Key Points

Mutations in PRKCD cause a syndrome characterized by chronic benign lymphadenopathy, positive autoantibodies, and NK dysfunction.

PRKCD deficiency disrupts control of B-cell proliferation and apoptosis and affects NK-cell cytolytic activity.

Abstract

Defective lymphocyte apoptosis results in chronic lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly associated with autoimmune phenomena. The prototype for human apoptosis disorders is the autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), which is caused by mutations in the FAS apoptotic pathway. Recently, patients with an ALPS-like disease called RAS-associated autoimmune leukoproliferative disorder, in which somatic mutations in NRAS or KRAS are found, also were described. Despite this progress, many patients with ALPS-like disease remain undefined genetically. We identified a homozygous, loss-of-function mutation in PRKCD (PKCδ) in a patient who presented with chronic lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, autoantibodies, elevated immunoglobulins and natural killer dysfunction associated with chronic, low-grade Epstein-Barr virus infection. This mutation markedly decreased protein expression and resulted in ex vivo B-cell hyperproliferation, a phenotype similar to that of the PKCδ knockout mouse. Lymph nodes showed intense follicular hyperplasia, also mirroring the mouse model. Immunophenotyping of circulating lymphocytes demonstrated expansion of CD5+CD20+ B cells. Knockdown of PKCδ in normal mononuclear cells recapitulated the B-cell hyperproliferative phenotype in vitro. Reconstitution of PKCδ in patient-derived EBV-transformed B-cell lines partially restored phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate–induced cell death. In summary, homozygous PRKCD mutation results in B-cell hyperproliferation and defective apoptosis with consequent lymphocyte accumulation and autoantibody production in humans, and disrupts natural killer cell function.

Introduction

Protein kinase C (EC 2.7.11.13), also known as PKC, is a family of serine/threonine kinases that play a key role in the regulation of various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation.1,2 In humans, at least 11 different PKC polypeptides have been identified. On the basis of their requirements, the PKC family is divided in 3 subfamilies as follows: the conventional PKCs (cPKC; α, βI, βII, and γ), the novel PKCs (nPKC; δ, ε, η, and θ) and the atypical PKCs (aPKC; ζ and λ/i). nPKCs require diacylglycerol (DAG) but not calcium (Ca2+) for activation. Specifically, PKCδ (OMIM 176977, also known as PKCD, PRKCD) is activated via DAG produced by receptor-mediated hydrolysis of membrane inositol phospholipids as well as by phorbol ester. Numerous studies in humans and mice have shown that PKCδ has important roles in B-cell signaling and autoimmunity, as well as regulation of growth, apoptosis, and differentiation of a variety of cell types.1-6 Interestingly, mice homozygous for a null allele of the gene that encodes PKCδ, PRKCD (National Center for Biotechnology Information gene ID 5580), exhibit some of the signs of the autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS; OMIM 601859),7 including autoimmunity, neutropenia, and increased B-cell numbers and proliferation,3 making PKCδ an appealing candidate gene for humans with ALPS-like disease.

In this study we identified a homozygous PKCδ loss-of function mutation in a patient with autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, and chronic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Our results establish PKCδ as a key protein regulating B-cell proliferation and tolerance as well as NK function in humans.

Materials and methods

All patients or their guardians provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under institutional review board−approved protocols of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Blood from healthy control patients was obtained under approved protocols of these centers.

Cell lines and culture

EBV-transformed B-cell lines derived from patients and normal donors were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco), 2mM L-glutamine, penicillin 100 U/mL, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by the use of Ficoll separation (Lonza). Human B cells were purified by negative selection by use of the StemSep Human B-cell Enrichment kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (StemCell Technologies). PBMCs were cultured in 10% complete media as stated previously.

DNA sequencing and bioinformatics methods

The patient’s genomic DNA was submitted to Otogenetics for whole exome capture (Agilent V4; 51 Mbp) and next-generation sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq2000. Sanger DNA sequencing was performed with the use of purified polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products amplified by PRKCD exon−specific primers and GoTaq Hot Start Polymerase (Promega); PCR products were directly sequenced with BigDye Terminators (version 1.1) and analyzed on a 3130xL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

The DNAnexus interface was used to align the Illumina reads to the hg19 human reference genome and perform SNP and INDEL discovery and genotyping. To prioritize the 37 950 variant calls, we implemented the ANNOVAR functional annotation package8 and filtered the output on the basis of gene/amino acid annotation, functional prediction scores (SIFT, PolyPhen, LRT, MutationTaster), conservation scores (PhyloP and GERP++), and allele frequencies per the National Center for Biotechnology Information dbSNP database (build 132), The 1000 Genomes Project (2011 May release), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project (ESP5400). Only nonsynonymous novel variants or variants with population frequencies <1% were considered further. Variants in segmental duplication regions also were excluded. Exomic variants were finally prioritized on the basis of clinical correlation.

Immunohistopathology

Anti-PKCδ stains were performed on FFPE samples with a reactive tonsil as positive control. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded-alcohol, placed in a hot 1× low pH antigen retrieval solution (Dako, S1699), and microwaved for 6 minutes. Sections were allowed to cool down for 5 minutes, blocked with Tris-goat immunoglobulin (Ig) for 15 minutes, and incubated for 60 minutes at room temperature with anti-PKCδ polyclonal rabbit antibody (A7034; Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:200 dilution. Detection was performed on a Ventana BenchMark using a Ventana iView DAB detection kit (AZ, 760-091). The other immunohistochemical (IHC) stains included CD20, CD3, CD5, BCL-6, Mum-1, CD21, MIB-1, κ, λ, IgM, IgD, IgG, IgA, TdT, and EBV-encoded RNA (EBER). These were performed as previously published.9 Images were taken using an Olympus Bx41 microscope, objective UPlanFI 10×/030 and 20×/0.50 ∞/0.17, with an adaptor U-TV0.5xC using a digital camera Q-imaging Micropublisher 5.0 RTV. The images were captured using “Q-Capture Version 3.1” and imported into Adobe Photoshop 7.0

Evaluation of cell proliferation

PBMCs, either freshly isolated or thawed from liquid nitrogen−stored samples, were incubated with CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit (1 μM; Invitrogen). After 5 minutes, 10 volumes of RPMI/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) were added, and the cells were centrifuged and washed twice more with RPMI/10% FBS. A total of 2 × 105 cells were seeded into 48-well plates, stimulated with CD3/CD28 (Dynabeads T-cell activator from Invitrogen), or phytohemagglutinin (1 μ/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) as indicated in the figures, and cultured for 3-4 days. Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled cells were stained with APC-CD25 (BD Biosciences) or IgG control for 30 minutes at 4°C (dark). Cells were washed with PBS twice, and 10 000 live cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson FACSCanto II). For B-cell proliferation, 1 × 105 CFSE-labeled B cells were stimulated with F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (10 μg/mL; Jackson Laboratory), IL-4 (50 ng/mL; Cell signaling), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL; Cell signaling) for 5-6 days, and 10 000 live cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytokine measurement

Human B cells were purified by negative selection with the StemSep Human B-cell Enrichment kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 1 × 105 B cells were stimulated with F(ab′)2 anti-IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 48 hours and cell-free supernatants were harvested. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 cytokines were measured simultaneously with Fluorokine MAP Human Base Kit A (R&D Systems) using the Luminex 200 System (Luminex Corporation).

Apoptosis measurement

A total of 0.5-1 × 105 EBV-transformed B cells or PBMCs were aliquoted in triplicate into 96-well plates and cultured with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA: 100 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) or APO-1-3/Protein A (1 μg/mL; ENZO Life Sciences). After 24 hours (for EBV B cells) or 48 hours (for PBMCs), cell loss was determined by measuring the loss of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential with 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6; Calbiochem, EMC Biosciences) staining. To summarize, cells were incubated with 40 nM DiOC6 for 15 minutes at 37°C, and live cells (DiOC6) were counted by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson FACSCanto II) with constant time acquisition. The percentage of live cells was calculated according to the following formula: (number of live cells with APO-1-3 or PMA treatment)/(number of live cells without treatment) × 100.10

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates (Tris-Cl 50mM, pH 7.4; NP-40 0.5%; 0.15 M NaCl; 2mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; protease inhibitor from Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared from PBMCs, EBV-transformed B cells, or activated B cells (F(ab′)2 anti-IgM, IL-4, and CD40 ligand treatment of 5 days). Cell lysates were resolved on 4% to 12% NuPAGE Bis–Tris gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred on a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with the use of anti-PKCδ (Cell signaling) or anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies.

Gene expression

Total RNA was isolated from PBMCs or EBV-transformed B-cell lines with the RNeasy plus mini Kit (QIAGEN). One microgram of total cellular RNA was reverse transcribed by use of the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio Lad). Gene expression was analyzed by real-time PCR using a StepOne Plus real time PCR (Applied Biosystems) and Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. All reactions were performed in triplicate for 40 cycles. GAPDH was used as the endogenous control, and gene expression of PRKCD was quantitatively measured relative to 2 different normal donors. The relative quantitation of PRKCD expression was calculated with the comparative Ct method. For each sample, the threshold cycle (Ct) was determined, and the relative fold expression was calculated as follows: ΔCt = Ct of PRKCD − Ct of GAPDH. ΔΔCt = ΔCt of the normal sample − ΔCt of the patient sample. The relative fold expression was calculated using the equation 2ΔΔCt.

Transduction using lentivirus

PRKCD coding sequence was cloned into pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen (Clontech). The packaging mix (Clontech) and the pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen control vector or pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen-PRKCD were cotransfected into Lenti-X-293 cells (4 × 106 cells) with X-fect transfection reagent (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After 48 hours’ incubation, supernatant was collected and concentrated with Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech). Concentrated virus was resuspended with RPMI media and transduced into the patient’s EBV B-cell line. To improve infection efficiency, Polybrene (8 μg/mL) was added into media followed by centrifugation at 1500g for 1 hour. After 24 hours, the media was changed to virus-free complete RPMI media, and the cells were incubated for an additional 72 hours.

siRNA transfection

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-universal negative control and siRNA-PRKCD were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. B cells (3−5 × 106 cells) and PBMCs (1 × 106 cells) were transfected with 300 nM siRNA by the use of Amaxa electrophoration according to manufacturer’s instructions. The next day, transfected cells were washed with fresh RPMI/10% FBS, stained with CellTrace CFSE, and stimulated as described above. Using the Lonza transfection kit, we found that transfection efficiency was 25% in the B cells and 70% in the T cells within the PBMCs as determined by the pmaxGFP.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the means ± SE, and statistical analyses were performed with unpaired Student t test. The differences were considered significant when P < .05. The n values represent the number of experiments from multiple preparations.

Results

Clinical and laboratory findings

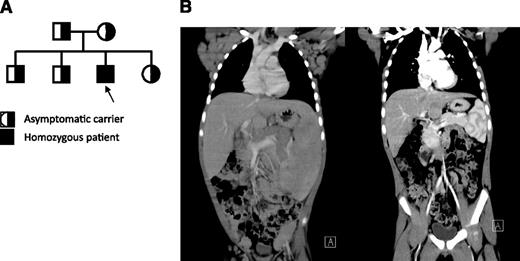

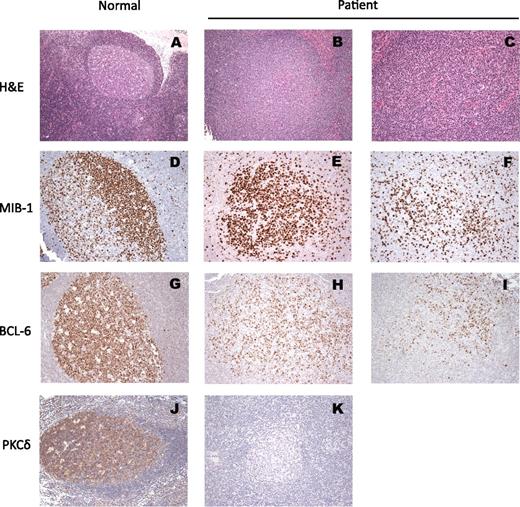

The patient is a Hispanic male born at term in 2005 to parents without known consanguinity; however, the families of both parents have been inhabitants of the same small town in northern Mexico for many generations (Figure 1A). His clinical history included recurrent otitis with bilateral perforated tympanic membranes and sinusitis that starting during in early childhood. He had persistent generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1B, left), accompanied by intermittent fevers starting at 3 years of age. Hepatosplenomegaly became very prominent by 5 years of age and marked mediastinal lymphadenopathy produced a superior vena cava syndrome manifested by markedly dilated chest veins. He had an intermittent facial rash in a butterfly distribution and confluent erythematous macules over the trunk and extremities but no other evidence for vasculitis or glomerulopathy. The patient had several autoantibodies at high titers, which are listed in Table 1. These autoantibodies (extractable nuclear antigens [ENAs]) had not lead to disease-specific manifestations other than a period of lupus-like rash. Shortly after this, he was started on immunomodulatory treatment.

Clinical, immunological, histopathological, and characterization of patient. (A) Pedigree of patient. Parents do not have any known consanguinity. All 3 unaffected children and both parents are heterozygous for the same point mutation in PRKCD, whereas the patient represents the only affected offspring who is homozygous for this change. (B) Coronal computed tomography scan images illustrate massive hepatosplenomegaly and mediastinal, axillary, inguinal lymphadenopathy before treatment (left) and after treatment (right).

Clinical, immunological, histopathological, and characterization of patient. (A) Pedigree of patient. Parents do not have any known consanguinity. All 3 unaffected children and both parents are heterozygous for the same point mutation in PRKCD, whereas the patient represents the only affected offspring who is homozygous for this change. (B) Coronal computed tomography scan images illustrate massive hepatosplenomegaly and mediastinal, axillary, inguinal lymphadenopathy before treatment (left) and after treatment (right).

Laboratory evaluation at 5 years revealed a slight leukocytosis, normochromic normocytic anemia, and borderline thrombocytopenia that were presumed to be secondary to splenic sequestration as there was no evidence for an autoimmune cytopenia. Significantly increased sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase elevation, and hypergammaglobulinemia also were noted at this time (Table 1). Flow cytometry revealed B-cell lymphocytosis (30% of lymphocytes) with the majority of B cells expressing CD5, whereas class switched B-cell memory subsets were diminished (Table 1).

The patient had previous evidence for seroconversion to EBV, although he had persistently detectable EBV copy numbers between 2000 and 8000 genomes/μL. NK cells were slightly decreased, but his NK-cell cytolytic activity was very diminished as compared with normal control patients (supplemental Figure 1; see the Blood Web site); NKT cells were present in normal numbers. Although the patient did not have a significant and persistent increase in α-β T-cell receptor double-negative T cells, molecular screening for ALPS and ALPS-like related genes (FAS, FASL, CASP8, CASP10, NRAS, or KRAS) was undertaken and revealed no mutations. In addition, no mutations were detected in the X-linked lymphoproliferative disease genes SH2D1A and XIAP.

In an attempt to reduce his lymphadenopathy, the patient was treated with corticosteroids and rapamycin, which led to a remarkable and rapid reduction in the size of his lymph nodes and resolution of hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1B, right), as well as the transaminitis and elevated inflammatory markers.

Histopathologic findings

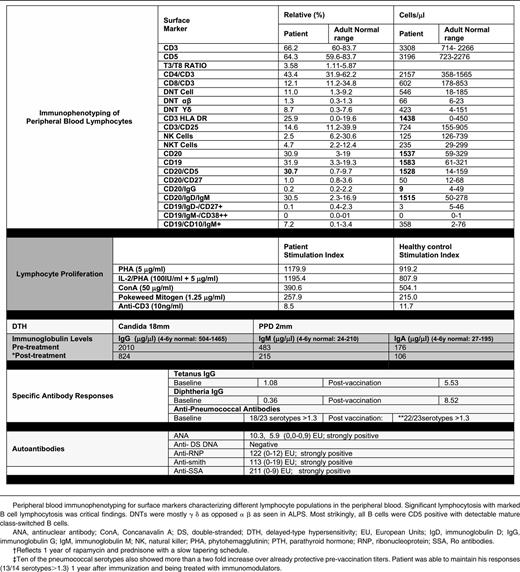

Microbiological evaluations of lymph node biopsies failed to identify an infectious etiology. The nodal architecture was preserved with open sinuses, expansion of the B-cell areas with prominent B follicles with ill-defined germinal centers lacking polarization (Figure 2). Mantles are indistinct on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining but are prominent by IgD staining (Figure 2; supplemental Figure 2). Residual reactive paracortex was noted, as well as monocytoid B-cell reaction. Typical histological features of ALPS were not observed. Gene rearrangement studies for T cells and B cells were negative for a clonal process. An increased number of CD5 cells with a biphasic pattern also was noted (not shown). Plasma cells in the lymph node were not increased, were polyclonal as determined by κ and λ light chain expression, and showed IgM>IgG>IgA (not shown). There was no evidence for significant EBV involvement as assessed by EBER staining.

Histopathology of the patient lymph node as compared with a reactive node from an otherwise-healthy node. (A) H&E stain reactive follicle with polarized germinal center and mantle; (D) IHC for MIB-1: the proliferating lymphoid cells within the germinal centers are positive with polarization (dark zone); (G) IHC for BCL-6 (the master regulator of the GC formation): the entire reactive germinal center is positive for BCL-6. (J) IHC stain for PKCδ showing diffusely positive cytoplasmic stain. All the remaining photos are from the lymph node biopsy from our patient: (B) and (C) H&E stains of follicles with varying degree of ill-defined germinal center lacking mantles. (E) and (F) IHC for MIB-1: variable degree of proliferation in different germinal centers is seen with lack of polarization. (H) and (I) IHC for BCL-6: a relative small number of positive cells are present within each germinal center in comparison with the reactive follicle. (K) Absence of PKCδ stain in patient’s lymph node, compared with (J).

Histopathology of the patient lymph node as compared with a reactive node from an otherwise-healthy node. (A) H&E stain reactive follicle with polarized germinal center and mantle; (D) IHC for MIB-1: the proliferating lymphoid cells within the germinal centers are positive with polarization (dark zone); (G) IHC for BCL-6 (the master regulator of the GC formation): the entire reactive germinal center is positive for BCL-6. (J) IHC stain for PKCδ showing diffusely positive cytoplasmic stain. All the remaining photos are from the lymph node biopsy from our patient: (B) and (C) H&E stains of follicles with varying degree of ill-defined germinal center lacking mantles. (E) and (F) IHC for MIB-1: variable degree of proliferation in different germinal centers is seen with lack of polarization. (H) and (I) IHC for BCL-6: a relative small number of positive cells are present within each germinal center in comparison with the reactive follicle. (K) Absence of PKCδ stain in patient’s lymph node, compared with (J).

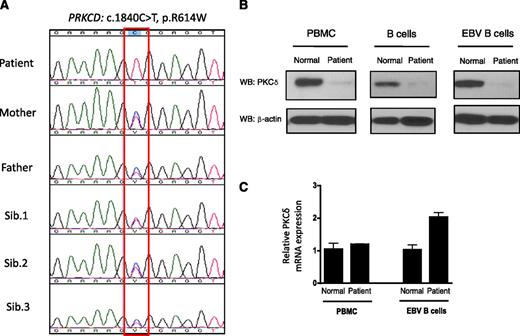

PRKCD mutation and gene expression

To identify the underlying genetic defect in the patient, we performed whole-exome sequencing and identified a deleterious PRKCD c.1840C>T, p.R614W homozygous mutation. This result was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 3A). Both parents and all 3 siblings are heterozygous carriers, and they are healthy without any clinical evidence or history of lymphoproliferation and/or autoimmunity (Figure 3A). The p.R614W mutation is located in the nuclear localization sequence, which has been shown to be important for the nuclear import of PKCδ, a process required for apoptosis.11 Western blot analysis revealed low levels of PKCδ protein expression in the patient’s PBMCs, B cells, and EBV-transformed B cells, although the mRNA expression level was comparable or greater than that of normal cells (Figure 3B-C). Western blots also demonstrated normal expression of the other PKC isoforms (PKCα, β, ε) in PBMCs and in EBV-transformed B cells (data not shown), indicating that PKCδ protein expression is specifically reduced in the patient. We also confirmed absence of PKCδ expression in the patient’s lymph node by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2K). We also tested PKCδ protein expression in heterozygous family members, and the PKCδ expression was similar to heath control (data not shown).

Identification of PKCδ mutation and protein expression. (A) Sequencing of PRKCD with genomic DNA from blood from the index patient, parents, and 3 siblings. (B) Immunoblot analysis of PKCδ and of the control protein β-actin in the cells from the patient and normal volunteer. Purified B cells were activated with F(ab′)2 specific for IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 5 days, and then cell lysates were subjected to western blot (WB) analysis. The protein lysates from PBMCs and EBV-transformed B cells were used without stimulation. (C) PRKCD gene expression levels in the PBMCs and EBV-transformed B cells are expressed as a relative expression of normal cells. Data are represented as means ± SE of n = 3 separate experiments.

Identification of PKCδ mutation and protein expression. (A) Sequencing of PRKCD with genomic DNA from blood from the index patient, parents, and 3 siblings. (B) Immunoblot analysis of PKCδ and of the control protein β-actin in the cells from the patient and normal volunteer. Purified B cells were activated with F(ab′)2 specific for IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 5 days, and then cell lysates were subjected to western blot (WB) analysis. The protein lysates from PBMCs and EBV-transformed B cells were used without stimulation. (C) PRKCD gene expression levels in the PBMCs and EBV-transformed B cells are expressed as a relative expression of normal cells. Data are represented as means ± SE of n = 3 separate experiments.

PKCδ deficiency induces increased B-cell proliferation

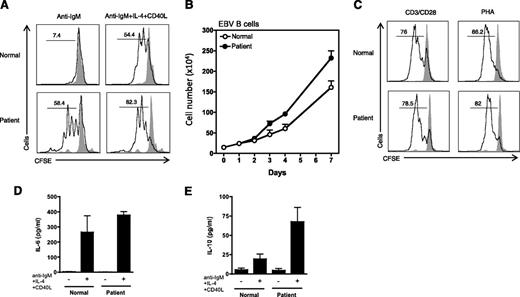

Recently, the generation of PKCδ−/− mice has revealed a striking functional role for this protein in B-cell proliferation and maintenance of tolerance.3 PKCδ−/− mice exhibit B-lineage−specific cell expansion with increased number of naïve and activated follicular mature B cells and an increased number of germinal centers within the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes.3 Interestingly, the patient’s phenotype, including enlarged spleen and lymph nodes, and an expanded peripheral B lymphocyte population involving predominantly naïve cells, was similar to those of PKCδ−/− mice. To test whether the patient’s B cells were hyperproliferative, we measured the proliferative potential of B cells from PBMCs by using CFSE staining. Stimulation of purified B cells with either F(ab′)2 anti-IgM alone or in combination with IL-4 and CD40 ligand revealed that the proliferative response of the patient’s B cells was significantly greater than that of B cells from a normal control (Figure 4A). EBV-transformed B cell lines from the patient also grew at a faster rate than control lines (Figure 4B). In contrast, T cells from the patient did not display an increased rate of proliferation compared with healthy controls (Figure 4C).

Cell proliferation and cytokine generation. (A) Enriched B cells were stained with CFSE (1 μM) and stimulated with F(ab′)2 specific for anti-IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 5 days. Percent cells having undergone at least one cellular division, (numbers above the lines), assessed by CFSE dilution. Gray solid peak is an unstimulated cell. (B) EBV-transformed B cells from 3 normal and 2 different batches of patient were counted for 7 days. (C) PBMCs were stained with CFSE (1 μM) and stimulated Dynabeads T-cell activator CD3/CD28 for 3 days. PHA, phytohemagglutinin. (D) and (E) Enriched B cells were stimulated as indicated. After 48 hours, cell-free supernatants were harvested and cytokines measured as described in the Cytokine measurement section in the Materials and methods. Data from panels A and C are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data from panels D and E were represented as means ± SE of n = 3 separate experiments.

Cell proliferation and cytokine generation. (A) Enriched B cells were stained with CFSE (1 μM) and stimulated with F(ab′)2 specific for anti-IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 5 days. Percent cells having undergone at least one cellular division, (numbers above the lines), assessed by CFSE dilution. Gray solid peak is an unstimulated cell. (B) EBV-transformed B cells from 3 normal and 2 different batches of patient were counted for 7 days. (C) PBMCs were stained with CFSE (1 μM) and stimulated Dynabeads T-cell activator CD3/CD28 for 3 days. PHA, phytohemagglutinin. (D) and (E) Enriched B cells were stimulated as indicated. After 48 hours, cell-free supernatants were harvested and cytokines measured as described in the Cytokine measurement section in the Materials and methods. Data from panels A and C are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data from panels D and E were represented as means ± SE of n = 3 separate experiments.

The hyperproliferative B-cell phenotype seen in the PKCδ−/− mice was suggested to be secondary to an augmented B-cell secretion of IL-6.3 Evaluation of IL-6 secretion by the patient’s B cells after activation did not show statistically significant differences from the controls (Figure 4D). However, there was a striking elevation in IL-10 secretion by the patient’s B cells compared with healthy controls (Figure 4E).

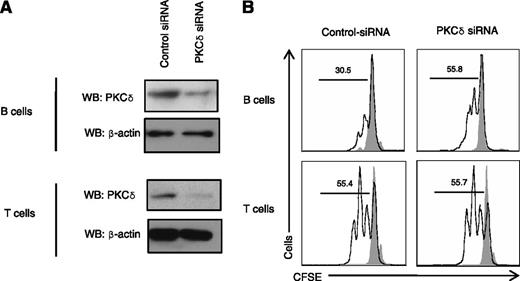

To demonstrate that the PKCδ deficiency was responsible for the B-cell hyperproliferative phenotype, we used siRNA to knock down PRKCD in B cells from healthy volunteers. Despite the low B-cell transfection efficiency (∼25%), an increase in B-cell proliferation was evident in siRNA-PKCδ transfected cells (Figure 5A-B). In contrast, the proliferative properties of siRNA-PKCδ primary T cells appeared normal (Figure 5B). Taken together, these experiments demonstrated that PKCδ deficiency in humans causes abnormal B-cell proliferation but does not appear to affect T cell proliferation.

Knockdown of PKCδ-induced B-cell proliferation. (A) B cells or PBMCs were transfected with siRNA-universal negative control or siRNA-PRKCD (300 nM) with Amaxa electrophoration according to the Materials and Methods. After 3 days, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to the western blots (WB). (B) B cells or PBMCs were transfected with siRNA-universal negative control or siRNA-PRKCD (300 nM). The next day cells were stained with CFSE (1 μM) and stimulated with F(ab′)2 specific for anti-IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 5 days (for B cells) or Dynabeads T cell activator CD3/CD28 for 3 days (for PBMCs). Percent cells having undergone at least one cellular division, (numbers above the lines), assessed by CFSE dilution. Gray solid peak is unstimulated cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Knockdown of PKCδ-induced B-cell proliferation. (A) B cells or PBMCs were transfected with siRNA-universal negative control or siRNA-PRKCD (300 nM) with Amaxa electrophoration according to the Materials and Methods. After 3 days, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to the western blots (WB). (B) B cells or PBMCs were transfected with siRNA-universal negative control or siRNA-PRKCD (300 nM). The next day cells were stained with CFSE (1 μM) and stimulated with F(ab′)2 specific for anti-IgM (10 μg/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), and CD40 ligand (10 μg/mL) for 5 days (for B cells) or Dynabeads T cell activator CD3/CD28 for 3 days (for PBMCs). Percent cells having undergone at least one cellular division, (numbers above the lines), assessed by CFSE dilution. Gray solid peak is unstimulated cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

PMA-induced apoptosis is defective in PKCδ deficiency

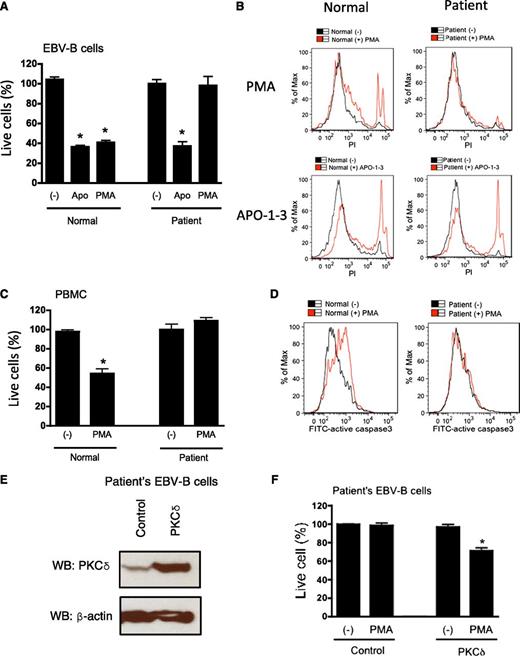

Phorbol esters, natural compounds that potently activate the classical and novel PKCs, trigger cell survival responses or apoptosis depending on the cell type and the relative expression of individual PKC isozymes.4,12 Numerous studies have shown that PKCδ is involved in proapoptic signaling upon phorbol ester stimulation and after DNA damage.13 Therefore, we tested PMA-induced cell death in the patient’s cells (EBV-transformed B cells and PBMCs). Although treatment with PMA induced 60% and 50% cell death in EBV-transformed B cells (Figure 6A-B) and PBMCs from normal control patients (Figure 6C), respectively, the patient’s cells were completely resistant to PMA-induced cell death. However, they demonstrated normal sensitivity to alternative inducers of apoptosis, including FAS and thapsigargin (Figure 6A-B and data not shown). It is well known that PKCδ is required for caspase-3 activation and induction of apoptosis after PMA overstimulation. To test whether deficiency of PKCδ expression interferes with caspase-3 activity and apoptosis, we measured capspase-3 activity with flow cytometry. As seen in Figure 6D, the patient’s EBV-transformed B cells failed to activate caspase-3 whereas the caspase-3 activity of the normal cells was increased by PMA. PBMCs also showed a similar defect in PMA-induced caspase-3 activation (data not shown).

Patients’ B cells were resistant to PMA-induced cell death. (A) and (C) EBV-transformed B cells or PBMCs were cultured with PMA (100 ng/mL) or APO-1-3/protein A (1 μg/mK each). After 24 hours (for EBV B cells) or 48 hours (for PBMCs), cells were stained with DiOC6 (40 nM) for 15 minutes and live cells were counted by flow cytometry by constant time acquisition. (B) EBV-transformed B cells were stimulated with or without PMA or APO-1-3 for 6 hours, stained with propidium iodide (PI; 50 ng/mL) for 15 minutes, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) EBV-transformed B cells were stimulated with or without PMA for 3 hours, and cells were stained with FITC-activated caspase-3 (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (E) and (F) The patient’s EBV-transformed were transduced with pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen control vector or pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen-RRKCD using lentivirus system. Overexpression of PKCδ was analyzed by western blots (WB; E). Cells were stimulated with PMA (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours, live cells were counted by flow cytometry by constant time acquisition (F). Analysis was performed by gating on live ZsGreen expressed cells. Data are represented as means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < .05 by Student t test for comparison with untreated cells.

Patients’ B cells were resistant to PMA-induced cell death. (A) and (C) EBV-transformed B cells or PBMCs were cultured with PMA (100 ng/mL) or APO-1-3/protein A (1 μg/mK each). After 24 hours (for EBV B cells) or 48 hours (for PBMCs), cells were stained with DiOC6 (40 nM) for 15 minutes and live cells were counted by flow cytometry by constant time acquisition. (B) EBV-transformed B cells were stimulated with or without PMA or APO-1-3 for 6 hours, stained with propidium iodide (PI; 50 ng/mL) for 15 minutes, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (D) EBV-transformed B cells were stimulated with or without PMA for 3 hours, and cells were stained with FITC-activated caspase-3 (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (E) and (F) The patient’s EBV-transformed were transduced with pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen control vector or pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen-RRKCD using lentivirus system. Overexpression of PKCδ was analyzed by western blots (WB; E). Cells were stimulated with PMA (100 ng/mL) for 24 hours, live cells were counted by flow cytometry by constant time acquisition (F). Analysis was performed by gating on live ZsGreen expressed cells. Data are represented as means ± SE of 3 separate experiments. *P < .05 by Student t test for comparison with untreated cells.

To demonstrate that the lack of PKCδ expression resulted in the defective PMA-induced cell death, we overexpressed wild-type PKCδ in the patient EBV B cells by the use of a lentiviral vector (Figure 6E). The overexpression of PKCδ in patient’s EBV-transformed B cells partially re-established the capacity of PMA to induce cell death (Figure 6F).

NK function studies

Although we are not aware of NK dysfunction in the PKCδ−/− mouse, given our patient’s chronic persistent EBV low-grade viremia, we explored this possibility. Using 51Cr-labeled K562 target cells, we found that the patient’s PBMCs exhibited markedly reduced NK activity, notably at greater effector/target ratios (supplemental Figure 2). In addition, in an enzyme-linked immunospot assay in which K562 target cells were used, we found that the patient’s PBMCs exhibited a reduced frequency of interferon-γ−producing cells: 0.03% (300 of 1 × 106 PBMCs) in the patient vs 0.12% to 0.35% in 2 control subjects (data not shown).

Discussion

We report here the first human disorder caused by PKCδ deficiency. Similar to the PKCδ−/− mouse, our patient presented with extensive lymphadenopathy and breakdown of B-cell tolerance, with autoantibody production and lupus-like skin disease.3 The impressive lymphocyte accumulation could be explained by the excessive proliferation of the patient’s B cells demonstrated ex vivo in the presence of substimuli such as anti-IgM treatment, which normally does not induce B-cell division. This finding translated histopathologically into lymph nodes with numerous follicles but lacking adequate germinal center and mantle separation, with fewer than normal BCL6-positive B cells. Peripheral blood immunophenotyping was also abnormal, with diminished memory B cells and increased numbers of CD5+ B cells. Interestingly, although in mice the B-cell hyperproliferative phenotype could be ascribed to an increased secretion of IL-6, we could not document the same in our patient. In contrast, we noticed a striking oversecretion of IL-10 by the patient’s cultured B cells. Because IL-10 is a B-cell trophic factor, this could explain in part the cellular phenotype. Interestingly, increased levels of IL-10 are a consistent finding in patients with ALPS, and this disorder is also associated with B-cell expansion, including increased CD5+ B cells, decreased memory B cells, and hypergammaglobulinemia.14,15 In addition, it is known that PKCδ itself is a negative regulator of the cell cycle.16-18 In addition to B-cell hyperproliferation, we also documented an apoptotic defect in B cells after PMA stimulation that was not observed using other stimuli of apoptosis.

The striking breakdown in B-cell tolerance seen in this patient highlights the key role of PKCδ in the maintenance of human B-cell homeostasis. This confirms findings in murine models that PKCδ is crucial for the adequate negative selection of B cells in the bone marrow.6,19 B-cell selection seems to be affected by DAG-independent Ca2+ signaling mediated by PKCδ, STIM1, and RasGRP, resulting in proapoptotic Erk signaling.19

The T-cell compartment appeared largely normal in the patient, with appropriate numbers of T-cell subsets and normal T-cell proliferation and activation in vitro. This finding is corroborated in vivo by the lack of clinical symptoms suggestive of cellular immunodeficiency. However, NK-cell function was severely impaired in our patient, as demonstrated by 3 separate assays, and serves as an explanation for the chronic, low-grade EBV infection observed in this individual. Further studies are necessary to understand how PKCδ deficiency affects NK-cell function.

The patient had an excellent clinical response to immunosuppressive treatment when we used a combination of rapamycin with steroids that resulted in rapid reversal of the lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. It is noteworthy that rapamycin has proven to be an effective therapeutic agent in controlling lymphoproliferation in patients with ALPS.20 Taken together, our studies define a novel immunodeficiency presenting with lymphoproliferative disorder and NK dysfunction, and establish PKCδ as a key player in the maintenance of B-cell tolerance.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for their contributions to the study and Dr Steven M. Holland for his support of our research activity.

Supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Intramural Research Program National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, and in part by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (contract HHSN261200800001E). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Authorship

Contribution: H.S.K. performed research, identified the cellular functional defect, coordinated the study, created the figures, and prepared the manuscript; J.E.N. performed genomic DNA sequencing analysis; A.R.-S. performed Sanger sequencing; M.Z. performed whole-exome next-generation sequencing; S.P. and M.O.E. performed pathology evaluation, special stains, and immunohistophathology; J.L.S. performed bioinformatics analysis and candidate gene discovery; A.A.H. coordinated the clinical protocol and sample collection; C.L.P. referred patient and provided clinical data and samples; D.A.L.P. and D.B.K. performed NK function assay and prepared EBV-transformed B-cell lines; T.A.F. supervised research and prepared the manuscript; and G.U. and J.B.O. planned and implemented the study and supervised the clinical and experimental work, data analyses, and manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: João Bosco Oliveira, Instituto de Medicina Integral-IMIP, Recife, PE Brazil; e-mail: bosco.oliveira@imip.org.br; and Gulbu Uzel, CRC B3-4141, MSC 1684, Bethesda, MD 20892-1684; e-mail: guzel@mail.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal