Key Points

Gata3 is critical for the transition of “double-negative” (DN) thymocyte DN1 to DN2.

Gata3 represses a latent B-cell potential in DN thymocytes.

Abstract

Transcription factors orchestrate T-lineage differentiation in the thymus. One critical checkpoint involves Notch1 signaling that instructs T-cell commitment at the expense of the B-lineage program. While GATA-3 is required for T-cell specification, its mechanism of action is poorly understood. We show that GATA-3 works in concert with Notch1 to commit thymic progenitors to the T-cell lineage via 2 distinct pathways. First, GATA-3 orchestrates a transcriptional “repertoire” that is required for thymocyte maturation up to and beyond the pro–T-cell stage. Second, GATA-3 critically suppresses a latent B-cell potential in pro–T cells. As such, GATA-3 is essential to sealing in Notch-induced T-cell fate in early thymocyte precursors by promoting T-cell identity through the repression of alternative developmental options.

Introduction

T-cell commitment takes place in the thymus, where multipotent hematopoietic precursors sequentially shed their potential to differentiate into non–T-cell lineages while being focused toward becoming a T cell (a process termed “specification”). Thymopoiesis requires continuous replenishment by bone marrow–derived thymus-seeding progenitors that generate early thymic progenitors (ETP) enriched for T-cell potential.1 Several regulatory pathways are involved in early thymocyte differentiation, including Notch signaling and the transcription factors (TFs) GATA-3, Bcl11b, Runx1, Ikaros, c-Myb, and Tcf-1 and the basic helix-loop-helix factors E2A and HEB (for a review, see Rothenberg and Taghon1 ; Chi et al2 ). Nevertheless, the molecular targets for these TFs in developing thymocytes are only poorly characterized, and our knowledge about the potential functional interplay between these different regulatory pathways during T-cell specification is limited.

Notch signals play a decisive role in the T-cell commitment process. T-cell development from hematopoietic precursors requires the expression of Notch-1, interactions with the Notch ligand delta-like 4 (Dll4, expressed by thymic epithelial cells3,4 ), and activation of the Notch canonical signaling cascade.5,6 During T-cell commitment, developing immature CD4-CD8- “double-negative” (DN) thymocytes proceed through phenotypically distinct stages that can be defined using the cell-surface antigens CD25, CD44, and CD117.7,8 Essentially all ETPs reside in the DN1a,b subset that expresses CD1177,9 and requires Notch1 signals to develop.10 While Notch-1/Dll4 interactions are required for T-cell commitment, it is not clear whether Notch-1 signals directly specify T-lineage cells, act to maintain early T-cell progenitors so that their transcriptional program would unfold, and/or suppress alternative cell fates in lymphoid progenitors that are not fully committed. With respect to the latter, there has been much debate about the mechanisms leading to exaggerated B-cell development in the thymus of chimeras generated with Notch-1–deficient hematopoietic stem cells.6 Because ETPs do not develop in this context,10 it is likely that a subset of thymus-seeding progenitors, excluding ETPs,7 can generate thymic B cells in the absence of Notch-1 signals. Studies from 2009 using carboxypeptidase A-Cre transgenic mice (which is active in pro–T cells just downstream of the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) to ETP transition) also demonstrated that Notch-1 ablation in already generated ETPs can results in fate conversion of ETPs to the B-cell lineage.11

There is compelling evidence that a transcriptional program resulting from the sustained ligation of Notch-1 is required for ETPs to differentiate to the DN2 stage and to exclude B-cell and dendritic cell (DC) potential from these early lymphoid progenitors.12,13 T-cell factor 1 (Tcf-1 encoded by Tcf7) is a direct Notch target required for T-cell specification, and overexpression of Tcf-1 can drive T-cell development from progenitors lacking Notch-1 by inducing T-cell signature genes such as GATA-3 and Bcl11b.14,15 Notch signaling is likewise required for Bcl11b induction at the DN2 stage,16,17 suggesting that Notch-1 triggers synergistic activation of key T-cell identity factors. Bcl11b is a known transcriptional repressor that targets protooncogenes (Tal1, Sfpi1, Lyl1, and Erg), cytokine receptors (Kit, Flt3, Il2rb, and Il7r), and natural killer (NK) lineage regulators (Id2 and Nfil3).16,18,19 In the absence of Bcl11b, DN2 cells do not develop into T cells but self-renew or are diverted toward the NK cell lineage.16,17,20 Curiously, both Tcf-1– and Bcl11b-deficient progenitors normally extinguish B-cell potential upon Notch-1 ligation, demonstrating that other mechanisms are involved in this process.

GATA-3 expression is essential for normal T-cell development.21-23 Studies using mice with GATA-3–driven LacZ or GFP reporters enabled developmental mapping of the dynamics of GATA-3 transcriptional activity.23,24 Conditional ablation of GATA-3 expression using mice bearing GATA-3 “floxed” alleles and harboring Lck-Cre or CD4-Cre transgenes demonstrated that GATA-3 was critical for T-cell receptor-β (TCRβ)–selection at the DN to CD4+CD8+ “double positive” (DP) transition and for promoting CD4 lineage choice.25 Less is known about the role for GATA-3 at the earliest stages of T-cell development, as germ line GATA-3–deficiency compromises fetal development and Cre-mediated GATA-3 deletion at the DN1 or DN2 stages has not been performed. Studies using hypomorphic GATA-3 alleles suggest a cell-autonomous role for GATA-3 in ETPs,24 while overexpression of GATA-3 in T-lineage precursors diverts these cells toward the mast cell lineage.26 As such, regulation of GATA-3 expression in early T-cell progenitors is critical.

Both Notch-1 and GATA-3 are required for T-cell specification, but it remains unclear whether they play specific, redundant, or synergistic roles in this process. Here we decipher the role of GATA-3 in the network of transcription factors that program thymopoiesis. We found that GATA-3 controls T-cell development up to and beyond the DN2 stage by regulating transcription factors that promote T-cell identity. In the absence of GATA-3, Notch-triggered T-cell progenitors retain B-cell potential, identifying an unappreciated role for GATA-3 in the suppression of B-cell fate in DN2 thymocytes. These results indicate that GATA-3 promotes T-cell development via complementary feed-forward and alternative fate suppression pathways.

Materials and methods

Gata3−/− fetal liver hematopoietic progenitor cells

C57BL/6 mice carrying 1 Gata3nlslacZ allele23 were mated, and E14.5 embryos were obtained as described in Kaufman et al.27 Mutant embryos were identified by polymerase chain reaction. Hematopoietic chimeras in Rag2−/− or Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice on the Ly5.1 background were generated as described in Samson et al.28 Mice were bred at the laboratory animal facility at the Institut Pasteur, Paris, France, and were provided with food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institut Pasteur and were performed in accordance with French law.

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions from the thymus, spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes were obtained, stained using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) as described in Samson et al.28 FACS analysis was performed on LSR, FACSCanto, FACSCanto II, and LSRFortessa flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Data were analyzed using Flowjo software (TreeStar Inc, San Carlos, CA). The fluorchrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies used for analysis are described in supplemental Table 1. LIVE/DEAD stain (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), DAPI (4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole), or propidium iodide (PI) was used to identify viable cells.

Magnetic-activated and flow cytometric cell sorting

Lineage-positive cells were depleted by using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec, Paris, France) or by using flow cytometric sorting as indicated. The lineage antibodies are indicated in supplemental Table 1. For MACS, lineage-positive cells were depleted by using phycoerythrin- or biotin-conjugated MicroBeads and LS columns (both Miltenyi). DAPI-negative cells were sorted using MoFlo (Cytomation Inc, Fort Collins, CO), FACSAria, or FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson) machines.

Viability assays

For Bcl2 detection, Lin-, CD44+, and c-Kit+ (DN1) and Lin-, CD441, and CD251 (DN2) cells were flow sorted, fixed, and permeabilized using the BD Fix & Perm kit (Becton Dickinson) and stained according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Apoptotic cells were detected using annexin V (Becton Dickinson), and mitochondrial potential was analyzed using 40 nM DiOC6 (3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide, Invitrogen) for 30 minutes at 37°C.

Lymphocyte differentiation in vitro

Unfractionated FL from Gata3+/− or Gata3−/− embryos was cultured on OP9, OP9Δ1, or OP9Δ4 monolayers supplemented with recombinant mouse IL-7 and Flt3L, as described in Schmitt and Zúñiga-Pflücker.29 For limiting dilution analysis, Lin-, CD117+, CD44+, and CD25+ (DN2) cells were FACS-sorted and directly dispensed at 1, 3, and 9 (Gata3−/−) or 10, 30, and 30 (Gata3+/−) cells per well onto OP9 monolayers with the indicated combinations of cytokines. Wells were scored for growth after 1 week, and single-cell clones were phenotyped by FACS. Clonal frequencies were calculated using extreme limiting dilution analysis.30

Transcriptional analysis and TCRβ rearrangements

Molecular profiling was performed on sorted cell populations. RNA was purified (RNeasy kit, Qiagen, Carlsbad, CA), oligo (dT)-primed cDNAs were synthesized using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed using TaqMan primers with detection by an ABI Prism 7000 (Life Technologies, Villebon sur Yvette, France) or a MiniOpticon (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Cognette, France). Primer sequences are available upon request. Genomic DNA was assessed for Dβ1-Jβ1, Dβ2-Jβ2, and Vβ8-Jβ2 rearrangements, as described in Rodewald et al.31

Retroviral production and transduction

The pMXI-EGFP and the pMXI-GATA3-EGFP vectors were previously described in Ferber et al.32 Plasmid DNA was used to transfect Platinum-E cells, and viral supernatants were collected after 48 hours, 0.45µm filtered, and frozen at –80°C. Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cultures were depleted of lineage+ cells using MACS, mixed with half-diluted retroviral supernatant in complete media supplemented with IL-7, Flt3L, and 8 µg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich), and centrifuged onto OP9Δ1 monolayers for 2 hours at 2000 rpm at 32°C. Following overnight culture at 32°C, a second cycle of infection was performed before adding cytokine-containing complete media.

Tat-Cre–mediated Gata3 deletion

Thymocytes from mice bearing floxed Gata3 alleles (Gata3flx/flx33 ) were depleted of CD4-, CD8-, and CD19-expressing cells by using directly conjugated MACS MicroBeads (Miltenyi) and incubated with 2 μM Tat fusion proteins at 37°C for 15 minutes. DN2 thymocytes were sorted and cultured on OP9 stroma, as above. Resultant colonies were phenotyped at day 10 and expanded for DNA analysis. Tat-Cre and Tat-GFP expression plasmids were provided by S. Dowdy, and fusion proteins were prepared as described in Yu et al.34

Results

GATA-3–deficient hematopoeitic precursors seed the thymus

Previous studies of embryonic chimeras made through complementation of wild-type (WT) or Rag2−/− blastocysts with Gata3−/− embryonic stem (ES) cells revealed that Gata3−/− hematopoietic precursors (HPs) did not contribute to thymus reconstitution, thereby explaining the lack of T-cell development, while B cells and other myeloid lineages were generated normally.21,23 In studies from 2009, Gata3−/− HPs showed a variable degree of thymic repopulation, but ETP homeostasis in the thymus was strongly reduced.24 These results suggest that GATA-3 could play a role in thymic ETP migration, similar to the role for GATA-3 in the migration of lymphoid cells to the liver.28

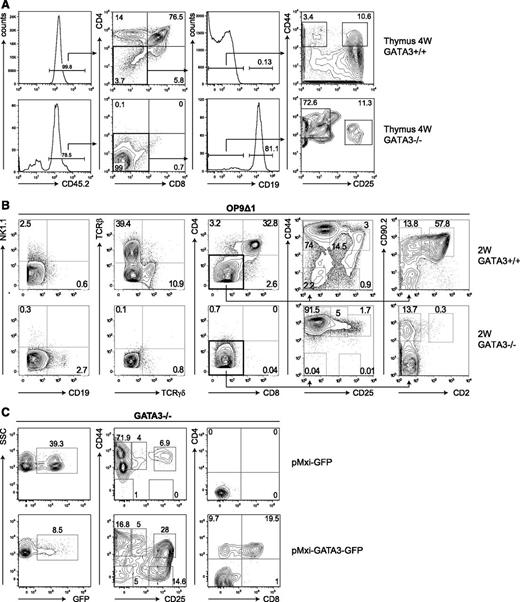

An alternative hypothesis is that resident host elements limit the access of donor-derived Gata3−/− thymus-settling progenitors for thymopoietic “niches.” We compared hematopoietic chimeras made using fetal liver HPs (from embryonic day 14 to 16 donors) bearing heterozygous or homozygous mutant Gata3lacZ alleles23 in Rag2−/− recipients (lacking mature B and T cells) with Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice (also lacking NK cells and their lymphoid precursors). Residual early thymocytes in Rag2−/− mice are 100-fold reduced in the thymus of Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice, thereby providing a more favorable thymic environment.35 Although thymic seeding was observed in Gata3−/− HP chimeras made in Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice (Figure 1A), Gata3−/− precursors were rare in Rag2−/− chimeras (supplemental Figure 1), a finding consistent with previous results3 that suggests that residual Rag2−/− thymic lymphoid precursors could compete with Gata3−/− thymus-settling progenitors. In Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− recipient thymi, an abnormal accumulation of early CD4-CD8- thymocyte precursors with the CD44+CD25- phenotype (DN1 cells) and a smaller subset of CD44+CD25+ cells (DN2) were observed (Figure 1A). DN1 cells in both Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− chimeras expressed equivalent levels of CD117 (c-kit; supplemental Figure 2). These data indicate that GATA-3 is not essential for thymic colonization by HPs, but it is essential for the proper development of early thymocytes up to and beyond the DN2 stage. Interestingly, we observed that donor-derived B cells were increased in the thymi of mice engrafted with Gata3−/− HPs (Figure 1A).

Notch-stimulated Gata3−/− hematopoietic progenitors fail to generate T cells. (A) Flow cytometric analyses were performed on the thymus of chimeras generated by the injection of CD45.2+Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− fetal liver cells into sublethally irradiated CD45.1+Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− recipients. Animals were analyzed 4 weeks after transplantation. All plots are gated on live lymphocytes. (B) Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− fetal liver cells were cultured on OP9 stromal cells expressing the Notch-ligand Dll1 (OP9Δ1) or Dll4 (OP9Δ4) in the presence of IL-7 and Flt3L for 2 weeks. Plots show the expression of the indicated surface markers on live CD45.2+ lymphocytes. (C) Retroviral transduction of Lin-CD117+ precursors from 2-week Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cultures with pMXI-GFP or pMXI-GATA3-GFP retroviral particles. Two weeks after transfection, transduced cells were analyzed for the expression of GFP (left panels). CD45.2+ GFP+ Lin- cells were analyzed for the expression of CD44 vs CD25 (middle panels) and CD4 vs CD8 (right panels), respectively.

Notch-stimulated Gata3−/− hematopoietic progenitors fail to generate T cells. (A) Flow cytometric analyses were performed on the thymus of chimeras generated by the injection of CD45.2+Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− fetal liver cells into sublethally irradiated CD45.1+Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− recipients. Animals were analyzed 4 weeks after transplantation. All plots are gated on live lymphocytes. (B) Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− fetal liver cells were cultured on OP9 stromal cells expressing the Notch-ligand Dll1 (OP9Δ1) or Dll4 (OP9Δ4) in the presence of IL-7 and Flt3L for 2 weeks. Plots show the expression of the indicated surface markers on live CD45.2+ lymphocytes. (C) Retroviral transduction of Lin-CD117+ precursors from 2-week Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cultures with pMXI-GFP or pMXI-GATA3-GFP retroviral particles. Two weeks after transfection, transduced cells were analyzed for the expression of GFP (left panels). CD45.2+ GFP+ Lin- cells were analyzed for the expression of CD44 vs CD25 (middle panels) and CD4 vs CD8 (right panels), respectively.

The in vivo transfer of Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− HPs allowed long-term reconstitution of Rag2−/− and Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− mice to a similar degree (as assessed by bone marrow and splenic cellularity). These chimeric mice harbored donor-derived B cells, myeloid cells, and splenic NK cells, while GATA-3–competent HPs also generated T cells (supplemental Figure 3) in accordance with previous results.18,21,23,28 These results are consistent with earlier reports demonstrating that GATA-3 is largely redundant for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and self-renewal.36

Notch-stimulated T-lineage precursors arrest at the DN2 stage without GATA-3

As the yield of early thymocyte precursors from thymi of GATA-3−/− chimeras was limited, we further characterized these cells by using a stromal cell–based system (OP9Δ1/OP9Δ429 ) that can efficiently recapitulate T-cell development from HPs in vitro (reviewed in Schmitt and Zúñiga-Pflücker37 ). We found that both Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− HPs proliferated extensively when cultured on OP9Δ1 or OP9Δ4 stromal cells in the presence of cytokines (including IL-7, stem cell factor, and Flt3L; similar results were obtained on both OP9Δ1 and OP9Δ4 stroma; data not shown), which confirm previous reports.3,24 While Gata3+/− precursors develop into mature CD3+ T cells (via CD4+CD8+ T-cell intermediates) on OP9Δ cells, the vast majority of cells in Gata3−/− cultures remain at the CD4-CD8- DN stage (Figure 1B). Neither TCRαβ nor TCRγδ cells were present in Gata3−/− OP9Δ cultures, in contrast to WT cultures (Figure 1B). The generation of B cells was inhibited in OP9Δ cultures of Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− HP progenitors (Figure 1A), although significantly more CD19+ B cells were observed in cultures derived from Gata3−/− HPs (Figure 1B). As expected, B cells were readily generated from both WT and Gata3−/− HPs following culture on OP9 stroma (supplemental Figure 4).

We further characterized the DN thymocytes present in these OP9Δ cultures. As expected, Gata3+/− OP9Δ cultures contained immature T cells from all DN stages (Figure 1B) consistent with their capacity to generate TCRαβ and TCRγδ T cells and thymic NK cells.18,29 In contrast, Gata3−/− HPs generated a high proportion of DN1 cells and a clearly defined but less prominent population of CD25+ DN2 cells (Figure 1B). Gata3−/− OP9Δ cultures did not progress beyond the DN2 stage, and despite prolonged culture (>5 weeks), Gata3-deficient DN2 cells failed to accumulate to any appreciable degree (supplemental Figure 5A). Nevertheless, ectopic expression of GATA-3 (using retroviral particles transferring a bicistronic transcript encoding GATA-3 and GFP) was able to rescue the arrested Gata3−/− T-cell precursors present in 2-week OP9Δ cultures and allow their differentiation to the DN3 to DN4 stage and beyond (CD4+CD8+ DP cell stage; Figure 1C). Therefore, the complete developmental arrest in the absence of GATA-3 that occurs at the DN2 stage, where T-cell progenitors normally become committed, can be corrected by Gata3 overexpression. Still, our results clearly demonstrate a role for Gata3 in the generation of early thymocyte progenitors and in the DN1 to DN2 transition.

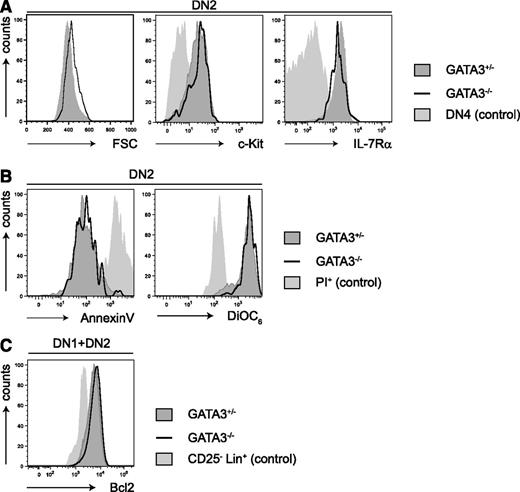

Characterization of GATA-3–deficient DN2 cells

We found that the growth factor receptors CD117 (c-kit) and CD127 (IL-7Rα) were normally expressed on DN2 cells in the absence of GATA-3 (Figure 2A). Previous reports demonstrated normal annexin V staining and a higher proliferation in c-kit+DN1 cells from day 4 Gata3−/− OP9Δ cultures,24 a result that we confirmed (supplemental Figure 6). We found that Gata3−/− DN2 cells exhibited normal annexin V binding and DiOC6 staining compared with WT cells (Figure 2B), and expression levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 were comparable between GATA-3–competent and GATA-3–deficient precursors (Figure 2C). Taken together, the apparently normal survival of Gata3−/− DN2 cells suggests that GATA-3 plays a role in the DN1 to DN2 transition that generates and expands early thymocyte precursors.

GATA-3-deficiency does not influence the survival of DN2 T-cell precursors. (A) The graphs show flow cyotmetric analysis of forward scatter, c-Kit, and IL-7Rα expression on CD44+CD25+CD4-CD8- “double negative 2” (DN2) subsets of Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cocultures after 2 weeks. Filled histograms indicate Gata3+/− cells, and solid lines indicate Gata3−/− cells. DN4 cells served as controls (light gray histograms). (B) DN2 cells were analyzed for annexin V binding (apoptosis) and DiOC6 staining. Filled histograms indicate Gata3+/− cells, and solid lines indicate Gata3−/− cells. PI+ cells were used as controls (light gray histograms). (C) DN1 and DN2 cells were analyzed for intracellular Bcl2 expression. Filled histograms indicate Gata3+/− cells, and solid lines indicate Gata3−/− cells. Lin-CD25+ cells were used as a negative control (light gray histogram).

GATA-3-deficiency does not influence the survival of DN2 T-cell precursors. (A) The graphs show flow cyotmetric analysis of forward scatter, c-Kit, and IL-7Rα expression on CD44+CD25+CD4-CD8- “double negative 2” (DN2) subsets of Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cocultures after 2 weeks. Filled histograms indicate Gata3+/− cells, and solid lines indicate Gata3−/− cells. DN4 cells served as controls (light gray histograms). (B) DN2 cells were analyzed for annexin V binding (apoptosis) and DiOC6 staining. Filled histograms indicate Gata3+/− cells, and solid lines indicate Gata3−/− cells. PI+ cells were used as controls (light gray histograms). (C) DN1 and DN2 cells were analyzed for intracellular Bcl2 expression. Filled histograms indicate Gata3+/− cells, and solid lines indicate Gata3−/− cells. Lin-CD25+ cells were used as a negative control (light gray histogram).

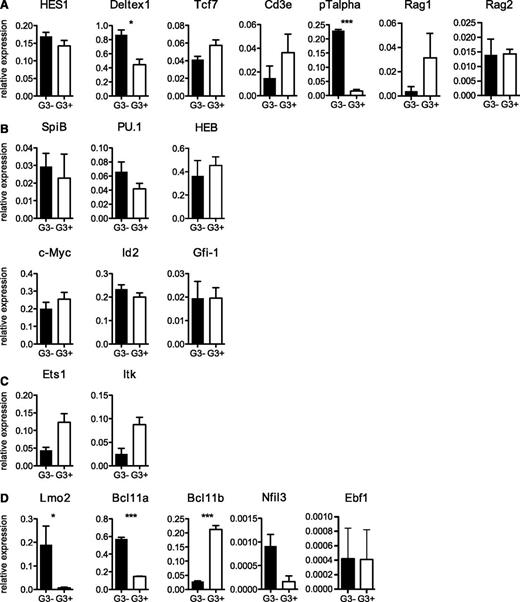

We next analyzed the molecular profiles of Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− DN2 cells (Figure 3). Both types of DN2 cells were clearly differentiated toward the T-cell lineage and expressed transcripts for Ptcra, Cd3e, and, importantly, Tcf7 (encoding TCF-1), which is critical for T-lineage specification and differentiation.15 Notch-stimulated targets that are expressed in DN2 cells include Tcf7, Ptcra, Hes1, and Deltex1;13 all are clearly expressed in DN2 cells in the absence of GATA-3, further confirming the T-cell profile of Gata3−/− DN2 cells.

Transcriptional analysis of Gata3−/− DN2 T-cell progenitors. (A-D) Quantitative RT-PCR for the indicated genes in sorted DN2 populations from Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cultures is shown as expression levels relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression levels. *P < .05; ***P < .001.

Transcriptional analysis of Gata3−/− DN2 T-cell progenitors. (A-D) Quantitative RT-PCR for the indicated genes in sorted DN2 populations from Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− OP9Δ1 cultures is shown as expression levels relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase expression levels. *P < .05; ***P < .001.

Numerous transcription factors are dynamically regulated during early thymocyte differentiation (reviewed in Rothenberg et al38 ). Although the expression of most transcription factor changes gradually during development from ETP to DN2 (such as Notch1, GATA-3, Tcf-1, and Gfi1), Bcl11b, LEF1, and HEBalt levels are dramatically upregulated, and PU.1, Tal1, Lyl1, and Bcl11a are downregulated during this transition (reviewed in Rothenberg et al38 ). We found that GATA-3 was apparently not involved in the regulation of many of these TFs in DN2 cells, including PU.1, HEB, Gfi1, and Tcf7 (Figure 3A-C). We also found that the levels of SpiB (critical for DC development) and the transcriptional repressor Id2 (critical for NK cell development) were unaltered in the absence of Gata-3 (Figure 3B-C). c-Myc expression is upregulated in mice that are overexpressing GATA-3 at the DP stage,39 but we did not observe changes in Myc expression in Gata3−/− DN2 cells. In contrast, Ets1 and Bcl11b expression levels were clearly reduced in the absence of GATA-3. While Ets-1 targets are poorly defined, Bcl11b has been shown to play an essential role in T-cell commitment by repressing alternative (myeloid and NK cell) fates in DN1 and DN2 cells.16,17,20 Along these lines, we found that Nfil3 expression (required for NK cell development and normally repressed by Bcl11b17 ) was upregulated in Gata3−/− DN2 cells. The expression levels of B-cell factors in DN2 cells were at (Ebf1) or below (Pax5) detection levels and were not altered in Gata3−/− DN2 cells (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 7). Interestingly, 2 additional TFs (Lmo2 and Bcl11a) were clearly upregulated in the absence of GATA-3 (Figure 3D). Both Bcl11a and Lmo2 are highly expressed in multilineage progenitors, and their overexpression can lead to lymphoid cell malignancies.41,42 These results demonstrate that GATA-3 is essential for Notch-1–induced T-cell differentiation up to and beyond the DN2 stage, which is a process that involves multiple TFs (Ets1, Bcl11b).

While Gata3−/− DN2 cells showed evidence of Notch-mediated transcriptional activation, Ptcra (pTα) and Deltex1 overexpression (Figure 3A) led us to consider that excessive Notch stimulation might paradoxically block T-cell development in Gata3−/− OP9Δ cultures. We tested this hypothesis by culturing Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− HPs on OP9 stromal cells bearing the Notch ligands Jagged 1 (OP9J1) or Jagged 2 (OP9J2) and compared them with OP9Δ1 or OP9Δ4. Jagged proteins can interact with Notch receptors on early lymphoid precursors, but their capacity to promote T-cell differentiation (and suppress B-cell differentiation) in vitro is reduced compared with Dll1 or Dll4.43 OP9J1 and OP9J2 cultures were permissive for B-cell development from both Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− HPs (albeit less efficient than parental OP9 cells), but only OP9J2 cells allowed the generation of CD3+ T cells, and this only occurred from Gata3+/− HPs (supplemental Figure 8). These results are consistent with a hierarchy in potency of Notch ligands for promoting T-cell development (Dll1 and Dll4 > Jagged 2 > Jagged 1) that corresponds to their efficiency in suppressing B-cell development in this culture system, as previously reported by Van de Walle et al.44 Nevertheless, none of these OP9 stromal lines supported the development of CD3+ T cells from Gata3−/− HPs, suggesting that excessive Notch signaling was not toxic for early thymocytes in the absence of GATA-3.

GATA-3–deficient DN2 cells possess an abnormal B-cell potential

Thymic DN2 cells are highly enriched in T-cell progenitors, completely lack B-cell potential, and maintain a latent NK cell potential that is lost after productive TCRβ gene rearrangement at the DN3 stage.7-9,14 Because Gata3−/− OP9Δ cultures did not generate T cells, we assessed whether mutant DN2 cells harbored NK cell precursors. To test their developmental potential, we isolated Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− DN2 cells and cultured them on OP9 stroma (thereby releasing them from enforced Notch stimulation) with or without IL-2. Robust growth was observed from both Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− DN2 cells with indistinguishable colony burst sizes, and limiting dilution analysis indicated a clonal growth frequency of about 1 in 3.5 cells (Figure 4A; Table 1). Analysis of the single-cell colonies showed that Gata3+/− DN2 cells generated (as expected) exclusively NK cell clones, irrespective of the presence of IL-2 (108 single cell wells seeded, giving rise to 11 colonies). Surprisingly, about 50% of the Gata3−/− DN2 cells generated B-cell clones (144 single cell wells seeded, giving rise to 19 colonies) in the presence of IL-2 (Figure 4B). The B-cell potential of Gata3−/− T-cell precursors was more apparent in the absence of IL-2, where single Gata3−/− DN2 cells generated almost exclusively B cells (144 single cell wells seeded, giving rise to 23 colonies), with rare precursors giving rise to both B and NK cells (Figure 4B, lower left panel). The B-cell potential of Gata3−/− DN2 cells was not due to a subset of cells that were already committed to the B-cell lineage, because mutant DN2 precursors did not express transcripts for the B-cell–specific genes EBF or Pax-5 (Figure 3D; supplemental Figure 7). In contrast, CD19+IgM+ B cells derived from Gata3−/− DN2 cultures (Figure 4C) expressed Ebf1 and Pax5 similar to normal splenic B cells (Figure 4D). Therefore, a latent B-cell potential in DN2 cells was only revealed when the cells were removed from Notch signaling, and only in the absence of GATA-3.

Clonal frequency analysis of DN2 cells

| . | B . | NK . | Myeloid . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GATA3+/− DN2 (OP9) | |||

| IL-2 | ND | 2.85 (2.31-3.53) | ND |

| IL-7 + Flt3L | ND | 5.33 (4.24-6.70) | ND |

| GM-CSF + IL-4 | ND | ND | ND |

| GATA3−/− DN2 (OP9) | |||

| IL-2 | 11.24 (8.47-14.91) | 12.79 (9.51-17.21) | ND |

| IL-7 + Flt3L | 6.57 (5.17-8.35) | 77.46 (40.18-149.32) | ND |

| GM-CSF + IL-4 | 9.56 (6.25-14.6) | 11.49 (5.48-24.1) | 4915 (691-34 948) |

| . | B . | NK . | Myeloid . |

|---|---|---|---|

| GATA3+/− DN2 (OP9) | |||

| IL-2 | ND | 2.85 (2.31-3.53) | ND |

| IL-7 + Flt3L | ND | 5.33 (4.24-6.70) | ND |

| GM-CSF + IL-4 | ND | ND | ND |

| GATA3−/− DN2 (OP9) | |||

| IL-2 | 11.24 (8.47-14.91) | 12.79 (9.51-17.21) | ND |

| IL-7 + Flt3L | 6.57 (5.17-8.35) | 77.46 (40.18-149.32) | ND |

| GM-CSF + IL-4 | 9.56 (6.25-14.6) | 11.49 (5.48-24.1) | 4915 (691-34 948) |

Gata3+/− and Gata3−/− DN2 precursors were cocultured with OP9 stroma under the indicated conditions and analyzed after 2 weeks.

Values represent frequencies (1/x) with 95% confidence intervals. Frequencies were calculated according to Hu and Smyth.30

ND, not detected.

Lymphoid potential of Gata3−/− DN2 T-cell progenitors. (A) The graph shows limiting dilution and clonal frequency analysis of Gata3−/− and Gata3+/− DN2 cells (sorted from OP9Δ1 cultures) following replating on OP9 stroma in the presence of IL-7, Flt3L, and IL-2. Wells were scored for growth after 1 week. (B) Clones derived from single Gata3−/− and Gata3+/− DN2 cells after reculture on OP9 stroma with IL-2 (upper panels) or without IL-2 (lower panels) were analyzed for the expression of NK1.1 and CD19. (C) Gata3−/− DN2 cells were recultured on OP9 stroma with IL-7, and NK1.1- lymphocytes were analyzed for the expression of CD19 and IgM. The gate indicates the population that was sorted for analysis of transcripts (D). (D) RT-PCR analysis shows the expression of B- and T-cell transcription factors by B cells grown from sorted DN2 cells on OP9 stroma (DN2 > B, as shown in [C]) compared with sorted splenic B (B) and T (T) lymphocytes from a C57BL/6 control mouse. (E) Gata3−/− T-cell precursors were retrovirally transduced with pMXI-GATA3-GFP, and single GFP- or GFP+ DN2 cells were cultured on either OP9 (upper panels) or OP9Δ1 (lower panels) stroma with IL-7 and Flt3L. One week later, plates were scored for growth, and the colonies derived from a single DN2 were stained for NK1.1, CD3, or CD19 expression, as indicated.

Lymphoid potential of Gata3−/− DN2 T-cell progenitors. (A) The graph shows limiting dilution and clonal frequency analysis of Gata3−/− and Gata3+/− DN2 cells (sorted from OP9Δ1 cultures) following replating on OP9 stroma in the presence of IL-7, Flt3L, and IL-2. Wells were scored for growth after 1 week. (B) Clones derived from single Gata3−/− and Gata3+/− DN2 cells after reculture on OP9 stroma with IL-2 (upper panels) or without IL-2 (lower panels) were analyzed for the expression of NK1.1 and CD19. (C) Gata3−/− DN2 cells were recultured on OP9 stroma with IL-7, and NK1.1- lymphocytes were analyzed for the expression of CD19 and IgM. The gate indicates the population that was sorted for analysis of transcripts (D). (D) RT-PCR analysis shows the expression of B- and T-cell transcription factors by B cells grown from sorted DN2 cells on OP9 stroma (DN2 > B, as shown in [C]) compared with sorted splenic B (B) and T (T) lymphocytes from a C57BL/6 control mouse. (E) Gata3−/− T-cell precursors were retrovirally transduced with pMXI-GATA3-GFP, and single GFP- or GFP+ DN2 cells were cultured on either OP9 (upper panels) or OP9Δ1 (lower panels) stroma with IL-7 and Flt3L. One week later, plates were scored for growth, and the colonies derived from a single DN2 were stained for NK1.1, CD3, or CD19 expression, as indicated.

In order to test if the repression of a latent B-cell potential in DN2 cells relied on GATA-3 expression, Gata3−/− DN2 cells were infected with the GATA-3–containing retrovirus, and B-, T-, and NK-cell potential was assessed from GFP+ (GATA-3–transduced) and GFP- (control) cells. GATA-3 expression in Gata3−/− DN2 cells restored T-cell potential upon culture on OP9Δ and allowed NK cell development on OP9 stromal cells (Figure 4D). The latent B-cell potential in Gata3−/− DN2 cells was therefore inhibited by GATA-3.

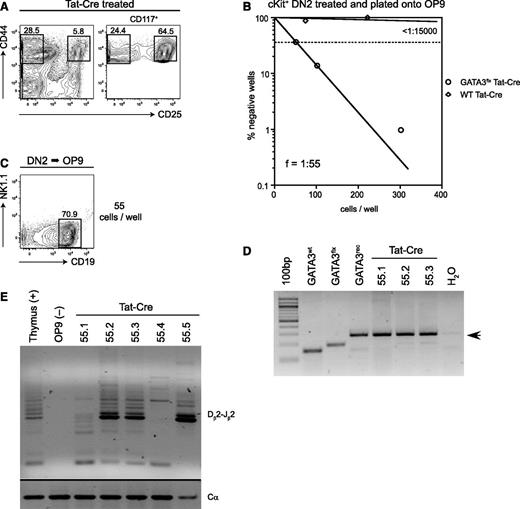

Inducible GATA-3 deletion in WT DN2 thymocytes unmasks a latent B-cell potential

The unexpected B-cell potential observed in Gata3−/− DN2 cells might result from their prolonged in vitro culture. We therefore isolated bone fide DN2 thymocytes from mice bearing a conditional GATA-3 allele (Gata3flx/flx33 ), induced GATA-3 deletion in these cells by using a soluble form of the Cre recombinase (Tat-Cre), and cultured them on OP9 stroma. As expected ,7-9,14 DN2 cells (Figure 5A-B) from control thymi or from Tat-GFP–treated GATA-3flx/flx thymi gave rise to few colonies under these conditions (clonal frequency < 1 in 7000; Figure 5B), consisting mostly of NK1.1+ NK cells (data not shown). In contrast, conditional ablation of GATA-3 expression in DN2 thymocytes using Tat-Cre completely abolished T-cell development (0/144 clones tested; data not shown) and resulted in dramatically increased B-cell clonal frequencies (ƒ = 1/55; Figure 5B). DNA from these DN2-derived B-cell colonies (Figure 5C) bore recombined (deleted) GATA-3 alleles (Figure 5D). Furthermore, these Gata3−/− DN2-derived B-cell colonies harbored distinct TCR-Dβ2-Jβ2 rearrangements (Figure 5E), which are molecular markers that characterize T-cell progenitors, and which are not observed in B cells under normal conditions. These results using Gata3flx/flx mice confirm the essential role of GATA-3 in early committed T-cell progenitors to limit B-cell potential.

Conditional ablation of Gata3 in DN2 cells reveals their B-cell potential. (A) CD44 vs CD25 expression on Tat-Cre–treated CD117+ thymocytes derived from Gata3flx/flx mice are shown. Sort gates used to isolate CD44+CD25+ DN2 cells are indicated. (B) The graph shows limiting dilution and clonal frequency analysis of CD117+ DN2 cells from WT and Gata3flx/flx thymocytes after treatment with Tat-Cre and plating on OP9 stroma in the presence of IL-7 and Flt3L. Colony growth was scored at 1 week. (C) The representative B-cell colony results from the culture of Tat-Cre–treated Gata3flx/flx DN2 thymocytes (55 cells per well plated). (D) Molecular analysis of the Gata3 locus in CD19+ B-cell colonies was derived following conditional Gata3 ablation in DN2 thymocytes. (E) The analysis of TCR-Dβ2-Jβ2 rearrangements in B-cell colonies after the culture of Tat-Cre–treated Gata3flx/flx DN2 thymocytes is shown. DNA from the total thymus was used as a positive control, and OP9 stroma DNA was used as a negative control.

Conditional ablation of Gata3 in DN2 cells reveals their B-cell potential. (A) CD44 vs CD25 expression on Tat-Cre–treated CD117+ thymocytes derived from Gata3flx/flx mice are shown. Sort gates used to isolate CD44+CD25+ DN2 cells are indicated. (B) The graph shows limiting dilution and clonal frequency analysis of CD117+ DN2 cells from WT and Gata3flx/flx thymocytes after treatment with Tat-Cre and plating on OP9 stroma in the presence of IL-7 and Flt3L. Colony growth was scored at 1 week. (C) The representative B-cell colony results from the culture of Tat-Cre–treated Gata3flx/flx DN2 thymocytes (55 cells per well plated). (D) Molecular analysis of the Gata3 locus in CD19+ B-cell colonies was derived following conditional Gata3 ablation in DN2 thymocytes. (E) The analysis of TCR-Dβ2-Jβ2 rearrangements in B-cell colonies after the culture of Tat-Cre–treated Gata3flx/flx DN2 thymocytes is shown. DNA from the total thymus was used as a positive control, and OP9 stroma DNA was used as a negative control.

Discussion

Here we analyze the role for the transcription factor GATA-3 in T-cell specification and lineage commitment. Using a combination of in vivo reconstitution and in vitro differentiation from Gata3−/− hematopoietic precursors, we demonstrate that GATA-3 plays a critical role in the generation of CD25+ pro–T cells by regulating the TF “repertoire” required for further T-cell differentiation. We also found that GATA-3, beyond its role as a catalyst of T-cell lineage development, plays a critical role as a negative regulator of B-cell fate in ETPs. In the absence of GATA-3, pro–T cells retained B-cell potential, which could be demonstrated by using in vitro–derived Gata3−/− cells or, in vivo, by the conditional deletion of Gata3 in CD25+ DN2 thymocytes. Taken together, these results suggest that GATA-3 promotes T-cell fate in 2 ways: by synergizing with the Notch-initiated T-cell program and by extinguishing alternative lymphoid cell fates.

Germ-line GATA-3 ablation results in prenatal mortality around embryonic day 11 (E11) due to the lack of noradrenalin synthesis.22 Administration of α- and β-adrenergic receptor agonists can rescue Gata3−/− embryos (up to E1827 ), and we and others have used this approach to study the role for GATA-3 in early thymopoiesis.18,24,45 These studies provided clear evidence for an essential role of GATA-3 in the generation of early T-cell progenitors. Thymus seeding by Gata3−/− precursors was demonstrable in vivo, although greatly reduced in irradiated congenic hosts,24 and most thymic progenitors were blocked at the DN1/ETP stage.24 Use of the conditional Gata-3 deletion in hematopoietic cells (Vav1Cre × Gata-3flx/flx mice) generated similar results, and the transfer of Gata-3-deficient precursors to fetal thymic organ culture or in vitro culture on OP9 stromal cells expressing Dll1 recapitulated the in vivo results.24,45 While Gata3−/− ETPs did not appear to have defective survival characteristics, their transcriptional profiles were not studied. Here we have performed an extensive molecular and function analysis of Gata3−/− CD25+ DN2 cells.

The DN2 stage of thymocyte development represents a critical step in T-cell specification and commitment. DN2 cells are highly enriched in T-cell potential, but they are not fully restricted to the T-cell lineage, because they may still give rise to NK cells and DCs when given the appropriate conditions. In contrast, DN2 cells lack demonstrable B-cell potential.7-9 The DN2 cell fate is associated with a transcription factor repertoire that reflects the ongoing specification and commitment to the T-cell lineage. This includes the increasing expression of Tcf-1, HEB, Gfi-1, Bcl11b, and Gata-3, while PU.1, Lmo2, Bcl11a, Tal1, and Lyl1 are extinguished (reviewed in Rothenberg et al38 ). DN2 cells also express T-cell–specific genes (Ptcra and CD3 components) and engage the recombination machinery required for the generation of pre-TCR and TCRγδ T-cell receptors.

A detailed analysis of the GATA-3 binding sites that are present during early thymocyte precursor differentiation was reported in 2012.46 GATA-3 sites were identified that were not associated with histone methylation or acetylation marks, but they were clearly dependent on the stage of T-cell differentiation.46 Comparing our results of Gata3−/− DN2 cells to this genomewide GATA-3 binding site analysis reveals interesting points. First, Gata3−/− DN2 cells showed clear evidence of T-cell specification with the expression of “signature” genes (Ptcra, Lck, Zap70, and CD3e). While the Notch1 targets Ptcra and Deltex1 were overexpressed without GATA-3, these genes do not bind GATA-3;46 how Notch signaling is released from GATA-3 inhibition therefore remains unclear. Second, the absence of GATA-3 did not alter the expression of HEB, Gfi1, c-kit, and Tcf1, which have previously been associated with defects in the DN1 to DN2 transition. Because Gfi1, HEB, and Tcf-1 bear GATA-3 binding sites,46 a GATA-3–independent mechanism for their activation must exist. Third, a normal unfolding of the T-lineage program, including the upregulation of Tcf-1 and the downregulation of PU.1,47 occurs normally in Gata3−/− DN2 cells. Finally, the expression levels of several critical T-cell factors (Bcl11b, Ets-1, and Rag1) were GATA-3 dependent and consistent with GATA-3 binding to these targets.46 While the role of Bcl11b in repressing alternative cell fates (ie NK cells) in pro–T cells is now well recognized,16,17,20 the molecular mechanism by which Bcl11b promotes the completion of T-cell specification is not understood. One hypothesis is that Bcl11b works by ensuring high E protein activity that sustains the DN2 to DN3 transition.38 In this way, GATA-3 may indirectly control the E protein levels that are required for successful T lymphopoiesis in addition to a possible direct regulation of E2A and HEB via GATA-3 binding.46 Ets-1 and Rag1 are generally involved at the DN3 stage, but Ets-1 may have earlier roles in DN thymocytes.40 GATA-3 is therefore an essential factor for the further differentiation of DN2 cells.

We discovered an unexpected role for GATA-3 development in repressing the development of other hematopoietic cell fates, especially B cells, in early thymocytes. We found that significantly more B cells developed from Gata3−/− precursors in vivo and even in vitro in the presence of the Notch ligands Dll1 or Dll4. Gata3−/− DN2 cells, which showed ample evidence of sustained Notch signaling, were still capable of “reverting” to the B-cell lineage, while this B-cell potential was extinguished in Gata3+/− DN2 cells. Moreover, inducible GATA-3 deletion in DN2 thymocytes unleashed their B-cell potential. Taken together, these different results strongly implicate GATA-3 in the suppression of a latent B-cell potential in CD25+ pro–T cells.

While Gata3−/− DN2 cells showed robust B-cell development, NK cell or myeloid cell development from these cells was demonstrable but not appreciably augmented. The paucity of NK cell development was somewhat surprising given the reduction in Bcl11b that can repress NK cell lineage commitment.16,17 Still, the ability of the Bcl11b deletion to promote NK cell “conversion” has only been demonstrated in a GATA-3–competent context. This may be critical as GATA-3 has a documented role in the development of bone marrow and thymic NK cells.18,28 Some myeloid development was observed from Gata3−/− DN2 cells (4 of 78 clones tested) that mainly make up CD11c+ DCs. As PU.1 (and SpiB) expression levels were not elevated in Gata3−/− DN2 cells, GATA-3 does not play a major role in antagonizing PU.1. Collectively, our results demonstrate that a Gata-3 deficiency selectively promotes a latent B-cell potential in DN2 cells.

Signatures of B-lineage specification, such as EBF and Pax5, are not normally expressed in DN2 cells, and we found no evidence of their upregulation in Gata3−/− DN2 cells. Tcf-1 appears redundant for the repression of B-cell potential from early thymocyte progenitors,15 and while Bcl11b acts to suppress alternative cell fates, there is no evidence for B-cell conversion from Bcl11b−/− DN2 cells.16 Interestingly, GATA-3 expression is preserved in Tcf7−/− or Bcl11b−/− thymic progenitors, consistent with the role for GATA-3 in B-cell fate repression. We observed a clear upregulation of Bcl11a in Gata3−/− DN2 cells. Bcl11a has multiple roles in the hematopoietic system; its overexpression can confer a myeloid phenotype, while its absence is associated with defective B-cell development.42 Bcl11a is normally downregulated by the DN2 stage,38 and its loss is coincident with the onset of T-cell specification. Because the absence of Notch111 or Gata-3 (as in this work) promotes B-cell fate conversion, it will be interesting to know if Bcl11a levels remain elevated in the absence of Notch-1 signals.

Previous studies suggested that Gata-3 expression in early T-cell progenitors in mice might be regulated by Notch1 signals,48 although not in humans.49,50 Tcf-1 may regulate GATA-3 expression as levels are reduced in Tcf7−/− T-cell progenitors.15 The combined actions of Notch1, Tcf-1, and Gata-3 result in a synergistic activation of Bcl11b that is required for T-cell commitment (supplemental Figure 9). Our analysis of Gata3−/− DN2 cells additionally suggests that Gata-3 represses “stem cell–like” genes (including Lmo2) that are highly expressed in immature lymphoid progenitors, associated with T-cell transformation,41 and normally downregulated by the DN2 stage. The ability of GATA-3 to promote T-cell lineage development via the extinction of stem cell qualities and the repression of B-cell fate parallels that of Bcl11b, which inhibits the NK cell fate. In this way, these 2 critical T-cell transcription factors have the ability to extinguish “stemness” and to protect DN2 cells from diversion into alternative hematopoietic lineages (supplemental Figure 9).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S. Samson for advice on embryo isolation, G. Masse for helpful discussions regarding retroviral transductions, and S. Dowdy for providing the Tat-Cre and Tat-GFP expression plasmids.

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Pasteur Foundation (M.E.G.-O.), by grants from the Huygens Scholarship Program and the Royal Netherlands Academy for Arts and Sciences (both the Netherlands) and by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (France; R.G.J.K.W.). This work was also supported by grants from the Institut Pasteur, the Inserm, and the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (all in France; J.P.D.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.E.G.-O. and R.G.J.K.W. designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. F.L., O.R.-L.G., M.H., and A.C. performed experiments and analyzed data. R.W.H. provided critical reagents and wrote the manuscript. J.P.D. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for M.E.G.-O. is School of Natural Sciences, University of California–Merced, Merced, CA.

Correspondence: James P. Di Santo, Innate Immunity Unit, Institut Pasteur, 25 rue du Docteur Roux, 75724 Paris, France; e-mail: james.di-santo@pasteur.fr.

References

Author notes

M.E.G-O., R.G.J.K.W., and F.L. contributed equally to this work.

![Figure 4. Lymphoid potential of Gata3−/− DN2 T-cell progenitors. (A) The graph shows limiting dilution and clonal frequency analysis of Gata3−/− and Gata3+/− DN2 cells (sorted from OP9Δ1 cultures) following replating on OP9 stroma in the presence of IL-7, Flt3L, and IL-2. Wells were scored for growth after 1 week. (B) Clones derived from single Gata3−/− and Gata3+/− DN2 cells after reculture on OP9 stroma with IL-2 (upper panels) or without IL-2 (lower panels) were analyzed for the expression of NK1.1 and CD19. (C) Gata3−/− DN2 cells were recultured on OP9 stroma with IL-7, and NK1.1- lymphocytes were analyzed for the expression of CD19 and IgM. The gate indicates the population that was sorted for analysis of transcripts (D). (D) RT-PCR analysis shows the expression of B- and T-cell transcription factors by B cells grown from sorted DN2 cells on OP9 stroma (DN2 > B, as shown in [C]) compared with sorted splenic B (B) and T (T) lymphocytes from a C57BL/6 control mouse. (E) Gata3−/− T-cell precursors were retrovirally transduced with pMXI-GATA3-GFP, and single GFP- or GFP+ DN2 cells were cultured on either OP9 (upper panels) or OP9Δ1 (lower panels) stroma with IL-7 and Flt3L. One week later, plates were scored for growth, and the colonies derived from a single DN2 were stained for NK1.1, CD3, or CD19 expression, as indicated.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/10/10.1182_blood-2012-06-440065/4/m_1749f4.jpeg?Expires=1765884598&Signature=Reo8AYfTaC5Tf8pGF06jnD0VA891B0hx4oCzUGNJ~Q-g~dohOyy0jXn1rJa4KmouupctNJs-wMXIst5vEYKSnOr0gEWO0XplCZsbn2-L3SBNn5RByHf8cXdDii~G0~tudzo57DqfOEJKVO0jM1xdECkQp~83DeExXviatrzE6SG-bX6tV9UXbuJLS0IwRjsBLjrVt-NO9g81GXHd936UPNkmIxt34weQjvpWyefgvpZo6ORHEVvS7cZeSh2WKX6yayb~I1l6R~1qWNeTvuF3QsAmvgc4QBdBkOgeP8p0RJW0J2YKpn5MypFBx7AALcRoSH~mguqXjO57UHbdDEHgsA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal