Key Points

BTLA-HVEM interaction negatively regulates the proliferation of LTγδ.

BTLA-HVEM interaction appears as a new possible mechanism of immune escape by lymphoma cells.

Abstract

Vγ9Vδ2 cells, the major γδ T-cell subset in human peripheral blood, represent a T-cell subset that displays reactivity against microbial agents and tumors. The biology of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells remains poorly understood. We show herein that the interaction between B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) and herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM) is a major regulator of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation control. BTLA was strongly expressed at the surface of resting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and inversely correlated with T-cell differentiation. BTLA-HVEM blockade by monoclonal antibodies resulted in the enhancement of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell receptor–mediated signaling, whereas BTLA-HVEM interaction led to a decrease in phosphoantigen-mediated proliferation by inducing a partial S-phase arrest. Our data also suggested that BTLA-HVEM might participate in the control of γδ T-cell differentiation. In addition, the proliferation of autologous γδ T cells after exposition to lymphoma cells was dramatically reduced through BTLA-HVEM interaction. These data suggest that HVEM interaction with BTLA may play a role in lymphomagenesis by interfering with Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation. Moreover, BTLA stimulation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells appears as a new possible mechanism of immune escape by lymphoma cells.

Introduction

Vγ9Vδ2 cells represent a major peripheral blood T-cell subset in humans displaying a broad reactivity against microbial agents and tumors. They have the ability to simultaneously recognize and respond to phosphorylated nonpeptide antigens (phosphoantigens, PAg),1 molecules found on a wide variety of pathogenic organisms, and tumor cells1-5 in a HLA-unrestricted fashion.6 Accordingly, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are involved in tumor-immune surveillance, notably against carcinomas7-11 and hematologic malignancies.12-15

Maintenance of lymphocyte population size is usually achieved by balancing the generation of new cells and clonal expansion with cell death. However, the homeostasis of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells remains poorly understood. The size of the Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell pool is regulated by the availability of interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7, and their homeostasis is maintained in competition with αβ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells.16 When both αβ and γδ cell types are adoptively transferred in equal numbers into T-cell receptor (TCR)β−/−/δ−/− mice, αβ T cells rapidly outgrow γδ T cells.16 Thus, γδ T cells have a substantial disadvantage compared with αβ T cells during their expansion. Molecular pathways regulating the proliferation and homeostasis of γδ T cells are still not known. By comparison, it is well-accepted that co-receptors positively or negatively regulate αβ T-cell activation, expansion, and survival. Among these co-receptors, molecules of the CD28:B7 family have a potent regulatory effect on TCR-mediated activation. Some of these co-receptors like PD-1 are also able to modulate Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation.17 B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), a recently described member of the CD28:B7 family structurally related to CTLA-4 and PD-1, is expressed by most lymphocytes.18 Its ligand, herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), is a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily expressed by T, B, and NK cells; dendritic cells; and myeloid cells.19

BTLA-deficient mice exhibit normal B- and T-cell development.20 However, mature lymphocytes from these mice display higher frequencies of memory T cells and generate more memorylike responses.20 Moreover, BTLA-deficient mice21,22 and in vitro observations obtained using agonist anti-BTLA antibodies and HVEM-Ig fusion proteins23-25 have evidenced BTLA as a negative modulator of immune responses against self- and allo-antigens and antigen-independent homeostatic expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.22 Dysfunction of the BTLA-HVEM pathway is suspected to play a role in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune and neoplastic diseases,26-29 especially in the dysfunction of innate immunity in inflammatory diseases.30 Very little functional data about BTLA are available for humans. Cross-linking of BTLA with an agonistic mAb can inhibit αβ T-cell proliferation and the production of interferon-γ and IL-10 in response to anti-CD3 stimulation.31 Moreover, BTLA stimulation inhibits the function of both human melanoma-specific and cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific T cells.26,32 Among hematologic malignancies, we have previously shown that BTLA is expressed by neoplastic cells in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but not in most B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL), although various reactive immune cells of the lymphoma microenvironment are BTLA-positive.33 The BTLA ligand, HVEM, displays frequent abnormalities in human B-cell malignancies,33,34 especially in follicular lymphoma (FL), and they harbor a high frequency of mutations in the TNFRSF14 (HVEM) gene. These mutations typically lead to the truncation of TNFRSF14 and are accompanied by the deletion of the wild-type allele, which suggests a possible role for HVEM as a tumor-suppressor gene.35,36

In this study, we show that BTLA expression is regulated not only during Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell differentiation but also upon TCR-mediated activation. BTLA blockade improves TCR signaling. Furthermore, we demonstrate that its interaction with HVEM negatively regulates TCR-independent and TCR-dependent Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation, and that HVEM-positive FL cells efficiently inhibited Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation.

Material and methods

Patients

Eleven lymph nodes from lymphoma patients were evaluated including 9 NHLs and 3 Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). NHL samples were classified as B-cell FL (n = 7) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL, n = 1). HL samples belonged to the classical form. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Institut Paoli Calmettes. The control group consisted of 7 healthy volunteers (HV) provided by Marseille Blood Bank. Mononuclear cells from lymph nodes were isolated after mechanical disruption. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HV were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep, Abcys). Isolated cells were viably frozen in fetal bovine serum (PAN Biotech) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich) until use.

Reagents and antibodies

Bromohydrin pyrophosphate (BrHPP) was obtained from Innate Pharma (Marseille, France) with recombinant human IL2 (rIL2) purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and Fc protein used for functional experiments and immunofluorescence analysis are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Generation of anti-human HVEM, BTLA, and PD-1 mAbs

Characterization of new HVEM-specific mAbs (HVEM-11.8 and 18.10)

Stable LTK-HVEM (2 × 105 cells) transfectants were treated with a mixture of 10 µg/mL of BTLA-Fc and a range of concentrations (0.001-30 µg/mL) of HVEM-11.8 or 18.10 mAb for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with R-PE–conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-human IgG (H+L) (Immunotech) for 30 minutes at 4°C. To measure the inhibition activity, the PD1-3 mAb was included in the same conditions as the nonblocking control. Binding of HVEM-Fc and blocking activity of either HVEM-11.8 or 18.10 mAb were determined by flow cytometry on a BD FACScan cytometer. For the HVEM-Fc protein, extracellular domain (Met1-Val202) of HVEM fused to the Fc protein of human IgG1 was cloned into the expression vector Cos Fc Link (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals). For HVEM ΔCRD1-Fc protein, extracellular domain deleted from its CRD1 domain fused to the Fc protein of human IgG1 was cloned into the expression vector Cos Fc Link (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals). For HVEM V74A-Fc protein, Val74 was mutated into alanine.

Cell culture

Effector-γδ T cells were established and maintained as previously described.15 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stimulated with BrHPP (3 µM) and rIL2 (100 IU/mL). rIL-2 was renewed every 2 days and cells were maintained at 1.5 × 106 cells/mL. The FL cell lines RL and Karpas-422 were cultured (0.5.106 /mL) in complete RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum.

Flow cytometry

2.105 PBMCs were washed in PBS (Cambrex Bio Science) and incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes with the specified mAb conjugates. After incubation and washing, samples were analyzed on a LSRFortessa (Becton Dickinson) using DIVA software (BD Bioscience, Mountain View, CA). For analysis of CD107a expression, γδ T lymphocytes were incubated at 37°C in the presence of anti-CD107a and anti-Cd107b conjugate and golgi stop with or without BrHPP and anti-BTLA 8,2. After 4 hours, cells were collected washed in 0.5M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and analyzed in flow cytometry.

Proliferation assay

Purified γδ cells were labeled with 2.5 µM carboxyfluoroscein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes, LifeTech) for 10 minutes at 37°C or with CellTrace Violet (Molecular Probes, LifeTech) for 10 minutes at 37°C. 2.105 CellTrace- or CFSE-labeled cells were cultured in 96-well plates with or without indicated mAb or increasing doses of BrHPP. When specified, after 2 days of culture, supernatants were collected and TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed. After 5 days of culture in the presence of 200 U/mL IL-2, CellTrace or CFSE dilution was evaluated by flow cytometry.

TNF-α release assay

Purified γδ T cells were stimulated with 50 nM BrHPP and 200 UI/mL IL-2 for 48 hours. Supernatants were collected and stored until use. Measurement of secreted TNF-α was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer (RnDSystems).

Cell-cycle analysis

After 3 and 4 days in culture with IL-2 + BrHPP, purified γδ T cells were cultured with 15 µM BrdU for 1 hour and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained for BrdU and 7-AAD according to the manufacturer’s instruction (FITC BrdU Flow Kit, BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometry analysis of cell-incorporated BrdU (with FITC anti-BrdU) and total DNA content (with 7-AAD) in purified γδ T cells allowed for the discrimination of cell subsets that were apoptotic (7-AADneg), or in G0/G1 (BrDU+, 4-AADlow), S (BrDU+), or G2/M (BrDUneg, 7AADbright) phases of the cell cycle.

Chromium release assay

106 target cells (RL or Daudi) were incubated with 20 µCi 51Cr (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 1 hour and mixed with effector cells in 150 µL RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum. After 4 hours of incubation at 37°C, 50 µL supernatant of each sample was transferred in LUMA plates, and radioactivity was determined by a γ counter. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated using the standard formula [(experimental – spontaneous release / total – spontaneous release) × 100] and expressed as the mean of triplicate.

Immunofluorescence

180 000 resting or 1h-BrHPP (1 µM) preactivated Vγ9ςδ2 T cells were incubated for 30 minutes, in the presence or absence of HVEM+ cells (ratio 1:1), on poly-l-lysine pretreated coverslips. Cells were then fixed in methanol at −20°C for 6 minutes and washed in PBS. After blocking in PBS 10% stromal vascular fraction, cells were incubated with primary antibodies: TCRVδ2 mAb (mouse IgG1, 10 μg/mL) and BTLA (mouse IgG2b, 10 μg/mL) mAb for 1 hour. After washing in PBS, 0.1% Tween20, BTLA staining was detected using a specific anti-IgG2b secondary antibody conjugated to cyanine 5 (Cy5) from Jackson Laboratories. DNA was stained with 250 ng/mL DAPI (Roche Diagnostics) during secondary staining. Cells were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and examined on a LSM-510 Carl Zeiss confocal microscope with a ×63 NA1.4 Plan Apochromat objective. Five images of cell conjugates were taken among the cell conjugates observed.

Western blot analysis

1.106 γδ T cells were treated for 5 minutes with low-dose BrHPP in RPMI medium with 10% serum. Cells were then placed on ice, washed in PBS, and lysed in 20 µL of ice-cold HNTG buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM EGTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, and 1.5 mM MgCl2) in the presence of protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science) and 100 µM Na3VO4. Protein quantification in all cell lysates was performed according to the manufacturer (Biorad quantification kit). Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis 10%, followed by Western blotting. Primary antibodies used were from cell signaling: rabbit anti–phospho-Zap70 antibody, rabbit anti–phospho-Erk1/2 antibody, rabbit anti-ERK1/2 and rabbit anti-ZAP70 (all from Cell Signaling Technologies). Primary antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Laboratory). Immunoreactive bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescent reagents (Pierce). Quantification of signals was performed using ImageJ software, and the signal of phosphorylation was normalized with that of the corresponding total protein.

Statistics

Results are expressed as median ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Wilcoxon test and Mann-Whitney t test. P values < .05 were considered significant. The GraphPad Prism statistical analysis program was used.

Results

BTLA expression is inversely correlated with Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell differentiation

We first set to determine the expression of BTLA in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells by performing ex vivo multicolor flow cytometry analysis on PBMCs from HV. BTLA was strongly expressed at the surface of resting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (52.5% ± 5; Figure 1A), unlike PD-1 which was expressed at the minimal level as previously shown17 and other co-signaling molecules such as CTLA-4 and inducible cosimulator, which were absent. As previously reported,32 BTLA was also expressed on CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells and on B cells (Figure 1B).

BTLA expression on resting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from HV. (A) Multiparametric flow cytometry analysis of B7/CD28 family members’ expression on peripheral γδ T cells (CD3+TCRVγ9+) gated from HV PBMC (n = 8). (B) Expression of BTLA on CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells and B cells (n = 4). (C) Gating strategy for BTLA expression on γδ T cells’ differentiation subsets by flow cytometry. γδ T cells were analyzed for CD45RA and CD27 expression, resulting in the following subsets of γδ T lymphocytes: naïve (CD45RA+CD27+), CM (CD45RA−CD27+), EM (CD45RA−CD27−), and TEMRA (CD45RA+CD27−). (D) Representative histograms of BTLA expression in γδ T-cell differentiation subsets. γδ T cells from PBMCs of HV (n = 4) were analyzed by flow cytometry for BTLA expression according to differentiation subsets. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

BTLA expression on resting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from HV. (A) Multiparametric flow cytometry analysis of B7/CD28 family members’ expression on peripheral γδ T cells (CD3+TCRVγ9+) gated from HV PBMC (n = 8). (B) Expression of BTLA on CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T cells and B cells (n = 4). (C) Gating strategy for BTLA expression on γδ T cells’ differentiation subsets by flow cytometry. γδ T cells were analyzed for CD45RA and CD27 expression, resulting in the following subsets of γδ T lymphocytes: naïve (CD45RA+CD27+), CM (CD45RA−CD27+), EM (CD45RA−CD27−), and TEMRA (CD45RA+CD27−). (D) Representative histograms of BTLA expression in γδ T-cell differentiation subsets. γδ T cells from PBMCs of HV (n = 4) were analyzed by flow cytometry for BTLA expression according to differentiation subsets. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

We next verified whether BTLA expression varied depending on the developmental status of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells defined by CD45RA and CD27 expression38 (Figure 1C-D). BTLA was primarily expressed on naïve (N; CD45RA+CD27+) and central memory (CM) T cells (CD45RA−CD27+), and to a lesser extent on effector memory (EM) T cells (CD45RA−CD27−) (Figure 1C-D). Thus, in line with data obtained on CD8+ αβ T cells,26,32 BTLA is found on naïve T cells and is progressively downregulated in memory and differentiated effector-type cells, As a comparison, we studied the expression of PD-1 in the various γδ T-cell subsets. PD-1was present on all subsets with preferential expression on EM population (TemH1; CD45RA–CD27–) (supplemental Figure 1).32

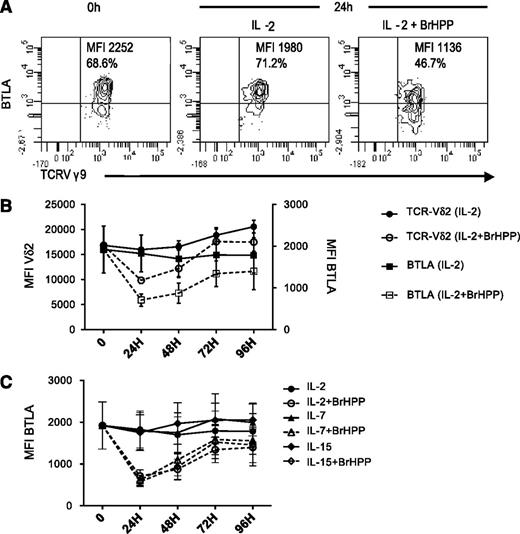

BTLA and TCR are concurrently downregulated during activation

We next determined whether BTLA expression was regulated during Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell activation. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were stimulated with IL-2 alone or in combination with the synthetic PAg BrHPP and monitored over a period of 5 days. The intensity of BTLA expression was constant in IL-2–treated cells, whereas expression significantly decreased within 24 hours after IL-2+BrHPP stimulation (P = .002; Figure 2A) and returned to baseline at 72 hours (Figure 2B). We found a concurrent downregulation of BTLA and TCR induced by BrHPP (Figure 2B), but not with IL-2 alone; consistent with previous studies on αβ T cells,39-41 PD-1 expression was significantly upregulated at 24 hours under BrHPP stimulation (supplemental Figure 2). Other cytokines, signaling through the common γ-chain, are known to activate γδ T cells. Similarly to IL-2, BrHPP, added to IL-7 or IL-15, induced the downregulation of BTLA and the TCR on Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Figure 2C). Of note, these cytokines induced significant γδ T-cell proliferation (data not shown).

BTLA downregulation during activation course of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (A) Gating strategy showing a representative expression profile of BTLA expression before and after 24 hours in culture with 200 UI/mL IL-2±BrHPP (1 μM). (B) Kinetic analysis of the intensity of BTLA expression (squares, n = 10) and TCR expression (circles, n = 7) after stimulation by IL-2 alone (closed symbols) or in combination with 1 μM BrHPP. (C) Kinetic analysis of BTLA after stimulation by IL-2 (circles, 200 UI/mL), IL-7 (triangles, 25 ng/mL), or IL-15 (diamonds, 10 ng/mL) in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of BrHPP (1 μM) (n = 3). Data represent mean ± SEM of BTLA or TCR Vδ2 MFI.

BTLA downregulation during activation course of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (A) Gating strategy showing a representative expression profile of BTLA expression before and after 24 hours in culture with 200 UI/mL IL-2±BrHPP (1 μM). (B) Kinetic analysis of the intensity of BTLA expression (squares, n = 10) and TCR expression (circles, n = 7) after stimulation by IL-2 alone (closed symbols) or in combination with 1 μM BrHPP. (C) Kinetic analysis of BTLA after stimulation by IL-2 (circles, 200 UI/mL), IL-7 (triangles, 25 ng/mL), or IL-15 (diamonds, 10 ng/mL) in the presence (open symbols) or absence (closed symbols) of BrHPP (1 μM) (n = 3). Data represent mean ± SEM of BTLA or TCR Vδ2 MFI.

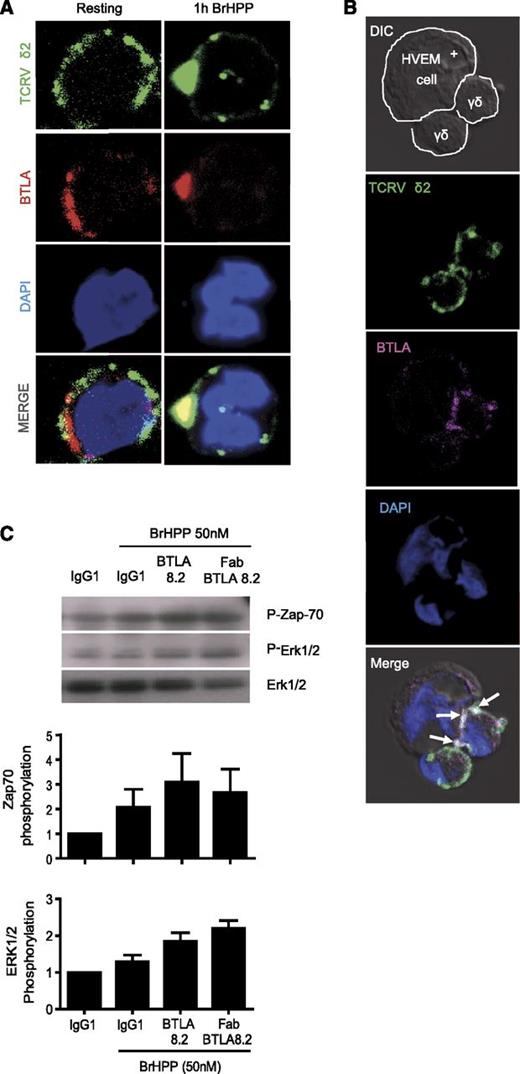

Upon activation, BTLA is clustered close to the TCR and reduces TCR-mediated signaling

The observation of correlated regulation of TCR and BTLA expression at the surface of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells strongly suggested a potential physical relationship. Consequently, we next investigated the subcellular localization of BTLA upon TCR-mediated activation. We first activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with PAg and followed the TCR and BTLA localization by confocal microscopy. As expected, BTLA was localized close to the TCR (Figure 3A). This applies even after polarization induced by a HVEM+ lymphoma cell line. We observed a clustering of BTLA and the TCR at the synapse between Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and target cells (Figure 3B, arrows). Of note, staining of BTLA differed between Vγ9Vδ2 T cells because we used a bulk population of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells that includes all differentiation stages with different levels of BTLA expression (Figure 1A). The close localization of the TCR and BTLA suggested that BTLA engagement could affect TCR-dependent signaling. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were then stimulated via the TCR, using PAg stimulation, in the presence or absence of an anti-BTLA blocking antibody. As observed in Figure 3C, phosphorylation of ZAP-70 and Erk1/2 was increased after BTLA blockade. These data suggest that BTLA negatively regulates TCR-mediated activation.

BTLA co-clustered with Vγ9Vδ2TCR after activation. (A) Distribution of BTLA and Vδ2TCR on resting (left panel) or BrHPP-activated γδ T cells (right panel). Cells were first fixed and permeabilized, and then stained with anti-BTLA (clone 7.1, IgG2b, red) and anti–TCRVδ2-FITC (IgG1, green) mAbs. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). The second antibody used anti-mouse IgG2b-Cy5 for BTLA detection. Images were analyzed on a confocal microscope. Yellow indicates the overlay of red and green signals. Shown are representative images from 4 independent experiments. (B) Distribution of BTLA and Vδ2TCR on polarizing cells after interaction with HVEM-positive lymphoma cells (RL cells). Cells were first fixed and permeabilized and then stained with anti-BTLA 7.1 (pink) and anti–TCRVδ2-FITC (green) mAbs. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). The second antibody used anti-mouse IgG2b-Cy5 for BTLA detection. Images were analyzed on a confocal microscope. The white arrows pointing to the white shading indicate the overlay of pink and green signals. (C) BTLA blockade (with full-length BTLA 8.2 or its Fab form) increases the phosphorylation of Zap-70 and Erk1/2. 1 × 106 purified γδ T cells derived from a HV were stimulated for 5 minutes with BrHPP (50 nM) and isotype control or anti–PD-1.3.1 mAb or anti-BTLA 8.2. Total cellular proteins were separated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and revealed by Western blot analysis using a phospho-Zap-70 or phospho-Erk1/2 antibody. Quantification of phosphorylation was calculated as the ratio between the signals of phospho-protein and the corresponding total protein.

BTLA co-clustered with Vγ9Vδ2TCR after activation. (A) Distribution of BTLA and Vδ2TCR on resting (left panel) or BrHPP-activated γδ T cells (right panel). Cells were first fixed and permeabilized, and then stained with anti-BTLA (clone 7.1, IgG2b, red) and anti–TCRVδ2-FITC (IgG1, green) mAbs. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). The second antibody used anti-mouse IgG2b-Cy5 for BTLA detection. Images were analyzed on a confocal microscope. Yellow indicates the overlay of red and green signals. Shown are representative images from 4 independent experiments. (B) Distribution of BTLA and Vδ2TCR on polarizing cells after interaction with HVEM-positive lymphoma cells (RL cells). Cells were first fixed and permeabilized and then stained with anti-BTLA 7.1 (pink) and anti–TCRVδ2-FITC (green) mAbs. The nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). The second antibody used anti-mouse IgG2b-Cy5 for BTLA detection. Images were analyzed on a confocal microscope. The white arrows pointing to the white shading indicate the overlay of pink and green signals. (C) BTLA blockade (with full-length BTLA 8.2 or its Fab form) increases the phosphorylation of Zap-70 and Erk1/2. 1 × 106 purified γδ T cells derived from a HV were stimulated for 5 minutes with BrHPP (50 nM) and isotype control or anti–PD-1.3.1 mAb or anti-BTLA 8.2. Total cellular proteins were separated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and revealed by Western blot analysis using a phospho-Zap-70 or phospho-Erk1/2 antibody. Quantification of phosphorylation was calculated as the ratio between the signals of phospho-protein and the corresponding total protein.

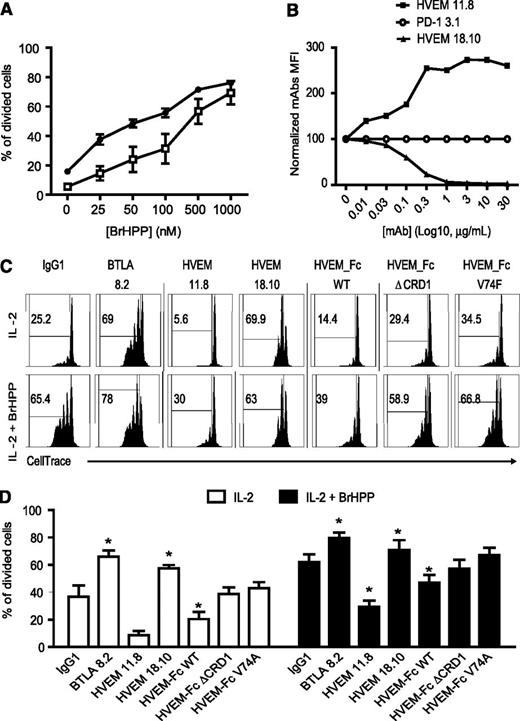

BTLA engagement by its ligand HVEM attenuates Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferative capacities

TCR-mediated activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells usually results in cytotoxicity and cytokine production. We first tested whether BTLA blockade could affect the cytotoxicity against the classical γδ T-cell target, the Daudi cell line. Surprisingly, BTLA blockade had no effect on the lysis of Daudi cells (supplemental Figure 3A). We also tested the lysis of the FL cell line, RL, by Vγ9Vδ2T cells. RL cells were resistant to γδ T cells, and BTLA blockade had no effect. Of note, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells express high amounts of intracellular granzymes. As expected, 24 hours after BrHPP+IL-2 stimulation, the content of intracellular granzyme B decreased. BTLA blockade had no effect on granzyme B production (data not shown). Furthermore, BTLA blockade did not affect the production of IFN-γ nor the target-independent degranulation induced by BrHPP (supplemental Figure 3B-C).

Upon cell activation and triggering of effector functions, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells usually undergo rapid proliferation. We next studied whether BTLA could affect proliferation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. First, highly purified Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were stimulated by IL-2+BrHPP for 5 days. Proliferative capacities were then assessed by measurement of CFSE dilution together with the monitoring of BTLA expression. BTLA negative cells (named “γδ BTLA–”) proliferated more than their BTLA-negative counterparts (Figure 4A). We next studied the role of BTLA-HVEM interaction with respect to proliferation, using mAb directed against BTLA, or its ligand HVEM, generated in our laboratory. The HVEM 11.8 mAb efficiently increased the binding of BTLA to HVEM-expressing cells, whereas the HVEM 18.10 mAb was selected for its ability to efficiently block this interaction (Figure 4B), and therefore has the same effect as the previously described antagonistic BTLA 8.2.26,32 Because the HVEM binding site for BTLA involves almost exclusively residues from CRD1, we generated 2 HVEM-FC mutants: HVEM-ΔCRD1 (deleted for the CRD1 domain), which had lost its ability to interact with BTLA; and HVEM-V74A (mutation of HVEM residue Val36 to alanine), which resulted in a tenfold reduction in BTLA affinity.42 When BTLA was engaged by its ligand HVEM (HVEM-Fc), we observed a significant inhibition of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation induced by IL-2+BrHPP (Figure 4C-D). Conversely, the blockade of BTLA-HVEM interaction with antagonist mAbs (BTLA 8.2 and HVEM 18.10) resulted in a significant increase in proliferation induced by IL-2+BrHPP (Figure 4C, lower panels; Figure 4D, right histogram). Importantly, the blocking effects of BTLA 8.2 or HVEM 18.10 mAbs were also observed without TCR stimulation by BrHPP (IL-2 alone, Figure 4C, upper panels; Figure 4D, left histogram), which suggests that the negative role of BTLA may be independent from the TCR signaling pathway. As a control, the 2 mutants of HVEM-Fc have no effect on Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation. These data showed that BTLA-HVEM interaction is a major pathway implicated in the negative regulation of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation.

BTLA-HVEM interaction inhibited γδ T-cell proliferation. (A) Circulating γδ cells from HV were purified and cultured with IL-2±25 to 1000 nM BrHPP during 5 days (n = 3). Proliferation was quantified by CFSE dilution and represented as the percentage of divided cells among γδ T cells. (B) Characterization of HVEM mAbs. Stable transfectants LTK-HVEM were pre-incubated for 1 hour with the indicated concentrations of anti-HVEM (HVEM 11.8 and HVEM 18.10), followed by the addition of human BTLA-Fc (10 µg/mL). Then transfectants were incubated for 30 minutes with GAH-PE (IM1626 Immunotech 1/100). PD1-3 mAb was included in the same conditions as the nonblocking control. Results were normalized by dividing MFI of HVEM mAbs by MFI of PD1-3.1 mAb (baseline level). (C-D) CellTrace dilution in purified-γδ T cells from 4 HV stimulated 5 days with or without low-dose BrHPP (50 nM) with specified mAb or Fc proteins. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was established using the nonparametric paired Wilcoxon U test. *P < .05; **0.001 < P < .01; ***P < .001.

BTLA-HVEM interaction inhibited γδ T-cell proliferation. (A) Circulating γδ cells from HV were purified and cultured with IL-2±25 to 1000 nM BrHPP during 5 days (n = 3). Proliferation was quantified by CFSE dilution and represented as the percentage of divided cells among γδ T cells. (B) Characterization of HVEM mAbs. Stable transfectants LTK-HVEM were pre-incubated for 1 hour with the indicated concentrations of anti-HVEM (HVEM 11.8 and HVEM 18.10), followed by the addition of human BTLA-Fc (10 µg/mL). Then transfectants were incubated for 30 minutes with GAH-PE (IM1626 Immunotech 1/100). PD1-3 mAb was included in the same conditions as the nonblocking control. Results were normalized by dividing MFI of HVEM mAbs by MFI of PD1-3.1 mAb (baseline level). (C-D) CellTrace dilution in purified-γδ T cells from 4 HV stimulated 5 days with or without low-dose BrHPP (50 nM) with specified mAb or Fc proteins. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was established using the nonparametric paired Wilcoxon U test. *P < .05; **0.001 < P < .01; ***P < .001.

Because BTLA expression was modulated during Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell differentiation (Figure 1C-D), we hypothesized that the inhibition of proliferation by BTLA may differ between the different differentiation stages of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Total Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were sorted by flow cytometry on the basis of CD45RA and CD27 expression and cultured 5 days with IL-2 and BrHPP. BTLA-HVEM interaction similarly affected both proliferation (supplemental Figure 4A-B) and activation (supplemental Figure 4C) of naïve cells and cells that have already encountered Ag. Interestingly, a better binding of HVEM to BTLA limited the naïve and CM cells transition to effector cells (supplemental Figure 4D). Altogether, our data support a role of BTLA as a regulator of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation, activation, and differentiation.

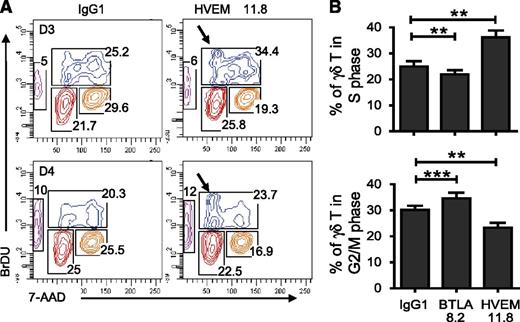

BTLA-HVEM interaction induces partial S-phase arrest

Our results suggested that, like the B7-CTLA-4 pathway,43,44 BTLA-HVEM interaction might exert its major effect on Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell immune response via regulation of the cell cycle. Treatment with agonistic anti-HVEM mAb of IL-2+BrHPP–stimulated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells resulted in a significantly higher percentage of phenotypically naïve cells in S phase (P = .0024; Figure 5A, arrow; Figure 5B) compared with anti–IgG1-treated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Figure 5A). The percentage of subG0 cells (apoptotic cells) was not affected by engagement of BTLA, suggesting that after exposure to mAb for 72 hours, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells do not undergo apoptosis. Conversely, blocking BTLA engagement resulted in a slight but significant (P = .0049) decrease in the percentage of cells in S phase and an increase (P = .0005) in the G2/M phase (Figure 5B). Altogether, these data showed that BTLA engagement reduces Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation capabilities as a result of partial S-phase arrest.

BTLA-HVEM engagement induces partial S-phase arrest. (A) Representative result showing the time course study of in vitro BrdU pulsing Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after 3 days (upper panel) and 4 days (lower panel) in culture with IL-2 + BrHPP (50 nM) ± HVEM 11.8 or IgG1. (B) Percentage of naïve Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in the S phase (upper panel) or in the G2/M phase (lower panel) after 3 days in culture with IL2+BrHPP±IgG1 or HVEM 11.8 (n = 12). Cells that may be in transition between 2 proliferation stages were excluded. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was established using the nonparametric paired Wilcoxon U test. *P < .05; **0.001 < P < .01; ***P < .001.

BTLA-HVEM engagement induces partial S-phase arrest. (A) Representative result showing the time course study of in vitro BrdU pulsing Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after 3 days (upper panel) and 4 days (lower panel) in culture with IL-2 + BrHPP (50 nM) ± HVEM 11.8 or IgG1. (B) Percentage of naïve Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in the S phase (upper panel) or in the G2/M phase (lower panel) after 3 days in culture with IL2+BrHPP±IgG1 or HVEM 11.8 (n = 12). Cells that may be in transition between 2 proliferation stages were excluded. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was established using the nonparametric paired Wilcoxon U test. *P < .05; **0.001 < P < .01; ***P < .001.

BTLA-HVEM blockade increases Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation in co-culture with HVEM+ lymphoma cells

Insofar as HVEM is widely expressed by other immune cells, notably by B cells but also by tumor cells, we next wondered whether HVEM-expressing tumor cells could affect Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation. First, as a surrogate for tumor cells, we used the FL cell line RL that expressed HVEM but not CD160 and LIGHT (supplemental Figure 5A). CellTrace-labeled Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were then co-incubated for 5 days with or without irradiated RL cells in the absence or presence of IL-2 ±BrHPP. We first observed that RL cells induced a significant decrease of CellTrace dilution in unstimulated or BrHPP-stimulated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (P = .0117, supplemental Figure 5B-C). Blocking BTLA with antagonist mAbs strongly increased the proliferation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (supplemental Figure 5B-C). Although B cells express high amounts of Fc receptor, the Fab of anti-BTLA 8.2 resulted in a similar increase of proliferation. To investigate BTLA-HVEM interactions in the tumor microenvironment, we have mechanically disrupted lymph nodes from 11 patients with several types of lymphoma and resuspended cells to perform multiparametric flow cytometry analysis. On each sample we evaluated the HVEM expression on neoplastic cells (69.3% ± 6.88 on NHL) (Figure 6A-B, right panel, gated on CD5-CD20+ cells) and the expression of BTLA, CD160, and LIGHT on cytotoxic effectors present in tumor microenvironment such as NK cells, αβ T cells, and γδ T cells (Figure 6A-B, left and middle panels). We found that BTLA is restricted to the T-cell compartment (59% ± 5.3 and 57.7% ±7.4 on γδ T cells and αβ T cells, respectively), whereas CD160 and LIGHT were absent. Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were mostly of the CM phenotype (Figure 6D) and their BTLA expression profile was in line with that of HV (Figure 1B). Hence, BTLA appears as the main ligand for HVEM present on the tumor microenvironment. We next stained Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with CellTrace to assess their proliferative capacities after 5 days of coculture with autologous lymphoma cells and IL-2 in the presence or absence of blocking mAb directed against HVEM or BTLA. The blockade of BTLA-HVEM interaction resulted in a significant increase (HVEM 18.10 P = .0029; BTLA 8.2 P = .0049 or Fab BTLA 8.2 P = .0078) in Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation (Figure 6E). Notably, we found similar results with αβ T cells (Figure 6F). Altogether, our data showed that HVEM-positive lymphoma cells have the potential to reduce the proliferation of intranodal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in a BTLA-dependent manner.

BTLA blockade restored γδ T-cell proliferation in co-culture with HVEM+ lymphoma cells. (A) Percentage of BTLA-positive cells among Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from patients with inflammatory lymph nodes (IF-LN), NHL, and HL. (B) Gating strategy for evaluating HVEM expression on tumor cells and BTLA, CD160, and LIGHT expression on αβ T, γδ T, and NK cells. (C) Percentage of BTLA, CD160, and LIGHT expression on αβ T, γδ T, and NK cells and percentage of HVEM-expressing cells among lymphoma cells (n = 11). (D) Representative experiment showing BTLA expression according to γδ T-cell differentiation subsets within lymph nodes. BTLA expression on intranodal γδ T cells from lymphoma in the patient in (B), γδ T cells were analyzed for CD45RA and CD27 expression, resulting in the following subsets of γδ T lymphocytes: naïve (CD45RA+CD27+), CM (CD45RA−CD27+), EM (CD45RA−CD27−), and TEMRA (CD45RA+CD27−). (E-F) CellTrace dilution gated on intranodal γδ T cells (n = 11) stimulated 5 days with IL-2 and specified mAb. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was established using the nonparametric paired Wilcoxon U test. *P < .05; **0.001 < P < .01; ***P < .001.

BTLA blockade restored γδ T-cell proliferation in co-culture with HVEM+ lymphoma cells. (A) Percentage of BTLA-positive cells among Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from patients with inflammatory lymph nodes (IF-LN), NHL, and HL. (B) Gating strategy for evaluating HVEM expression on tumor cells and BTLA, CD160, and LIGHT expression on αβ T, γδ T, and NK cells. (C) Percentage of BTLA, CD160, and LIGHT expression on αβ T, γδ T, and NK cells and percentage of HVEM-expressing cells among lymphoma cells (n = 11). (D) Representative experiment showing BTLA expression according to γδ T-cell differentiation subsets within lymph nodes. BTLA expression on intranodal γδ T cells from lymphoma in the patient in (B), γδ T cells were analyzed for CD45RA and CD27 expression, resulting in the following subsets of γδ T lymphocytes: naïve (CD45RA+CD27+), CM (CD45RA−CD27+), EM (CD45RA−CD27−), and TEMRA (CD45RA+CD27−). (E-F) CellTrace dilution gated on intranodal γδ T cells (n = 11) stimulated 5 days with IL-2 and specified mAb. Results were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was established using the nonparametric paired Wilcoxon U test. *P < .05; **0.001 < P < .01; ***P < .001.

Discussion

The co-receptor BTLA has been extensively studied on conventional αβ T cells, in which it attenuates activation and proliferation.21,24 In this study, we show for the first time that BTLA is implicated in the regulation of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation and differentiation. In addition, the BTLA-HVEM pathway is a major actor in the control of Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell proliferation by lymphoma B cells. These findings have potent implications for the understanding of γδ T-cell responses during the course of various diseases, viral infections, and cancer progression. Hence, manipulation of these pathways may be highly relevant for developing effective tumor immunotherapy.

We first examined the expression of BTLA on different human peripheral blood γδ T-cell subsets. We observed that resting γδ T cells expressed a high level of BTLA, particularly on the naïve population. However this expression was downregulated in the CM and EM stages compared with γδ naïve T cells. In contrast, PD-1 is preferentially expressed on Temh1 γδ T-cell subsets.32 Moreover, PD-1 expression was upregulated after TCR engagement, whereas that of BTLA was drastically down-modulated. These data reveal a different regulation of expression of BTLA and PD-1, which may reflect different functions. For instance, it has been suggested that PD-1 upregulation may participate in the contraction of T-cell immune response after an immune challenge. In contrast, BTLA may serve as a regulator of immune response initiation, similarly to inducible cosimulator and B7 molecules. For instance, enhancing BTLA-HVEM interaction with agonistic mAbs resulted in a 25% reduction of the percentage of effector cells compared with isotype control after IL-2+BrHPP stimulation. This result indicates that this co-signaling pathway may regulate human γδ T-cell differentiation. Accordingly, recent data showed a direct role of the B7/CTLA-4 interaction on the Th17 differentiation.45

From a functional perspective, the present study provides evidence that BTLA is a new inhibitory molecule for human γδ T-cell activation. Hence, we have shown that BTLA is expressed closely to the TCR at the surface of activated γδ T cells and at the synapse between γδ T cells and HVEM+ target cells. Western blot analyses showed that γδ TCR proximal signaling is improved after BTLA blockade, revealing BTLA as a repressor of γδ TCR signaling, as previously described for αβ TCR signaling.18 Critically, these new observations may help our understanding of the kinetics of γδ T-cell responses during the course of various autoimmune diseases and provide a basis for developing therapeutic approaches aimed at modulating overreacting inflammatory responses. It is important to note that γδ T cells also express HVEM. Hence, BTLA-HVEM interaction between γδ T cells occurs in the absence of “target cells.” Moreover, recent studies have revealed that HVEM and BTLA could interact in cis.46,47 Therefore, the use of a blocking anti-BTLA antibody as a single reagent is expected to induce a response in the absence of a HVEM-positive partner cell.

As a consequence of BTLA function on TCR signaling, we have observed that BTLA negatively regulated γδ T-cell proliferation, and that BTLA engagement during γδ T-cell activation induced a partial arrest in the S phase. These data are consistent with previous data obtained on αβ T cells.48,49 Induction of γδ T-cell response is associated, like for αβ T cells, with a strong expansion. Our data suggest that BTLA may participate in the regulation of this early event. Interestingly, previous studies on BTLA knockout mice have evidenced a pro-survival role of BTLA for T cells in different models of immune challenge.50,51 In humans, our in vitro results suggest that BTLA exerts mainly inhibitory function on CMV-specific memory T cells and would control the expansion of the CMV-specific T cells.32 In our current study, we failed to identify a role of BTLA in survival because most γδ T cells die rapidly in vitro without exogenous cytokines.

Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are strongly activated and kill lymphoma cells. The antitumor activity of γδ T cells is largely dependent on cell-cell contact and their modulation by co-stimulatory and inhibitory signals may play a role in preventing γδ T-cell responses to tumors. In lymphoma tissue samples, we observed that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are present in low numbers and thus probably require extensive proliferation to conduct an efficient control of tumor progression. We found that blockade of BTLA-HVEM interaction allowed a better spontaneous or TCR-induced proliferation of γδ T cells in coculture with allogeneic and autologous HVEM+ lymphoma cells. These data suggest that lymphoma cells may exert a control over γδ T-cell expansion using a BTLA-HVEM–dependent pathway. Recent reports have described frequent loss-of-function mutations in HVEM/TNFRSF14 in FL tissues.35,36 Launay et al have identified several mutations in the TNFRSF14 gene that are correlated with a better prognosis.36 Our data are in line with this study, because we could extrapolate that the loss of BTLA-HVEM interaction in the tumor microenvironment may favor γδ T-cell expansion. However, further studies are required to confirm this putative model, because the prognostic value of TNFRSF14 mutation in lymphoma patients remains controversial.35 Larger series are also needed to perform statistical analyses comparing the proliferative capacities of intratumor γδ T cells between HVEM-mutated and nonmutated lymphoma patients. Eventually, our data suggest a novel, previously undescribed, pathway for tumor cell escape from γδ T cell–mediated immune responses. Hence, this study provides an important baseline to further investigation of the γδ T-cell response in the lymphoma microenvironment, which appears as a potential target for immunotherapies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Phillipe Livrati and Sylvaine Just-Landi for excellent technical support, and the tumor biobank of the Institute Paoli-Calmettes, led by Prof Chabannon, for the supply of clinical samples.

Authorship

Contribution: J.G.-D. designed research, performed experimental work, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the paper; C.F. analyzed and interpreted data and drafted the paper; M.-L.T. performed experimental work and analyzed data; S.P. performed experimental work; J.F. and L.X. contributed to the design of the project research and contributed to draft the paper; F.O. performed experimental work; R.B. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; and D.O. designed research, contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and helped draft the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel Olive, Aix Marseille Université CRCM U1068 INSERM, Institut Paoli Calmettes 27 Bd Leï Roure, 13009 Marseille, France; e-mail: daniel.olive@inserm.fr; and Julie Gertner-Dardenne, Aix Marseille Université CRCM U1068 INSERM, Institut Paoli Calmettes 27 Bd Leï Roure, 13009 Marseille, France; email: j.gertner-dardenne@hotmail.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal