Abstract

Rarely in the field of cancer treatment did we experience as many surprises as with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Yet, the latest clinical trial reported by Lo-Coco et al in the New England Journal of Medicine is a practice-changing study, as it reports a very favorable outcome of virtually all enrolled low-intermediate risk patients with APL without any DNA-damaging chemotherapy. Although predicted from previous small pilot studies, these elegant and stringently controlled results open a new era in leukemia therapy.

Historical background

For the past 25 years, retinoic acid (RA) and arsenic trioxide (arsenic) were introduced in the daily management of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Historical aspects have been extensively reviewed elsewhere.1,2 Briefly, RA induces a dramatic response, leading to complete remissions, but most patients will eventually experience a relapse of their condition.3 Combination RA and anthracyclines definitively cure 70% of patients with APL,4 as does arsenic as a single agent.5,6 Optimization of the RA/chemotherapy combination later yielded higher cure rates. APL is driven by the promyelocytic leukemia-RA receptor-α (PML/RARA) oncogene,2 and biological studies have demonstrated that both drugs target the PML/RARA oncoprotein for proteasome-mediated degradation.7 Yet, it was unclear whether the 2 drugs should be combined in patients with APL. Therefore, in most countries, arsenic was used as a salvage therapy for patients whose disease had failed the standard RA/anthracycline regimen.8

On the basis of preclinical animal models (see below), the first trial combining RA and arsenic frontline in de novo patients was reported in 2004.9 Yet, the therapeutic scheme included a chemotherapy-based consolidation regimen given after the RA/arsenic induction. Patients who did not experience hemorrhage all underwent complete remissions, and time to complete remission was accelerated when compared with RA or arsenic alone. A 5-year survival plateau demonstrated definitive cures of virtually all patients.10 Two years later, the MD Anderson group reported that the frontline RA/arsenic combination would induce excellent disease control in more than 90% of standard-risk patients without hyperleukocytosis at presentation.11,12 Importantly, in this case, there was no systematic chemotherapy-based consolidation, only gemtuzumab ozogamicin in those patients in whom transient treatment-induced hyperleukocytosis developed. Several other studies have incorporated arsenic in various types of regimens with some chemotherapy.13-15 All of these studies led to visible pleas in favor of frontline RA/arsenic combinations without chemotherapy.16 Yet, an expert panel rightfully argued that any shift from the standard-of-care RA/anthracycline regimen to this novel RA/arsenic combination required large randomized clinical studies.8 One such large study is now reported in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and will likely pave the way for global practice changes.17

Biological basis

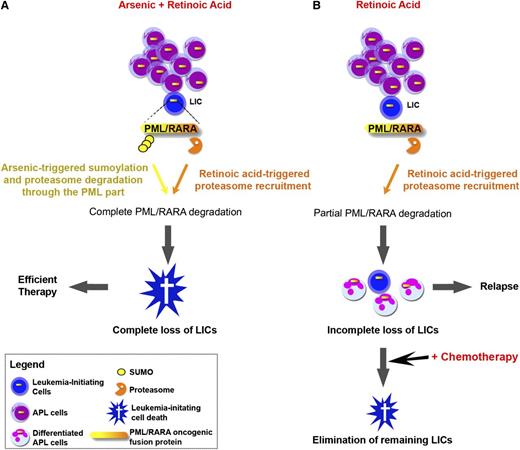

The basis for RA response in APL was believed to be differentiation.18 RA and arsenic antagonize for differentiation,19 initially precluding use of the combination of the 2 agents in patients with APL. Yet, when subsequent studies revisited this issue in mice models, a dramatic synergy for APL eradication was observed in all models tested.20-23 Subsequent mechanistic studies revealed that the extraordinary potency of the RA/arsenic combination relies on loss of leukemia-initiating activity, rather than differentiation.18,23 Several lines of evidence have linked the loss of leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) to therapy-induced degradation of the PML/RARA oncoprotein7,23,24 (Figure 1). Critically, because RA and arsenic target distinct moieties of the PML/RARA fusion and because the degradation pathways are noncross resistant,25-27 these agents were expected to be highly synergistic for the degradation of this oncoprotein, thus explaining greatly enhanced LIC clearance (Figure 1). Yet, note that the molecular and cellular basis for loss of APL cell clonogenic activity on PML/RARA loss still remains to be identified.

Schematic representation of RA and/or arsenic therapy in APL. (A) Complete PML/RARA degradation by the RA/arsenic combination abrogates self-renewal and clears LICs, yielding APL cure. (B) Incomplete PML/RARA degradation by RA (or arsenic) allows survival of some LICs, yielding APL relapses. These remaining LICs can be cleared by concomitant or subsequent chemotherapy.

Schematic representation of RA and/or arsenic therapy in APL. (A) Complete PML/RARA degradation by the RA/arsenic combination abrogates self-renewal and clears LICs, yielding APL cure. (B) Incomplete PML/RARA degradation by RA (or arsenic) allows survival of some LICs, yielding APL relapses. These remaining LICs can be cleared by concomitant or subsequent chemotherapy.

Clinical consequences and open questions

It is not so often that clinicians have the choice between 2 very different treatment strategies that are both curative. This trend raises new issues such as quality of life during therapy, delayed toxicities, and cost-effectiveness, which are relatively novel in the cancer field. First, the follow-up on survival duration in the NEJM study is still short, and it will be interesting to reanalyze the data in 2 to 3 years, together with reports from several ongoing trials with a similar design. In principle, one could think that cure in the absence of anthracyclines is preferable. Indeed, the toxicity profile during induction therapy primarily consisted of acute cytopenia with the resulting infections in the RA/anthracycline group, whereas liver toxicities and the Q-T syndrome were observed in patients treated with the RA/arsenic combination. In general, the NEJM study found the RA/arsenic combination to be better tolerated and to have a more acceptable toxicity profile, as could be expected. Yet, apart from rare acute toxicities, some issues were raised on potential long-term toxicities of arsenic, notably on skin cancer or vascular occlusions, well-known complications of long-term arsenic exposure.1 In that respect, a careful toxicity profiling after APL cure demonstrated that residual levels of arsenic were in the range of untreated control participants,10 although further studies with longer follow-up should be performed to unequivocally demonstrate the absence of long-term toxicity.

Other issues must be discussed, such as the cost of arsenic in many countries28 that has often led to restrictive indications by regulatory agencies. These issues may well impede, or at least retard, generalization of the frontline combination. In other countries, the mere availability of the drug is currently an issue. The existence of an oral form of arsenic, such as arsenic sulfide, which seems as potent as intravenous arsenic trioxide, could represent another revolution (Zhu Chen and Sai-Juan Chen, Shanghai Institute of Hematology, Ruijin Hospital, personal communication, June 2013).29,30 Indeed, arsenic sulfide, by allowing patients to take pills and to be treated as outpatients at least during the consolidation phase, should yield much better patient comfort.

Apart from some intriguing unresolved biological questions, 2 major clinical issues remain regarding APL therapy: (i) the unpredictable occurrence of bleeding and sudden death; and (ii) patients with leukocytosis at presentation who are at higher risk for differentiation syndrome and an unfavorable outcome.8,16 First, larger clinical series and in-depth analysis of preclinical models are required to determine whether the frontline RA/arsenic combination opposes the occurrence of life-threatening bleeding disorders. With respect to the second point, the available clinical studies of the frontline RA/arsenic combination were all performed in patients without leukocytosis at presentation, which usually represent 80% of de novo patients with APL. Future studies could examine whether patients with leukocytosis at presentation might also avoid chemotherapy. In particular, it will be important to determine whether the RA/arsenic combination increases or diminishes the incidence of differentiation syndrome. From animal models, one may expect that synergistic degradation of PML/RARA could blunt this severe complication by immediately abrogating self-renewal, but this remains to be explored. On the other hand, chemotherapy strongly opposes treatment-induced blast proliferation. In that respect, the NEJM study found a slightly higher incidence of treatment-induced leukocytosis with the RA/arsenic regimen, but this finding was not associated with worse outcomes. In fact, only 2 early deaths occurred in the study, both in the RA/chemotherapy group.17 Clearly, further studies, also assessing the impact of RA or arsenic doses, are required to clarify this point.

In conclusion, the perspective of curing leukemia with minimal toxicities, possibly using oral drug intake, opens a new era in cancer treatment. A few key features of the APL saga must be stressed: many of the hallmark findings were made by chance more than design2 ; progress relied primarily on the academic world; international cooperation was the key to success; and basic science accompanied (and sometimes even guided) clinical explorations, providing a spectacular illustration of the power of translational research. In these times of hyperregulation, let us hope that the APL miracle could occur again today and that other diseases will follow on the tracks to cure.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the laboratory for discussions.

The laboratory is supported by Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Medicale, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université Paris-Diderot, Institut Universitaire de France, Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut National du Cancer, Saint Louis Institute and the Paris Alliance of Cancer Research Institutes (A.N.R.); Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (Griffuel Award; H.d.T.); Canceropôle Ile de France; and the European Research Council (STEMAPL advanced grant; H.d.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: V.L.-B. and H.d.T. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hugues de Thé, UMR 7151, Hôpital St. Louis, 1 Avenue C, Vellefaux, Paris, 75475 France; email: dethe@paris7.jussieu.fr.