Key Points

PRCP influences cell growth independent of its active site.

PRCP loss has reduced angiogenesis, wound healing, and ischemic/wire injury repair.

Abstract

Prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP) is associated with leanness, hypertension, and thrombosis. PRCP-depleted mice have injured vessels with reduced Kruppel-like factor (KLF)2, KLF4, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and thrombomodulin. Does PRCP influence vessel growth, angiogenesis, and injury repair? PRCP depletion reduced endothelial cell growth, whereas transfection of hPRCP cDNA enhanced cell proliferation. Transfection of hPRCP cDNA, or an active site mutant (hPRCPmut) rescued reduced cell growth after PRCP siRNA knockdown. PRCP-depleted cells migrated less on scratch assay and murine PRCPgt/gt aortic segments had reduced sprouting. Matrigel plugs in PRCPgt/gt mice had reduced hemoglobin content and angiogenic capillaries by platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) and NG2 immunohistochemistry. Skin wounds on PRCPgt/gt mice had delayed closure and reepithelialization with reduced PECAM staining, but increased macrophage infiltration. After limb ischemia, PRCPgt/gt mice also had reduced reperfusion of the femoral artery and angiogenesis. On femoral artery wire injury, PRCPgt/gt mice had increased neointimal formation, CD45 staining, and Ki-67 expression. Alternatively, combined PRCPgt/gt and MRP-14−/− mice were protected from wire injury with less neointimal thickening, leukocyte infiltration, and cellular proliferation. PRCP regulates cell growth, angiogenesis, and the response to vascular injury. Combined with its known roles in blood pressure and thrombosis control, PRCP is positioned as a key regulator of vascular homeostasis.

Introduction

The serine protease prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP, lysosomal carboxypeptidase, PCP) influences systemic blood pressure and vascular anticoagulation.1 First isolated from the lysosomal fraction of renal cortical cells, it now is identified both immunochemically and genetically as a membrane protein on endothelial cells.2-4 PRCP gene-trap mice (PRCPgt/gt) were created using a targeting vector directed to genes whose proteins are expressed on cell membranes.1,4 As a peptidase, PRCP’s substrates have a penultimate C-terminal proline (Pro-X) such as bradykinin1-8, angiotensin II (Ang II), or angiotensin III.2,5,6 Endothelial cell membrane or matrix PRCP also activates plasma prekallikrein (PK) to plasma kallikrein with high affinity, liberating the vasoactive peptide bradykinin (BK).3,7-9

Because PRCP degrades vasoactive peptides bradykinin1-8 and Ang II, it has been proposed as a protein associated with hypertension.10 SNP studies suggest that a PRCP E112D polymorphism is associated with hypertension in 2 of 3 studies.11-13 PRCPgt/gt mice that are PRCP-deficient but not deleted, have mild hypertension with renal histologic changes.1 In addition, PRCP converts αMSH1-13 to αMSH1-12 and PRCPgt/gt mice are lean.4 PRCPgt/gt mice have constitutive anorexia because of decreased αMSH1-13 metabolism with increased glucose tolerance and less insulin resistance.4,14 Consistent with these findings, individuals with diabetes, obesity, or acute coronary syndrome have elevated plasma PRCP levels.15 In spite of being metabolically protected, PRCPgt/gt mice are not healthy. Along with hypertension, they have shortened times to induced arterial thrombosis.1 The unifying mechanism for hypertension and thrombosis in PRCPgt/gt mice is that PRCP deficiency is associated with increased vascular and renal reactive oxygen species.1 Tissue damage due to heightened reactive oxygen species results in reduced vasoprotective transcription factors Kruppel-like factor (KLF)2 and KLF4, with secondary downregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and thrombomodulin and elevated tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.1,16-18 Even in the presence of improved metabolism, cardiovascular defects are the major phenotype of PRCP-deficient mice.1,14

PRCP also has been proposed as a gene involved in vascular development.19 In the cell adhesion molecule (CAM) assay, it is expressed on days E7-E10 along with several transcription and growth factors and its expression is enriched in glioblastoma tissue compared with normal brain tissue.19 Furthermore, PRCP overexpression in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer cells confers autophagy and resistance to tamoxifen.20 These data suggest that PRCP additionally contributes to cell proliferation and angiogenesis. The present investigations examine the contribution of PRCP to cell growth and migration and angiogenesis. In vitro, PRCP deficiency results in decreased endothelial cell growth, slower cell migration, and decreased aortic sprouting. In vivo, PRCPgt/gt mice demonstrate decreased wound repair and Matrigel angiogenesis. They also have defective repair of large-vessel damage from limb ischemia and wire injury. These combined data indicate that PRCP promotes vascular health and its deficiency results in impaired endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis associated with vascular injury.

Methods

Animals

All mice were on a C57BL/6 genetic background and were maintained in animal facilities at Case Western Reserve University. Animal care and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and the National Institutes of Health. PRCPgt/gt mice were created from KST302 ES cells obtained from Bay Genomics.1,4 Combined PRCPgt/gt and MRP-14−/− mice were prepared by mating.20

Cell culture and transfections

Passage 2-4 bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) were obtained (Cell Systems), grown in MCDB-131 Complete Media with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (VEC Technologies) on gelatin-coated plates. BAEC were grown to near-confluence in 6-well plates and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) in OPTI-MEM medium (Invitrogen). RNA used for siRNA inhibition of PRCP expression was obtained from Invitrogen (see supplemental Table 1). Overexpression of human PRCP cDNA (hPRCP) was performed using a plasmid in pcDNA5/FRT/TO-TOPO-TA (Invitrogen) with a trypsin II signal sequence containing the sequence for mature, full-length human PRCP (hPRCP) (Mr∼55 kDa) starting at N47.7 For mutated hPRCP (hPRCPmut), alanine substitutions were made by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the hPRCP cDNA template at positions S179 and H455 of the catalytic triad. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell growth, apoptosis, and migration assays

Cell images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope and a Nikon 10×/0.25 objective lens. Actual cell counts were obtained from cell images. The MTS [3-(4,5-dimethylthia-zol-2-yl)-5-(3-caroxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] assay (Promega) was performed to assess cell number and viability. MTS reagent (100 μL) was added to cells in 1 mL of media for 60 minutes at 37°C. Readings were obtained at UV wavelength 490 nm using a NOVOstar plate-reader (BMG Labtech) and presented as percent growth change. Annexin V binding was performed using an Alexa-594 tagged Annexin V protein (Invitrogen) added to BAEC for 15 minutes at 37°C in 10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 25 mM CaCl2 buffer. Fluorescent images of Annexin-V–treated cells were analyzed with MetaMorph software Version 7 (Molecular Devices), and values were obtained by calculating pixel density per field. The cell scratch migration assay was performed using a 200-μL pipet tip to remove confluent cells from the plate. Images were obtained at the same locations on the scratch by marking the bottom of the culture plate with a razor blade. Cell migration was calculated by the distance between the cell edges at 0 hours minus the distance at 5 hours divided by 2. Each distance was measured as scratch width as determined by morphometric analysis by MetaMorph software Version 7 (Molecular Devices).

Methods for immunohistochemistry, angiogenesis investigations, wound injury, limb ischemia, wire injury, and statistical analysis can be found in the supplemental Methods.

Results

PRCP and endothelial cell growth

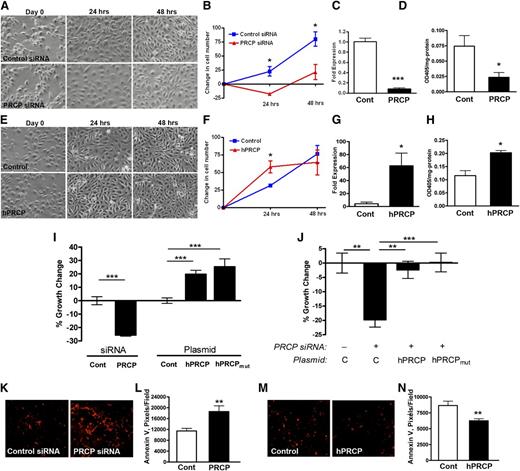

We observed that PRCP knockdowns of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and BAEC resulted in fewer cells at 24 and 48 hours. Because BAEC preserve their BK B2 receptor longer than HUVECs,21 the following studies were performed with them. Starting with equal cell numbers, PRCP siRNA knockdown decreased the number of cells per high-power field (HPF) (–18 ± 3 cells/HPF, mean ± SD) at 24 hours compared with control siRNA treated cells (+23 ± 8 cells/HPF) (Figure 1A-B). This difference persisted at 48 hours. Treatment of BAEC with PRCP siRNA resulted in 8.3% PRCP mRNA expression relative to treatment with control siRNA (Figure 1C). Likewise, on BAEC treated with PRCP siRNA, there was a 75% reduction in membrane PRCP determined by PK activation (Figure 1D).

PRCP levels modulate endothelial cell growth. (A) BAEC were transfected with control or PRCP siRNA, and images were taken at time 0 (D0) and at 24 and 48 hours. (B) Graphic data represent mean ± SD changes in cell numbers per field compared with mean D0 values (n = 3 for both groups). (C) Relative bovine PRCP mRNA expression after siRNA transfections (Cont vs PRCP) on quantitative PCR (n = 5 for both groups). (D) Relative PK activation by expressed bovine PRCP as determined by OD405 nm/mg protein of cells (n = 3 for both groups). (E) BAEC were transfected with Control (vector) or hPRCP (plasmid expressing the full length mature human PRCP), and images were taken at time 0 (D0) and at 24 and 48 hours. (F) Graphic data represent mean ± SD changes in cell numbers per field compared with mean D0 values (n = 3 for both groups). (G) Relative human PRCP mRNA expression after vector (Cont) or hPRCP transfection on quantitative PCR (n = 5 for both groups). (H) Relative PK activation by expressed PRCP after hPRCP transfection as determined by OD405 nm/mg protein of cells (n = 9 in both groups). (I) The % growth change of BAEC after siRNA (Cont or PRCP) or plasmid (Cont, hPRCP, hPRCPmut) transfections as measured by a MTS cell assay (n ≥ 5 for all groups). (J) The % growth change of BAEC transfected with PRCP siRNA (+) (n = 9) without (C) or with hPRCP (n = 15) or hPRCPmut plasmid (n = 15). (K) Alexa-594–labeled Annexin V expression on BAEC after Control and PRCP siRNA transfection. (L) The relative Annexin V expression (pixels/field) on BAEC after Control and PRCP siRNA transfection from (K) (n ≥ 12 for both groups). (M) Alexa-594–labeled Annexin V expression on BAEC after Control and hPRCP transfection. (N) The relative pixels/field of Annexin V expression on BAEC after Control and hPRCP transfection from (M) (n > 12 for both groups). All images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope with a 10×/0.25 objective lens. The figures are expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 of comparisons between 2 groups.

PRCP levels modulate endothelial cell growth. (A) BAEC were transfected with control or PRCP siRNA, and images were taken at time 0 (D0) and at 24 and 48 hours. (B) Graphic data represent mean ± SD changes in cell numbers per field compared with mean D0 values (n = 3 for both groups). (C) Relative bovine PRCP mRNA expression after siRNA transfections (Cont vs PRCP) on quantitative PCR (n = 5 for both groups). (D) Relative PK activation by expressed bovine PRCP as determined by OD405 nm/mg protein of cells (n = 3 for both groups). (E) BAEC were transfected with Control (vector) or hPRCP (plasmid expressing the full length mature human PRCP), and images were taken at time 0 (D0) and at 24 and 48 hours. (F) Graphic data represent mean ± SD changes in cell numbers per field compared with mean D0 values (n = 3 for both groups). (G) Relative human PRCP mRNA expression after vector (Cont) or hPRCP transfection on quantitative PCR (n = 5 for both groups). (H) Relative PK activation by expressed PRCP after hPRCP transfection as determined by OD405 nm/mg protein of cells (n = 9 in both groups). (I) The % growth change of BAEC after siRNA (Cont or PRCP) or plasmid (Cont, hPRCP, hPRCPmut) transfections as measured by a MTS cell assay (n ≥ 5 for all groups). (J) The % growth change of BAEC transfected with PRCP siRNA (+) (n = 9) without (C) or with hPRCP (n = 15) or hPRCPmut plasmid (n = 15). (K) Alexa-594–labeled Annexin V expression on BAEC after Control and PRCP siRNA transfection. (L) The relative Annexin V expression (pixels/field) on BAEC after Control and PRCP siRNA transfection from (K) (n ≥ 12 for both groups). (M) Alexa-594–labeled Annexin V expression on BAEC after Control and hPRCP transfection. (N) The relative pixels/field of Annexin V expression on BAEC after Control and hPRCP transfection from (M) (n > 12 for both groups). All images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope with a 10×/0.25 objective lens. The figures are expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 of comparisons between 2 groups.

Using a plasmid containing cDNA for full-length mature human PRCP (amino acids 47-496), the reciprocal experiment was performed. Overexpression of hPRCP cDNA in BAEC increased the cell count (58 ± 9 cells/HPF) compared with control plasmid (31 ± 2 cells/HPF) at 24 hours (Figure 1E-F). BAEC transfected with hPRCP demonstrated expression of human PRCP mRNA and there was an approximately twofold increase in membrane-associated PRCP’s ability to activate PK (Figure 1G-H).

Additional studies were performed using a cell proliferation assay. Twenty-four hours after PRCP siRNA knockdown, there was 26 ± 1% BAEC growth reduction compared with treatment with control siRNA (Figure 1I). Alternatively, when hPRCP was transfected into BAEC, there was a 19 ± 12% growth increase (Figure 1I). Presumably, the increased cell growth with hPRCP transfection was related to its protease activity. When HK and PK are incubated with BAEC, the HK-bound PK becomes activated by PRCP, and BK is liberated.21 However, assembly of HK and PK in the absence or presence of lisinopril to prevent angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) degradation of formed BK was unable to correct the growth inhibition seen in BAEC transfected with PRCP siRNA (supplemental Figure 1A). Furthermore, the addition of 100 to 1000 nM BK, Ang-(1-7), or Ang II to BAEC cultures after PRCP siRNA treatment was unable to rescue the growth reduction (supplemental Figure 1B-D). These data suggested that the influence of PRCP on BAEC growth was independent of its major substrates and products. To examine these observations further, BAEC were transfected with a plasmid of hPRCP, where cDNA for 2 active site amino acids was mutagenized to alanine (S179A, H455A) (hPRCPmut). Transfection of hPRCPmut into BAEC increased cell growth by 25 ± 6% (Figure 1I). In addition, cotransfection of hPRCP or hPRCPmut with PRCP siRNA rescued the growth reduction in the cells and restored the cell counts to treatment with control plasmid alone (Figure 1J). These data indicated that PRCP regulated cell growth, but this activity was independent of its active site.

PRCP levels also influenced apoptosis as determined by Annexin V binding. In BAEC treated with PRCP siRNA, there was a 1.6-fold increased Annexin V fluorescence (Figures 1K-L). Alternatively, when hPRCP was overexpressed, there was a 28% decrease in Annexin V binding compared with control (Figures 1M-N). The presence of Annexin V in control siRNA is the effect of the transfection agents (lipofectamine, siRNA) themselves on induction of cell apoptosis (data not shown).

PRCP and angiogenesis

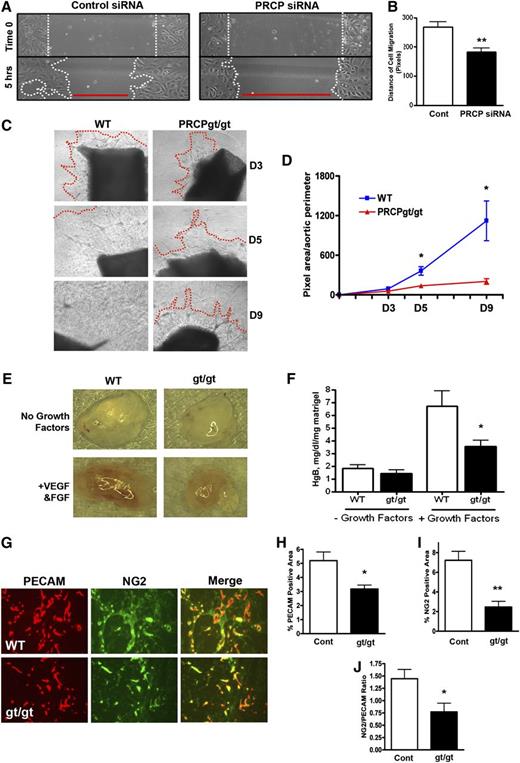

Because PRCP influences embryonic angiogenesis, we determined whether its effect on cell growth influenced the angiogenic response.19,22 On a cell scratch migration assay with BAEC, the size of the scratch wound closure was 68% less for PRCP depleted cells (183 ± 14 pixel distance of cell migration) than for control cells (268 ± 18 pixel distance of cell migration) (P < .0019) (Figure 2A-B). These data indicate that PRCP-depleted cells have a migration defect. Aortic sprouts from PRCPgt/gt mice were significantly reduced on both day 5 (137 ± 23 pixel area for PRCPgt/gt vs 362 ± 65 for wild-type [WT]) and day 9 (203 ± 41 pixel area for PRCPgt/gt vs 1121 ± 301 for WT) (Figure 2C-D).

Influence of PRCP on angiogenesis. (A) Confluent BAEC transfected with Control or PRCP siRNA were “scratched” and images were obtained initially (“Time 0”) and after 5 hours. (B) The distance of cell migration from (A) as determined by MetaMorph analysis was obtained by subtracting 5-hour widths from Time 0 divided by 2 (n = 9 for both groups). (C) Endothelial sprouting of aortic segments from WT and PRCPgt/gt mice were photographed on D3, D5, and D9. The red line indicates the leading edge of the sprout. The absence of a red line indicates the sprouting was beyond the field of view. (D) Morphometric analysis of images in (C) expressed as the mean ± SEM of the pixel area of sprouts per aortic perimeter. (E) A Matrigel plug containing no growth factors or with vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor were injected subcutaneously into WT or PRCPgt/gt mice (n = 13-17 for all 4 groups). Gross Matrigel plug images were obtained using a Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope (original magnification ×1). (F) Hemoglobin content on homogenized Matrigel plugs from the 4 conditions in (E) harvested on D9. (G) Frozen sections of Matrigel plugs from WT or PRCPgt/gt (gt/gt) mice were stained for the endothelial cell marker PECAM (red) and VSMC marker NG2 (green). The percent PECAM (CD31)-positive (H) or NG2 positive (I) area was assessed by morphometric analysis (n > 4 for all Matrigel stain analysis). (J) The ratios between NG2 and PECAM-positive stained areas within each image were obtained. Migration and sprout images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope with a 10×/0.25 objective lens, 20×/0.45 for Matrigel plug staining images. *P < .05, **P < .01 of comparison between 2 groups.

Influence of PRCP on angiogenesis. (A) Confluent BAEC transfected with Control or PRCP siRNA were “scratched” and images were obtained initially (“Time 0”) and after 5 hours. (B) The distance of cell migration from (A) as determined by MetaMorph analysis was obtained by subtracting 5-hour widths from Time 0 divided by 2 (n = 9 for both groups). (C) Endothelial sprouting of aortic segments from WT and PRCPgt/gt mice were photographed on D3, D5, and D9. The red line indicates the leading edge of the sprout. The absence of a red line indicates the sprouting was beyond the field of view. (D) Morphometric analysis of images in (C) expressed as the mean ± SEM of the pixel area of sprouts per aortic perimeter. (E) A Matrigel plug containing no growth factors or with vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor were injected subcutaneously into WT or PRCPgt/gt mice (n = 13-17 for all 4 groups). Gross Matrigel plug images were obtained using a Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope (original magnification ×1). (F) Hemoglobin content on homogenized Matrigel plugs from the 4 conditions in (E) harvested on D9. (G) Frozen sections of Matrigel plugs from WT or PRCPgt/gt (gt/gt) mice were stained for the endothelial cell marker PECAM (red) and VSMC marker NG2 (green). The percent PECAM (CD31)-positive (H) or NG2 positive (I) area was assessed by morphometric analysis (n > 4 for all Matrigel stain analysis). (J) The ratios between NG2 and PECAM-positive stained areas within each image were obtained. Migration and sprout images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope with a 10×/0.25 objective lens, 20×/0.45 for Matrigel plug staining images. *P < .05, **P < .01 of comparison between 2 groups.

In a murine Matrigel plug angiogenesis assay, there was essentially no growth into plugs without growth factor; growth into Matrigel plugs occurred when supplemented with vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in both WT and PRCPgt/gt hosts (Figure 2E). When the hemoglobin content of the Matrigel plugs was examined, growth factor–induced angiogenesis was increased in plugs in WT and PRCPgt/gt mice (Figure 2F). However, the hemoglobin content in Matrigel plugs injected in PRCPgt/gt mice (3.5 ± 0.5 Hgb mg/dL per mg Matrigel) was significantly less (P < .05) compared with WT mice (6.7 ± 1.2 Hgb mg/dL per mg Matrigel) (Figure 2F). The endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) content of the vessels in the Matrigel plugs were examined.23 Frozen sections of Matrigel plugs were stained for endothelial (Figure 2G, red) and pericyte/vascular smooth muscle cells (Figure 2G, green) using antibodies against platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) and NG2, respectively.24 On analysis of the immunofluorescence, PRCPgt/gt plugs demonstrated decreased PECAM (Figure 2H) and NG2 (Figure 2I) expression. Furthermore, the ratio of NG2/PECAM ratio was decreased in PRCPgt/gt plugs, suggesting a delay in vascular smooth muscle to endothelial cell growth in this neoangiogenic process (Figure 2J).

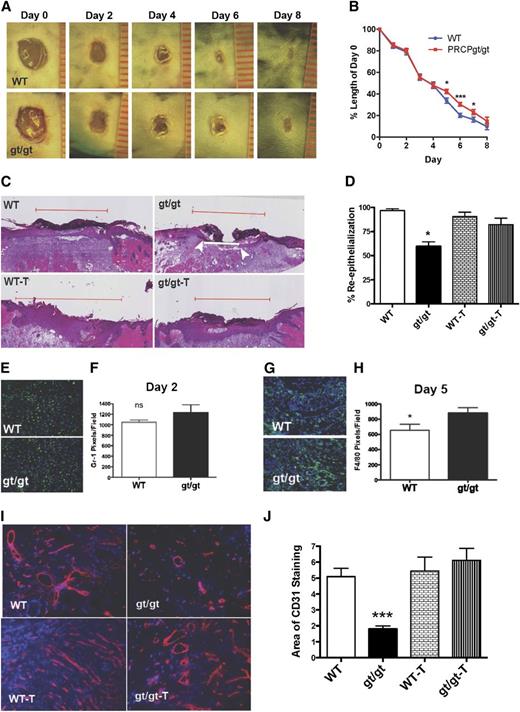

Wound repair of the PRCPgt/gt mouse

It was observed that during the initial time of wound healing (days 0-4), wound sizes in PRCPgt/gt or WT mice were unchanged (Figure 3A-B). At day 5 after wounding, PRCPgt/gt wounds had delayed closure compared with WT wounds (Figure 3A-B). When graphed as the percentage closed wounds per day post-wounding, on day 6, the number of healed wounds in PRCPgt/gt mice was half (42% vs 82%) that of WT (P < .0195 by log-rank Mantel-Cox analysis). To further evaluate wound healing, we examined the percent reepithelialization of the wounds on day 5. Wounds from WT mice reepithelialized faster than wounds from PRCPgt/gt mice (Figure 3C). The mean percent reepithelialization in WT mice (97 ± 2%, mean ± SEM) was significantly greater than that of PRCPgt/gt mice (60 ± 5%) (P < .0001) (Figure 3D). When PRCPgt/gt mice were treated for 1 week before wounding with an oral ACE inhibitor, the percent reepithelialization corrected to that seen in untreated and treated WT mice (Figure 3C-D) (P < .0009 on 1-way ANOVA). To better understand the mechanism, we examined both the inflammatory and angiogenic response in wounds. On day 2, the cell count of the leukocyte marker CD11b was unchanged in the wounded area of WT (61 ± 8 cells/image) vs PRCPgt/gt (67 ± 15 cells/image) mice. Likewise, when we examined the neutrophil response using anti–Gr-1 (Figure 3E-F) and macrophage infiltration using anti-F4/80 (data not shown), there also was no significant difference, indicating that the early inflammatory response was not altered.25 However, when day 5 wounds were examined for macrophages, PRCPgt/gt mice had significantly increased (P < .05) anti-F4/80 immunofluorescence (Figure 3G-H). We next examined the angiogenic phase of wound healing because this occurs in the latter portion of the process.26 Unwounded skin from PRCPgt/gt and WT mice did not have any difference in CD31 expression (data not shown). However, when day 5 wounds were characterized for CD31, there was a significant decrease in PECAM in the PRCPgt/gt wounds, indicating an angiogenic defect (Figure 3I-J). Prior treatment of PRCPgt/gt mice with an ACE inhibitor restored the angiogenic response, promoting wound healing. These findings indicate that the slowed wound closure in PRCPgt/gt mice is caused by an angiogenic defect and prior ACE inhibitor treatment improved the repair response.

Influence of PRCP on skin wound healing. (A) Full-thickness wounds from WT and PRCPgt/gt mice were imaged at D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8. Each unit on the ruler equals 1 mm in length. External wound images were obtained using a Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope (original magnification ×1). (B) Wound lengths are expressed relative to D0 length (n = 10 in both groups). On 2-way analysis of variance, the PRCPgt/gt wounds closed significantly slower (P < .047). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides from D5 wounds of WT and PRCPgt/gt (gt/gt) mice that were untreated or treated with ramipril (T) were analyzed for their extent of reepithelialization. The red line demarcates the total length of the original wound; the white line represents the “wound gap.” The white arrows indicate the end of the epithelial tongues of a closing wound. In photographs in which no white line is seen, the wound gap is 0 and the wound has completely reepithelialized. (D) The percent reepithelialization is shown for WT (n = 21), gt/gt (n = 6), WT-T (n = 16), and gt/gt-T (n = 13) mice. (E) Frozen sections of D2 wounds were stained with anti–Gr-1 to assess neutrophil infiltration. (F) Mean number of neutrophils as pixels/HPF, 20× on microscopy (n = 6 in both groups). (G) Frozen sections from D5 skin wounds were stained for F4/80 to assess macrophage infiltration. (H) Mean number of macrophages as pixels/HPF on microscopy (n > 8 in both groups). (I) CD31 staining on frozen sections from D5 wounds in WT, gt/gt, WT-T, and gt/gt-T were obtained. (J) The area of CD31 staining in the 4 groups of animals was compared by morphometric analysis using the National Institutes of Health’s ImageJ software (n ≥ 5 in all groups). Fluorescent wound images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope with a 20×/0.45 for Matrigel plug images. The following in the figure indicate group paired Student t-test P values: *P < .05, ***P < .001.

Influence of PRCP on skin wound healing. (A) Full-thickness wounds from WT and PRCPgt/gt mice were imaged at D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8. Each unit on the ruler equals 1 mm in length. External wound images were obtained using a Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope (original magnification ×1). (B) Wound lengths are expressed relative to D0 length (n = 10 in both groups). On 2-way analysis of variance, the PRCPgt/gt wounds closed significantly slower (P < .047). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides from D5 wounds of WT and PRCPgt/gt (gt/gt) mice that were untreated or treated with ramipril (T) were analyzed for their extent of reepithelialization. The red line demarcates the total length of the original wound; the white line represents the “wound gap.” The white arrows indicate the end of the epithelial tongues of a closing wound. In photographs in which no white line is seen, the wound gap is 0 and the wound has completely reepithelialized. (D) The percent reepithelialization is shown for WT (n = 21), gt/gt (n = 6), WT-T (n = 16), and gt/gt-T (n = 13) mice. (E) Frozen sections of D2 wounds were stained with anti–Gr-1 to assess neutrophil infiltration. (F) Mean number of neutrophils as pixels/HPF, 20× on microscopy (n = 6 in both groups). (G) Frozen sections from D5 skin wounds were stained for F4/80 to assess macrophage infiltration. (H) Mean number of macrophages as pixels/HPF on microscopy (n > 8 in both groups). (I) CD31 staining on frozen sections from D5 wounds in WT, gt/gt, WT-T, and gt/gt-T were obtained. (J) The area of CD31 staining in the 4 groups of animals was compared by morphometric analysis using the National Institutes of Health’s ImageJ software (n ≥ 5 in all groups). Fluorescent wound images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope with a 20×/0.45 for Matrigel plug images. The following in the figure indicate group paired Student t-test P values: *P < .05, ***P < .001.

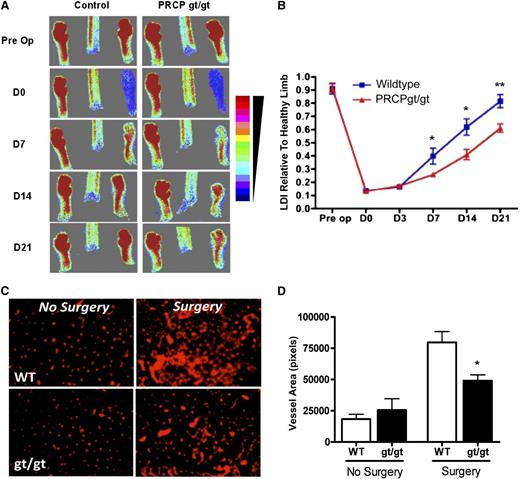

Limb ischemia recovery in PRCPgt/gt mice

The angiogenic repair defect in PRCPgt/gt mice was examined in a hind-limb ischemia model. After ligation of the femoral artery, laser Doppler imaging (LDI) of mouse feet indicated absent flow on day 0 (D0) and return of flow on D7 (Figure 4A). However, the imaged returned flow on D7, D14, and D21 was reduced in PRCPgt/gt vs WT (control) mice (Figure 4A). Beginning at D7 after the surgery through D21, PRCPgt/gt limbs had decreased rates of flow recovery (0.61 ± 0.10 flow relative to uninjured limb) compared with WT limbs (0.82 ± 0.16 relative flow) (Figure 4B). In addition, gastrocnemius muscle biopsies of injured hind limbs 28 days after surgery showed decreased PECAM immunofluorescence in PRCPgt/gt biopsies (49 031 ± 9373 pixels) compared with WT (79 692 ± 8688 pixels) (Figure 4D). Uninjured muscle showed no difference in PECAM expression (Figure 4C-D).

PRCP influences limb ischemia recovery. (A) LDI was performed on hind limbs and feet from WT and PRCPgt/gt mice (n = 10 for both groups) before and after ligation of the femoral artery on D0, D7, D14, and D21. The figure is a representative study. The scale of color from red to blue on the right represents the intensity of heat from strong to little. (B) LDI densities of the blood flow in injured limbs were compared with the uninjured limbs for each genotype on each day. On 2-way analysis of variance, the differences between the 2 recovery curves were highly significant (P < .0001). (C) Frozen sections from gastrocnemius muscles were stained with a PECAM (CD31) antibody from uninjured and ischemic limbs after the ligated vessel was excised and removed (n = 4 for both groups) 28 days after injury. Images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope 20×/0.45. (D) CD31-positive vessel area in pixels was determined by morphometric analysis in each of the control or treatment groups. *P < .05, **P < .01 for specific comparison between groups.

PRCP influences limb ischemia recovery. (A) LDI was performed on hind limbs and feet from WT and PRCPgt/gt mice (n = 10 for both groups) before and after ligation of the femoral artery on D0, D7, D14, and D21. The figure is a representative study. The scale of color from red to blue on the right represents the intensity of heat from strong to little. (B) LDI densities of the blood flow in injured limbs were compared with the uninjured limbs for each genotype on each day. On 2-way analysis of variance, the differences between the 2 recovery curves were highly significant (P < .0001). (C) Frozen sections from gastrocnemius muscles were stained with a PECAM (CD31) antibody from uninjured and ischemic limbs after the ligated vessel was excised and removed (n = 4 for both groups) 28 days after injury. Images were obtained using a Nikon TE200 microscope 20×/0.45. (D) CD31-positive vessel area in pixels was determined by morphometric analysis in each of the control or treatment groups. *P < .05, **P < .01 for specific comparison between groups.

Femoral artery wire injury in PRCPgt/gt mice

Wire injury results in endothelial cell denudation, leukocyte accumulation with smooth muscle cell proliferation, and migration and extracellular matrix deposition, producing neointimal hyperplasia.27 This process is dampened by reendothelialization, interruption of leukocyte recruitment, or inhibition of smooth muscle proliferation. Because PRCP influences endothelial cell migration, we postulated that it modulates neointimal formation after wire-induced endothelial denudation. At 14 days after wire injury, there was a significant increase in the intima between the WT (11 040 ± 10 550 μm2) and PRCPgt/gt (31 790 ± 43 670 μm2) injured vessels (P < .01) (Figure 5A and Table 1). The intima area:media area ratio (I:M) was increased in PRCPgt/gt (0.77 ± 0.92) compared with WT (0.25 ± 0.20, P < .001) mice (Figure 5B and Table 1). To probe possible mechanism(s) for enhanced neointimal thickening, we examined leukocyte (CD45-positive cells) accumulation and cellular proliferation (Ki67-positive cells). PRCPgt/gt femoral artery sections had significantly (P < .01) more leukocyte accumulation in the intima (39.6 ± 19% CD45-positive cells) and media (50.9 ± 28.6%) compared with WT intima (9.0 ± 4.1%) and media (7.7 + 8.2%) (Figure 5C and Table 1). Furthermore, cellular proliferation was increased in the intima (68.1 ± 18.2% Ki67-positive cells) and media (56.4 ± 29.6%) of PRCPgt/gt femoral arteries compared with WT intima (24.0 ± 16.7%) and media (11.0 ± 14.6%) (Figure 5D and Table 1). These studies indicate that PRCP deficiency is associated with neointimal thickening, enhanced leukocyte accumulation, and cellular proliferation after arterial injury.

PRCP and vascular injury and repair. (A) Representative photomicrographs of injured femoral arteries from WT (n = 40 arteries), PRCPgt/gt (n = 45), or combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− (n = 23) mice stained for elastin 14 days after wire injury. (B) Quantitative morphometric analysis of intima:media area ratio in WT, PRCPgt/gt, and combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− arteries. Data represent individual artery analysis for 23 to 45 animals per group. *P < .05, ***P < .001 on a 1-way analysis of variance. Representative immunohistochemical photomicrographs assessing leukocyte accumulation (CD45-positive cells [C]) and cellular proliferation (Ki67-positive cells [D]) 14 days after wire injury in WT, PRCPgt/gt, or combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− mice. All images were obtained using a Leica DM 2000 microscope with a 40×/0.65 objective lens. The sizing bar included in each image indicates 50 μm.

PRCP and vascular injury and repair. (A) Representative photomicrographs of injured femoral arteries from WT (n = 40 arteries), PRCPgt/gt (n = 45), or combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− (n = 23) mice stained for elastin 14 days after wire injury. (B) Quantitative morphometric analysis of intima:media area ratio in WT, PRCPgt/gt, and combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− arteries. Data represent individual artery analysis for 23 to 45 animals per group. *P < .05, ***P < .001 on a 1-way analysis of variance. Representative immunohistochemical photomicrographs assessing leukocyte accumulation (CD45-positive cells [C]) and cellular proliferation (Ki67-positive cells [D]) 14 days after wire injury in WT, PRCPgt/gt, or combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− mice. All images were obtained using a Leica DM 2000 microscope with a 40×/0.65 objective lens. The sizing bar included in each image indicates 50 μm.

Quantification of wire injury recovery

| . | . | Genotype . | P value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter . | . | WT . | PRCPgt/gt . | DKO . | WT vs PRCPgt/gt . | PRCPgt/gt vs DKO . | WT vs DKO . |

| Thickness | Media (μm2) | 43 710 ± 13 280 (n = 40) | 39 380 ± 17 600 (n = 45) | 43 510 ± 16 330 (n = 23) | ns | ns | ns |

| Intima (μm2) | 11 040 ± 10 550 (n = 40) | 31 790 ± 43 670 (n = 45) | 15 320 ± 12 540 (n = 23) | * | ns | ns | |

| Int./Med (ratio) | 0.25 ± 0.20 (n = 40) | 0.77 ± 0.92 (n = 45) | 0.33 ± 0.26 (n = 23) | † | ‡ | ns | |

| CD45 (% area) | Intima | 9.0 ± 4.1 (n = 6) | 39.6 ± 19.0 (n = 6) | 22.1 ± 19.9 (n = 6) | * | ns | ns |

| Media | 7.7 ± 8.2 (n = 6) | 50.9 ± 28.6 (n = 6) | 15.5 ± 16.3 (n = 6) | * | ‡ | ns | |

| Ki-67 | Intima | 24.0 ± 16.7 (n = 5) | 68.1 ± 18.2 (n = 4) | 31.4 ± 18.1 (n = 5) | * | ‡ | ns |

| Media | 11.0 ± 14.6 (n = 5) | 56.4 ± 29.6 (n = 4) | 15.9 ± 5.3 (n = 5) | * | ‡ | ns | |

| . | . | Genotype . | P value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter . | . | WT . | PRCPgt/gt . | DKO . | WT vs PRCPgt/gt . | PRCPgt/gt vs DKO . | WT vs DKO . |

| Thickness | Media (μm2) | 43 710 ± 13 280 (n = 40) | 39 380 ± 17 600 (n = 45) | 43 510 ± 16 330 (n = 23) | ns | ns | ns |

| Intima (μm2) | 11 040 ± 10 550 (n = 40) | 31 790 ± 43 670 (n = 45) | 15 320 ± 12 540 (n = 23) | * | ns | ns | |

| Int./Med (ratio) | 0.25 ± 0.20 (n = 40) | 0.77 ± 0.92 (n = 45) | 0.33 ± 0.26 (n = 23) | † | ‡ | ns | |

| CD45 (% area) | Intima | 9.0 ± 4.1 (n = 6) | 39.6 ± 19.0 (n = 6) | 22.1 ± 19.9 (n = 6) | * | ns | ns |

| Media | 7.7 ± 8.2 (n = 6) | 50.9 ± 28.6 (n = 6) | 15.5 ± 16.3 (n = 6) | * | ‡ | ns | |

| Ki-67 | Intima | 24.0 ± 16.7 (n = 5) | 68.1 ± 18.2 (n = 4) | 31.4 ± 18.1 (n = 5) | * | ‡ | ns |

| Media | 11.0 ± 14.6 (n = 5) | 56.4 ± 29.6 (n = 4) | 15.9 ± 5.3 (n = 5) | * | ‡ | ns | |

P values for one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction.

DKO, PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/−; ns, not significant, P > .05.

*P < .01.

P < .001.

P < .05.

Individual mRNA studies showed that PRCP deficiency is associated with a 1.5-fold increased expression of renal myeloid–related protein-14 (MRP-14 or S100A9), a member of the alarmin family in leukocytes, endothelial cells, and platelets (supplemental Figure 2). We have shown previously that deficiency of MRP-14 attenuated neointimal formation after wire injury.20 Therefore, we mated PRCPgt/gt mice with MRP-14–deficient (MRP-14−/−) mice and examined the effect of combined deficiency on the repair response after vascular injury. The increased I:M ratio in PRCPgt/gt (0.77 ± 0.92) mice was restored to WT levels (0.25 ± 0.20) in PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− mice (0.33 ± 0.2) (P = n.s.) (Figure 5A-B and Table 1). In addition, enhanced leukocyte accumulation (WT vs PRCPgt/gt, P < .01) and cellular proliferation (WT vs PRCPgt/gt, P < .01) in PRCPgt/gt mice were restored to WT levels in PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− mice (P = n.s.) for both (Figure 5C-D and Table 1). Taken together, these data indicate that MRP-14 deletion protected PRCPgt/gt from increased inflammation and cellular proliferation after arterial injury.

Discussion

These investigations indicate that PRCP, in addition to being a carboxypeptidase and a modulator of blood pressure and thrombosis risk, regulates cell growth and angiogenesis. The influence of PRCP on lowering blood pressure, reduction in thrombosis propensity, and vascular growth and repair after injuries suggests that it promotes vascular health. Several in vitro and in vivo experiments support this assessment. In vitro, PRCP levels correlate with cell number and proliferation as demonstrated by both siRNA knockdowns of bovine PRCP (Figure 1A-B,J) and overexpression of human PRCP (Figure 1E-F). When PRCP is depleted, there is increased Annexin V binding to the surface of cells, suggesting that its loss contributes to proapoptotic signaling.28 These findings are consistent with those of Duan et al, who showed that PRCP overexpression increased breast cancer cell proliferation and autophagy, and PRCP depletion decreased both.22 Duan et al also showed that treatment of MCF7 cells with the S28 protease class inhibitor Z-Pro-Prolinal reduced cell proliferation, suggesting that PRCP’s enzymatic activity influenced cell proliferation.22 Alternatively, we were unable to detect any influence of membrane-formed BK or exogenously added BK, Ang II, or Ang-(1-7), substrates and products of PRCP enzymatic activity on cell proliferation. Because Z-Pro-Prolinal is not specific for PRCP, we determined whether mutagenized cDNA of PRCP at codons for 2 active site amino acids of PRCP would support cell proliferation.29 To our surprise, point mutations that alter 2 critical active site amino acids of PRCP (S179A and H455A) do not block the ability of transfected cDNA (hPRCPmut) to increase cell growth (Figure 1I) or rescue the cell growth defect induced by PRCP siRNA (Figure 1J). These observations indicate that the enzymatic activity of PRCP is not required for its influence on cell proliferation. These data suggest that there is a region on PRCP independent of its active site that has growth factor activity. PRCP contains a unique region called the SKS domain whose function is presently unknown.30

Because PRCP depletion reduces cell proliferation, we examined whether it influenced in vitro cell migration and angiogenesis assays. PRCP-depleted BAEC have reduced migration after scratch injury, and aortic segments have reduced sprouting. The ex vivo sprouting assay is believed to accurately represent in vivo angiogenesis because of the presence of nonendothelial support cells and the availability of endothelial cells that have not gone through multiple passages.31 In PRCPgt/gt mice, Matrigel plugs also have less new vessel formation by hemoglobin determination than plugs from WT mice. When PECAM expression was examined on Matrigel plug sections, PRCPgt/gt vessels covered a smaller area. In addition, we observed decreased NG2 antigen expression in PRCPgt/gt Matrigel plugs, suggesting reduced VSMC growth as well. NG2 is an epitope on chondroitin sulfate 4 that is expressed exclusively on VSMCs.23,24 Furthermore, PRCPgt/gt plugs have a reduced ratio of NG2/PECAM, suggesting a greater defect in the ability of VSMCs to participate in the neoangiogenic process. These observations are consistent with the findings of Javerzat et al that PRCP contributes to the neoangiogenic process in the CAM assay.19 These abnormalities translate into slower wound repair angiogenesis (Figure 3) and less ischemic injury repair (Figure 4).

Several in vivo angiogenesis assays were performed on PRCPgt/gt mice. PRCPgt/gt mice have delayed wound closure and reepithelialization after injury (Figures 3A,D). Remarkably, wound healing in PRCPgt/gt mice is corrected by prior in vivo treatment with an ACE inhibitor. The wound closure defect in PRCPgt/gt mice is not caused by initial altered leukocyte infiltration because on D2 there was no difference between WT and genetrap mice in neutrophil or macrophage infiltration (Figure 3E-F). However, on D5, there is an increase in F4/80 macrophages into the wound (Figure 3G-H). This latter finding is consistent with the observation that D14 wire-injured vessels have increased leukocyte infiltration in the PRCPgt/gt mice (discussed next). The finding that endothelial PRCP is upregulated by lipopolysaccharide treatment suggests the protein contributes to repair inflammation.32 The observation that the delay in wound closure becomes apparent on D5 is consistent with the observation that there is an angiogenesis defect in PRCPgt/gt mice (Figure 3I-J). This finding is consistent with other studies that show the invasive blood vessel repair process begins around D4 to D6 in full-thickness wound models.33 Because PRCP has an antioxidant role in endothelium, it may modulate inflammation by regulating reactive oxygen species.1,33 Again it was an unexpected finding to observe that prior ACE inhibitor therapy corrects both wound closure and the angiogenesis defect in PRCPgt/gt mice (Figure 3I-J). ACE inhibitors are recognized to protect from collagen remodeling and promote angiogenesis after cardiac ischemia.34,35 It is of interest that in vitro peptide substrates or products of ACE do not influence cell growth, but in vivo use of ACE inhibitors promotes wound reepithelialization and angiogenesis. Recent investigations suggest that signaling cascades leading to cell growth and angiogenesis may differ.36

PRCP deficiency also influences the repair of large vessels. Tissue ischemia after large-vessel occlusion induces angiogenesis by redirecting blood flow to smaller proximal arterioles.37 Using a hind limb ischemia model, the recovery of blood flow after femoral artery ligation was slowed in PRCPgt/gt compared with WT mice (Figure 4A-B) as measured by LDI of global limb recovery. To assess ischemia-induced angiogenesis in muscle, gastrocnemius muscle biopsies from PRCPgt/gt mice with the femoral artery ligated and excised are found to have decreased PECAM-stained vessel area in frozen muscle sections (Figure 4C-D). This method measures reduced ischemia-induced angiogenesis in the smaller vessels of the gastrocnemius that are sufficiently deep into the limb so as not to be detected by LDI.38 Thus, both large and small arterial vessel angiogenesis is impaired in PRCP-deficient mice.

PRCP not only modulates angiogenesis but also the biological response to endothelial-denuding arterial injury as evidenced by increased neointimal formation after wire injury. However, the precise mechanisms of PRCP action are uncertain. We speculate that increased neointimal hyperplasia in PRCP-deficient mice arises from delayed reendothelialization and/or increased VSMC proliferation. PRCP depletion is associated with transcriptional downregulation of eNOS and uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide production, thereby promoting VSMC proliferation as a consequence of reduced cGMP production.1,39,40 However, because PRCP is expressed in both endothelial cells and VSMCs in large arteries, a direct effect of VSMC PRCP on neointimal formation cannot be excluded.1 Finally, vascular inflammation is central to the repair response after injury,27 and there is compelling evidence that targeting inflammation significantly attenuates neointimal thickening.27,41 Indeed, restoration of enhanced neointimal formation and leukocyte accumulation in PRCPgt/gt mice to WT levels in combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− mice strongly suggests a pathophysiological role for vascular inflammation, and MRP-14 (S100A9) in particular.

The S100-family is comprised of 21 unique proteins that are typically small (∼9-14 kDa) and contain 2 Ca2+-binding EF hand domains. MRP-14 and MRP-8 are recognized among a subgroup of S100 proteins to be associated with acute and chronic inflammatory disorders. MRP-14 and MRP-8 (S100A/8) are expressed by polymorphonuclear neutrophils and monocytes,42,43 and there is evidence from our laboratory and others that platelets express both MRP-14 and MRP-8.44,45 Emerging evidence from studies using cells from MRP-14−/− mice suggests that MRP-14 regulates leukocyte migration.46 In vitro studies with MRP-14−/− polymorphonuclear neutrophils show markedly diminished migration through endothelial monolayers and attenuated chemokinesis in a 3-dimensional collagen matrix.47 Studies in our laboratory using MRP-14−/− mice determined that MRP-8/14 broadly regulates vascular inflammation and contributes to the biological response to vascular injury in models of atherosclerosis, restenosis, and vasculitis by promoting leukocyte recruitment.20 Interestingly, deficiency of PRCP is associated with a 1.5-fold increase in the expression of MRP-14. The regulation of MRP-14 by PRCP is therefore of significant interest.

In conclusion, our studies indicate an important role for PRCP in the maintenance of vascular homeostasis. Prior investigations indicate that PRCPgt/gt mice are hypertensive and prothrombotic.1 The present study indicates that depletion of PRCP also impairs angiogenesis and wound healing as a likely consequence of its effects on endothelial cell proliferation and migration. The profound effect of PRCP deficiency on neointimal formation after mechanical arterial injury and its protection by MRP-14 depletion further raises the possibility that PRCP regulates neointimal formation and suppression of the inflammatory response. The mechanism of PRCP on cell growth and efforts to enhance PRCP expression to promote antiinflammatory, antiproliferative, and antithrombotic effects are the focus of ongoing investigations.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Aaron Proweller of Case Western Reserve University for his helpful discussions about some of these studies.

This work was supported by grants HL052779-16 and HL112666 (A.H.S.), HL85816 and HL57506 Merit Award (D.I.S.), and HL110630, HL076754, HL097593, HL112486, and HL088548 (M.K.J.).

Authorship

Contribution: G.N.A., E.X.S., C.F., A.M., M.A.A., K.N., T.M., S.M., and G.A.L. performed experiments; G.N.A., E.X.S., C.F., A.M., M.A.A., M.K.J., D.I.S., and A.H.S. conceptualized and planned experiments; G.N.A., E.X.S., and A.H.S. prepared the figures; and G.N.A., E.X.S., D.I.S., and A.H.S. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alvin H. Schmaier, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Ave, WRB2-130, Cleveland, OH 44106-7284; e-mail: schmaier@case.edu.

![Figure 5. PRCP and vascular injury and repair. (A) Representative photomicrographs of injured femoral arteries from WT (n = 40 arteries), PRCPgt/gt (n = 45), or combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− (n = 23) mice stained for elastin 14 days after wire injury. (B) Quantitative morphometric analysis of intima:media area ratio in WT, PRCPgt/gt, and combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− arteries. Data represent individual artery analysis for 23 to 45 animals per group. *P < .05, ***P < .001 on a 1-way analysis of variance. Representative immunohistochemical photomicrographs assessing leukocyte accumulation (CD45-positive cells [C]) and cellular proliferation (Ki67-positive cells [D]) 14 days after wire injury in WT, PRCPgt/gt, or combined PRCPgt/gt/MRP-14−/− mice. All images were obtained using a Leica DM 2000 microscope with a 40×/0.65 objective lens. The sizing bar included in each image indicates 50 μm.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/122/8/10.1182_blood-2012-10-460360/4/m_1522f5.jpeg?Expires=1769093833&Signature=N0Sb9J6mhXClbLi~2WAusnhgBhtnDDhJVPbJuuz~38Mjqk1zQ0IiIJNnCa-i9YiNq~-1PaIKVCaf3cpnIMHZG6ToFrS5jEsDY6RGgv2Lpqozh2o3Y0KtukcvsLVy7TxhG6ET~N665P93fBWVqNH9ox6Q7kNMpHB1QbIBSnBaUOFlVfLTA1CF0-c~wqMTH2q~RBbsdHmzwAwvribkCy14j5ZhIwe01ZTDj4XoQG7HkrjFG5Ns5b6vK1c0Lc9Fgo-J5kN7PykXDb-LDYKg~nN0IqqqHFPxPqq40mgfElmDy3XwmnbpsrVy1qEwkJbrgv-ulR5H3qx7ysqERlaMWOvtqg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)