Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF) is the master determinant for the activation of the angiogenic program leading to the formation of new blood vessels to sustain solid tumor growth and metastasis. VEGF specific binding to VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) triggers different signaling pathways, including phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ) and Akt cascades, crucial for endothelial proliferation, permeability, and survival. By combining biologic experiments, theoretical insights, and mathematical modeling, we found that: (1) cell density influences VEGFR-2 protein level, as receptor number is 2-fold higher in long-confluent than in sparse cells; (2) cell density affects VEGFR-2 activation by reducing its affinity for VEGF in long-confluent cells; (3) despite reduced ligand-receptor affinity, high VEGF concentrations provide long-confluent cells with a larger amount of active receptors; (4) PLC-γ and Akt are not directly sensitive to cell density but simply transduce downstream the upstream difference in VEGFR-2 protein level and activation; and (5) the mathematical model correctly predicts the existence of at least one protein tyrosine phosphatase directly targeting PLC-γ and counteracting the receptor-mediated signal. Our data-based mathematical model quantitatively describes VEGF signaling in quiescent and angiogenic endothelium and is suitable to identify new molecular determinants and therapeutic targets.

Introduction

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family plays a crucial role in angiogenesis, a central process in cancer, ischemic cardiovascular diseases, retinopathies, inflammation, and wound healing. VEGF-A is a multitasking cytokine that stimulates survival, permeability, migration, and proliferation of endothelial cells (ECs).1,2

In the endothelium, VEGF binds 2 tyrosine kinase receptors, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. The affinity of VEGF for VEGFR-1 is approximately one order of magnitude higher than the affinity for VEGFR-2, but the tyrosine kinase activity of VEGFR-1 is 10-fold weaker than that of VEGFR-2.3,4 These kinetic parameters and other evidence1,5 indicate that in adult life VEGFR-2 is the direct signal transducer for physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis, whereas VEGFR-1 mainly acts as a decoy-receptor or activates other cell types.5 The pivotal role of the VEGF/VEGFR-2 axis in angiogenesis is further supported by the clinical use of molecules targeting VEGF/VEGFR-2 axis for the treatment of solid tumors and macular degeneration.2

The binding of VEGF to VEGFR-2 triggers a cascade of signaling events starting with receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation, and followed by the activation of many downstream proteins.1 The main events proximal to activated VEGFR-2 involve the activation of PI3K and Akt, leading to EC survival.1 In parallel, activated VEGFR-2 directly recruits phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ), which is in turn phosphorylated.1,6 This pathway triggers a protein kinase C-dependent activation of MAPK cascade, leading to cell proliferation,7 promotes intracellular calcium mobilization and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation, contributing to EC permeability.8 Moreover, VEGFR-2–dependent activation of focal adhesion kinase, p38-MAPK–activated protein kinase 2/3-heat shock protein 27 axis, and Rac contributes to EC migration.1

Although the core components of VEGF signaling delineate well-defined intracellular routes, the whole scenario is complicated by the fact that cascades of signals converge and branch at many points in VEGF signaling.9

Different studies have provided compelling evidence that VEGFR-2 signaling is affected by environmental conditions, in particular by cell density,10 which is known to discriminate and characterize different functional aspects of the vasculature. Indeed, it was previously reported that confluent cells show a reduction, with respect to sparse cells, in both VEGFR-2 phosphorylation and proliferative responsiveness to VEGF,11 along with an enhanced VEGF-induced survival signal.10 Nevertheless, in confluent cells as well as in vivo blood vessels, it has been reported that VEGF administration causes a rapid phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 that parallels the disassembly of cell-cell junctions, the induction of vascular permeability, and precedes sprouting angiogenesis.12,13 On the whole, a clear description of the influence exerted by different cell confluence states on VEGF-induced signal transduction is still missing.

Here we report a quantitative experimental analysis integrated by mathematical modeling of the phosphorylation of key selected components in VEGF signal transduction, namely, VEGFR-2, PLC-γ, and Akt. We performed in vitro experiments with ECs grown in long-confluent and sparse conditions to mimic the corresponding in vivo endothelial states. In particular, long-confluent EC monolayers simulate the quiescent endothelium, which is characterized by mature cell junctions, cell contact-dependent growth inhibition, survival, and control of vessel permeability.10 Conversely, sparse cells recapitulate the condition of ECs during angiogenesis, with a motile phenotype, lack of mature cell junctions, and contact inhibition.10

Our study shows that expression and activation of VEGFR-2 strongly depend on EC density and VEGF concentration. The ensuing difference in receptor activation is then transduced downstream, through PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, consistently with distinct cell fates. Moreover, the mathematical analysis shows that at least one protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) exists directly acting on PLC-γ. Phosphatase inhibition experiments confirm this prediction, indicating that our mathematical model provides a valid framework for further investigation of the VEGF signaling pathway.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant human VEGF was purchased from R&D Systems; Na3VO4 from Sigma Aldrich; Endothall from Calbiochem (Merck Chemicals); primary antibodies anti-Akt (rabbit), anti–pSer473 Akt (clone D9E, rabbit), anti–PLC-γ1 (rabbit), anti–pTyr783 PLC-γ1 (rabbit), anti–pTyr1175 VEGFR-2 (clone D5B11, rabbit), and anti–VEGFR-2 (clone 55B11, rabbit) from Cell Signaling Technology; anti-p85 (rabbit) from Upstate (Millipore); anti–pTyr1054 VEGFR-2 (clone D1W, rabbit) from Millipore; anti–VE-cadherin (clone C-19, goat), anti–VEGFR-1 (clone EWC, mouse), anti-vinculin (clone N-19, goat), and anti-vinculin (clone H-10, mouse) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; and anti-αtubulin (clone B-5-1-2, mouse) from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cells and culture conditions

HUVECs were isolated and maintained as previously described,14 and used as pools of 5 different donors to minimize cell variability.

To obtain, long-confluent cell culture, ECs were seeded at a density of 20 × 103 cells/cm2 and after 72 hours they formed a high-density monolayer with mature cell-to-cell contacts and absence of gaps between cells.15 The presence of mature cell junctions in the long-confluent cultures was verified by immunofluorescent staining, using vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) as a specific marker (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). To obtain confluent cells with immature cell junctions and sparse cells with rare cell contacts, ECs were seeded at a density of 17 × 103 cells/cm2 and 3.5 × 103 cells/cm2, respectively, and used after 24 hours.

Time-course and dose-response assays

ECs were first starved in serum-free medium for 4 hours and then properly stimulated with VEGF. For time-course experiments, ECs were stimulated at different time points (0-30 minutes) with 0.01 or 0.75nM of VEGF as indicated. For dose-response studies, ECs were put in the presence of increasing doses of VEGF (0-1.25nM) for 5 minutes. Where indicated, Na3VO4 (1mM) and Endothall (180nM) were added 1 hour before stimulation. At the end of stimulation, cells were properly processed for Western blot analysis.

Biochemical quantification of VEGFR-2 distribution

Measurement of the relative proportion of the surface and internal pools of VEGFR-2 were performed in unstimulated starved long-confluent and sparse cells according to a previously reported methodology.16 Briefly, cells were washed in PBS and then incubated with 0.15 mg/mL sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce Chemical) in PBS for 10 minutes. After quenching of the unreacted biotinylation reagent with TBA (25mM Tris, pH 8, 137mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 2.3mM CaCl2, 0.5mM MgCl2, and 1mM Na2HPO4), cells were washed with PBS and then solubilized in lysis buffer (20mM Tris, pH 7.5, 125mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40, 1 mg/mL PMSF) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell lysates were centrifuged, and a sample (10 μL) was taken from the supernatant, which represents the total cellular VEGFR-2. The remaining supernatant was incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads (Upstate Biotechnology) for 2 hours; then the beads were collected by centrifugation and the supernatant was removed. This sample represents the internal VEGFR-2 pool. The beads were then washed with lysis buffer, and proteins were extracted from the beads by heating at 95°C with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. This sample represents the surface VEGFR-2 pool. Equivalent volumes of all 3 samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

Western blot analysis

For whole-cell lysates, HUVECs were washed twice with cold PBS and proteins were extracted with a buffer containing 0.5M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% SDS, 20% glycerol, and quantified by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Chemical). Equal amounts of each sample were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane Hybond-C Extra (GE Healthcare). Membranes were then saturated with 10% BSA and incubated with specific primary antibodies and proper HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunocomplexes were then visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence system (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). To obtain quantitative data, the immunoreactive bands were acquired using a ChemiDoc XRS charge-coupled device camera and quantified by Quantity One Version 4.6.0 analysis software (Bio-Rad). When protein phosphorylation was evaluated, housekeeping protein signals were used as normalizers.

Graphical and analysis tools

The visual representation of the network topology in Figure 1 was realized with Cell Designer (http://www.celldesigner.org; freeware), a diagrammatic network editing software that exploits the Systems Biology Graphical Notation.17 Gnuplot Version 4.2 (http://www.gnuplot.info/; freeware) was used for fits and plots of the experimental data.

Results

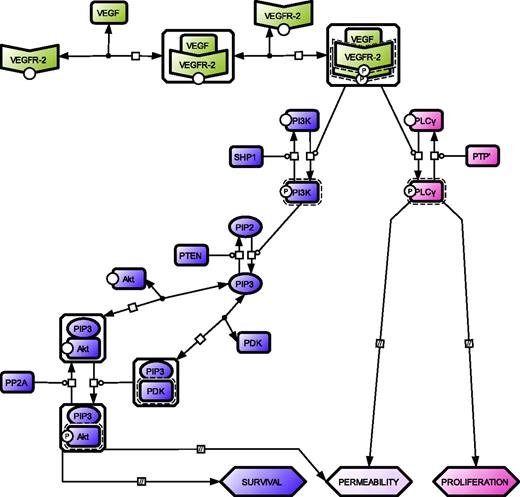

We developed a minimal model for the activation of VEGFR-2 and downstream signals (see Figure 1 for the graphical representation of the network topology). Despite its simplicity, the model reproduces some of the main features of VEGF-induced signaling, by taking into account the activation of PLC-γ and PI3K/Akt, which independently control proliferation and survival, respectively, and cooperate in promoting vessel permeability.1 The model considers the behavior of these pathways in 2 cell density conditions. Long-confluent ECs exhibit established and mature cell-to-cell contacts and recapitulate the functions of the quiescent capillary intimal layer,12 whereas sparse ECs look like angiogenic cells with proliferative and migratory capability in response to VEGF stimulus.10 Moreover, considering the angiogenic potential of VEGF, the state of long-confluent cells exposed to a high concentration of this factor is reasonably comparable to the early phase of the transition from quiescent to activated endothelium.

Network topology of the minimal model for VEGFR-2 activation and downstream signaling. Color code distinguishes the 3 modules for VEGFR-2 (green), Akt (violet), and PLC-γ (pink) activation. A VEGFR-2 monomer is engaged by a bivalent molecule of VEGF to produce the VEGF–VEGFR-2 complex, which in turn promotes the recruitment of another VEGFR-2 monomer resulting in receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation.1,18,19 The phosphorylated receptor triggers downstream signals. Akt activation moves through 3 GK modules, all characterized by a specific substrate (PI3K, PIP2, and Akt-PIP3 complex), which is interconverted from an unphosphorylated to a phosphorylated state and vice versa by a kinase and a phosphatase, respectively.20-22 PLC-γ activation consists of a single GK module where the kinase is activated VEGFR-2 and the phosphatase an unidentified PTP,23 (PTP′). For details on GK modules, see supplemental Section 1.2. For the graphical notation, see supplemental Section 1.6.

Network topology of the minimal model for VEGFR-2 activation and downstream signaling. Color code distinguishes the 3 modules for VEGFR-2 (green), Akt (violet), and PLC-γ (pink) activation. A VEGFR-2 monomer is engaged by a bivalent molecule of VEGF to produce the VEGF–VEGFR-2 complex, which in turn promotes the recruitment of another VEGFR-2 monomer resulting in receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation.1,18,19 The phosphorylated receptor triggers downstream signals. Akt activation moves through 3 GK modules, all characterized by a specific substrate (PI3K, PIP2, and Akt-PIP3 complex), which is interconverted from an unphosphorylated to a phosphorylated state and vice versa by a kinase and a phosphatase, respectively.20-22 PLC-γ activation consists of a single GK module where the kinase is activated VEGFR-2 and the phosphatase an unidentified PTP,23 (PTP′). For details on GK modules, see supplemental Section 1.2. For the graphical notation, see supplemental Section 1.6.

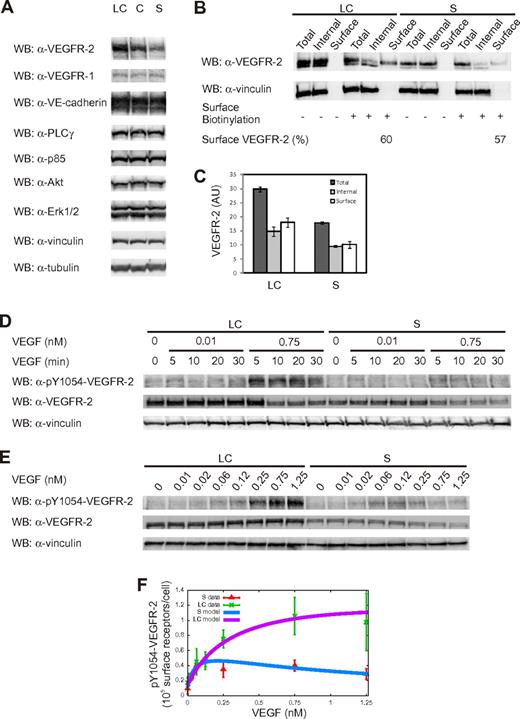

VEGFR-2 activation

To evaluate the influence of cell density on VEGFR-2 activation, we first quantified the number of receptors in whole-cell lysates obtained from unstimulated long-confluent and sparse cells. Figure 2A shows a specific increase in the protein level of VEGFR-2 as cell confluence augments. We found that the total number of VEGFR-2 molecules was of the order of 6.4 × 105/cell and 3.5 × 105/cell in the long-confluent and sparse condition, respectively (Table 1). The number of surface receptors was found to be of the order of 3.9 × 105/cell and 2.0 × 105/cell in long-confluent and sparse cells, respectively (ie, ∼ 60% of the total, regardless of the cell density; Table 1; Figure 2B-C). The observed fraction of surface receptors is consistent with previous observations16 as well as the receptor number expressed on the cell surface.24 Interestingly, a constant 2-fold ratio between VEGFR-2 numbers in long-confluent and sparse cells was observed both for the total number of receptors (1.8 ± 0.2, n = 3) and for the number of surface receptors (2.0 ± 0.2, n = 3), despite a significant variability in the absolute amount of VEGFR-2 molecules in different endothelial pools (supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that this ratio is tightly controlled by ECs.

Cell density influences VEGFR-2 expression and activation. (A) Analysis of protein expression levels under different cell density conditions. Equal amounts of whole-cell lysates (WCL) from long-confluent (LC), confluent (C), and sparse (S) ECs were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as indicated. (B) Analysis of the surface and intracellular pools of VEGFR-2 in unstimulated LC and S ECs. Surface VEGFR-2 was labeled with the membrane-impermeant sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, as reported in “Biochemical quantification of VEGFR-2 distribution.” Biotinylated surface VEGFR-2 was collected by binding to streptavidin-agarose. Aliquots of the total cell lysate, surface fraction, and internal fraction were then separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as indicated. Only the percentages of surface receptors for both LC and S ECs are shown. (C) Quantification of the relative surface and internal pools of VEGFR-2. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Time-course and dose-response analysis for VEGFR-2 phosphorylation. Starved LC and S ECs were left untreated or treated with 2 concentrations of VEGF (0.01 and 0.75nM) at the indicated time points (D) or with increasing VEGF doses (0-1.25nM) for 5 minutes (E). (F) VEGFR-2 activation as a function of VEGF concentration: comparison between experimental data (symbols) from dose-response analysis and model (solid lines, equation 6 in supplemental Section 1.1). Experimental values of phosphorylated Y1054-VEGFR-2 (pY1054-VEGFR-2) were obtained using vinculin signal as normalizer. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. The experimental values corresponding to pY1054-VEGFR-2 are displayed as the number of surface receptors per cell.

Cell density influences VEGFR-2 expression and activation. (A) Analysis of protein expression levels under different cell density conditions. Equal amounts of whole-cell lysates (WCL) from long-confluent (LC), confluent (C), and sparse (S) ECs were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as indicated. (B) Analysis of the surface and intracellular pools of VEGFR-2 in unstimulated LC and S ECs. Surface VEGFR-2 was labeled with the membrane-impermeant sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, as reported in “Biochemical quantification of VEGFR-2 distribution.” Biotinylated surface VEGFR-2 was collected by binding to streptavidin-agarose. Aliquots of the total cell lysate, surface fraction, and internal fraction were then separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted as indicated. Only the percentages of surface receptors for both LC and S ECs are shown. (C) Quantification of the relative surface and internal pools of VEGFR-2. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (D-E) Time-course and dose-response analysis for VEGFR-2 phosphorylation. Starved LC and S ECs were left untreated or treated with 2 concentrations of VEGF (0.01 and 0.75nM) at the indicated time points (D) or with increasing VEGF doses (0-1.25nM) for 5 minutes (E). (F) VEGFR-2 activation as a function of VEGF concentration: comparison between experimental data (symbols) from dose-response analysis and model (solid lines, equation 6 in supplemental Section 1.1). Experimental values of phosphorylated Y1054-VEGFR-2 (pY1054-VEGFR-2) were obtained using vinculin signal as normalizer. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. The experimental values corresponding to pY1054-VEGFR-2 are displayed as the number of surface receptors per cell.

Total and surface receptor number

| Cell population . | Total VEGFR-2 (105 molecules/cell) . | Surface VEGFR-2 (105 molecules/cell) . |

|---|---|---|

| Long-confluent | 6.4 | 3.9 |

| Sparse | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Cell population . | Total VEGFR-2 (105 molecules/cell) . | Surface VEGFR-2 (105 molecules/cell) . |

|---|---|---|

| Long-confluent | 6.4 | 3.9 |

| Sparse | 3.5 | 2.0 |

The number of total VEGFR-2 molecules was calculated as shown in supplemental Figure 2. The number of surface VEGFR-2 molecules was obtained considering the percentage of surface VEGFR-2 (reported in Figure 2B).

To investigate the VEGFR-2 response under diverse cell densities and ligand concentrations, we performed a dose-response analysis of Tyr 1054 phosphorylation, the hallmark of receptor dimerization and kinase activation.25 When long-confluent or sparse cells were challenged with a low (0.01nM) or a high (0.75nM) concentration of VEGF for 0 to 30 minutes, we found that VEGFR-2 reached its maximal activation at 5 minutes of stimulation, regardless of both VEGF concentration and cell density (Figure 2D). Therefore, this time point was selected for the dose-response analysis. By varying VEGF dose from 0.01 to 1.25nM (Figure 2E-F), we observed a similar level of VEGFR-2 activation in both cell populations at low VEGF concentrations (≤ 0.12nM), whereas long-confluent cells displayed a larger amount of phosphorylated VEGFR-2 than sparse cells at higher VEGF concentrations. Phosphorylation of Tyr 1175, which allows the binding with PLC-γ and PI3K,7,26 showed a similar behavior (supplemental Figure 4). This observation was further confirmed by stimulating ex vivo wounded mouse arterial explants with VEGF. This condition allows recapitulating the sparse and long-confluent state at the front and the rear of the vessel, respectively. In this condition, ECs at the front expressed lower phosphorylated VEGFR-2 than those at the rear (supplemental Section 2.4; supplemental Figure 5).

Of note, ligand-induced reduction of VEGFR-2 was negligible for low VEGF concentration (0.01nM) in both long-confluent and sparse cells, whereas it was evident when long-confluent and sparse cells were challenged for 10 and 5 minutes, respectively, with 0.75nM VEGF (Figure 2D).

To reproduce empirical data, we modeled the activation of VEGFR-2 as a 2-step process: (1) VEGF binding to the monomeric receptor with dissociation constant K; and (2) receptor dimerization-transphosphorylation with dissociation constant K′ (supplemental Section 1.1).18,19 This yields an equation for receptor activation as a function of ligand amount, with 1 measured parameter (the number of surface receptors T) and 3 unknowns (the 2 dissociation constants K and K′ and the autocrine VEGF concentration ϵ).27,28 The 3 unknown parameters were estimated by fitting the receptor model to experimental data (Table 2). Figure 2F shows that the model with fitted parameters accurately reproduces the experimental data. Interestingly, the value of the dissociation constant K that can be directly read as the VEGF dose corresponding to the maximal receptor activation is found to be approximately 10 times larger in long-confluent than in sparse cells. The values of K′ and ϵ are instead almost insensitive to cell density (Table 2). The estimated values of ϵ are consistent with experimental ones previously reported (0.01nM as in Serini et al27 ).

The best fit parameter set for the model describing VEGFR-2 activation

| Cell population . | K, nM . | K′ (105 surface receptors/cell) . | ϵ, nM . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-confluent | 1.79 | 3.44 | 0.03 |

| Sparse | 0.22 | 2.41 | 0.01 |

| Cell population . | K, nM . | K′ (105 surface receptors/cell) . | ϵ, nM . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-confluent | 1.79 | 3.44 | 0.03 |

| Sparse | 0.22 | 2.41 | 0.01 |

The value K = 1.79nM obtained in the long-confluent case is very close to the value 2.07nM found by Li et al,29 while the value K = 0.22nM in the sparse case is comparable with the value 0.11nM measured in a cell-free system.30 This observation suggests that in the sparse ECs VEGFR-2 is fully competent to bind the ligand as in a cell-free case, whereas in the long-confluent EC condition some molecular interferences occur. Figure 2F shows that the phosphorylation response of VEGFR-2 to low VEGF concentrations is similar for both long-confluent and sparse cells because at low VEGF doses the ligand-receptor affinity K and the number of surface receptors T compensate each other (supplemental Section 1.1). Conversely, at higher VEGF doses, T prevails, leading to the divergent responses observed in the 2 cell populations (Figure 2F).

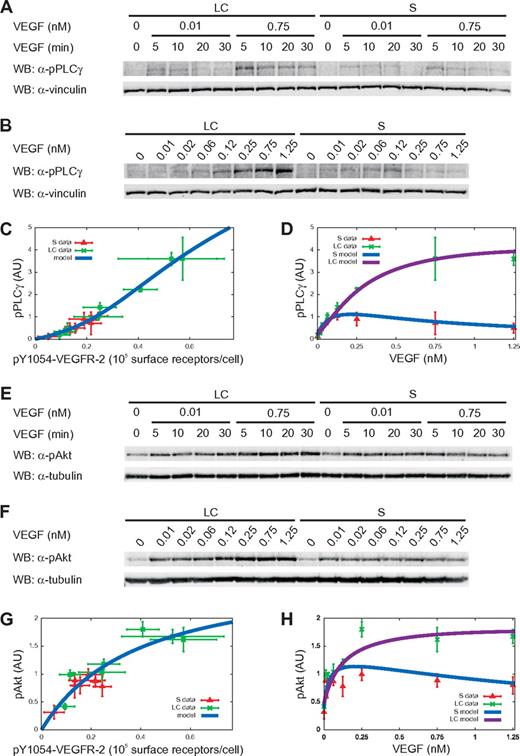

Downstream signaling

To investigate the signaling events downstream VEGFR-2 activation, we measured the phosphorylation levels of the target proteins PLC-γ and Akt both in long-confluent and sparse cells. In particular, we considered the phosphorylation levels of PLC-γ and Akt on Tyr 783 and Ser 473, respectively, because the phosphorylation of these residues is essential for their activation.20,31 Time-course experiments (Figure 3A,E) with low (0.01nM) and high (0.75nM) VEGF concentrations indicated the maximal activation of PLC-γ and Akt after 5 minutes of stimulation, which was selected for dose-dependent experiments (Figure 3B,F). As in the case of receptor activation, the activation peak was independent of ligand concentration and cell density (Figure 3A,E).

Cell density effects are propagated to downstream signal proteins. (A-B,E-F) Time-course (A,E) and dose-response analysis (B,F) for PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation was done by treating cells as described in Figure 2. (C,G) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt activation as a function of pY1054-VEGFR-2. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data (symbols) and model (equations 18 and 34 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). The receptor phosphorylation values in the x-axis are those used in Figure 2E. (D,H) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation as a function of VEGF concentration. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data and model (equations 19 and 35 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). In all graphs, experimental values of phosphorylated PLC-γ (pPLC-γ) and phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) were obtained using vinculin and tubulin signals as normalizers, respectively. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments.

Cell density effects are propagated to downstream signal proteins. (A-B,E-F) Time-course (A,E) and dose-response analysis (B,F) for PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation was done by treating cells as described in Figure 2. (C,G) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt activation as a function of pY1054-VEGFR-2. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data (symbols) and model (equations 18 and 34 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). The receptor phosphorylation values in the x-axis are those used in Figure 2E. (D,H) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation as a function of VEGF concentration. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data and model (equations 19 and 35 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). In all graphs, experimental values of phosphorylated PLC-γ (pPLC-γ) and phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) were obtained using vinculin and tubulin signals as normalizers, respectively. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments.

We considered the possibility that cell density may directly influence the downstream signaling, bypassing signaling from VEGFR-2. If this is the case, long-confluent and sparse cells would show different PLC-γ and Akt responses in correspondence to the same degree of VEGFR-2 activation. On the contrary, as shown in Figure 3C and G, the data of PLC-γ and Akt activation versus receptor phosphorylation collapse on a single curve, independently of the cell density, strongly suggesting that a single model for each protein can describe the downstream cascade in both cell populations and that PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation only depends on VEGFR-2 activation.

Figure 3D and H shows that at low VEGF concentrations (≤ 0.12nM), PLC-γ and Akt activation levels were comparable in the 2 cell populations. At larger VEGF concentrations, a higher amount of phosphorylated PLC-γ and Akt was observed in long-confluent cells because of the corresponding increase in VEGFR-2 activation. However, PLC-γ and Akt activation differed both in the steepness of the response at low VEGF doses and in the ratio of the saturation values in the 2 populations. The fact that Akt is maximally activated at relatively low VEGF doses (with respect to both the receptor and PLC-γ) highlights that the signal is amplified along its axis by a kinase chain (Figure 1), as suggested by the mathematical model proposed by Heinrich et al32 that predicts the role of kinase cascades in the positive control of signal amplitudes.

We modeled the reactions involved in PLC-γ and Akt activation as a sequence of Goldbeter-Koshland (GK) modules33 under the total quasi-steady-state approximation.34 Because PLC-γ is activated and directly recruited to VEGFR-2,1,7 a single GK module is sufficient to describe this part of the pathway (Figure 1; supplemental Section 1.3). Conversely, because Akt is activated by a chain of intermediate signaling molecules,20 we used a cascade of 3 GK modules to model this second branch of the pathway (Figure 1; supplemental Section 1.4).

Model parameters were estimated by fitting the experimental data with a single set of parameters for both long-confluent and sparse cells. As shown in Figure 3C and G, the quality of the fits is remarkable (reduced χ2 ∼ 0.01 in both cases) and the curves indicate a sigmoidal- and a Michaelis-Menten-like response for PLC-γ and Akt, respectively.

The theoretical response function obtained by combining receptor activation and downstream signals (supplemental Section 1.2) satisfactorily reproduced the experimental data (Figure 3D,H).

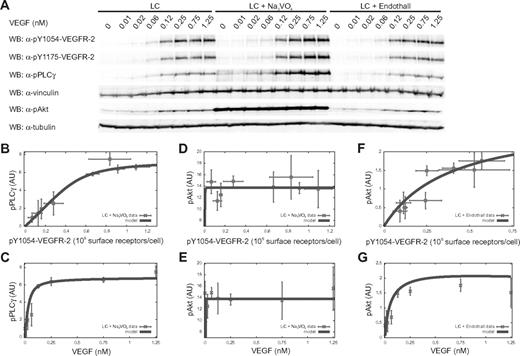

Essential role of tyrosine phosphatases

Remarkably, the response of PLC-γ to VEGFR-2 (Figure 3C) is sigmoidal-like. In general, in a sigmoidal signal-response function, 3 regimens can be characterized by low, intermediate, and high input strengths, respectively, corresponding to a small (insensitivity), high (transient), and again small (saturation) increase in response. The concentration ranged from 0 to 1.25nM VEGF allowed visualization of the sigmoidal response of PLC-γ to VEGFR-2 in the long-confluent case for the insensitivity and transient regimens (Figure 3C). Administration of VEGF concentration higher than 1.25nM did not further increase VEGFR-2 and PLC-γ phosphorylation level (supplemental Figure 6), suggesting that the saturation regimen was already reached. The sigmoidal response of PLC-γ to VEGFR-2 is compatible with the quantitative model only by assuming the contribution of at least 1 unknown PTP (PTP′ in Figure 1) directly targeting PLC-γ and counteracting the receptor-mediated phosphorylation. In long-confluent cells treated with VEGF, we investigated the effect of the generic PTP inhibitor sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4) on the phosphorylation of PLC-γ Tyr 783 and VEGFR-2 Tyr 1054 and 1175. Na3VO4 sensitized ECs to VEGF-mediated PLC-γ phosphorylation compared with untreated control cells (Figure 4A). Actually, the maximal sensitization effect occurred at 0.12nM VEGF, producing a 3-fold increase (3.1 ± 0.3, n = 3) in PLC-γ phosphorylation. On the other hand, the corresponding Na3VO4-induced effect on VEGFR-2 phosphorylation was negligible (1.1 ± 0.1- and 1.5 ± 0.3-fold increase, n = 3, on Tyr 1054 and Tyr 1175, respectively; Figure 4A). This shows both that PLC-γ is strictly controlled by specific PTPs and that receptor-targeting PTPs are not the main responsible for this regulation. SHP2, PTP1B, density-enhanced phosphatase 1 (DEP1), and vascular endothelial PTP (VEPTP) represent the main PTP candidates for indirect35-38 or direct23 PLC-γ regulation. However, single (supplemental Figure 7) and simultaneous (supplemental Figure 8) down-regulation of their expression by specific short interfering RNAs was ineffective in increasing PLC-γ activation compared with the Na3VO4-induced effect. In particular, the concurrent silencing of the aforementioned PTPs (supplemental Figure 8) produced only a slight increase in PLC-γ phosphorylation (1.4 ± 0.1-fold increase, n = 3) that correlated with the induced increase in VEGFR-2 activation (1.3 ± 0.3 and 1.4 ± 0.1-fold increase, n = 3, on Tyr 1054 and Tyr 1175, respectively). This indicates that SHP2, PTP1B, DEP1, and VEPTP act indirectly on PLC-γ and are not accountable for the strong up-regulation of PLC-γ phosphorylation observed in the presence of Na3VO4 (supplemental Figure 8). By comparing results shown in Figures 3C and 4B, it is clear that Na3VO4 treatment abolished the sigmoidal-like relationship between PLC-γ and VEGFR-2 phosphorylation. The fit of the experimental data for Na3VO4-treated cells confirms that the disappearance of the sigmoidal relation corresponds to the presence of a much lower PTP′ activity. As a consequence of PTP′ inhibition, PLC-γ reached a maximal phosphorylation level at a lower VEGF dose than in the presence of active PTP′ (compare Figure 4C with Figure 3D).

Phosphatase role in PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation. (A) Dose-response analysis for PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation. LC ECs were treated as described in Figure 3 in the presence or absence of Na3VO4 or Endothall. (B,D,F) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt activation as a function of pY1054-VEGFR-2. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data (symbols) and model (equations 18 and 34 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation, respectively, are shown for cells treated with Na3VO4 (B) and with either Na3VO4 (D) or Endothall (F). (C,E,G) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation as a function of VEGF concentration. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data and model (equations 19 and 35 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). PLC-γ is shown for cells treated with Na3VO4 (C) and Akt phosphorylation for cells treated with either Na3VO4 (E) or Endothall (G). Experimental values of pY1054-VEGFR-2 and phosphorylated PLC-γ (pPLC-γ) were obtained using vinculin signal as normalizer, whereas experimental values of phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) were obtained using tubulin signal. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments.

Phosphatase role in PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation. (A) Dose-response analysis for PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation. LC ECs were treated as described in Figure 3 in the presence or absence of Na3VO4 or Endothall. (B,D,F) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt activation as a function of pY1054-VEGFR-2. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data (symbols) and model (equations 18 and 34 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation, respectively, are shown for cells treated with Na3VO4 (B) and with either Na3VO4 (D) or Endothall (F). (C,E,G) Dose-response analysis of PLC-γ and Akt phosphorylation as a function of VEGF concentration. Symbols and solid lines represent experimental data and model (equations 19 and 35 in supplemental Sections 1.3 and 1.4). PLC-γ is shown for cells treated with Na3VO4 (C) and Akt phosphorylation for cells treated with either Na3VO4 (E) or Endothall (G). Experimental values of pY1054-VEGFR-2 and phosphorylated PLC-γ (pPLC-γ) were obtained using vinculin signal as normalizer, whereas experimental values of phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) were obtained using tubulin signal. Values are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments.

In parallel, we studied the phosphatase contribution along the VEGFR-2-Akt axis. In this case, we distinguished the effect of enzymes belonging to the PTP class, namely, SHP1 acting on PI3K and PTEN acting on PIP3,21,22 and to the protein serine phosphatase class, namely, protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) acting on active Akt20 (Figure 1).

To determine the contribution of the PTP class, we analyzed the phosphorylation of Akt Ser 473 in response to increasing concentrations of VEGF in Na3VO4-treated long-confluent cells. Compared with untreated control cells, Na3VO4 administration induced a stronger Akt phosphorylation level independently of VEGF stimulus (Figure 4A). Indeed, Akt was hyperactivated also in the basal state, consistent with previously reported data.39 This basal activation was cell density-independent and PI3K-dependent as shown by the inhibition of its enzymatic activity by LY294002, which abolished the Na3VO4-induced effect in both long-confluent and sparse cells (supplemental Figure 9). We fitted the Akt model equation to experimental data from Na3VO4-treated cells. In the treated case, Akt activation saturated already at very low VEGF concentrations (Figure 4E). The theoretical results from the comparison of treated with untreated cells suggest a lower activity of the phosphatases SHP1 and PTEN, known to regulate the activation of PI3K and the amount of PIP3, respectively (Figure 1). Then we investigated the role of PP2A by performing a set of experiments in VEGF-treated and untreated long-confluent cells in the presence of Endothall, a specific inhibitor of PP2A.40 In Endothall-treated cells, Akt phosphorylation was very close to the untreated condition (Figure 4A). Therefore, in the early time window we considered, PP2A appears to play an insignificant role in the Akt activation (compare Figure 3G-H with Figure 4F-G). Similarly, Endothall did not modify the VEGF-dependent phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 and PLC-γ (Figure 4A).

The present analysis efficiently supports the VEGFR-2 activation and signal transduction model, which is shown to correctly describe the response of the cell system to a perturbation induced by phosphatase inhibitors. The activity of a PLC-γ–specific PTP has to be assumed to explain PLC-γ response to VEGF and experimentally confirmed by its pharmacologic inhibition. Moreover, the contribution of PTPs is also relevant in the control of Akt activation independently from the presence of VEGF, as inferred by the potentiating effect of Na3VO4 on the basal phosphorylation of the enzyme.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is the formal demonstration of the influence of EC density on the activation of the early triggered signaling modules along the VEGF/VEGFR-2 axis.

To interpret the experimental data obtained in long-confluent and sparse cells, we developed a mathematical model of VEGFR-2 activation and signal transduction that quantitatively describes cell density influence on receptor phosphorylation levels and its propagation to PLC-γ and Akt.

We found that: (1) cell density influences VEGFR-2 protein level, as receptor number is 2-fold higher in long-confluent than in sparse cells; (2) cell density affects VEGFR-2 activation by reducing its affinity for VEGF in long-confluent cells; (3) despite reduced ligand-receptor affinity, high VEGF concentrations provide long-confluent cells with a larger amount of active receptors; (4) PLC-γ and Akt are not directly sensitive to cell density but simply transduce downstream the upstream difference in VEGFR-2 protein level and activation; and (5) the mathematical model correctly predicts the existence of at least one unknown phosphatase directly targeting PLC-γ and counteracting the receptor-mediated signal. The model shows that, in long-confluent cells exposed to low VEGF concentrations, a lower receptor-ligand affinity is compensated by a higher receptor number, which is also responsible for the divergent response in the 2 cell populations at higher VEGF concentrations.

Different VEGFR-2 protein levels between long-confluent and sparse cells may be a direct consequence of the presence or absence of matured cell junctions in combination with fine mechanisms of receptor trafficking and ubiquitination. Indeed, quiescent ECs have 2 surface pools of VEGFR-2: a stable pool that is complexed with VE-cadherin at the cell junctions, and a transportable pool that constantly cycles between the surface and the sorting endosome.16 Interestingly, loss of junctions would result in a loss of the stable surface pool and an overall down-regulation of VEGFR-2 from the cell.41 Moreover, it has been recently reported that tumor endothelium shows lower VEGFR-2 protein level than the healthy control tissue because of continuous ligand-induced degradation of VEGFR-2 protein.42 This suggests that VEGFR-2 protein level may actually be down-regulated in the angiogenic state versus the quiescent condition in vivo. Of note, VEGFR-2 expression may also be regulated at transcription level. In particular, it has been observed that VEGFR-2 transcript is up-regulated in blood vessels of several tumors compared with quiescent vascular networks.43,44 One may speculate that the up-regulation of VEGFR-2 mRNA in tumor vessels could ensure the cells with freshly synthesized receptors to compensate a fraction of ligand-induced VEGFR-2 degradation at sites of active angiogenesis.

Mechanisms for ligand-induced degradation of VEGFR-2 have been previously reported45 and may be responsible for the reduced amount of VEGFR-2 protein that we observed on high-dose administration of VEGF (Figure 2D). This reduction occurred more rapidly in sparse than in long-confluent cells (Figure 2D), suggesting more efficient VEGFR-2 internalization and degradation processes. This observation may account for the decrease of VEGFR-2 activity observed in sparse, but not in long-confluent, cells at high concentrations of VEGF (Figure 2E-F). Interestingly, the aforementioned reduction of VEGFR-2 phosphorylation may also result from the fact that high concentrations of ligand reduce the probability to recruit ligand unbound receptor monomers required for the dimerization/transphosphorylation process. This possibility justifies the decreased receptor activity, which is especially evident in sparse cells because they display lower number of receptors compared with the long-confluent ECs (Table 1). This additional explanation is supported by the mechanism of receptor activation according to which the binding of a bivalent VEGF molecule to a receptor monomer is followed by the recruitment of a second ligand unbound receptor monomer, leading to receptor dimerization and activation.19

The reduced ligand-receptor affinity in long-confluent cells may be caused by the presence of some molecular interferences as in the case of epidermal growth factor receptor, whose association with E-cadherin was reported to decrease ligand-receptor affinity in confluent compared with sparse cells.46 Indeed, as mentioned, VEGFR-2 is known to be able to associate with VE-cadherin.1,9,10 In particular, in quiescent blood vessels as well as in in vitro EC monolayers, VEGFR-2/VE-cadherin association was isolated as a preformed complex, transiently disrupted by high-dose administration of VEGF.13 The basal association of VE-cadherin with VEGFR-2, or the involvement of other unidentified molecular determinants peculiar of the long-confluent state, could reduce VEGF/VEGFR-2 affinity, as predicted by the model (K in Table 2).

The high level of VEGFR-2 activation observed in long-confluent cells exposed to high doses of VEGF, a condition that is no longer comparable to the quiescent state of ECs, is consistent with the well-known angiogenic potential of this factor, able to induce the transition from quiescent to angiogenic endothelium. Of note, the different levels of maximal VEGFR-2 activation in long-confluent and sparse cells are a direct consequence of the different receptor protein levels in the 2 cell populations; this variation is transduced downstream, producing diverse effects along the PLC-γ and Akt axes. The 2-fold ratio between the maximal VEGFR-2 activation in long-confluent and sparse cells is doubled along the PLC-γ axis leading to a 4-fold difference in maximal PLC-γ activation levels. Conversely, the Akt response just mirrors the difference in activated receptor levels. Interestingly, in resting ECs, the VEGF autocrine loop is mainly accountable for its prosurvival activity28 and sustained by a minimal VEGF production,27 10- to 100-fold lower than in pathologic tissues, where VEGF activates its proangiogenic program.

Mathematical analysis shows that at least one unknown PTP directly targeting PLC-γ is essential to provide the observed sigmoidal-like response to VEGF stimulation. This model prediction is supported by the data obtained from the behavior of Na3VO4-treated cells and is made more consistent by the effect observed by down-regulating the expression of SHP2, PTP1B, DEP1, and VEPTP, which are the known phosphatases described in the VEGFR-2 pathway.1 Indeed, the simultaneous silencing of these PTPs was not able to recapitulate the effect of Na3VO4 on PLC-γ activation. This result excludes the possibility that the Na3VO4-induced sensitization of PLC-γ phosphorylation could be dependent on a cooperative effect exerted by the main candidates for the regulation of PLC-γ activation. This further suggests the actual existence of at least one PTP not previously characterized as a fundamental molecular determinant of the control of VEGF-mediated PLC-γ activation. In addition, a phosphatase activity may be also implicated in the Akt regulation in unstimulated cells as suggested by the effect of Na3VO4 in increasing the basal Ser 473 phosphorylation. However, it is also possible to speculate that PTP inhibition may enhance the effect of autocrine VEGF loop already present in the basal condition.27,28

In conclusion, we provided here a systematic experimental study of EC response to VEGF stimulation in different cell density states, integrated by the development of a coherent mathematical framework that satisfactorily reproduces the observed data and predicts the relevant role of PTPs. The natural extension of our work may consist of the spatial characterization of the activation features of VEGFR-2 known to be able to associate not only with VE-cadherin, but also with integrins, neuropilin-1, and heparan sulphates1 or to signal during its endosome-mediated internalization.47 Moreover, our results prompt for future investigation aimed at identifying the unrecognized PTPs and provide a basic framework for further extensions that will shed light on the complexity of the VEGF signaling.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the F.B. laboratory for helpful discussions and M. Ushio-Fukai for reagents.

This work was supported by Italian Association for Cancer Research, Regione Piemonte (Finalized Health Research 2008, 2008bis, and 2009; Technological Platforms for Biotechnology: grant DRUIDI; Converging Technologies: grant PHOENICS; Industrial Research 2009; grant BANP), CRT Foundation (F.B.), and Foundazione Piemontese per la Ricerca sul Cancro-ONLUS (Instrumental Grant 2010-2012; 5×1000-2008). Ministry of University-Fondo per gli Investimenti della Ricerca di base (Grant Newton-RBAP11BYNP), University of Torino-Progetti di Ateneo 2011 (Grant Rethe ORTHO11RKTW). L.N. was supported by a fellowship of Italian Foundation for Cancer Research.

Authorship

Contribution: L.N. planned the study, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, supervised the analysis, supported the modeling, and wrote the paper; S.P. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; A.V. developed the mathematical model and performed the model fitting to experimental data; A.P., G.B., A.C., and A.G. contributed to the design of the mathematical framework; G.S. and L.P. performed aortic ring experiments; and F.B. revised the manuscript and supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lucia Napione, Institute for Cancer Research Treatment, Sp 142, km 3.95-10060 Candiolo, Italy; e-mail: lucia.napione@ircc.it.

References

Author notes

L.N., S.P., and A.V. contributed equally to this study.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal