In this issue of Blood, Haroche and colleagues report significant therapeutic activity of the BRAF inhibitor, vemurafenib, in 3 patients with rare histiocytic conditions, Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1

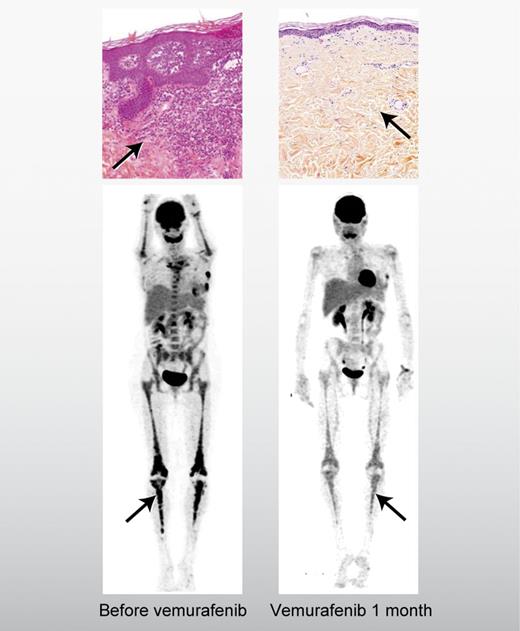

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) is the epitome of orphan diseases. The Erdheim-Chester Global Alliance estimates that fewer than 500 cases have been reported in the medical literature since it was first described as a discrete clinical entity in 1930. Although more cases of ECD have been reported in the past decade, diagnosis is challenging because the main pathologic feature of “foamy”-appearing lipid-laden macrophages (histiocytes) can be seen in many other conditions, so identification of ECD rests on the coordinated incorporation of other clinical data, including infiltration of the histiocytes in the retroperitoneum and the curious, near-universal finding of bilateral sclerotic changes in the long bones, most vividly seen on 99Technetium or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose imaging (see figure).2 Although ECD can be indolent in some patients, in others it can progress inexorably and fatally, often resulting in fibrosis in the heart and the arteries.

Saving orphans: BRAF targeting of histiocytosis. A patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the skin (top panels) and Erdheim-Chester disease in the long bones (bottom panels) before and after treatment with vemurafenib.1 Professional illustration by Alice Y. Chen.

Saving orphans: BRAF targeting of histiocytosis. A patient with Langerhans cell histiocytosis in the skin (top panels) and Erdheim-Chester disease in the long bones (bottom panels) before and after treatment with vemurafenib.1 Professional illustration by Alice Y. Chen.

Another rare disease, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), is considered histologically distinct from ECD.1 LCH most commonly affects children, frequently presenting as lytic bone lesions or infiltrative lesions of the skin, lungs, and anterior pituitary. LCH and ECD have a shared history of controversy regarding whether they are reactive, inflammatory conditions or clonal, neoplastic diseases.2,3 Recent studies, however, found that 57% of LCH cases and 54% of ECD patients harbored BRAF V600E mutation in the diseased tissue, strongly suggesting a neoplastic etiology in most cases.4,5

Haroche et al have tested the notion that the BRAF V600E acts as a so-called “driver mutation” of these diseases by treating 3 patients with refractory ECD, 2 of whom had coincident LCH, with vemurafenib, which was recently approved for use in patients with metastatic melanoma characterized by BRAF V600E mutation.1,6 The responses in ECD and LCH were, in the words of the authors, “dramatic.” Two of the 3 patients had symptomatic improvement within days of the initiation of vemurafenib and all 3 patients had significant disease regression after a few weeks of treatment. In the 2 patients who had both LCH and ECD, there was clinical response in both histiocytic conditions. It should be noted that vemurafenib was not without toxicity and all 3 patients required a reduction from the initial dose due to rash, a common side-effect. Further, the dramatic nature of the results must be tempered against the small size of the case series and the short follow up. Median progression-free survival in patients with vemurafenib-treated melanoma was less than 6 months, so the duration of response in the histiocytosis patients will continue to be a point of interest.6

As a corollary to this study, 2 of the 3 patients reported had both ECD and LCH. A few case reports have suggested coincidence of what are considered separate histiocytic entities.7,8 The finding here that both patients had the same BRAF mutation in both histiocytoses with similar therapeutic responses to vemurafenib strongly suggests, by the law of parsimony, a possible developmental link between ECD and LCH. As evidence mounts that most cases of LCH are clonal and neoplastic, and that the cell of origin is most likely an immature myeloid dendritic cell rather than a mature tissue-based dendritic cell,3,9 the coincidence of the rare LCH with the ultra-rare ECD might prompt re-examination of the connection between these 2 conditions.

These results will surely come as welcome news to the devoted cadre of physicians who care for this collection of rare diseases as well as the patients who suffer from them. At present, the best-established treatment of ECD is interferon and standard therapies of LCH use cytotoxic agents.3,10 Thus, a targeted treatment approach not only adds a new element to the therapeutic armamentarium, but offers the possibility of less-toxic treatments; in the case series, vemurafenib at the ultimate treatment dose was quite well tolerated. Although the response duration remains unproven, there is also hope that ECD and LCH, which appear to be cytogenetically less complex than metastatic melanoma, might develop resistance at a lower rate and that BRAF inhibitors, whether vemurafenib or others, could result in long-term responses.

The identification of another pair of diagnoses that have therapeutic responses based on the discovery of a recurrent gene mutation with the potential to activate aberrant signaling coupled with the development of an effective inhibitor further validates a genetically based treatment paradigm in which treatment options are less driven by histology than by DNA sequence. This approach is fast becoming the law of the land in diseases such as lung cancer, and the results of Haroche et al suggest that the benefit of targeted therapies could expand even to the rarest of the rare diseases.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal