Abstract

In the present study, we investigated disease characteristics and clinical outcome in young patients (< 40 years) with World Health Organization (WHO)–defined essential thrombocythemia (ET) compared with early/prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis (PMF) with presenting thrombocythemia. We recruited 213 young patients (median age, 33.6 years), ncluding 178 patients (84%) with WHO-defined ET and 35 patients (16%) showing early PMF. Median follow-up time was 7.5 years. A trend for more overall thrombotic complications, particularly arterial, was seen in early PMF compared with ET. Progression to overt myelofibrosis was 3% in ET and 9% in early PMF, but no transformation into acute leukemia was observed. Combining all adverse events (thrombosis, bleeding, and myelofibrosis), the rate was significantly different (1.29% vs 3.43% of patients/year, P = .01) in WHO-ET and early PMF, respectively. In multivariate analysis, early PMF and the JAK2V617F mutation emerged as independent factors predicting cumulative adverse events.

Introduction

Essential thrombocythemia (ET) is usually a disorder of the elderly, so most of the current information focuses on the “average” MPN patients who range in age between 55 and 65 years.1-5 Less consistent data are available in the groups of patients presenting below this median age, such as children6 and young adults, who represent approximately 20% of cases.7-10 Therefore, many clinical needs are unmet in these relatively rare subgroups. Regarding diagnosis, World Health Organization (WHO) criteria underscore the role of BM morphology in distinguishing ET from early/prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis (PMF).11-13 Early PMF presents with significantly lower hemoglobin levels and higher WBC and platelet counts, more frequent splenomegaly, and a significant higher rate for evolution into overt myelofibrosis (after ET-MF), acute leukemia (AL), and a higher incidence of mortality.14

Until now, it had not been elucidated whether in younger adults (≤ 40 years) with ET compared with early PMF, complications such as thrombosis, bleeding, or hematologic evolution are the same as in elderly patients. To address this question, in the present study, we examined a relatively large number of WHO-diagnosed ET and early PMF patients who were younger than 40 years.

Methods

A clinicopathologic database of patients who were diagnosed and treated as ET in 7 international centers was created.14 The study was approved by the institutional review board of each institution. Eligibility criteria included the availability of representative, treatment-naive BM biopsies obtained at diagnosis or within 1 year of diagnosis as the most important tool for accurate classification. A total of 213 patients (age range, 13-40 years) were retrieved from the general database of 1104 patients.14 Polycythemia Vera Study Group (PVSG) criteria15 were used for diagnoses made before 2002 and WHO criteria for diagnoses made thereafter.16,17 Hydroxyurea (60%), α-IFN (20%), and anagrelide (20%) were the drugs used in high-risk group. All BM biopsies subsequently underwent a central re-review (by J.T.) according to WHO criteria.18 As described previously,14 an overall consensus between the local pathologists and the reviewer regarding the original diagnosis of ET was reached in approximately 81% of the total cohort and in 84% of the 213 patients under study. The review process was completely blinded to outcome data. The diagnosis of overt PMF, AL transformation, and JAK2V617F determination were carried out as described previously.14,19,20

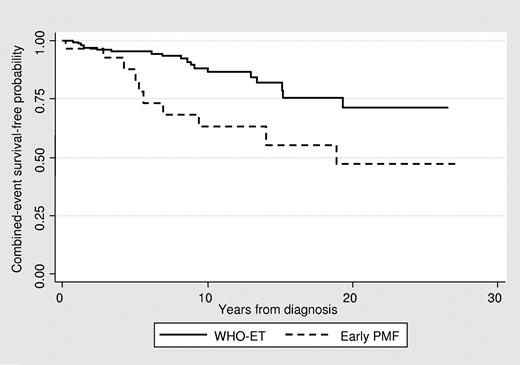

Event-free survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of event (uncensored) or last contact/date of death (censored). The Kaplan-Meier method was used for analysis of survival and the Cox proportional hazard regression model was used for multivariable analysis.

Results and discussion

Presentation

The platelet count was higher in patients with early PMF, who also showed a trend for lower hemoglobin value (P = .08), higher WBC counts (P = .10), and higher lactate dehydrogenase levels (P = .071). This pattern was consistent with the findings documented in older patients. History of/or thrombosis at presentation was found in 13% and 6% of ET and early PMF patients, respectively. Among cardiovascular risk factors, smoking was prevalent. (For details, please see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article.)

Follow-up

The median follow-up from the time of diagnosis was 7.6 years (range, 0-27) for ET and 7.4 years (range, 0-27) for early/prefibrotic PMF (Figure 1 and Table 1). During this period, no deaths or evolution of AL were registered. Transformation to clinically overt myelofibrosis was seen in 7 patients. The rate was 0.26% and 0.94% patients/year in ET and early PMF, respectively. Interestingly, in older, WHO-defined patients (supplemental Table 2) with a similar period of observation, overt fibrotic transformation was documented in 0.5% patients/year with ET and in 1% patients/year with early PMF. Therefore, the incidence of myelofibrosis appeared to be less frequent in WHO-ET young patients versus WHO-ET elderly patients. Comparison of these findings with the current literature on ET in young adults7-10 is difficult because all previous investigations in young ET patients followed the PVSG guidelines.15 The study by Alvarez-Larran et al on 126 young ET patients reported that approximately 20% of the patients showed a grade 2 reticulin fibrosis in the initial BM biopsies,8 a finding that is not consistent with WHO-defined ET, but rather with early PMF.14 Therefore, they calculated increased reticulin content in initial BM specimens as being associated with a higher risk for progression to myelofibrosis (4.7%)8 In the present study, we documented a trend for more total thrombosis (P = .086) in early PMF than in ET. The rate was 1.3% of patients/year and 0.74% of patients/year in early PMF and ET, respectively. As expected, this is clearly lower than in the older patients, in whom the rate of total thrombosis was 1.9% in early PMF and 1.7% patients/year in WHO-ET.19 In the PVSG-classified younger ET patients, the cumulative incidence of total thrombosis was estimated at 2.2% patients/year, a rate higher than that observed in our WHO-confirmed patients.

Main outcomes

| . | All patients (N = 213) . | WHO-ET (n = 178) . | Early PMF (n = 35) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up, y (range) | 7.6 (0-27) | 7.6 (0-27) | 7.4 (0-27) | .976 |

| Cytoreductive therapy, n (%) | 78 (37) | 63 (35) | 15 (43) | .459 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 137 (64) | 111 (62) | 26 (74) | .178 |

| Thrombosis during follow-up, n (%) | 16 (8) | 11 (6) | 5 (14) | .096 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.84 (0.50-1.39) | 0.74 (0.41-1.34) | 1.30 (0.49-3.47) | .326 |

| Arterial, n (%) | 11 (5) | 7 (4) | 4 (11) | .086 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.54 (0.29-1.01) | 0.46 (0.22-0.96) | 0.97 (0.31-0.31) | .284 |

| Venous, n (%) | 7 (3) | 5 (3) | 2 (6) | .323 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.38 (0.18-0.79) | 0.33 (0.14-0.79) | 0.59 (0.15-0.36) | .462 |

| Hemorrhages, n (%) | 11 (5) | 8 (5) | 3 (9) | .390 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.53 (0.28-0.98) | 0.45 (0.22-0.95) | 0.88 (0.28-2.71) | .281 |

| Evolutions in MF, n (%) | 7 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (9) | .106 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.38 (0.18-0.80) | 0.26 (0.10-0.70) | 0.94 (0.30-2.94) | .069 |

| Evolutions in AL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| All events, n (%)* | 31 (15) | 20 (11) | 11 (31) | .002 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 2.76 (2.37-3.21) | 1.29 (0.82-2.03) | 3.43 (1.85-6.37) | .010 |

| . | All patients (N = 213) . | WHO-ET (n = 178) . | Early PMF (n = 35) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up, y (range) | 7.6 (0-27) | 7.6 (0-27) | 7.4 (0-27) | .976 |

| Cytoreductive therapy, n (%) | 78 (37) | 63 (35) | 15 (43) | .459 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 137 (64) | 111 (62) | 26 (74) | .178 |

| Thrombosis during follow-up, n (%) | 16 (8) | 11 (6) | 5 (14) | .096 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.84 (0.50-1.39) | 0.74 (0.41-1.34) | 1.30 (0.49-3.47) | .326 |

| Arterial, n (%) | 11 (5) | 7 (4) | 4 (11) | .086 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.54 (0.29-1.01) | 0.46 (0.22-0.96) | 0.97 (0.31-0.31) | .284 |

| Venous, n (%) | 7 (3) | 5 (3) | 2 (6) | .323 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.38 (0.18-0.79) | 0.33 (0.14-0.79) | 0.59 (0.15-0.36) | .462 |

| Hemorrhages, n (%) | 11 (5) | 8 (5) | 3 (9) | .390 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.53 (0.28-0.98) | 0.45 (0.22-0.95) | 0.88 (0.28-2.71) | .281 |

| Evolutions in MF, n (%) | 7 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (9) | .106 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0.38 (0.18-0.80) | 0.26 (0.10-0.70) | 0.94 (0.30-2.94) | .069 |

| Evolutions in AL, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| All events, n (%)* | 31 (15) | 20 (11) | 11 (31) | .002 |

| Rate, % pts/y (95% CI) | 2.76 (2.37-3.21) | 1.29 (0.82-2.03) | 3.43 (1.85-6.37) | .010 |

Thrombosis, hemorrhage, or evolution in MF, whichever occurred first.

Although not significant, in the present study, we documented a trend to higher bleeding prevalence in early PMF (9%; rate, 0.88% of patients/year) versus WHO-ET (5%; rate, 0.45% of patients/year). This finding is consistent with the estimates in early PMF of older patients (rate, 1.39% of patients/year in early PMF versus 0.79% of patients/year in WHO-ET).20 Therefore, these data also suggest caution on the use of aspirin in early PMF in young patients. Interestingly, in the reported series of young PVSG-ET patients, the bleeding prevalence ranged between 8.7% and 13%.8,9 The rates of composite outcomes (thrombosis, bleeding, and evolution to overt MF) were significantly higher in early PMF than in WHO-ET patients (3.43% vs 1.29% of patients/year, respectively) and correspond to that observed in older WHO-ET patients (3.24% of patients/year). The higher probability to experience 1 or more events in early PMF was apparent after the first 3-4 years from diagnosis (Figure 1). The event-free survival curves indicate that, after 20 years, almost half of these young people were projected to experience at least 1 of these events compared with 25% of WHO-ET patients. These analyses are limited by the low number (only 35 patients) of early PMF patients, which may affect the precision of the estimates.

Multivariable analysis confirmed that early PMF is an independent risk factor for these cumulative events (hazard ratio = 3.67, P = .003). JAK2 mutational status also emerged as a significant predictor of thrombohemorrhagic events and evolution to myelofibrosis (hazard ratio = 2.70; P = .018). In our study, the limited data on JAK2V617F allele burden, known to predict thrombosis in PVSG-defined ET,21,22 did not allow further analysis. Sex, baseline splenomegaly, previous thrombosis and bleeding, cytoreductive drugs, and aspirin did not influence these outcomes.

In conclusion, among young patients presenting with ET, WHO diagnosis allowed us to recognize a subgroup of early PMF patients who presented with a higher probability of events compared with WHO-ET patients. We speculate that this subgroup may be characterized by a different biology and that the higher rate of events may also be related to a longer disease duration. Practical implications of these findings should be addressed by future studies, but at the present time, we suggest caution in prescribing aspirin and drugs such as anagrelide, which are reported to be associated with an increased risk of evolution toward myelofibrosis, to young, early PMF patients.1

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

A.M.V. and A.R. were supported by a grant from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (Milan, Italy) Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5 × 1000 to the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro–Gruppo Italiano Malattie Mieloproliferative (project no. 1005). A detailed description of the project is available at http://www.progettoagimm.it.

Authorship

Contribution: T.B., J.T., A.C., G.F., and A.T. designed the research, contributed patients, participated in data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript; J.T. reviewed all BM histopathology; F.P., E.R., M.L.R., I.B., A.M.V., H.G., B.G., M.R., F.R., A.R., and N.G. either contributed patients or participated in reviewing BM histopathology; and all authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tiziano Barbui, Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo, Largo Barozzi 1, Bergamo, Italy; e-mail: tbarbui@ospedaliriuniti.bergamo.it.

References

Author notes

T.B., J.T., and A.T. contributed equally to this work.