Key Points

Expressing dominant-negative RAG1 to inhibit BCR editing of autoreactivity in CLL-prone Eμ-TCL1 mice accelerates disease onset.

Gene expression profiling studies provide evidence of distinct but convergent pathways for CLL development.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a prevalent B-cell neoplasia that is often preceded by a more benign monoclonal CD5+ B-cell lymphocytosis. We previously generated transgenic mice expressing catalytically inactive RAG1 (dominant-negative recombination activating gene 1 [dnRAG1] mice) that develop an early-onset indolent CD5+ B-cell lymphocytosis attributed to a defect in secondary V(D)J rearrangements initiated to edit autoreactive B-cell receptor (BCR) specificity. Hypothesizing that CD5+ B cells in these animals represent potential CLL precursors, we crossed dnRAG1 mice with CLL-prone Eμ-TCL1 mice to determine whether dnRAG1 expression in Eμ-TCL1 mice accelerates CLL onset. Consistent with this hypothesis, CD5+ B-cell expansion and CLL progression occurred more rapidly in double-transgenic mice compared with Eμ-TCL1 mice. Nevertheless, CD5+ B cells in the 2 mouse strains exhibited close similarities in phenotype, immunoglobulin gene usage, and mutation status, and expression of genes associated with immune tolerance and BCR signaling. Gene expression profiling further revealed a potential role for prolactin signaling in regulating BCR editing. These results suggest a model in which benign accumulation of CD5+ B cells can be initiated through a failure to successfully edit autoreactive BCR specificity and may, in turn, progress to CLL upon introduction of additional genetic mutations.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most prevalent type of adult leukemia, affecting mainly the elderly. CLL is clinically indicated by an abundance of small lymphocytes in the bone marrow and peripheral blood (>5000/µL) which typically display a CD19+CD5+CD23+ and surface IgMlo immunophenotype.1 CLL is a heterogeneous disease that exhibits a variable clinical course.2 Immunoglobulin (Ig) gene mutation status and relative expression of CD38 and ZAP-70 are used as prognostic indicators for this disease: cases in which leukemic cells harbor unmutated Ig genes and/or express CD38 and ZAP-70 typically have the worst clinical prognosis.3 Emerging evidence suggests CLL likely evolves from a more benign and biologically similar condition called monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), which is clinically indicated by elevated numbers of CLL-like cells in peripheral blood (<5000 cells/µL) in the absence of cytopenias, lymphadenopathy, or organomegaly.4 MBL progresses to CLL at an estimated rate of 1% to 2% per year.4

CLL exhibits a restricted Ig gene repertoire and displays an antibody reactivity profile skewed toward cytoskeletal and membrane-associated self-, modified self-, and bacterial antigens.5 This reactivity profile is also shared by innate-like B1 and marginal zone (MZ) B cells that are positively selected for these specificities, as well as subsets of developing (transitional) and extrafollicular B cells that exhibit self-reactivity produced by primary Ig gene rearrangements or as an unintended consequence of somatic mutation, respectively.5 In response to self-reactivity, B cells may undergo secondary Ig gene rearrangements to “edit” or “revise” B-cell receptor (BCR) specificity to avoid autoreactivity.6,7 CD5 is normally expressed on subsets of normal B1 and human MZ B cells.5 In addition, CD5 expression may be induced on B cells undergoing receptor editing/revision,7,8 or rendered anergic by chronic (auto)antigenic stimulation,9 where it may function to negatively regulate BCR signaling and suppress B-cell activation to limit autoantibody production.10

In principle, B cells undergoing receptor editing/revision may be blocked from completing this process if a dominant-negative form of the recombination activating gene 1 (dnRAG1) protein (a component of the V(D)J recombination machinery that initiates antigen receptor gene rearrangement)11 is expressed in sufficient excess over endogenous RAG1. We recently generated dnRAG1 mice expressing a catalytically inactive, but DNA-binding competent, form of RAG1 in the periphery which show evidence of impaired secondary V(D)J recombination that occurs in response to self-reactivity.12 Interestingly, these animals develop a progressive, antigen-dependent, accumulation of CD5+ B cells which are clonally diverse, yet repertoire restricted, and possess a splenic B1-like immunophenotype.13 However, dnRAG1 mice do not develop CD5+ B-cell neoplasia.12 The indolent accumulation of CD5+ B cells in dnRAG1 mice is reminiscent of MBL, but the lack of progression to CLL in this model suggests additional factors are required to promote transformation. We considered T-cell leukemia 1 (TCL1) as a plausible factor because it is often overexpressed in CLL,14 and TCL1-transgenic (Eμ-TCL1) mice develop a CLL-like disease.15 The CLL cells emerging in Eμ-TCL1 mice phenotypically resemble those accumulating in dnRAG1 mice, but arise with delayed kinetics compared with dnRAG1 mice.12,15 We hypothesized that if molecular defects which promote benign CD5+ B-cell accumulation, such as impaired receptor editing, are a rate-limiting step in CLL progression, then dnRAG1 expression in Eµ-TCL1 mice should accelerate CD5+ B-cell accumulation and CLL onset compared with Eµ-TCL1 mice. Consistent with this possibility, we find that dnRAG1/Eµ-TCL1 double-transgenic (DTG) mice uniformly develop a progressive CD5+ CLL-like disease similar to that observed in Eμ-TCL1 mice, but with an earlier onset. CLL cells isolated from DTG mice are readily engrafted into SCID mice and cause a CLL-like disease with a stable donor phenotype. Gene expression profiling of normal B cells and transgenic CD5+ B cells demonstrated upregulation of several genes involved in immune suppression in transgenic CD5+ B cells, and implicated prolactin signaling through Prl2a1 as a potential mechanism for CD5+ B-cell accumulation in dnRAG1 and DTG mice. Some genes associated with poor prognosis in human CLL were shown to be differentially expressed in ill DTG mice relative to dnRAG1 and Eµ-TCL1 mice. Taken together, these data suggest a model in which defects in receptor editing/revision can promote emergence of MBL, which, in turn, can progress to CLL upon introduction of subsequent genetic lesions.

Methods

Mice

Eµ-TCL1 mice were kindly provided by C. M. Croce and Y. Pekarsky (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH).15 Eµ-TCL1 and dnRAG1 mice,12 both on C57Bl/6 backgrounds, were crossed to generate cohorts of wild-type (WT), dnRAG1, Eµ-TCL1, and DTG mice as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website). SCID mice (B6.CB17-prkdcscid/SzJ) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). This study was conducted under protocol 0866 approved by the Creighton University Institutional Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions prepared from spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood were depleted of red blood cells by hypotonic lysis, stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis or FACS as described in supplemental Methods.

Adoptive transfer

CD19+CD5+ B cells were sorted from spleens of 36-week-old DTG mice and 1 × 106 cells injected into the tail veins of 7- to 9-week-old SCID mice. Blood was collected from tail veins every 6 weeks and analyzed by flow cytometry until the experimental endpoint was reached 3 months after adoptive transfer.

Histopathology

Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Blood was collected at experimental endpoint and smears immediately prepared and stained with Wright-Giemsa.

Ig gene analysis

For clonality analysis, genomic DNA isolated from spleen tissue was analyzed by Southern hybridization using a 32P-labeled JH probe as described in supplemental Methods. To analyze Ig gene rearrangements, splenic DNA was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primer sets for IgH (VHJ558 sense and 3′ JH4 antisense), Igκ (Vκ sense and 3′ Jκ5 antisense), and CD14 (as an input control) as described previously.12 To analyze Ig gene usage and mutational status, IgH and Igκ genes were amplified from complementary DNA (cDNA) prepared from spleen tissue obtained from 3 ill Eμ-TCL1 and 3 ill DTG mice, and the amplicons were cloned, sequenced, and compared with germline Ig sequences as described in supplemental Methods.

Ig levels

Serum Igs were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with IMMUNO-TEK mouse IgM and IgG kits (ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density was measured with VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Microarray

Affymetrix GeneChip hybridizations were performed using biotin end-labeled cDNA prepared from splenic CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells isolated from WT mice and splenic CD19+CD5+ B cells isolated from transgenic mice as described in supplemental Methods. Array data sets were normalized using the Robust Multichip Average algorithm included in the Affymetrix Expression Console software. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analyses (PCA) were performed using dChip16 with the parameters described in the figure legends. Some array data sets were also compared with publically accessible microarray data sets derived from developing, mature, and activated B-cell subsets17 as described in supplemental Methods. Microarray data sets have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus under GEO Series accession number GSE44940.

Real-time quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from frozen spleen tissue using the Ambion Ribopure Kit according to manufacturer instructions. cDNA was prepared from DNAse I-treated RNA using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and subjected to PCR using primer sets for Prl2a1, Il10, Sox4, Rgs13, Sell, and β-actin (primer sequences available in supplemental Methods) with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on an ABI 7500 Fast instrument (Applied Biosystems) as described.12 Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method using β-actin as the calibrator.

Statistics

Statistics were performed using PASW software version 19 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Differences between groups were determined by 1-way analysis of variance. A P value ≤ .05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Results

dnRAG1 expression accelerates leukemogenesis in Eμ-TCL1 mice

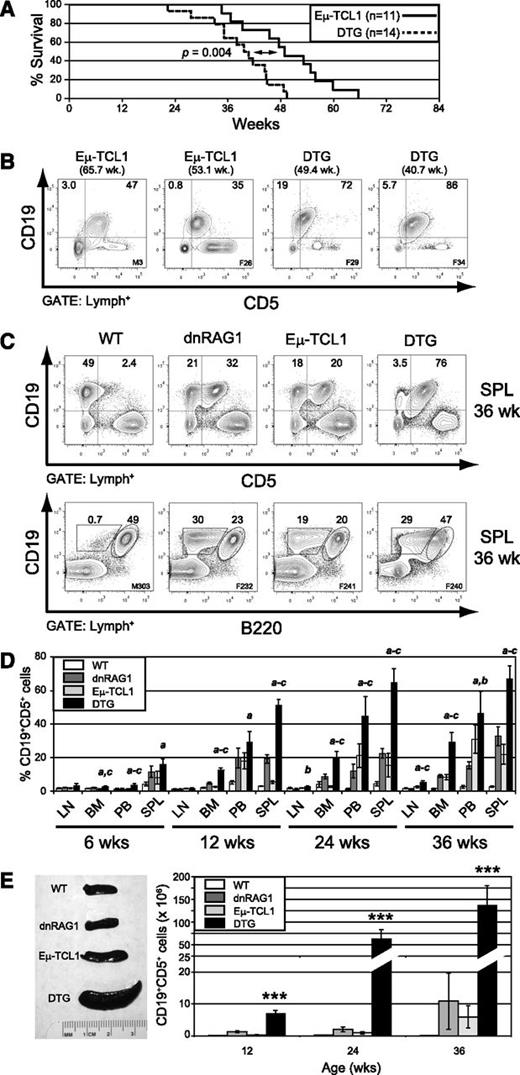

To test the hypothesis that dnRAG1 transgene expression accelerates disease progression in Eμ-TCL1 mice, we crossed Eμ-TCL1 and dnRAG1 transgenic mice and performed survival analysis on a cohort of Eμ-TCL1 (n = 11) and DTG (n = 14) mice. Consistent with our hypothesis, DTG mice showed a significantly shorter lifespan compared with Eμ-TCL1 mice (P = .004), with median survival times of 39.6 and 49 weeks, respectively (Figure 1A). At end point, all DTG mice were visibly ill, showing labored breathing and evidence of splenomegaly that necessitated euthanasia. Splenomegaly was confirmed on necropsy and a mixed population of small and large lymphocytes was evident in peripheral blood smears (supplemental Figure 1A). All ill Eµ-TCL1 and DTG mice showed an abundance of CLL-like CD19+CD5+ B cells in the spleen (Figure 1B) that displayed an IgM+B220+CD11blo/− phenotype, although the relative expression of these antigens varied slightly between individuals (supplemental Figure 1B).

dnRAG1 expression in Eμ-TCL1 mice shortens lifespan and accelerates CD5+ B-cell accumulation. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Eμ-TCL1 (n = 11) and DTG (n = 14) mice. Statistical analysis between groups was performed using the log-rank test (median survival: 39.6 and 49.0 weeks for DTG and Eμ-TCL1 mice; P = .004). (B) The percentage of splenic CD19+CD5+ B cells among gated lymphocytes is shown at end point for 2 representative Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic lymphocytes from 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice showing the expression of CD19 and either CD5 (top row) or B220 (bottom row). The percentage of CD19+CD5+, CD19+CD5−, CD19+B220hi, CD19+B220lo cells is shown for representative animals. (D) The percentage of CD19+CD5+ cells in lymph node (LN), bone marrow (BM), peripheral blood (PB), and spleen (SPL) of 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice (n = 5-6 animals per genotype per time point) was determined using flow cytometry as in panel A and presented in bar graph format. Error bars represent the SEM. Statistically significant differences (P < .05) between values obtained for DTG mice relative to WT (a), dnRAG1 (b), or Eμ-TCL1 (c) mice are indicated. (E) Spleen cellularities were measured at 12, 24, and 36 weeks of age for WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG to determine the frequency of splenic CD19+CD5+ cells. Spleens from representative animals of each genotype are shown at left, and the frequency of CD19+CD5+ cells for each genotype and time point are presented in bar graph format at right. Error bars represent the SEM. ***Values obtained for DTG mice are significantly different (P < .001) from those obtained for WT, dnRAG1, or Eμ-TCL1 mice.

dnRAG1 expression in Eμ-TCL1 mice shortens lifespan and accelerates CD5+ B-cell accumulation. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of Eμ-TCL1 (n = 11) and DTG (n = 14) mice. Statistical analysis between groups was performed using the log-rank test (median survival: 39.6 and 49.0 weeks for DTG and Eμ-TCL1 mice; P = .004). (B) The percentage of splenic CD19+CD5+ B cells among gated lymphocytes is shown at end point for 2 representative Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic lymphocytes from 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice showing the expression of CD19 and either CD5 (top row) or B220 (bottom row). The percentage of CD19+CD5+, CD19+CD5−, CD19+B220hi, CD19+B220lo cells is shown for representative animals. (D) The percentage of CD19+CD5+ cells in lymph node (LN), bone marrow (BM), peripheral blood (PB), and spleen (SPL) of 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice (n = 5-6 animals per genotype per time point) was determined using flow cytometry as in panel A and presented in bar graph format. Error bars represent the SEM. Statistically significant differences (P < .05) between values obtained for DTG mice relative to WT (a), dnRAG1 (b), or Eμ-TCL1 (c) mice are indicated. (E) Spleen cellularities were measured at 12, 24, and 36 weeks of age for WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG to determine the frequency of splenic CD19+CD5+ cells. Spleens from representative animals of each genotype are shown at left, and the frequency of CD19+CD5+ cells for each genotype and time point are presented in bar graph format at right. Error bars represent the SEM. ***Values obtained for DTG mice are significantly different (P < .001) from those obtained for WT, dnRAG1, or Eμ-TCL1 mice.

Time-course study of CLL-like disease progression in DTG mice

Given the results of the survival analysis, we next analyzed WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice at 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks of age to more carefully compare CD5+ B-cell accumulation rates using flow cytometry. The last time point was chosen because it was close to the median survival of DTG mice. At 36 weeks, CD19+CD5+ (or alternatively CD19+B220lo) B cells represented a small fraction of total splenic B cells in WT mice, but were abundant in dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice (Figure 1C). Further analysis of the CD19+B220lo population from dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice showed uniform CD5+CD21−CD23− staining and similar surface IgM levels (supplemental Figure 2A); surface IgD levels were comparable between dnRAG1 and DTG mice, but slightly higher than in Eμ-TCL1 mice (supplemental Figure 2A).

As expected, CD5+ B cells accumulated more rapidly in DTG mice compared with either dnRAG1 or Eμ-TCL1 mice in all tissues tested (Figure 1D). However, the frequency of CD5+ B cells differed substantially between the various sites. For example, at 36 weeks of age, CD5+ B cells comprised on average 5% of lymphocytes in lymph nodes of DTG mice, compared with 1.1%, 2.4%, and 1.5% for dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and WT mice, respectively. In spleen, by contrast, CD5+ B cells represented on average 67% of lymphocytes in DTG mice, compared with 33%, 22%, and 2.7% for dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and WT mice, respectively. (Figure 1D). By 36 weeks, all DTG mice exhibited splenomegaly, with average sizes ranging from threefold to fourfold higher than dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice, to over 10-fold greater than WT mice (Figure 1E left panel; supplemental Figure 2B). At all time points tested, DTG mice showed a higher absolute number of splenic CD5+ B cells compared with the other genotypes (Figure 1E right panel). Along with CD5+ B-cell expansion, 36-week-old DTG mice also showed higher absolute numbers of splenic CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD25+ T cells compared with the other genotypes (supplemental Figure 2D). By contrast, there were no significant differences between the transgenic animals in the number of these cells found in the lymph nodes.

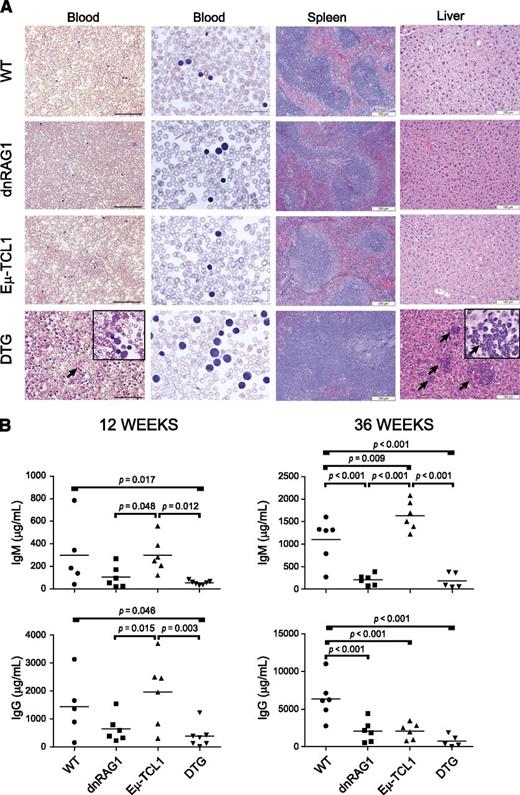

All 36-week-old DTG mice showed evidence of lymphocytosis by histopathological evaluation of blood smears and white blood cells counts (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure 2C); smudge cells similar to those observed in CLL patients were also frequently detected (Figure 2A). In the spleen, extensive lymphocytic infiltrates were observed in DTG mice, with a corresponding loss of splenic architecture (Figure 2A). Abnormal lymphocytic infiltrates were clearly apparent in the livers of all 36-week-old DTG mice, but not in bone marrow or kidneys (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure 3).

DTG mice show evidence of CLL-like disease and hypogammaglobulinemia at 36 weeks. (A) Blood smears were developed with Wright-Giemsa stain. Images (×200 and ×600) were acquired using Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and Optronics camera running MagnaFire software (Optronics, Goleta, CA). Paraffin-embedded spleen and kidney sections were developed with hematoxylin and eosin. Images (×100 for spleen and ×200 for liver) were acquired using a Nikon i80 microscope and DigiFire camera running ImageSys digital imaging software (Soft Imaging Systems GmBH, Munster, Germany). DTG mice at this age show peripheral blood lymphocytosis with frequent occurrence of smudge cells (arrow, see inset), loss of splenic architecture, and infiltration of leukemic cells in liver (arrows). Scale bars: blood and liver, 100μM; spleen, 200μM. (B) Serum IgM and IgG levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for groups of 12- and 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice. Individual values and means (indicated by horizontal bar) are shown for each group; statistically significant differences between groups are indicated.

DTG mice show evidence of CLL-like disease and hypogammaglobulinemia at 36 weeks. (A) Blood smears were developed with Wright-Giemsa stain. Images (×200 and ×600) were acquired using Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and Optronics camera running MagnaFire software (Optronics, Goleta, CA). Paraffin-embedded spleen and kidney sections were developed with hematoxylin and eosin. Images (×100 for spleen and ×200 for liver) were acquired using a Nikon i80 microscope and DigiFire camera running ImageSys digital imaging software (Soft Imaging Systems GmBH, Munster, Germany). DTG mice at this age show peripheral blood lymphocytosis with frequent occurrence of smudge cells (arrow, see inset), loss of splenic architecture, and infiltration of leukemic cells in liver (arrows). Scale bars: blood and liver, 100μM; spleen, 200μM. (B) Serum IgM and IgG levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for groups of 12- and 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice. Individual values and means (indicated by horizontal bar) are shown for each group; statistically significant differences between groups are indicated.

Human CLL patients typically develop progressive hypogammaglobulinemia.18,19 Previously, we showed that dnRAG1 mice exhibit defective natural IgM and IgG antibody production correlated with an intrinsic B-cell hyporesponsiveness toward antigenic stimulation.12 To determine whether Eμ-TCL1 expression modulates antibody production in dnRAG1 mice, we compared serum IgM and IgG levels in WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice at 12 and 36 weeks (Figure 2B). Consistent with earlier results,12 dnRAG1 mice showed twofold to threefold lower IgM and IgG levels compared with WT mice at 12 weeks; at 36 weeks, this reduction was even more pronounced (fourfold to eightfold). By contrast, IgM and IgG levels in Eμ-TCL1 and WT mice were similar at 12 weeks, but at 36 weeks, Eμ-TCL1 mice showed elevated IgM levels and decreased IgG levels compared with WT mice. Interestingly, antibody levels in DTG mice resembled dnRAG1 mice, but showed slightly lower serum IgM and IgG levels at both time points. Thus, these data suggest that suppressed antibody production in dnRAG1 mice expression is not overcome by concomitant Eμ-TCL1 expression.

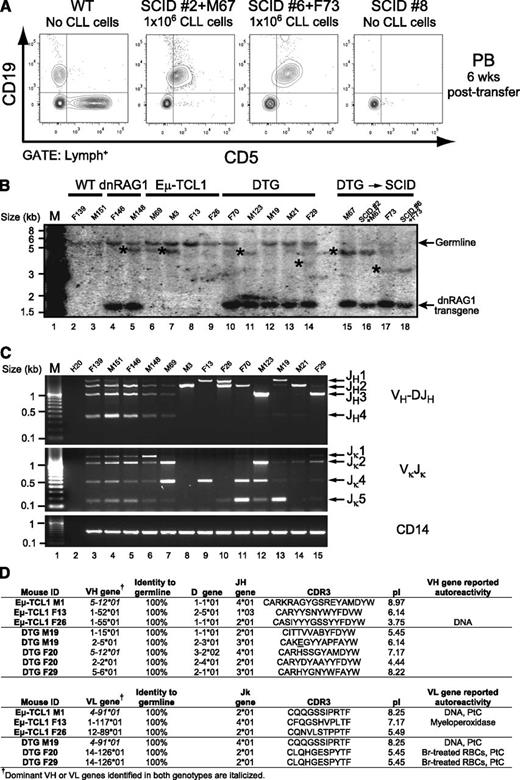

Evidence for clonal transformation of CD5+ B cells in DTG mice

The CLL-like B cells emerging in Eμ-TCL1 mice are known to be leukemogenic.20 To test whether CLL-like cells in DTG mice are also leukemogenic, 106 splenic CD19+CD5+ B cells from 2 different 36-week-old DTG mice were injected intravenously into SCID recipient mice. In both cases, successful engraftment was indicated by flow cytometry 6 weeks after adoptive transfer (Figure 3A). By 3 months, all SCID mice receiving CD5+ B cells from DTG mice developed splenomegaly (supplemental Figure 4A), peripheral blood lymphocytosis (supplemental Figure 4B), and infiltration of spleen, bone marrow, and lymph nodes by leukemic cells (supplemental Figure 4C).

CD19+CD5+ B cells from DTG mice are leukemogenic. (A) CD19+CD5+ splenocytes (106 cells) were purified by FACS from 2 different DTG mice and injected into the tail vein of recipient SCID mice. Mice were bled every 6 weeks, and analyzed for the appearance of CD19+CD5+ cells using flow cytometry. Normal C57Bl/6 mice and sham-injected SCID mice were included as controls. CD19+CD5+ B cells were readily detected in SCID recipients but not control animals at 6 weeks posttransfer. (B) Genomic DNA prepared from spleens of 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice (lanes 2-14), as well as DTG donor and SCID recipient mice in panel A (lanes 15-18), was subjected to Southern hybridization using a JH-probe. *Nongermline bands. The JH probe contains a portion of the Eμ enhancer, and therefore also detects the dnRAG1 transgene which contains this element.12 (C) VH-to-DJH and Vκ-to-Jκ rearrangements were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA samples described in panel B. Rearrangements to a given J segment are shown at right. The non-rearranging CD14 locus was amplified from the diluted genomic DNA templates as a loading control. (D) The most represented IgVH and IgVκ gene sequences from three ill Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice were analyzed to identify gene usage, mutation status, CDR3 composition and pI, and reported reactivity profile (summarized from supplemental Tables 1-2).

CD19+CD5+ B cells from DTG mice are leukemogenic. (A) CD19+CD5+ splenocytes (106 cells) were purified by FACS from 2 different DTG mice and injected into the tail vein of recipient SCID mice. Mice were bled every 6 weeks, and analyzed for the appearance of CD19+CD5+ cells using flow cytometry. Normal C57Bl/6 mice and sham-injected SCID mice were included as controls. CD19+CD5+ B cells were readily detected in SCID recipients but not control animals at 6 weeks posttransfer. (B) Genomic DNA prepared from spleens of 36-week-old WT, dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice (lanes 2-14), as well as DTG donor and SCID recipient mice in panel A (lanes 15-18), was subjected to Southern hybridization using a JH-probe. *Nongermline bands. The JH probe contains a portion of the Eμ enhancer, and therefore also detects the dnRAG1 transgene which contains this element.12 (C) VH-to-DJH and Vκ-to-Jκ rearrangements were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA samples described in panel B. Rearrangements to a given J segment are shown at right. The non-rearranging CD14 locus was amplified from the diluted genomic DNA templates as a loading control. (D) The most represented IgVH and IgVκ gene sequences from three ill Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice were analyzed to identify gene usage, mutation status, CDR3 composition and pI, and reported reactivity profile (summarized from supplemental Tables 1-2).

We previously showed that the CD5+ B cells accumulating in dnRAG1 mice are clonally diverse, but repertoire restricted.12 To determine whether CD5+ B cells in DTG mice are also clonally diverse, or have instead undergone oligoclonal or monoclonal expansion indicative of transformation, we analyzed genomic DNA prepared from spleens of 36-week-old WT and transgenic mice by Southern hybridization to detect clonal rearrangements in the IgH locus (Figure 3B). This analysis was also performed on DTG donor animals and SCID recipient mice at experimental end point (3 months). We found that about half of the dnRAG1 (1 of 2), Eμ-TCL1 (2 of 4), and DTG (4 of 7) mice analyzed showed the presence of nongermline bands, indicative of clonal expansion (Figure 3B lanes 2-14). Notably, the pattern of nongermline bands observed in samples prepared from donor DTG mice and the corresponding SCID recipient mice were identical (Figure 3B compare lanes 15-18), suggesting the leukemic cells are stable and do not undergo further IgH gene rearrangement after adoptive transfer.

Because some Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice did not show obvious evidence of clonal outgrowth by Southern blotting, we used PCR to compare the pattern of IgH and Igκ gene rearrangements between the 4 genotypes of animals analyzed in Figure 3B. As expected from our earlier studies,12 WT and dnRAG1 mice showed a clonally diverse B-cell repertoire that includes rearrangements to all 4 functional JH and Jκ gene segments, but dnRAG1 mice showed a bias toward Jκ1 and Jκ2 gene usage consistent with a defect in secondary V(D)J recombination (Figure 3C compare lanes 3-6). By contrast, all Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice showed a highly restricted pattern of V(D)J rearrangements (Figure 3C compare lanes 3-6 to 7-15). Taken together, these data suggest that CD5+ B cells accumulating in DTG mice represent a clonal expansion of leukemic B cells.

Previous studies have shown that leukemic cells in Eμ-TCL1 mice harbor largely unmutated Ig genes that encode CDR3 sequences enriched in serine, tyrosine, and charged residues, features which are also observed in aggressive CLL in humans.20 To determine whether leukemic cells from DTG mice share these characteristics, we analyzed IgH and Igκ sequences from 3 ill Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice (Figure 3D and supplemental Tables 1-2). We found that, like Eμ-TCL1 mice, Ig gene sequences in DTG mice are mostly unmutated and encode CDR3 regions enriched in serine, tyrosine, and charged residues. Indeed, some of the same genes and CDR3 sequences are recovered from both genotypes. For example, sequences utilizing the VH segments 1-55, 5-6, and 5-12 and/or containing the VH CDR3 sequence encoding “YYGSS” were amplified from both Eμ-TCL1 and DTG animals. We also detected recurrent Vκ4-91 and Vκ14-126 usage in Eμ-TCL1 and DTG mice. Several of these VH and Vκ sequences were also represented among those amplified from Eμ-TCL1 mice by Yan et al.21 Many of these gene sequences are associated with reactivity toward autoantigens such as DNA, cardiolipin, and phosphatidyl choline (Figure 3D and supplemental Tables 1-2).

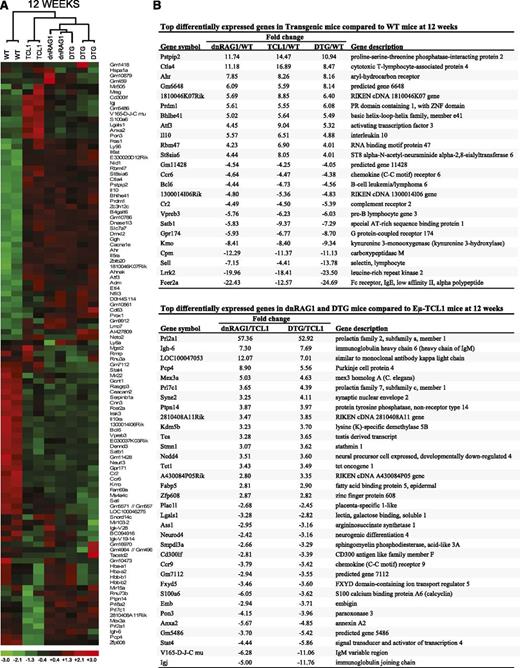

Gene expression profiling reveals distinct gene expression patterns in CD5+ B cells from young and old transgenic mice

To gain insight into the relative contribution of the individual dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 transgenes in promoting CLL-like disease in DTG mice, and identify genes that are differentially expressed between the animals as function of age and disease progression, we compared the gene expression profiles of splenic CD19+CD5+ B cells from 12-week-old dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice and splenic CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells from 2 age-matched WT mice, and repeated this analysis using ill DTG mice and their age-matched counterparts.

Initially, we performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis to determine how closely the sorted B-cell populations from WT and transgenic mice resemble one another at each time point (Figures 4A and 5A). Perhaps not surprisingly, at both time points the clustering analysis showed that the transgenic CD5+ B-cell gene expression profiles were more similar to each other than to the WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B-cell profiles. These experiments also revealed that at 12 weeks of age, CD5+ B cells from DTG mice resembled those from dnRAG1 mice more closely than Eμ-TCL1 mice (Figure 4A). Indeed, only 2 genes (Neto2 and Lmo7) were differentially expressed by more than threefold between dnRAG1 and DTG mice at this time point (supplemental Table 3). In older animals, the gene expression profiles obtained from DTG mice showed less similarity to those from dnRAG1 mice than at 12 weeks, and instead clustered more closely with the Eμ-TCL1 profile (Figure 5A). Additional comparison with gene expression profiles available for normal B1 cells and splenic developing, mature, and activated B-cell subsets using hierarchical clustering and PCA showed that the CD5+ B-cell gene expression profiles from the transgenic mice studied here most closely resembled the signature for normal splenic B1a cells by both analyses, but also shared some features of MZ B cells by PCA (supplemental Figure 5).

Identification of genes differentially expressed in WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells and CD19+CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice at 12 weeks. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of a set of 107 genes that meet the filtering criterion which set the SD for logged data between 0.85 and 1000, and the expression level at >5 in 25% of the samples. (B) A list of common genes among the 50 genes that display the greatest differential expression in WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells relative to CD19+CD5+ B cells from all transgenic mice is shown in the top panel. For this analysis, pairwise comparisons were performed using the lower 90% confidence bound interval for genes with ±1.2-fold change filtering criterion. Genes with a mean expression value of <50 in a comparison pair were not included. A list of common genes among the 50 genes that display the greatest differential expression in CD19+CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice is also shown in the bottom panel.

Identification of genes differentially expressed in WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells and CD19+CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1, Eμ-TCL1, and DTG mice at 12 weeks. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of a set of 107 genes that meet the filtering criterion which set the SD for logged data between 0.85 and 1000, and the expression level at >5 in 25% of the samples. (B) A list of common genes among the 50 genes that display the greatest differential expression in WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells relative to CD19+CD5+ B cells from all transgenic mice is shown in the top panel. For this analysis, pairwise comparisons were performed using the lower 90% confidence bound interval for genes with ±1.2-fold change filtering criterion. Genes with a mean expression value of <50 in a comparison pair were not included. A list of common genes among the 50 genes that display the greatest differential expression in CD19+CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice is also shown in the bottom panel.

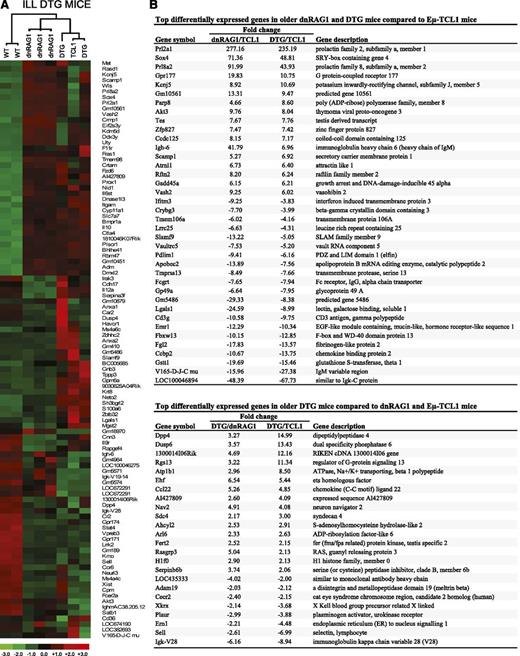

Identification of genes differentially expressed in WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells and CD19+CD5+ B cells from ill DTG mice and age-matched dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of a set of 102 genes that meet the filtering criterion which set the SD for logged data between 1.40 and 1000, and the expression level at >5 in 25% of the samples. (B) Pairwise comparisons were performed using the lower 90% confidence bound interval for genes with ±1.5-fold change filtering criterion. Genes with a mean expression value of <50 in a comparison pair were not included. A list of common genes among the 50 genes that display the greatest differential expression in CD19+CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice is shown in the top panel. A list of 24 genes that display the greatest differential expression (more than twofold) in CD19+CD5+ B cells DTG mice compared with both dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice is shown in the bottom panel.

Identification of genes differentially expressed in WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells and CD19+CD5+ B cells from ill DTG mice and age-matched dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice. (A) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of a set of 102 genes that meet the filtering criterion which set the SD for logged data between 1.40 and 1000, and the expression level at >5 in 25% of the samples. (B) Pairwise comparisons were performed using the lower 90% confidence bound interval for genes with ±1.5-fold change filtering criterion. Genes with a mean expression value of <50 in a comparison pair were not included. A list of common genes among the 50 genes that display the greatest differential expression in CD19+CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice is shown in the top panel. A list of 24 genes that display the greatest differential expression (more than twofold) in CD19+CD5+ B cells DTG mice compared with both dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice is shown in the bottom panel.

To identify specific genes that are differentially expressed between the sorted B-cell populations in the 12-week group, we performed a series of pairwise comparisons between the microarray data sets. First, we compiled the 50 genes showing the greatest differential expression for each pairwise comparison (25 up and 25 down), and generated a list of common genes that are differentially expressed between transgenic CD5+ B cells and WT B cells in all 3 comparisons (Figure 4B). Among the genes included on this list are cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (Ctla4; 8.4- to 16.9-fold increase), complement receptor 2 (Cr2 [CD21]; 4.5- to 5.4-fold decrease) and Fcer2a (CD23; 12- to 25-fold decrease). These differences were validated at the protein level by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 2A). Several other genes also displayed a consistent pattern of differential expression, including Pstpip2 (+11- to 14-fold), Cpm (−11- to 12-fold), Sell (−4- to 14-fold), and Lrrk2 (−18- to 24-fold).

Using the same approach, we next compared the gene expression profiles from dnRAG1 and DTG mice to those obtained from Eμ-TCL1 mice (Figure 4B). In this comparison, most genes showed a <10-fold difference in relative expression. Among the 17 common upregulated genes, 2 prolactin family members, Prl2a1 and Prl7c1, showed increased expression in CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 mice (57- and 3.6-fold, respectively) and DTG mice (53- and 4.4-fold, respectively) relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice. In addition, the gene identified as LOC100047053 showed elevated expression in CD5+ B cells from both dnRAG1 (12.07-fold) and DTG (7.01-fold) mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice. This gene is synonymous with Igκv6-32 (Igκv19-32) and was previously shown to be highly represented in the light chain repertoire of CD19+B220lo B cells in dnRAG1 mice,12 which likely explains its apparent upregulation in CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice. None of the 17 downregulated genes on this list showed >10-fold reduction in both pairwise comparisons.

We repeated these analyses with the older mice, focusing on differences between the transgenic CD5+ populations, although comparisons to WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells were also made (supplemental Table 4). First, we compared gene expression data obtained for CD5+ B cells from ill DTG and age-matched dnRAG1 mice to an older Eμ-TCL1 mouse (Figure 5B). As observed at 12 weeks, Prl2a1 was highly upregulated in CD5+ B cells from older dnRAG1 and ill DTG mice relative to the Eμ-TCL1 mouse (277- and 235-fold, respectively). Three additional genes, Sox4, Gpr177, and Prl8a2a, were also upregulated >10-fold in both dnRAG1 and DTG CD5+ B cells in this comparison. Quantitative PCR analysis of Prl2a1 and Sox4 expression in whole-spleen tissue obtained from 36-week-old WT and transgenic mice confirmed that both genes were overexpressed in dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to both WT and Eμ-TCL1 mice (Figure 6). By contrast, 12 genes were downregulated by >10-fold among older dnRAG1 and DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice (Figure 5B); only 1 non-Ig-related gene, Lgals1, appeared on the list of downregulated genes at both time points. We also performed individual pairwise comparisons between the CD5+ B-cell gene expression data from the older DTG and Eμ-TCL1 mice (supplemental Tables 5-6). This exercise unexpectedly revealed that CD5+ B cells from one of the DTG mice highly upregulated CD23 expression (32-fold) relative to the Eμ-TCL1 mouse (supplemental Table 6). This observation was confirmed by flow cytometry (supplemental Figure 6), and raises the possibility that CD23 expression may be induced in CD5+ B cells in some cases when DTG mice become ill.

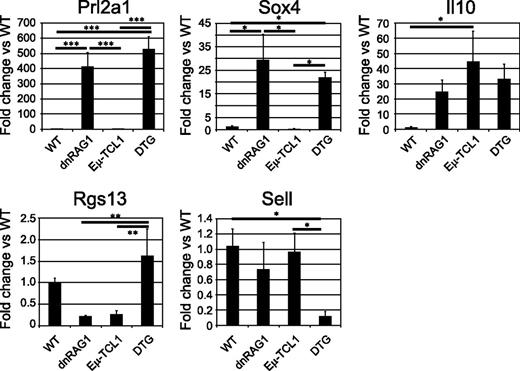

Validation of differentially expressed genes by quantitative PCR. The relative expression of Prl2a1, Il10, Sox4, Rgs13, and Sell in whole-spleen tissue of 36-week-old mice (n = 3/genotype) was measured by real-time quantitative PCR. Data are presented as mean fold change relative to WT mice; error bars represent the SEM. Significant differences between genotypes are indicated (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

Validation of differentially expressed genes by quantitative PCR. The relative expression of Prl2a1, Il10, Sox4, Rgs13, and Sell in whole-spleen tissue of 36-week-old mice (n = 3/genotype) was measured by real-time quantitative PCR. Data are presented as mean fold change relative to WT mice; error bars represent the SEM. Significant differences between genotypes are indicated (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

We next compared the gene expression data from ill DTG mice to age-matched dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice to identify genes that were upregulated or downregulated more than twofold in both pairwise comparisons which distinguish DTG mice from both dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice (Figure 5B). The expression of several of the identified genes in spleen tissue obtained from 36-week-old WT and transgenic mice was analyzed by quantitative PCR. These studies confirmed that Rgs13 and Sell expression was significantly different between DTG mice and one or both of the single-transgenic mice (Figure 6). The expression of other genes tested, including Dpp4, Ccl22, and Plaur, showed no significant differences between the transgenic animals.

Finally, we evaluated the expression of genes involved in BCR signaling22 and immune suppression,22,23 some of which are reportedly differentially expressed in CLL. Supervised hierarchical clustering analysis showed that these genes clearly differentiate WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells from transgenic CD19+CD5+ B cells at both time points (supplemental Figure 7). Several genes involved in modulating BCR signaling and known to be upregulated on CLL cells, including Cd5, Nfatc1,24 and Ptpn22,25 were also found to be upregulated on all transgenic CD19+CD5+ B cells compared with WT CD19+B220hiCD5− B cells. CD22, a negative regulator of BCR signaling that is also underexpressed in CLL,26,27 was downregulated at least 2.6-fold in CD5+ B cells at both time points, except in older Eμ-TCL1 mice where the difference was more modest (−1.2-fold). Some genes comprising a “tolerogenic signature” for CLL28,29 were also upregulated on transgenic CD19+CD5+ B cells at both time points and were increased in older mice, including Ctla4 (8.5-22 fold) and Il10 (4.9- to 14-fold) (Figure 4A and supplemental Table 6). Increased expression of both genes has been confirmed either at the protein level on CD5+ B cells (Ctla4; supplemental Figure 2A), or at the transcript level in whole-spleen tissue from transgenic mice (Il10; Figure 6).

Discussion

An emerging model for the etiology of CLL suggests that this disease originates through the monoclonal expansion of an antigen-experienced CD5+ B cell displaying polyreactivity and/or autoreactivity toward molecular motifs present on and often shared between apoptotic cells and bacteria.30 CD5+ B cells possessing this reactivity profile may develop through positive selection, such as peritoneal B1 cell and MZ B cell (in humans).31 Alternatively, they may emerge from conventional B2 lineage cells that are driven to express CD5 as a mechanism to attenuate chronic (auto)antigenic BCR signaling in response to failed attempts at silencing or reprogramming fortuitous germline-encoded BCR autoreactivity.6,9 If immune suppression is breached, the autoreactive B cell may enter the germinal center reaction, giving rise to somatically mutated B cells with a more restricted reactivity profile.32 In this way, both unmutated and mutated CLL may be traced to a common polyreactive/autoreactive adult B-lineage precursor,32 which is consistent with the observation that unmutated and mutated CLL show similar gene expression profiles.33

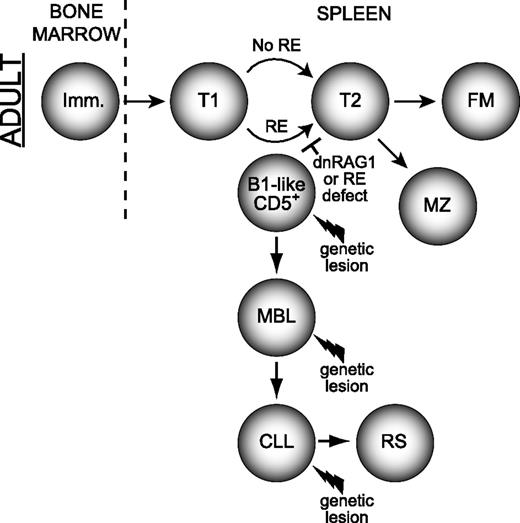

Receptor editing initiated in response to autoantigen exposure is thought to occur primarily during the immature/transitional T1 stage of B-cell development.34,35 We speculate that a stochastic mutation which impairs receptor editing induced in response to self-reactivity may enforce B-cell autoreactivity. Based on our previous work showing that dnRAG1 mice accumulate CD5+ B cells without progressing to overt CLL,12 we propose that autoreactivity enforced by a receptor editing defect could permit continued autoantigenic stimulation, and thereby promote sustained CD5 expression and persistence of a CD5+ B-cell clone. This possibility is consistent with the observation that CLL is often preceded by an indolent MBL that is phenotypically and cytogenetically similar to CLL.4,36 Although the initiating genetic mutation enforcing B-cell autoreactivity would normally expected to be rare and restricted to a single B-cell (thereby driving emergence of an MBL clone), developing B cells undergoing receptor editing (estimated at 25%-75% of B cells37 ) in dnRAG1 mice may frequently be blocked from successful editing by dnRAG1 expression. Thus, by facilitating a rate-limiting step in the emergence of CLL precursors, dnRAG1 expression may accelerate CLL progression in Eμ-TCL1 mice. If so, one might predict that the clonal B-cell repertoire in ill DTG mice should be more diverse than ill Eμ-TCL1 mice. Indeed, the observation that DTG mice show a higher number of unique productively rearranged heavy and light chain genes amplified by PCR lends support to this idea (supplemental Tables 1-2). We recognize that the absence of recurrent RAG mutations in CLL38 argues that CLL does not arise through defects in RAG activity. However, we emphasize that autoreactivity may be enforced by RAG-independent mutations which disrupt any of the pathways involved in initiating or completing receptor editing, or eliminating autoreactive B cells that fail to successfully edit. The same principle also applies for defects in receptor revision postulated to occur in B cells in response to acquiring autoreactivity by somatic hypermutation. Once enforced autoreactivity is established, subsequent genetic lesions (modeled here by Eμ-TCL1 expression) may promote further expansion and/or transformation of the CD5+ B cell. A simplified model summarizing the etiology and progression of CLL promoted by impaired receptor editing is shown in Figure 7. While this model suggests that autoantigenic stimulation induces receptor editing, cell-autonomous signaling mediated by certain intrinsically autoreactive/polyreactive heavy chains showing recurrent usage in CLL might also initiate this process.40 One-way cell-autonomous signaling could normally be attenuated is through light chain receptor editing to permit selection of “editor” light chains that neutralize interactions mediated by HCDR3. Studies of mice expressing an IgH transgene specific for dsDNA provide precedence for this possibility.41 We speculate that CLL cells may retain cell-autonomous signaling capacity because noneditor light chains have either been positively selected or failed to be replaced by receptor editing.

Model for how defects in receptor editing can promote development of MBL and CLL. Non–self-reactive immature B cells arriving from the bone marrow progress normally through the immature/transitional stages of B-cell development where receptor editing normally occurs. An immature/T1 B-cell possessing an autoreactive specificity normally subjected to editing may acquire a spontaneous mutation that impairs receptor editing (RE), (modeled here by dnRAG1 expression), which enforces receptor specificity and leads the B cell to retain or adopt a CD5+ B1-like (and CLL-like) phenotype. The cell may persist or accumulate as an MBL, which may or may not require other mutations, such as those causing TCL1 overexpression. Additional genetic lesions may promote MBL evolution to CLL and perhaps subsequently to RS.39 A similar series of events may also occur in post–germinal center B cells attempting to undergo receptor revision after having acquired autoreactivity during somatic hypermutation (not shown). T, transitional B cell; FM, follicular mature B cell; B1, B1 B cell; RS, Richter syndrome.

Model for how defects in receptor editing can promote development of MBL and CLL. Non–self-reactive immature B cells arriving from the bone marrow progress normally through the immature/transitional stages of B-cell development where receptor editing normally occurs. An immature/T1 B-cell possessing an autoreactive specificity normally subjected to editing may acquire a spontaneous mutation that impairs receptor editing (RE), (modeled here by dnRAG1 expression), which enforces receptor specificity and leads the B cell to retain or adopt a CD5+ B1-like (and CLL-like) phenotype. The cell may persist or accumulate as an MBL, which may or may not require other mutations, such as those causing TCL1 overexpression. Additional genetic lesions may promote MBL evolution to CLL and perhaps subsequently to RS.39 A similar series of events may also occur in post–germinal center B cells attempting to undergo receptor revision after having acquired autoreactivity during somatic hypermutation (not shown). T, transitional B cell; FM, follicular mature B cell; B1, B1 B cell; RS, Richter syndrome.

The finding that DTG mice more closely resemble dnRAG1 mice than Eμ-TCL1 mice with respect to gene expression profiles at 12 weeks (Figure 4) and serum Ig levels at both time points (Figure 2B) argues that CD5+ B-cell accumulation in DTG mice is driven primarily by dnRAG1 expression. Thus, CD5+ B cells in Eμ-TCL1 mice and dnRAG1/DTG mice appear to initially emerge by slightly different mechanisms, yet their gene expression patterns remain more similar to one another than to other normal splenic B-cell populations (supplemental Figure 5). One gene that may contribute to this distinction is Prl2a1, which is highly expressed in CD5+ B cells from dnRAG1 and DTG mice compared with Eμ-TCL1 mice. Emerging evidence suggests prolactin signaling may regulate B-cell tolerance mechanisms42 by promoting survival of T1 transitional B cells that are normally subjected to negative selection at this stage.43 We speculate that murine autoreactive B cells transiently produce Prl2a1 as a prosurvival factor to facilitate receptor editing, but in dnRAG1 and DTG mice, Prl2a1 expression is sustained because receptor editing is blocked by dnRAG1 expression. Because humans do not have a Prl2a1 homolog, its role in B-cell development and CLL cannot be ascertained; whether an orthologous prolactin/growth hormone family member assumes its function in human B cells remains unclear.

Although we have not established specific factors responsible for accelerating disease progression in DTG mice, we have identified genes that are differentially expressed in CD5+ B cells from DTG mice relative to their single-transgene counterparts which may warrant further study. For example, both Dpp4 upregulation and Sell downregulation reportedly correlate with poor prognosis in human CLL,44,45 which is consistent with the earlier onset of disease observed in DTG mice relative to Eμ-TCL1 mice. However, we cannot exclude the possible contribution of T cells in accelerating disease progression in DTG mice because T cells have been implicated in CLL development in Eμ-TCL1 mice,46,47 and splenic T cells in DTG mice are quantitatively elevated compared with both dnRAG1 and Eμ-TCL1 mice at 36 weeks. Establishing how T cells regulate disease progression in DTG mice, while beyond the scope of the present study, is of interest for future investigations.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Nebraska Medical Center Microarray Core Facility staff for microarray hybridization services, and Dr Steven Lundy for manuscript review. Support from the Health Future Foundation, the Nebraska LB506 and LB595 Cancer and Smoking Disease Research Programs, and the Nebraska LB692 Biomedical Research Program is gratefully acknowledged.

The National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provided support for research laboratory construction (C06 RR17417-01) and the Creighton University Animal Resource Facility (G20RR024001). The University of Nebraska Medical Center Microarray Core Facility receives support from the NCRR (5P20RR016469, RR018788-08) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (8P20GM103427, GM103471-09).

This publication’s contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Authorship

Contribution: V.K.N., V.L.P., M.D.K., D.K.A., G.A.P., and N.M.S. performed research and analyzed data; H.N. evaluated histopathology; and P.C.S. and V.K.N. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for D.K.A. is Accuri Cytometers, 173 Parkland Plaza, Ann Arbor, MI.

Correspondence: Patrick C. Swanson, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Creighton University, 2500 California Plaza, Omaha, NE 68178; e-mail: pswanson@creighton.edu.