A follow-up replication study further assessed 65 SNPs associated with 12 HSCT phenotyopes including those associated with acute and chronic GVHD/tolerance, acute lung or kidney injury, bronchiolitis obliterans, gram negative bacteremia, CMV activation, overall survival, transplant-related mortality, and relapse.10 Of the 9 SNPs described by Chien et al associated with gram negative bacteremia, only 1 was successfully replicated. In conclusion, the authors suggest a fuller increase in cohort size to increase the power and odds ratio to nearer 2.0.

Other studies have failed to replicate results identifying immunomodulatory SNPs (IL10, IL1 receptor antagonist [IL1RN]) and TNF receptor II (TNFRSFIB) in a large transplant cohort of CML patients.11 This was likely due to significant clinical differences between the 2 cohorts.

These types of results illustrate the questionable clinical relevance of studies reporting low odds ratios and the importance of confirmatory studies. However, low odds ratios can still identify the encoded proteins as potentially novel drugs. This has been demonstrated in type 1 diabetes where peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor γ (PPARG) and KCNJII genes (encoding for the ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit Kir 6.2) are now major drug targets.12

GWAS and SNP studies also reveal important disease pathways that identify therapeutic targets and potential biomarkers that can be used for monitoring the disease and response to therapy. It is in this latter role that SNP analysis finds its usefulness. Transplant outcomes (especially for survival) can be done using a number of risk indices13 ). GWAS and SNP studies are used to indicate directions for therapy; for example, via T regulatory cells or pathways that indicate early events that could then be used to target novel treatment in the future.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■