Abstract

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway has emerged as a critical regulator of dendritic cell (DC) development and function. The kinase mTOR is found in 2 distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. In this study, we show that mTORC1 but not mTORC2 is required for epidermal Langerhans cell (LC) homeostasis. Although the initial seeding of the epidermis with LCs is not affected, the lack of mTORC1 activity in DCs by conditional deletion of Raptor leads to a progressive loss of LCs in the skin of mice. Ablation of mTORC2 function by deletion of Rictor results in a modest reduction of LCs in skin draining lymph nodes. In young mice Raptor-deficient LCs show an increased tendency to leave the skin, leading to a higher frequency of migratory DCs in skin draining lymph nodes, indicating that the loss of LCs results from enhanced migration. LCs lacking Raptor are smaller and display reduced expression of Langerin, E-cadherin, β-catenin, and CCR7 but unchanged levels of MHC-II, ruling out enhanced spontaneous maturation. Ki-67 and annexin V stainings revealed a faster turnover rate and increased apoptosis of Raptor-deficient LCs, which might additionally affect the preservation of the LC network. Taken together our results show that the homeostasis of LCs strictly depends on mTORC1.

Key Points

mTORC1 activity in DCs by conditional deletion of Raptor leads to a progressive loss of LCs in the skin of mice.

mTORC1 but not mTORC2 is required for epidermal LC homeostasis.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are specialized antigen-presenting cells essential for the initiation of adaptive immune responses and the maintenance of tolerance to self-antigens.1 The outcome of antigen recognition by a T cell is dependent on the expression of distinct costimulatory and coinhibitory molecules as well as pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines expressed by the DC.2 DCs develop from hematopoietic stem cells through specialized progenitor cells. Under steady-state conditions 3 major types of DCs differing in their location, phenotype, and function exist, the plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), lymphoid organ resident DCs (rDCs), and peripheral tissue migratory DCs (mDCs).3 In skin draining lymph nodes (sLNs) the mDC subset includes epidermal Langerhans cells (LCs) and Langerin+ and Langerin− dermal DCs (dDCs). LCs and Langerin+ dDCs can be distinguished by the absence and presence of the integrin αE subunit CD103, respectively.4

In recent years it has become increasingly evident that the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway plays an important role in DC development and function.5 The mammalian target of rapamycin mTOR is a conserved serine/threonine kinase found in 2 distinct multiprotein complexes termed mTORC1 and mTORC2.6 Raptor and Rictor are components essential for the assembly and the specific functions of mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively. The macrolide drug rapamycin specifically blocks the function of mTORC1. Although originally described as rapamycin insensitive,7,8 increasing evidence indicates that prolonged rapamycin treatment also inhibits mTORC2.9,10 MTORC1 is regulated by extracellular signals, which trigger the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K) and its downstream effector Akt. The Akt-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 abrogates the GAP activity of the TSC1/2 complex toward the GTPase Rheb, thereby permitting the activation of Rheb and subsequently of mTORC1. MTORC2 is likewise stimulated by growth factors and the PI3K, but signaling steps beyond PI3K are distinct from those upstream of mTORC1 and unknown.11,12 MTORC2 is involved in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton.7,8 Furthermore mTORC2 directly phosphorylates Akt at Ser473, which is required for full activation.13-16 MTORC1 controls cell growth, proliferation, and survival by promoting protein synthesis by activating S6K1 and by inhibiting the translational repressor eIF4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1).6

Treatment of DCs with rapamycin confers maturation resistance and drives the generation of tolerogenic DCs with poor T-cell stimulatory capacity.17-19 In pDCs mTORC1 is essential for the production of type I IFNs.20,21 Interestingly, inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin promotes the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, and inhibits the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.22-24 Recently it was shown that deletion of Rictor also leads to an increased production of inflammatory cytokines on LPS-stimulation resulting from the attenuated Akt activation and consequently the reduced inactivation and nuclear exclusion of FoxO1.25 Besides its functions as a regulator of cytokine production, mTOR has been shown to influence DC development and survival.26-28

Most of the aforementioned studies investigated the role of mTOR in cultured bone-marrow derived DCs in vitro, or specific DC subsets, such as plasmacytoid DCs (pDC). However, at present nothing is known on the function of mTOR in the various subsets of skin DCs, including Langerhans cells (LCs), the prototype migratory DC subset. To analyze mTORC1 and mTORC2 in skin DCs, we studied these DC-subtypes in mice lacking Raptor or Rictor expression specifically in DCs. Our results identify a novel role of mTORC1 as a regulator of LC homeostasis.

Methods

Mice

To generate mice with DCs deficient in mTORC1 or mTORC2 function we crossed previously described raptorfl/fl and rictorfl/fl mice29 with CD11c-Cre transgenic mice (Cre) expressing the Cre-recombinase under the control of the DC-specific CD11c-promoter30 [CD11c-Cre-raptorfl/fl (rapΔ/Δ) and CD11c-Cre-rictorfl/fl (ricΔ/Δ)]. Mice were bred and housed at the animal facilities of the Institute for Immunology (LMU, Munich, Germany) and treated in accordance with established guidelines of the Regional Ethics Committee of Bavaria.

Western blotting

To obtain total lysates, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 1% Igepal and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentration was quantified with Quant-iT protein assay kit in a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Rabbit antibodies detecting Raptor, Rictor (53A2), phospho-Akt (Ser473; 193H12), total Akt, phospho-GSK-3α/β (Ser21/9; 37F11), and actin were from Cell Signaling Technologies. HRP-conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG was from Rockland. Signal intensities were quantified using ImageJ 1.46 software (National Institutes of Health).

Cell isolation and purification from lymph nodes

Single-cell suspensions from lymph nodes were obtained by mechanical disruption using a pestle followed by enzymatic digestion in serum-free RPMI medium containing Liberase CI (0.42 mg/mL) and DNase I (0.2 mg/mL, both from Roche) for 20 minutes at 37°C. Cells were passed through a 70-μm nylon mesh strainer. Cells were counted on a cell counter (Beckman Coulter).

Cell isolation from skin

Ears were split into dorsal and ventral halves. For crawl-out assays from whole skin explants, ear halves were floated dermal side down on RPMI medium containing 10% heat inactivated FCS, 1% PenStrep, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 ng/mL GM-CSF (RPMI complete). Cells were left to crawl-out for 48 hours in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 hours ear halves were transferred to fresh medium. To separate the epidermis from the dermis, ear halves were floated on RPMI containing 2.4 U/mL Dispase II (Roche) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The epidermis was peeled off, cut into small pieces, and further digested with 1.5 mg/mL collagenase IV (Worthington) in RPMI. The dermis was cut into small pieces and digested in a mix containing 0.05% DNase I, 0.27% collagenase XI, 0.0027% hyaluronidase VI, and 10mM HEPES in RPMI for 1 hour at 37°C. Alternatively, epidermis and dermis were separately applied for crawl-out assays as described.

Generation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells

Femurs and tibiae were flushed with IMDM and erythrocytes were lysed by incubation in ACK buffer for 2 minutes at room temperature. One × 107 bone marrow cells were plated in 10 mL IMDM containing 10% heat inactivated FCS, 2mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 50μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 20 ng/mL GM-CSF (IMDM complete) in Petri dishes. On days 3, 7, and 10 suspension cells and loosely adherent cells were dislodged by gentle pipetting and adherent cells were subsequently released by incubation in cold PBS containing 1mM EDTA. Cells (7.5 × 106) were reseeded in 10 mL fresh IMDM complete per 10-cm dish.

Immunohistochemistry

Epidermal sheets were prepared as described. Sheets were fixed with acetone for 5 minutes at room temperature, rehydrated with PBS, blocked in PBS containing 0.25% BSA and 10% FCS, and stained with biotinylated anti–I-A/I-E and where indicated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.2 in blocking buffer containing Fc-block followed by staining with DAPI and Cy3–conjugated streptavidin. Sheets were mounted in Fluoromount (Southern Biotechnology) and analyzed on a BX41TF-5 microscope with a Fluo-View II Digital camera and CELL-F software (Olympus).

Flow cytometry, antibodies, biochemicals, and kits

Unless otherwise stated, antibodies were purchased from eBioscience or BD Bioscience. The mAbs used for flow cytometry were FITC-/Alexa Fluor 488, PE, PerCP-/PE-Cy5.5-, PE-Cy7-, APC-/Alexa Fluor 647, or Pacific blue-/eFluor450–conjugated anti–mouse I-A/I-E (M5 114.15.2), F4/80 (BM8), CD8α (53-6.7), CD11c (N418), CD40 (1C10), CD45 (30F11), CD45.2 (104), CD80 (1610A1), CD86 (GL1), CD103 (2E7), CD197 (CCR7, 4B12), CD207 (Langerin, clone 929F3, Dendritics), CD317 (PDCA-1/Bst2, eBio927), CD324 (E-Cadherin, DECMA-1), CD326 (EpCAM, G8.8), β-catenin (15B8), and IL-12p40 (C17.8). Violet-1 fixable dead cell marker was purchased from Invitrogen, rapamycin was from Sigma-Aldrich, CpG was from Invivogen, and GolgiStop was from BD Bioscience. Staining of surface markers was performed with 1 to 5 × 106 cells in cold staining buffer (PBS/2% FCS/0.01% N3) for 20 minutes on ice. CCR7 was stained for 30 minutes at 37°C. All staining mixes contained Fc-block (anti-CD16/CD32, FcγRII/III). Intracellular or intranuclear stainings were performed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience) or the FoxP3 staining buffer set (eBioscience), respectively. Annexin-V (Bender MedSystems), 7-AAD (BD Bioscience), Ki-67 (BD Bioscience), and FITC-VAD-FMK (CaspACE, Promega) staining kits were applied according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS Canto II instrument (BD Bioscience) and analyzed with FlowJo 8.8.6 software (TreeStar).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed and plotted using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software). Statistical analysis was done with student t test for all analyses. A P value of P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

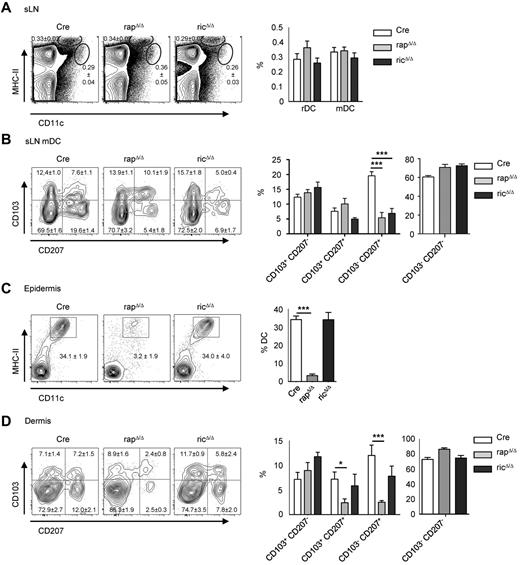

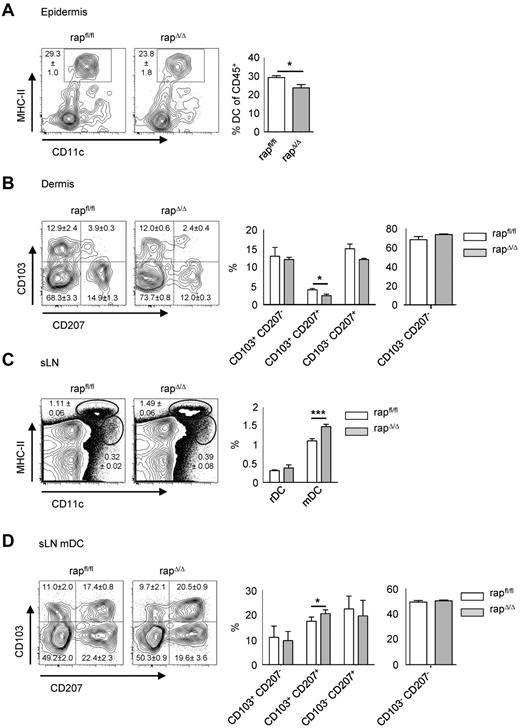

Deletion of Raptor leads to a strong reduction of epidermal LCs

To examine the consequences of Raptor and Rictor deletion in DCs (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) we analyzed DC subsets in lymph nodes by flow cytometry. In peripheral lymphoid organs, the tissue derived mDC subset is characterized by high-surface MHC-II–expression and an intermediate expression of the integrin αx subunit CD11c, whereas lymphoid tissue rDCs express lower levels of MHC-II and high levels of CD11c. In sLNs, the frequency of rDCs (CD11c+ MHC-II+) and mDCs (CD11cint MHC-IIhigh) DCs is not significantly altered in both mouse strains compared with Cre controls (Figure 1A). The mDC fraction in sLNs can be further subdivided into CD207+ (Langerin+) CD103− DCs representing migratory epidermal LCs and CD207+ CD103+ DCs representing Langerin-positive dDCs. Staining of sLN cells with mAbs for CD207 and CD103 revealed an approximately 3-fold reduction of migratory LCs from rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ mice compared with Cre control mice (Figure 1B). To determine the frequency of LCs in the skin we performed FACS analyses of single-cell suspensions from enzymatically digested epidermis and dermis derived from ear skin. As shown in Figure 1C there is an approximately 10-fold decrease of DCs in the epidermis of rapΔ/Δ mice. Accordingly, the frequency of transmigrating LCs in the dermis is diminished as well (Figure 1D). In the dermis, also the frequency of Langerin+ CD103+ dDCs is reduced to one-third. RicΔ/Δ mice contain normal numbers of DCs in the epidermis. In the dermis however, there is a modest reduction of transmigrating LCs despite the normal frequency of LCs in the epidermis. The reduced frequency of ricΔ/Δ LCs in sLNs and the weak reduction in the dermis in spite of normal numbers in the epidermis might be because of a migratory defect of these cells, because a function of mTORC2 in the regulation of migration has been described.7,8

Deletion of Raptor results in a reduction of migratory LCs. (A) FACS analysis of rDC (CD11c+ MHC-II+) and mDC (CD11cint MHC-IIhigh) subsets in sLNs from Cre, rapΔ/Δ, and ricΔ/Δ mice. Populations shown in plots are gated on live cells. Bar graph displays mean frequency ± SEM of rDCs and mDCs (N = 17-21 mice per group). (B) Analysis of Langerin (CD207) and CD103 expression by mDCs in sLNs. Populations in plots are gated on live mDCs as shown in panel A. Numbers and bar graphs indicate mean frequency of cells in the respective quadrant ± SEM. Data were combined from 3 independent experiments with similar results (N = 6 mice per group). (C-D) DCs in the epidermis (C) and dermis (D) of enzymatically digested ear skin from Cre, rapΔ/Δ, and ricΔ/Δ mice. Populations in plots are gated on CD45+ cells (C) and CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells (D). Numbers and bar graphs indicate the mean frequency of cells in the respective gate or quadrant ± SEM. Data were combined from 7 (C) and 4 (D) independent experiments with similar results (panel C: N = 15 mice for Cre, N = 13 mice for rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ; panel D: N = 8 mice for Cre and rapΔ/Δ, N = 5 mice for ricΔ/Δ).

Deletion of Raptor results in a reduction of migratory LCs. (A) FACS analysis of rDC (CD11c+ MHC-II+) and mDC (CD11cint MHC-IIhigh) subsets in sLNs from Cre, rapΔ/Δ, and ricΔ/Δ mice. Populations shown in plots are gated on live cells. Bar graph displays mean frequency ± SEM of rDCs and mDCs (N = 17-21 mice per group). (B) Analysis of Langerin (CD207) and CD103 expression by mDCs in sLNs. Populations in plots are gated on live mDCs as shown in panel A. Numbers and bar graphs indicate mean frequency of cells in the respective quadrant ± SEM. Data were combined from 3 independent experiments with similar results (N = 6 mice per group). (C-D) DCs in the epidermis (C) and dermis (D) of enzymatically digested ear skin from Cre, rapΔ/Δ, and ricΔ/Δ mice. Populations in plots are gated on CD45+ cells (C) and CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells (D). Numbers and bar graphs indicate the mean frequency of cells in the respective gate or quadrant ± SEM. Data were combined from 7 (C) and 4 (D) independent experiments with similar results (panel C: N = 15 mice for Cre, N = 13 mice for rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ; panel D: N = 8 mice for Cre and rapΔ/Δ, N = 5 mice for ricΔ/Δ).

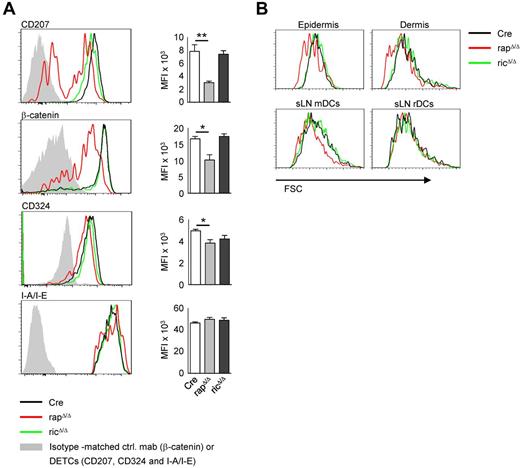

RapΔ/Δ LCs show a reduced cell size and altered expression of surface and intracellular markers

To further assess the phenotype of rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ LCs we analyzed the expression of surface and intracellular LC markers. As shown in Figure 2A, a substantial proportion of approximately 40% of DCs in the epidermis of rapΔ/Δ mice are Langerin-negative and the expression of Langerin in the positive fraction is lower than in Cre controls. The steady-state expression of β-catenin is markedly decreased and the expression of E-Cadherin (CD324) is modestly decreased in rapΔ/Δ, LCs whereas the expression of MHC-II (I-A/I-E) is not affected. No significant differences in the expression of any of these marker were detected in ricΔ/Δ LCs. MTORC1 is known to regulate cell growth and its inhibition leads to a reduced cell size.31 We therefore analyzed the forward scatter (FSC) as a measure of cell size of DCs from rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ mice. As shown in Figure 2B, DCs from the epidermis and dermis of rapΔ/Δ mice show a markedly reduced FSC compared with Cre DCs, whereas ricΔ/Δ DCs do not differ from Cre DCs. No differences in cell size were found for any non-DC cell type from skin or lymphoid tissue (data not shown). Interestingly we found a markedly decreased size of rapΔ/Δ mDCs but not rDCs in sLNs (Figure 2B). This result is probably because of the longer lifetime of the migratory subsets entering from peripheral tissues compared with the rather short-lived resident DC fraction. The longer lifetime of mDCs should result in a stronger phenotype because of a more effective knockout especially in case if the mRNA or the protein of the target gene is relatively stable. Accordingly the cell size of splenic rapΔ/Δ cDCs, pDCs and MΦs is indistinguishable from Cre controls (data not shown). We observed a comparably diminished cell size of all mDC subtypes analyzed, including LCs and CD207+ and CD207− dDCs (data not shown).

Epidermal LCs of rapΔ/Δ mice show a reduced expression of Langerin and β-catenin and a reduced cell size. (A) FACS analysis of epidermal LCs isolated by enzymatic digestion. Histograms show CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells (LCs) from the epidermis of Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line), and ricΔ/Δ (green line) mice. Gray solid graphs show CD45+ non DCs (DETCs) in the histograms of CD207, CD324 and I-A/I-E or an isotype-matched control antibody staining in the histogram showing β-catenin expression. Bar graphs represent MFI ± SEM of N = 4 mice per group of the respective marker. Data were combined from 2 of 4 independent experiments with similar results. (B) FSC of epidermal and dermal DCs isolated by crawl-out (top panel) and mDCs and rDCs from sLNs (bottom panel) of Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line) and ricΔ/Δ (green line) mice. Cells were gated on CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ (epidermis and dermis), MHC-IIhigh CD11cint (mDCs) and MHC-II+ CD11c+ (rDCs). Data shown are representative of ≥ 3 experiments with at least 2 mice per group.

Epidermal LCs of rapΔ/Δ mice show a reduced expression of Langerin and β-catenin and a reduced cell size. (A) FACS analysis of epidermal LCs isolated by enzymatic digestion. Histograms show CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells (LCs) from the epidermis of Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line), and ricΔ/Δ (green line) mice. Gray solid graphs show CD45+ non DCs (DETCs) in the histograms of CD207, CD324 and I-A/I-E or an isotype-matched control antibody staining in the histogram showing β-catenin expression. Bar graphs represent MFI ± SEM of N = 4 mice per group of the respective marker. Data were combined from 2 of 4 independent experiments with similar results. (B) FSC of epidermal and dermal DCs isolated by crawl-out (top panel) and mDCs and rDCs from sLNs (bottom panel) of Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line) and ricΔ/Δ (green line) mice. Cells were gated on CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ (epidermis and dermis), MHC-IIhigh CD11cint (mDCs) and MHC-II+ CD11c+ (rDCs). Data shown are representative of ≥ 3 experiments with at least 2 mice per group.

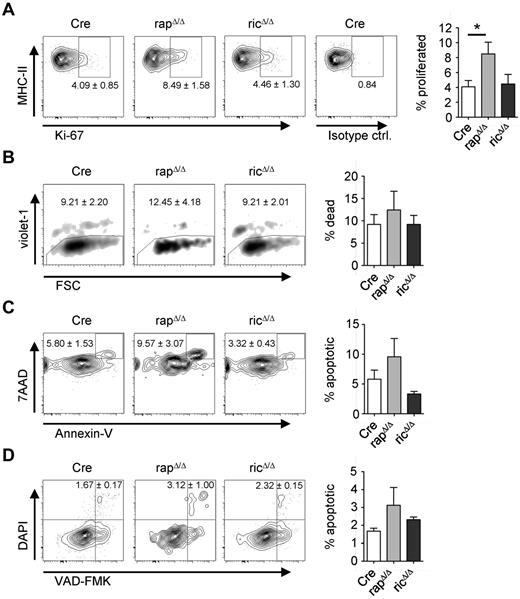

Raptor-deficient LCs exhibit a higher turnover rate and an elevated frequency of apoptosis

In the steady-state, LCs constitutively migrate to sLNs and self-renew in situ by a slow proliferation. Because mTORC1 function is involved in cell-cycle regulation, we hypothesized that the ability to proliferate might be affected in rapΔ/Δ LCs. To test this hypothesis we performed FACS analyses of Ki-67 stainings of epidermal cells from adult mice. In CD11c-Cre mice we detected a proportion of approximately 4% Ki-67+ LCs confirming earlier observations.32 Although no significant differences are present in ricΔ/Δ mice, we found the proportion of proliferating LCs doubled in rapΔ/Δ mice to approximately 8.5% Ki-67+ LCs (Figure 3A). These results indicate that the lack of LCs is not caused by a lower proliferation rate of the cells. Therefore, we next sought to determine the frequency of apoptosis of epidermal LCs. For this purpose we performed annexin V stainings of epidermal cells. As shown in Figure 3B, violet-1 or DAPI stainings revealed no significant difference in the presence of dead DCs isolated by crawl-out from the epidermis of rapΔ/Δ or ricΔ/Δ mice. Although these differences were statistically not significant, staining with annexin V and 7-AAD, or with VAD-FMK and DAPI, however indicated a slightly elevated proportion of apoptotic rapΔ/Δ DCs compared with Cre or ricΔ/Δ (Figure 3C-D).

Raptor-deficient LCs have a higher frequency of proliferation and apoptosis. Analysis of proliferation (A), viability (B) and apoptosis (C-D) of epidermal DCs. DCs were isolated by enzymatic digestion (A) or by crawl-out from the epidermis (B-D) of Cre, rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ mice. Populations are gated on CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+/CD207+ cells. Numbers and bar graphs indicate the mean frequency ± SEM of cells within the respective gate or quadrant (A,C-D) or out of the gate (B). (A) Ki-67+ cells represent recently divided LCs. The very right plot shows staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. Data were combined from 2 independent experiments with similar results (N = 4 mice per group). (B) Violet-1+ cells represent dead DCs. One representative of 4 independent experiments with similar results is shown (N = 3 mice per group). (C) Annexin V+ 7AAD+ cells represent apoptotic DCs. Data are combined from 3 independent experiments with similar results (N = 6 mice per group). (D) VAD-FMK+ DAPI+ cells represent apoptotic DCs (N = 3 mice per group).

Raptor-deficient LCs have a higher frequency of proliferation and apoptosis. Analysis of proliferation (A), viability (B) and apoptosis (C-D) of epidermal DCs. DCs were isolated by enzymatic digestion (A) or by crawl-out from the epidermis (B-D) of Cre, rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ mice. Populations are gated on CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+/CD207+ cells. Numbers and bar graphs indicate the mean frequency ± SEM of cells within the respective gate or quadrant (A,C-D) or out of the gate (B). (A) Ki-67+ cells represent recently divided LCs. The very right plot shows staining with an isotype-matched control antibody. Data were combined from 2 independent experiments with similar results (N = 4 mice per group). (B) Violet-1+ cells represent dead DCs. One representative of 4 independent experiments with similar results is shown (N = 3 mice per group). (C) Annexin V+ 7AAD+ cells represent apoptotic DCs. Data are combined from 3 independent experiments with similar results (N = 6 mice per group). (D) VAD-FMK+ DAPI+ cells represent apoptotic DCs (N = 3 mice per group).

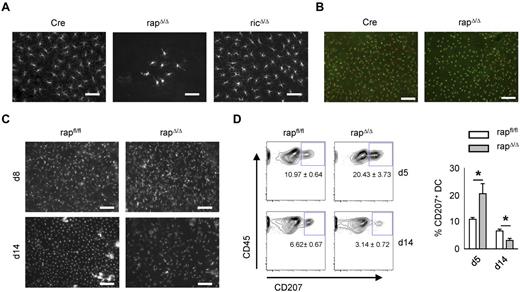

Raptor-deficient LCs decline over time

To examine the appearance and distribution of LCs within the epidermis of rapΔ/Δ mice we performed histologic stainings of epidermal sheets from ear skin. Staining of MHC-II to visualize LCs revealed that the scarce LCs in the epidermis of adult rapΔ/Δ mice are not regularly spread but are concentrated in islets of variable cell number ranging from 1 to several hundred cells (Figure 4A). LCs from adult ricΔ/Δ mice are indistinguishable from Cre controls regarding cell number, spatial distribution, and morphology. Despite the strong reduction of LCs we found a normal cell number and distribution of dendritic epidermal T cells in rapΔ/Δ epidermis (Figure 4B). The epidermis is initially seeded with CD11c− LC precursors around embryonic day 18. These cells gain CD11c, MHC-II, and Langerin-expression as well as a dendritic morphology soon after birth and undergo a massive burst of proliferation between postnatal days 2 and 7.32 To assess whether the low number of LCs in adult rapΔ/Δ epidermis is because of a decrease of cells over time or is caused by a lack of proliferation in the early phase, we examined the epidermis at day 8 after birth histologically. No significant differences in LC numbers and distribution were observed between CD11c-Cre nontransgenic (rapfl/fl) and transgenic (rapΔ/Δ) littermates at the age of 8 days (Figure 4C). In contrast, the abundance of LCs in the epidermis of day 14 rapΔ/Δ littermates was already reduced to less than 50% compared with CD11c-Cre nontransgenic littermates (Figure 4C). However the cells are not concentrated in clusters as in older rapΔ/Δ mice but are spatially regularly distributed. Accordingly, crawl-out assays from whole-skin explants showed an approximately 50% diminished proportion of Langerin+ DCs at the age of 14 days (Figure 4D). In contrast, at day 5 the fraction of Langerin+ DCs from rapΔ/Δ mice was not diminished, but exceeded that of nontransgenic littermates by 50% (Figure 4D). These data indicate that LCs from rapΔ/Δ mice might have a higher rate of spontaneous emigration than control littermates.

Progressive loss of Raptor but not Rictor-deficient epidermal LCs. (A) Microscopy of epidermal sheets from adult Cre, rapΔ/Δ, and ricΔ/Δ mice. LCs were visualized by MHC-II staining. The size bar corresponds to 50 μm. Original magnification ×40. (B) Epidermal sheets from adult Cre and rapΔ/Δ stained with mAbs for MHC-II in red (LCs) and CD45.2 in green (DETCs and LCs). The size bar corresponds to 100 μm. Original magnification ×20. (C) Epidermal sheets from a day 8 (top panel) and a day 14 (bottom panel) rapfl/fl litter were stained as in panel A. The size bar corresponds to 100 μm. Original magnification ×20. (D) Skin derived DCs isolated by crawl-out from whole ear skin of a day 5 (top panel) and a day 14 (bottom panel) rapfl/fl litter. Populations shown were gated on CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells. The mean frequency of CD207+ cells ± SEM of N = 2 to 4 mice per group is indicated under the gate and in the bar graph on the right.

Progressive loss of Raptor but not Rictor-deficient epidermal LCs. (A) Microscopy of epidermal sheets from adult Cre, rapΔ/Δ, and ricΔ/Δ mice. LCs were visualized by MHC-II staining. The size bar corresponds to 50 μm. Original magnification ×40. (B) Epidermal sheets from adult Cre and rapΔ/Δ stained with mAbs for MHC-II in red (LCs) and CD45.2 in green (DETCs and LCs). The size bar corresponds to 100 μm. Original magnification ×20. (C) Epidermal sheets from a day 8 (top panel) and a day 14 (bottom panel) rapfl/fl litter were stained as in panel A. The size bar corresponds to 100 μm. Original magnification ×20. (D) Skin derived DCs isolated by crawl-out from whole ear skin of a day 5 (top panel) and a day 14 (bottom panel) rapfl/fl litter. Populations shown were gated on CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ cells. The mean frequency of CD207+ cells ± SEM of N = 2 to 4 mice per group is indicated under the gate and in the bar graph on the right.

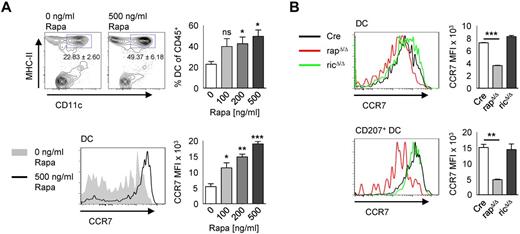

Raptor-deficient DCs are migratory and efficiently enter sLNs

Rapamycin treatment leads to a selective up-regulation of CCR7 and an enhanced migration of DCs to lymph nodes.33 Accordingly, when crawl-out assays from whole-skin explants were performed in presence of rapamycin, we found the frequency of DCs increasing with raising concentrations of rapamycin (Figure 5A). Furthermore, we confirmed the enhanced up-regulation of CCR7 with increasing concentrations of rapamycin. However, Langerin+ DCs from rapΔ/Δ mice isolated by crawl-out show a lower expression of CCR7 than Cre controls, whereas the expression in ricΔ/Δ mice was equal to Cre (Figure 5B). This result rules out enhanced CCR7-dependent migration of rapΔ/Δ LCs from the epidermis as cause of LC-loss. If the reduced number of LCs in rapΔ/Δ mice results from enhanced emigration from the epidermis, there should be a concomitant accumulation of migratory LCs in the sLNs at early time points. To assess this question we examined epidermis, dermis, and sLNs from rapΔ/Δ mice at the age of 12 days (Figure 6). At this time point the fraction of LCs in the epidermis was already reduced by approximately 20% in rapΔ/Δ compared with rapfl/fl littermates (Figure 6A), whereas the frequency of migrating LCs in the dermis and in the sLNs was not significantly altered (Figure 6B-D). Further analysis of the different DC subtypes showed that only the frequency of CD103+ CD207+ dDCs was significantly reduced in the dermis and significantly raised in the sLNs (Figure 6B-D). In the sLNs at day 12, the fraction of mDCs was significantly raised in rapΔ/Δ animals compared with rapfl/fl littermates arguing eventually for a higher migration rate of all migratory DCs rather than of LCs specifically (Figure 6C). These observations show that rapΔ/Δ LCs are able to efficiently migrate toward and home into sLNs. The loss of epidermal LCs over time might therefore be caused by the slower replenishment of these cells compared with the faster turnover of dDCs. Taken together these data indicate that the progressive loss of epidermal LCs in rapΔ/Δ mice results from increased cell death as well as from enhanced emigration of the cells from the skin.

Raptor-deficient DCs express less CCR7. (A) Cells from control mice were left to migrate into medium containing 0, 100, 200, or 500 ng/mL rapamycin. Populations in plots are gated on CD45+ cells. The mean frequency ± SEM of CD11c+ MHC-II+ cells is indicated below the gate and in the bar graph on the right (N = 3 mice per group). The histogram below shows the expression of CCR7 by DCs gated as shown in the top panel without or with 500 ng/mL rapamycin. The bar graph on the right represents the MFI ± SEM of CCR7 with increasing concentrations of rapamycin. (B) gated as shown in panel A. Histograms show the expression of CCR7 by skin derived DCs (top panel) or by CD207+ DCs (bottom panel) isolated by crawl-out from whole skin explants of Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line), and ricΔ/Δ (green line) mice. Bar graphs represent the MFI ± SEM of N = 2 mice per group. One representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results is shown.

Raptor-deficient DCs express less CCR7. (A) Cells from control mice were left to migrate into medium containing 0, 100, 200, or 500 ng/mL rapamycin. Populations in plots are gated on CD45+ cells. The mean frequency ± SEM of CD11c+ MHC-II+ cells is indicated below the gate and in the bar graph on the right (N = 3 mice per group). The histogram below shows the expression of CCR7 by DCs gated as shown in the top panel without or with 500 ng/mL rapamycin. The bar graph on the right represents the MFI ± SEM of CCR7 with increasing concentrations of rapamycin. (B) gated as shown in panel A. Histograms show the expression of CCR7 by skin derived DCs (top panel) or by CD207+ DCs (bottom panel) isolated by crawl-out from whole skin explants of Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line), and ricΔ/Δ (green line) mice. Bar graphs represent the MFI ± SEM of N = 2 mice per group. One representative of 2 independent experiments with similar results is shown.

The proportion of mDCs in sLNs of day 12 rapΔ/Δ mice is elevated. FACS analysis of epidermis (A), dermis (B), and sLNs (C-D) of day 12 rapfl/fl and rapΔ/Δ littermates. Cells are gated on CD45+ (A), CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ (B), lymphocytes (C), or MHC-IIhigh CD11cint mDC (D). Numbers and bar graphs indicate mean frequency ± SEM of cells in the respective gate or quadrant (N = 5 mice for rapfl/fl and N = 3 mice for rapΔ/Δ).

The proportion of mDCs in sLNs of day 12 rapΔ/Δ mice is elevated. FACS analysis of epidermis (A), dermis (B), and sLNs (C-D) of day 12 rapfl/fl and rapΔ/Δ littermates. Cells are gated on CD45+ (A), CD45+ MHC-II+ CD11c+ (B), lymphocytes (C), or MHC-IIhigh CD11cint mDC (D). Numbers and bar graphs indicate mean frequency ± SEM of cells in the respective gate or quadrant (N = 5 mice for rapfl/fl and N = 3 mice for rapΔ/Δ).

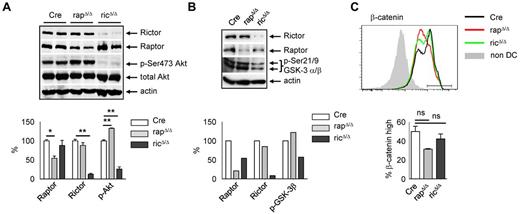

Raptor and Rictor differentially regulate Akt and GSK-3 phosphorylation

The signals triggering steady-state LC migration and the contribution of mTOR complexes to this process are incompletely understood. LC emigration from the skin is accompanied by maturation of the cells and a down-regulation of E-cadherin. The E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling pathway has been implicated in adhesion, migration, and the tolerogenic maturation of DCs.34 Because the expression of β-catenin and E-cadherin is reduced in rapΔ/Δ LCs, we analyzed the upstream components involved in the regulation of β-catenin stability, Akt, and GSK3α/β. mTORC2 is the predominant kinase phosphorylating Akt within its hydrophobic motif at Ser473.13 Depending on cell type and stimulus, at least 1 other kinase, DNA-PK, can phosphorylate Akt at Ser473.35 Moreover, mTORC1 negatively regulates mTORC2 via S6K1-mediated phosphorylation of Rictor at Thr1135 indicating that blocking mTORC1 function may augment Akt Ser473 phosphorylation.36 To examine whether Akt Ser473 phosphorylation is affected in rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ DCs, we performed Western blot analyses. Because the number of LCs is extremely low in rapΔ/Δ mice we used bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) generated in medium containing GM-CSF. Compared with resting splenic DCs in which Akt Ser473 phosphorylation is virtually absent (data not shown), we found a robust Akt Ser473 phosphorylation in Cre BMDCs at day 12 of the culture (Figure 7A). As expected Akt Ser473 phosphorylation is almost completely blocked in ricΔ/Δ but slightly elevated in rapΔ/Δ BMDCs (Figure 7A). GSK3α/β is an important downstream target of Akt, which becomes inactivated by its Akt-mediated phosphorylation at Ser21 (GSK3α) and Ser9 (GSK3β). Whether Akt-mediated inactivation of GSK3 is influenced by Akt Ser473 phosphorylation is currently unclear.35 As shown in Figure 7B, ricΔ/Δ BMDCs, which have a reduced Akt Ser473 phosphorylation (Figure 7A), also show a decreased GSK3α/β Ser21/9 phosphorylation, whereas rapΔ/Δ BMDCs with increased Akt Ser473 phosphorylation (Figure 7A), also show a slightly enhanced GSK3α/β phosphorylation. Ser9 phosphorylation-mediated inhibition of GSK3β results in a stabilization of β-catenin.37 FACS analyses of β-catenin expression in steady-state BMDCs revealed a weak but not significant reduction of β-catenin in ricΔ/Δ and despite the elevated Ser9 phosphorylation of GSK3β a stronger reduction in rapΔ/Δ BMDCs (Figure 7C), a finding that was even more pronounced in skin LCs (Figure 2B). The decreased level of β-catenin in rapΔ/Δ BMDCs and LCs potentially results from a lower expression of the protein, or other regulatory mechanisms rather than a decreased stabilization via GSK3β in the steady-state.

Raptor and Rictor deficiency differentially affect Akt and GSK-3 phosphorylation. (A-B) Total lysates of day 12 or day 13 Cre, rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ BMDCs isolated using CD11c magnetic bead separation were subjected to Western blot analysis of Rictor, Raptor and p-Ser473-Akt (A) or p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β (B) expression. Equal protein loading was confirmed by detection of actin. Bar graphs represent quantification of Raptor, Rictor, and p-Ser473-Akt (A) or p-Ser9 GSK3β (B). Expression of Raptor, Rictor, p-Ser473-Akt, and p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β was normalized to actin and set to 100% in Cre. (A) Raptor in rapΔ/Δ: 54.20 ± 5.68, P = .0195; Rictor in ricΔ/Δ: 12.62 ± 2.25, P = .0027; p-Ser473-Akt in rapΔ/Δ: 132.6 ± 0.96, P = .0084, p-Ser473-Akt in ricΔ/Δ: 25.98 ± 5.66, P = .0073; mean ± SEM of N = 2 mice per group. Data are from one of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (B) Raptor in rapΔ/Δ: 21.15; Rictor in ricΔ/Δ: 8.57; p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β in rapΔ/Δ: 122.18, p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β in ricΔ/Δ: 57.32. Data shown are single values from 1 of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (C) FACS analysis of β-catenin expression in day 10 Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line), and ricΔ/Δ (green line) BMDCs gated on CD11c+ MHC-II+. Bar graph represents mean frequency ± SEM of N = 2 mice per group of β-cateninhigh DCs gated as shown in the histogram. One of 2 independent experiments with similar results is shown.

Raptor and Rictor deficiency differentially affect Akt and GSK-3 phosphorylation. (A-B) Total lysates of day 12 or day 13 Cre, rapΔ/Δ and ricΔ/Δ BMDCs isolated using CD11c magnetic bead separation were subjected to Western blot analysis of Rictor, Raptor and p-Ser473-Akt (A) or p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β (B) expression. Equal protein loading was confirmed by detection of actin. Bar graphs represent quantification of Raptor, Rictor, and p-Ser473-Akt (A) or p-Ser9 GSK3β (B). Expression of Raptor, Rictor, p-Ser473-Akt, and p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β was normalized to actin and set to 100% in Cre. (A) Raptor in rapΔ/Δ: 54.20 ± 5.68, P = .0195; Rictor in ricΔ/Δ: 12.62 ± 2.25, P = .0027; p-Ser473-Akt in rapΔ/Δ: 132.6 ± 0.96, P = .0084, p-Ser473-Akt in ricΔ/Δ: 25.98 ± 5.66, P = .0073; mean ± SEM of N = 2 mice per group. Data are from one of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (B) Raptor in rapΔ/Δ: 21.15; Rictor in ricΔ/Δ: 8.57; p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β in rapΔ/Δ: 122.18, p-Ser21/9 GSK3α/β in ricΔ/Δ: 57.32. Data shown are single values from 1 of 2 independent experiments with similar results. (C) FACS analysis of β-catenin expression in day 10 Cre (black line), rapΔ/Δ (red line), and ricΔ/Δ (green line) BMDCs gated on CD11c+ MHC-II+. Bar graph represents mean frequency ± SEM of N = 2 mice per group of β-cateninhigh DCs gated as shown in the histogram. One of 2 independent experiments with similar results is shown.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that specific ablation of mTORC1 function by deletion of Raptor in CD11c+ cells leads to a lack of epidermal LCs in adult mice. In contrast, disruption of mTORC2 function by deletion of Rictor did not affect the homeostasis of LCs in the epidermis. We observed that Raptor-deficient LCs disappear from the epidermis over time: the abundance of epidermal LCs in very young mice (day 8) is equal to control littermates, whereas it is reduced to approximately 50% in day 14 rapΔ/Δ mice.

Mechanistically the loss of LCs might occur by increased cell death, a slower proliferation or an enhanced emigration of the cells or a combination of these processes. We found the tendency for a higher frequency of apoptosis in LCs but also an elevated proportion of recently divided LCs in rapΔ/Δ mice. mTOR is involved in the regulation of cell-cycle progression and rapamycin treatment results in a cell-cycle arrest in the G1 phase.31 Therefore, the findings that first the postnatal proliferative burst of LCs is not affected by the deletion of Raptor and second that the few LCs in the epidermis of rapΔ/Δ mice show an even enhanced proliferation, is unexpected. The postnatal proliferation of LCs might be unaffected in rapΔ/Δ mice because the LCs only recently gained CD11c expression and might therefore have only incompletely lost Raptor expression. The higher proportion of recently divided LCs in the epidermis of adult rapΔ/Δ mice may be a consequence of the few LCs “trying” to repopulate the empty epidermis. Although rapamycin treatment typically elicits cytostatic rather than cytotoxic effects, under certain conditions and in certain cell types, such as human monocyte derived DCs exposed to GM-CSF, it can induce apoptosis.26 Whether increased apoptosis of epidermal LCs in rapΔ/Δ mice actually accounts for the progressive loss of LCs is unclear. In vivo analysis of apoptotic cells is hampered by their quick removal from tissues and usually results in underrepresentation of the actual apoptosis rates. A good example is the thymus, where although more than 95% of all thymocytes undergo apoptosis, only additional artificial induction of apoptosis results in a more representative in situ detection of apoptotic cells.38 Analysis of dead cells in our own study did not reveal significant differences between LCs of knockout and control littermates in the epidermis (data not shown). As LCs have a very slow turnover and are relatively rare cells, it was not possible to measure weakly increased apoptosis rates here.

Crawl-out assays from the skin of young mice and the elevated proportion of mDCs found in the sLNs of young mice indicate that Raptor-deficient LCs have an increased tendency to leave the skin. It has been shown that rapamycin augments DC migration toward CCL19 in vitro and to LNs in vivo by promoting CCR7 expression.33 We could confirm these results by crawl-out assays from the skin into medium containing rapamycin. We obtained increasing frequencies of DCs and a gain of CCR7 expression by DCs with increasing concentrations of rapamycin. Raptor-deficient LCs, however, show a lower expression of CCR7 compared with control animals. This finding might be because of long-term effects of mTORC1 inhibition compared with acute rapamycin treatment, potentially because of mTORC1 functioning in the regulation of translation. The lowered expression of CCR7 however does not affect LC migration to the sLNs as observed in young mice.

Continuous LC migration under steady-state conditions contributes to the maintenance of peripheral tolerance but the sterile signals triggering spontaneous LC migration are not well understood. It has been shown that TGF-β and its receptor are critical for both development and homeostasis of LCs39-41 and mTOR is required for the translational regulation of TGF-β production by DCs.42 Whether mTOR-mediated translational control of TGF-β expression also plays a role in LC homeostasis needs to be clarified. TGF-β signaling is moreover indispensable to keep the epidermal LCs in an immature state41 and because Raptor-deficient LCs do not show an enhanced spontaneous maturation, there is apparently no defect in TGF-β expression or signaling.

We found a lower expression of Langerin, E-cadherin, and β-catenin in Raptor-deficient LCs. Down-regulation of E-cadherin seems to be a prerequisite for the emigration of LCs from the epidermis43 and the lowered expression of E-cadherin might therefore favor LC emigration in rapΔ/Δ mice. E-cadherin forms a complex with β-catenin, which acts additionally as a transcriptional cofactor in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.44 The dysregulated level of β-catenin might as well influence the migratory potential of LCs in rapΔ/Δ mice, because the E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling pathway was implicated in LC migration and the tolerogenic maturation of DCs under steady-state conditions.34 Furthermore β-catenin signaling is required for the production of immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β by intestinal lamina propria derived DCs.45 The level of free cytosolic β-catenin is tightly controlled by a posttranslational mechanism. Wnt as well as TLR signals lead to an inhibition of GSK3β resulting in accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin. Therefore, the lower expression of β-catenin in rapΔ/Δ LCs could be because of a failure of GSK3β inactivation or a weaker transcription/translation of β-catenin.

Stimulation of immature BMDCs with LPS induces GSK3β Ser9 phosphorylation and both steady-state and LPS-induced GSK3β Ser9 phosphorylation is reduced in rapamycin treated BMDCs.46,47 We found GSK3β Ser9 phosphorylation reduced in ricΔ/Δ but not in rapΔ/Δ BM-DC. We propose that the effect of rapamycin on GSK-3 Ser9 phosphorylation is because of the simultaneous inhibition of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 function. mTORC1 signaling inhibits GSK3 via an S6K1-mediated phosphorylation.48 Thus, inhibition of mTORC1 should result in a failure of GSK3 inhibition, but only if the Akt-mediated phosphorylation of GSK3 is blocked as well. We propose that the enhanced mTORC2 activity in rapΔ/Δ BMDCs, which results in enhanced Akt Ser743 phosphorylation and thereby probably in an enhanced activity of Akt, restores the defect of mTORC1-mediated GSK3 phosphorylation/inactivation and Akt takes over this function. Ser473 phosphorylation was recognized to be essential only for Foxo1/3A but not for GSK3 or TSC2 phosphorylation by Akt. Nevertheless, Ser473 phosphorylation is known to enhance Akt activity. Recently it was shown that under certain conditions phosphorylation of GSK3 downstream of Akt actually is dependent on Ser473 phosphorylation of Akt.49 Therefore, the reduced Akt Ser473 phosphorylation in ricΔ/Δ BM-DC may account for reduced GSK3α/β phosphorylation. The reduced levels of β-catenin in rapΔ/Δ BMDCs seems to be because of a transcriptional and/or translational dysregulation of β-catenin expression rather than a decreased stabilization of the protein. Whether this mechanism holds true for steady-state LCs in vivo needs to be confirmed. The hypothesis that E-cadherin and β-catenin expression influence the homeostasis of LCs in the epidermis is yet uncertain because the LC network is intact and indistinguishable from wild-type animals in mice with LC/DC-specific expression of constitutively active β-catenin or LC/DC-specific deficiency of β-catenin or E-cadherin.50

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Bol, W. Mertl, S. Heinzl, and M. Grdic for excellent animal care. The authors thank Markus Ruegg from the University of Basel for the Raptorfl/fl and Rictorfl/fl mice.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 914/A06.

Authorship

Contribution: B.K. performed research and analyzed data; and T.B. designed the research wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: The authors declare no competing financial intersts.

Correspondence: Thomas Brocker, Institute for Immunology, LMU Munich, Goethestrasse 31, 80336 Munich, Germany; e-mail: tbrocker@med.uni-muenchen.de.