In this issue of Blood, Kassebaum et al estimate that the global anemia prevalence in 2010 was 32.9%, resulting in 68.4 million years lived with disability (YLD).1 The results emphasize the important contribution made by anemia to the overall global burden of disease and should help focus attention and resources toward this problem.

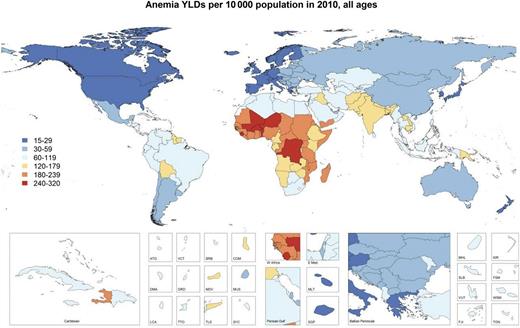

Total YLD due to anemia in 2010, by country. Anemia makes important contributions to disease burden in most low- and middle-income countries. The burden of anemia remains highest in sub-Saharan Africa, with South Asia also heavily affected.

Total YLD due to anemia in 2010, by country. Anemia makes important contributions to disease burden in most low- and middle-income countries. The burden of anemia remains highest in sub-Saharan Africa, with South Asia also heavily affected.

Several previous efforts have summarized the global prevalence and impact of anemia. In 1985, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that about 30% of the world population was anemic.2 In 1992, the WHO estimated that 37% of all women were anemic.3 A 2008 WHO analysis reported that anemia affected 24.8% of the world’s population, including 42% of pregnant women, 30% of nonpregnant women, and 47% of preschool children.4 Most recently, global anemia prevalence was estimated at 29% in pregnant women, 38% in nonpregnant women, and 43% in children, with reductions since 1995 in each group.5 The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2000 report estimated that anemia accounted for 2% of all YLD and 1% of disability-adjusted life-years6 ; the GBD 2004 update had similar findings.7

Kassebaum et al have furthered these analyses to provide detailed estimates of the prevalence and epidemiology of anemia, its impacts on global health (see figure), and its key determinants, stratified by age and sex, and compared these between 1990 and 2010. To achieve this, the authors used data from 409 data sets from the Demographic and Health Surveys (which are national, weighted surveys of health status, with anemia measured by capillary hemoglobin) and WHO databases that contain data from national and subnational epidemiologic surveys. The 17 specific causes that contribute to anemia were then apportioned by using data from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors 2010 (GBD 2010) study, with residual prevalence after attribution assigned to other causes, including iron deficiency anemia.

Next, the authors estimated the impact of anemia on global health (disease burden). To appreciate disease burden estimates, it is worth looking under the hood at their calculation. The first concept is the disability weight (DW), a value representing the severity of health loss associated with a clinical condition. Previous DW estimations were criticized for being determined by expert committees; thus, for GBD 2010, DWs were developed by opinion from the general public through a comprehensive international study (30 230 participants) comprising household surveys in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Peru, Tanzania, and the United States, together with an open-access Internet survey.8 Participants were given descriptions of 2 hypothetical patients with particular health states and asked which individual they considered healthier. The Internet survey also asked respondents to compare the value of various life-saving or disease prevention programs. Thus, 220 health conditions (including mild, moderate, and severe anemia) were ranked, and DWs were assigned (with 0 for the mildest and 1 for the equivalent of death). Mild anemia was the third mildest of all conditions (DW of 0.005, more serious only than “mild impairment in distance vision” and “treated, long-term fractures”), whereas moderate and severe anemia had DWs of 0.058 (similar to “moderate hearing loss with ringing”) and 0.164 (similar to “amputation of one leg, long term”). The DWs for mild, moderate, and severe anemia were each higher in GBD 2010 than in the previous report (GBD 2004).8 The YLD, an estimate of the total number of years lived in less-than-ideal health due to a condition, is calculated by multiplying its prevalence by its DW, and this figure estimates the burden of each disease.9

By using this approach, the authors found that anemia accounts for 8.8% of the world’s YLD, but that the prevalence of anemia worldwide has decreased from 1990 to 2010, with most of the improvement coming from a genuine reduction in the conditions that cause anemia. This raises an important research question: What combination of improvements in proximal and distal determinants of anemia have effected this change? Children younger than age 5 years still have the highest prevalence of, and the most severe, anemia and had rising prevalence in contrast to the overall trend and findings from other reports.5 South Asia accounted for 37.5% of the global anemia burden, whereas sub-Saharan Africa contributed 23.9%. The main causes of anemia worldwide were attributable to 3 syndromes: iron deficiency (iron deficiency anemia, hookworm, and schistosomiasis), hemoglobinopathy (sickle cell disorders and thalassemia), and malaria. Coexistence of iron deficiency and malaria as top causes of anemia in sub-Saharan Africa highlight the paradox for anemia control in such regions, insofar as iron supplementation might increase malaria risk. Another important finding of this study is the increasing contribution from chronic kidney disease, which increased over the 2 decades of the study and is the chief cause of anemia in the 80+ age group. Readers should note that the supplemental material for Kassebaum et al1 contains many of the key results: supplemental Figure 9 depicts the proportion of anemia attributable to each cause, by age, and supplemental Table 7 is a summary of the prevalence of anemia in each of 187 countries.

WHO10 and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define anemia in children younger than age 5 years as hemoglobin <110g/L. However, the authors defined anemia in this age group as hemoglobin <120g/L, and they acknowledge that this has inflated estimates of the prevalence of anemia in children in this age group by 16.3% in males and 18.1% in females, on average, although by even more in some cases. This should be borne in mind when interpreting estimates of prevalence and burden of anemia in this age group.

Although founded in data, this report presents modeling-based estimates of the determinants of anemia and does not replace the need for field epidemiology to measure the contributions to anemia of factors such as iron, folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin A deficiencies; hemoglobinopathy; malaria; inflammation; and other causes in specific settings; such studies are rare outside (and even within) developed nations.

Nevertheless, Kassebaum et al1 have developed a valuable resource that confirms the significance of anemia within the overall context of global health, provides the first global estimates of its causes, and thus will be essential in guiding future control strategies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.