Key Points

Plasminogen influences uptake of apoptotic bodies and immunoglobulin-coated red cells by macrophages in mice.

Plasminogen regulates expression of genes involved in macrophage phagocytosis in vivo.

The phagocytic function of macrophages plays a pivotal role in eliminating apoptotic cells and invading pathogens. Evidence implicating plasminogen (Plg), the zymogen of plasmin, in phagocytosis is extremely limited with the most recent in vitro study showing that plasmin acts on prey cells rather than on macrophages. Here, we use apoptotic thymocytes and immunoglobulin opsonized bodies to show that Plg exerts a profound effect on macrophage-mediated phagocytosis in vitro and in vivo. Plg enhanced the uptake of these prey by J774A.1 macrophage-like cells by 3.5- to fivefold Plg receptors and plasmin proteolytic activity were required for phagocytosis of both preys. Compared with Plg+/+ mice, Plg−/− mice exhibited a 60% delay in clearance of apoptotic thymocytes by spleen and an 85% reduction in uptake by peritoneal macrophages. Phagocytosis of antibody-mediated erythrocyte clearance by liver Kupffer cells was reduced by 90% in Plg−/− mice compared with Plg+/+ mice. A gene array of splenic and hepatic tissues from Plg−/− and Plg+/+ mice showed downregulation of numerous genes in Plg−/− mice involved in phagocytosis and regulation of phagocytic gene expression was confirmed in macrophage-like cells. Thus, Plg may play an important role in innate immunity by changing expression of genes that contribute to phagocytosis.

Introduction

Phagocytosis is the process by which invading pathogens or unwanted cells are efficiently removed from organs by professional phagocytes, primarily macrophages. The phagocytic process can be dissected into several distinct steps, which begins with the release of “find me” signals from “prey bodies” leading to chemotaxis of phagocytes. The “find me” step is followed by engagement of “eat me” signals that allows for recognition of prey bodies by phagocytes bearing appropriate receptors. This step is followed by engulfment and processing of prey bodies. Defects in any step can perturb tissue homeostasis and lead to autoimmune diseases or excessive pathogenic burdens.1,-3 The “eat me” signals on apoptotic prey bodies include externalized phosphatidylserine or coated serum proteins (eg, thrombospondin, complement C1q, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein).2 These signals can be recognized by various phagocytic receptors on macrophages. To facilitate recognition by macrophages, invading pathogens often become opsonized by immunoglobulins (IgG) and complement.1 The opsonized pathogens are then recognized by Fc γ receptors or complement receptors on macrophages, which mediate internalization.

Phagocytic recognition leads to Rac-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement, which facilitates engulfment of prey bodies. A change in intracellular signals upon phagocytic recognition also generates inflammatory cytokines.1,2 The resultant phagosomes that form inside the macrophages undergo maturation and fusion with acidic lysosomes, a process that requires activation of Rab family proteins. Ultimately, phagocytosed materials are digested by acidic proteases and nucleases inside the phagosomes into nucleotides, fats or amino acids that are used inside the cell or are excreted.1,2

Plasminogen (Plg), the zymogen of the serine protease plasmin, binds to cell surfaces and extracellular matrix proteins and facilitates fibrinolysis, wound healing, inflammatory cell recruitment and growth factor and hormone processing.4,5 On cell surfaces, Plg interacts with multiple receptors which bear or mimic C-terminal lysines and interact with the kringle domains of Plg.6 Plg binding to macrophages enhances plasmin formation and generates intracellular signals that modulate gene expression7,8 and functional responses such as foam cell formation.9

Although there is extensive data implicating Plg in macrophage function, only limited evidence suggests its role in phagocytosis. Two recent studies point in this direction. Kawao et al10 compared healing following liver injury in Plg−/−, uPA−/− and wild-type (WT) mice and concluded that Plg was important for macrophage phagocytosis of cellular debris. Rosenwald et al11 isolated Plg as a serum factor that enhanced phagocytosis and concluded that it operated by affecting prey cells and not the phagocytic function of the macrophages. In the present study, we provide direct evidence that Plg does indeed affect the phagocytosis but has a profound effect on the phagocytic activity of the macrophage per se. Evidence for this function of Plg is demonstrated in mouse models representing 2 major challenges to macrophage phagocytosis. This study also provides clear evidence that Plg governs changes in gene expression that occur in macrophages during phagocytosis. Thus, our study identifies new roles of Plg in macrophage biology.

Materials and methods

Mice, cells, and cell treatments

All animal experiments were performed under institutionally approved protocols.

Male and female Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice in a C57BL/6J background (crossed into this background for at least 10 generations) were obtained from crosses of Plg+/− mice. The mice used in experiments were 8 to10 weeks of age. J774A.1 cells, a murine macrophage-like cell line, were obtained from ATCC and maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM l-glutamine, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 4.5g/L glucose and 1mM sodium pyruvate. For experiments, the J774A.1 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 1% Nutridoma (Roche) and either pretreated with 200 μM tranexamic acid (TXA; Sigma-Aldrich) or 20 nM D-Val-Phe-Lys chloromethylketone dihydrochloride (plasmin inhibitor [PI]; EMD Millipore) and then treated with human Glu-Plg (1 μM; Enzyme Research Laboratories). This concentration of Plg was used throughout the experiments shown, but its phagocytic function with J77A.1 cells could be detected at concentrations as low as 2 nM.

Thymocytes preparation, labeling, and apoptosis

Thymocytes were isolated from the thymus of 8-week-old Plg+/− mice using established protocols.12 The procedure is elaborated in supplemental Methods (available at the Blood Web site).

Preparation of IgG-coated beads

Sulfated fluorescent microspheres (Yellow/Green: 505/515 nm), 2.0 μm diameter (Invitrogen), were coated with mouse IgG13 as elaborated in supplemental Methods).

In vitro phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes

This assay was performed as described.13 J774A.1 (0.2 × 106) cells were cultured on glass coverslips in 24-well plates. The cells were treated with Plg, with or without inhibitors, for 24 hours. The treated cells were then washed and fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes were added at a ratio of 5:1 (prey: phagocytes) for 90 minutes at 37°C in 1% Nutridoma/DMEM. Cells were washed 5 times with ice cold PBS and stained with 7.5 μg/mL Cell Mask plasma membrane stain (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies) for 10 minutes prior to fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. Coverslips were then mounted using Vectashield mounting medium with 4′, 6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories) and imaged using Leica TCS-SP2-AOBS laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). All images were quantified using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics) to measure area of green fluorescence per nucleus.

Immunoglobulin-mediated phagocytosis in vitro

J774A.1 (0.2 × 106) cells were seeded onto glass coverslips in 24-well plates and treated with Plg, with or without inhibitors, for 24 hours. Cells were then washed and incubated with 2.5 µL of IgG-coated fluorescent bead suspension for 90 minutes at 37°C in 1% Nutridoma/DMEM. Free beads were removed by washing 5 times with ice-cold PBS, followed by fixation of the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then subjected to plasma membrane stain using anti-CD45 (BD Biosciences) followed by Alexa flour 568 anti-rat IgG. Coverslips were then processed and analyzed as described for apoptotic thymocytes.

In vivo phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes

Preparations of 5 × 107 fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes were injected into the tail veins of mice.14 Mice were killed 1 hour after injection, and the spleens and livers were harvested. To assess phagocytosis, 5-μm cryosections of spleen were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature and then mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) containing 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole. Images were taken at ×20 magnification with an upright fluorescence microscope, and area of green fluorescence per field was quantified using Image-Pro Plus. In a second model using apoptotic thymocytes, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 2 × 107 fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes.15 After 30 minutes, the mice were killed and resident peritoneal cells and uncleared apoptotic cells were collected by lavage. Cells were analyzed by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) using CellQuest Software to detect fluorescence intensity.

In vivo phagocytosis of immunoglobulin-opsonized bodies

A model of experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia involving phagocytosis of antibody-coated red blood cells (RBC) was used.16,-18 Anti-mouse RBC mAb34-3C (100 μg; Hycult Biotech) was injected intraperitoneally into 8 week old mice. After 3 days, the livers were harvested, fixed in histochoice and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Prussian blue. Blood was collected in heparinized hematocrit tubes, centrifuged in Autocrit Ultra 3 for 5 minutes to measure RBC levels, and the anemia was measured from the calculated hematocrits. Paraffin sections (5-μm thickness) of livers were processed and stained for iron deposits using Prussian blue as follows. Slides were deparaffinized, and treated with an aqueous mixture of equal parts of 20% hydrochloric acid and 10% potassium ferrocyanide for 20 minutes, washed in distilled water, dehydrated and mounted with Cytoseal-60 (Thermo Scientific). Images were taken at ×20 magnification and area of blue per field was quantified as iron deposits using Image-Pro Plus.

Phagocytosis gene array

Spleen and liver tissues (n = 3) were homogenized in RLT buffer (Qiagen) using a rotor- stator homogenizer (Tissue ruptor; Qiagen). Total RNA was extracted using the RNEasy minikits (Qiagen). A total of 0.5 μg of RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the RT2 first strand kit (Qiagen). Quantitative PCR was then performed using the RT2 Profiler mouse phagocytosis PCR array (PAMM-173ZA-2) from Qiagen according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The same thermal profile conditions were used for all primers sets: 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. The data obtained were exported to the SABiosciences PCR array web-based template where it was analyzed using the ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analysis

To compare differences between 2 groups, an unpaired Student t test was used, and changes between multiple groups were analyzed using a 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison test. All analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 12 software. Values are expressed as mean ± SD, and P values ≤.05 were considered significant.

Additional material and methods are provided in supplemental Methods.

Results

Plg facilitates phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes and IgG-opsonized bodies in vitro

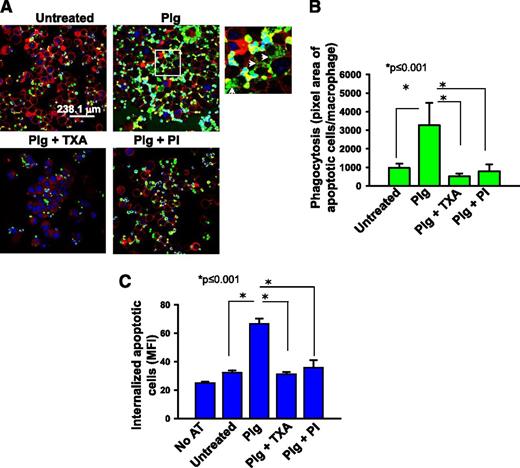

As an initial approach to assess the contribution of Plg to phagocytosis, an in vitro assay was performed using fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes as prey and J774A.1 macrophage-like cells as phagocytes. J774A.1 cells offer the advantage that cultures can be performed in the absence of serum (1% Nutridoma/DMEM); that is, essentially a purified system. Following culture under the selected treatment condition, J774A.1 cells were incubated with labeled apoptotic thymocytes, and phagocytosis was quantified as total fluorescence of labeled apoptotic bodies associated with the macrophages. Plg enhanced phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes by 3.7-fold compared with the absence of Plg (Figure 1A-B, P ≤ .001, n = 5). When cells were treated with a combination of Plg and TXA, a C-terminal lysine analog that blocks Plg binding to macrophages19 or a PI, D-Val-Phe-Lys chloromethylketone dihydrochloride, phagocytosis of the apoptotic thymocytes was inhibited significantly (Figure 1A-B, P ≤ .001). To insure that Plg enhanced internalization and not just the surface association of the apoptotic thymocytes with the J774.A1 cells, we measured the cell-associated fluorescence by flow cytometry before and after quenching with trypan blue as previously described.20 When the cell-surface associated fluorescence was eliminated by this maneuver, Plg still led to a marked induction of phagocytosis (Figure 1C, P < .001, n = 3). In the presence of TXA and PI, Plg mediated phagocytosis was reduced to basal levels (P < .001 vs Plg treated). TXA or PI did not alter the viability of the macrophages. For example, by flow cytometry, the percentage of cells double positive for annexin V and propidium iodide in the presence or absence of Plg and PI was 8.9% and 10.9%, respectively.

Plg enhances phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes by J774A.1 cells. J774A.1 cells, a murine macrophage-like cell line, were pretreated with or without Plg (1 μM for 24 hours) and then washed and incubated with fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes. In some experiments, cells were also pretreated with TXA (200 μM) or PI (20 nM) with the Plg. (A) Confocal microscopic images of J77A.1 cells with ingested apoptotic thymocytes labeled with Cell Tracker (green) dye. Images (original magnification, ×63) were captured at room temperature under Leica TCS-SP2-AOBS spectral laser scanning confocal microscope and analyzed using the Image-Pro Plus software. Plasma membrane (red) is marked with Cell Mask plasma membrane stain. The 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole stains nuclei (blue) of both macrophages and apoptotic thymocytes. A zoomed image from Plg-treated cells (white inset) shows breakdown of ingested apoptotic thymocytes (white arrows). (B) Quantification (means ± SD) of IOD of total fluorescence intensity of labeled apoptotic bodies per macrophage nucleus in a microscopic field. (C) Flow cytometry quantification of ingested apoptotic thymocytes labeled with green fluorescence in treated or untreated J774A.1 cells. Bars are ±SD of average MFI of the macrophage population as measured by flow cytometry and analyzed using CellQuest software. Prior to analysis, cell-surface fluorescence was quenched with Trypan blue. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. AT, apoptotic thymocytes; IOD, integrated optical density; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; PI, plasmin inhibitor D-Val-Phe-Lys chloromethylketone dihydrochloride.

Plg enhances phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes by J774A.1 cells. J774A.1 cells, a murine macrophage-like cell line, were pretreated with or without Plg (1 μM for 24 hours) and then washed and incubated with fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes. In some experiments, cells were also pretreated with TXA (200 μM) or PI (20 nM) with the Plg. (A) Confocal microscopic images of J77A.1 cells with ingested apoptotic thymocytes labeled with Cell Tracker (green) dye. Images (original magnification, ×63) were captured at room temperature under Leica TCS-SP2-AOBS spectral laser scanning confocal microscope and analyzed using the Image-Pro Plus software. Plasma membrane (red) is marked with Cell Mask plasma membrane stain. The 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole stains nuclei (blue) of both macrophages and apoptotic thymocytes. A zoomed image from Plg-treated cells (white inset) shows breakdown of ingested apoptotic thymocytes (white arrows). (B) Quantification (means ± SD) of IOD of total fluorescence intensity of labeled apoptotic bodies per macrophage nucleus in a microscopic field. (C) Flow cytometry quantification of ingested apoptotic thymocytes labeled with green fluorescence in treated or untreated J774A.1 cells. Bars are ±SD of average MFI of the macrophage population as measured by flow cytometry and analyzed using CellQuest software. Prior to analysis, cell-surface fluorescence was quenched with Trypan blue. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. AT, apoptotic thymocytes; IOD, integrated optical density; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; PI, plasmin inhibitor D-Val-Phe-Lys chloromethylketone dihydrochloride.

As a second model, IgG-coated fluorescent microbeads, ie, opsonized particles13 were presented to the J774.1A cells. As shown in Figure 2A-B, Plg enhanced uptake of the beads by 4.9-fold (P ≤ .03, n = 5). TXA (Figure 2A-B, P ≤ .03) and the PI were again very effective in blocking the phagocytic uptake of the IgG-coated beads (Figure 2A-B, 79.2% inhibition, P ≤ .03 vs Plg treated). When the J774A.1 cells were activated with LPS to mimic exposure to an inflammatory stimulus, the phagocytic activity of the cells for the IgG-coated microbeads increased by 4.3-fold (supplemental Figure 1A-B), and addition of Plg still further enhanced the phagocytosis (74%, P < .001 of the IgG-coated beads) by the LPS primed macrophages.

Plg promotes phagocytosis of IgG-coated microbeads by J774A.1 cells. J774A.1 macrophage-like cells were pretreated with or without Plg (1 μM) for 24 hours in the presence or absence of TXA (200 μM) or PI (20 nM). (A) Confocal microscopic images of macrophages with ingested IgG-opsonized green latex beads. Images at original magnification of ×63 were captured as in Figure 1. The plasma membrane is stained with anti-CD45 (red). The cells are counterstained with 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). (B) Quantification (means ± SD) of IOD of ingested beads per macrophage. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Plg promotes phagocytosis of IgG-coated microbeads by J774A.1 cells. J774A.1 macrophage-like cells were pretreated with or without Plg (1 μM) for 24 hours in the presence or absence of TXA (200 μM) or PI (20 nM). (A) Confocal microscopic images of macrophages with ingested IgG-opsonized green latex beads. Images at original magnification of ×63 were captured as in Figure 1. The plasma membrane is stained with anti-CD45 (red). The cells are counterstained with 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). (B) Quantification (means ± SD) of IOD of ingested beads per macrophage. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

A series of additional experiments were performed to further characterize the requirements for Plg and plasmin in macrophage phagocytic activity. (1) When J774A.1 cells were treated for 1 hour rather than 24 hours with Plg, there was no significant increase in the phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized beads compared with the absence of Plg (untreated = 425.3 ± 30 bead pixels vs 1 hour Plg treated = 522.3 ± 40 bead pixels, P = .35). (2) When J774.A1 cells were pretreated with cycloheximide for 1 hour and then treated with Plg for 24 hours, Plg failed to increase phagocytosis of opsonized IgG beads (supplemental Figure 2). These data indicate that de novo protein synthesis is required for Plg to exert its effect on macrophage-mediated phagocytosis. (3) When plasmin activity was inhibited with the PI peptide after treating the macrophages for 24 hours with Plg, the enhanced uptake of apoptotic thymocytes by J774.A1 cells was still observed (median fluorescence intensities: PI untreated, Plg untreated = 32.17; Plg treated, PI untreated = 66.7; PI treated, Plg untreated = 30.7; PI treated, Plg treated = 65.0. (4) When apoptotic thymocytes were prepared in 10% serum in the presence of PI, washed and then added to J774A.1 cells that had been treated with Plg for 24 hours, phagocytosis was decreased by 30% (P = .03) compared with apoptotic thymocytes prepared in the absence of PI. However, PI treatment of the J774.A1 cells had a much more profound effect on phagocytosis (90% inhibition, P < .001, Figure 1C).

Plg deficiency delays clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo

We sought to extend these findings to an in vivo setting. Intravenous injection of apoptotic cells leads to their accumulation in the spleen where they adhere and are then phagocytosed by macrophages that reside in the marginal zone of the tissue.14,21 Upon injection of fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes, Plg−/− mice showed a delayed clearance of apoptotic cells from the spleen compared with Plg+/+ mice (Figure 3A). Quantification of accumulated labeled bodies in the spleen showed 60% (n = 5, P = .017) higher accumulation in the Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ spleens (Figure 3B). Labeled thymocytes localized primarily in the marginal zone of the spleen in the Plg−/− mice (Figure lA). However, the number of marginal zone macrophages, identified as SIGNR1 positive cells,14 was similar in Plg−/− and Plg+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 3A-B). These data demonstrate that Plg is required for efficient phagocytic clearance of apoptotic thymocytes from the circulation by splenic macrophages.

Plg deficiency delays clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo. (A-B) Cell Tracker Green CMFDA-labeled mouse apoptotic thymocytes were injected IV into Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice. (A) Fluorescent microscopic images in duplicate (top and bottom panels are from 2 different Plg+/+ and 2 different Plg−/− mice) showing green-labeled apoptotic thymocytes trapped in the marginal zone of harvested spleens. Images with original magnification of ×20 were captured at room temperature under a Leica DMR upright microscope using an α Retiga EXi Cooled CCD camera and Image-Pro Plus software. The 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) stains nuclei of splenic cells. Images are representative of 5 Plg+/+ and 5 Plg−/− mice. (B) Quantification of apoptotic thymocytes as areas of fluorescence in the spleens of Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice. Bars are mean ± SD of average green fluorescence area per microscopic field. Three to 5 microscopic fields were counted from 5 mice per group. (C-D) Cell Tracker Green CMFDA-labeled apoptotic thymocytes were injected into the peritoneum of Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Peritoneal cells were collected 1 hour postinjection and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) A representative flow cytometry histogram comparing the fluorescence intensity of peritoneal lavage cells and showing the enhanced accumulation of thymocytes in Plg−/− mice compared with Plg+/+ mice. (D) Quantitative analysis of cells recovered from peritoneum of Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Fluorescent cells with MFI are gated and MFI values derived from these cells are used in the calculation. Bars are mean ± SD of average green fluorescence (n = 3).

Plg deficiency delays clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo. (A-B) Cell Tracker Green CMFDA-labeled mouse apoptotic thymocytes were injected IV into Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice. (A) Fluorescent microscopic images in duplicate (top and bottom panels are from 2 different Plg+/+ and 2 different Plg−/− mice) showing green-labeled apoptotic thymocytes trapped in the marginal zone of harvested spleens. Images with original magnification of ×20 were captured at room temperature under a Leica DMR upright microscope using an α Retiga EXi Cooled CCD camera and Image-Pro Plus software. The 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) stains nuclei of splenic cells. Images are representative of 5 Plg+/+ and 5 Plg−/− mice. (B) Quantification of apoptotic thymocytes as areas of fluorescence in the spleens of Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice. Bars are mean ± SD of average green fluorescence area per microscopic field. Three to 5 microscopic fields were counted from 5 mice per group. (C-D) Cell Tracker Green CMFDA-labeled apoptotic thymocytes were injected into the peritoneum of Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Peritoneal cells were collected 1 hour postinjection and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) A representative flow cytometry histogram comparing the fluorescence intensity of peritoneal lavage cells and showing the enhanced accumulation of thymocytes in Plg−/− mice compared with Plg+/+ mice. (D) Quantitative analysis of cells recovered from peritoneum of Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Fluorescent cells with MFI are gated and MFI values derived from these cells are used in the calculation. Bars are mean ± SD of average green fluorescence (n = 3).

The differences in phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo in Plg−/− mice was documented in a second experimental model in which apoptotic thymocytes were injected into the peritoneum as described.16 Plg−/− mice showed 84.8% (n = 3, P = .009) impaired clearance of the fluorescently labeled apoptotic thymocytes injected into the peritoneal cavity compared with Plg+/+ mice (Figure 3C-D). Nevertheless, the total number of resident macrophages in the 2 genotypes (Plg+/+, 2.4 × 106 ± 0.14 vs Plg−/−, 2 × 106 ± 0.21) were not different. Thus, Plg was vital to efficient removal of apoptotic cells at 2 distinct anatomic sites.

Plg deficient mice display impaired phagocytosis by liver Kupffer cells in a hemolytic anemia model

To assess if Plg influences IgG-mediated phagocytosis in vivo, we implemented an experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia model.16,18 In this model, anemia is induced by a single injection of IgG2a anti-RBC antibody. The antibody coated RBC are eliminated primarily by Kupffer cells in the liver via a FcR γ receptor mediated interaction and leads to anemia in the mice.22 The efficiency of phagocytosis of the IgG-coated RBC can be quantified by the content of iron and agglutinated RBCs in the liver Kupffer cells.16,-18 Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with either PBS or IgG2a anti-mouse RBC mAb (34-3C clone). No difference was observed in the initial hematocrits of the Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice or in the mice injected with PBS on day 3 (Figure 4A). However, on day 3 after antibody treatment, while both Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice showed a decrease in hematocrit, the decrease in the treated Plg+/+ mice was much more pronounced (57.2%, P < .001) compared with untreated Plg+/+ mice; the decrease in the treated Plg−/− mice was 30% vs untreated Plg−/− mice, P < .001. Between the antibody treated groups, Plg+/+ mice showed a 37.5% (P = .002) greater decrease in hematocrit compared with Plg−/− mice. To assess the contribution of phagocytosis to these differences in hematocrits, livers were excised and stained for iron content with Prussian blue. Liver from Plg+/+ mice showed extensive Prussian blue accumulation (90.4% more, P = .03) compared with Plg−/− mice reflecting the poor ability of the Plg−/− Kupffer cells to phagocytose the IgG-coated RBC (Figure 4B-C). This staining result reflected the differences in the hematocrits of the mice (Figure 4A). H&E staining of liver showed extramedullary hematopoietic foci, a typical response to anemia, and agglutinated RBCs in Plg+/+ liver (Figure 4B) but these deposits were rare in Plg−/− liver. Plg+/+ mice liver showed 90.5% more (P = .004) agglutinated RBCs compared Plg−/− (Figure 4B,D). Nevertheless, the numbers of liver Kupffer cells in the 2 genotypes were similar as revealed by staining with the macrophage-specific anti-F4/80 antibody23 (supplemental Figure 4A-B).

Plg deficiency diminishes IgG-mediated erythrocyte phagocytosis in vivo.Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-mouse RBC mAb 34-3C to induce experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia. (A) Hematocrits in mice 3 days after injection of PBS or anti-RBC mAb 34-3C. Bars are mean ± SD from 4 mice per group. (B) Microscopic images (original magnification, ×20) of liver sections stained either with Prussian blue ([a-d] duplicates from 2 different mice of each genotype or H&E [e-f]). Images taken at a ×20 original magnification were captured at room temperature under Leica DM5500B upright microscope using either an α Retiga SRV Cooled CCD camera for Prussian blue images or with a Leica DFC425C camera for H&E images. Staining with Prussian blue reflects the iron deposits in Kupffer cells derived from phagocytosed erythrocytes. H&E staining shows hematopoietic foci (black arrows) and phagocytosed RBCs (arrowheads) in Plg+/+ and Plg−/− liver. Images are representative of 4 mice per group. (C) Quantification of Prussian blue stain in liver sections derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. (D) Quantification of RBCs in liver sections derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Bars are mean ± SD of average area of Prussian blue or RBCs per microscopic field. Three to 5 microscopic fields were quantified from 4 mice per group.

Plg deficiency diminishes IgG-mediated erythrocyte phagocytosis in vivo.Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-mouse RBC mAb 34-3C to induce experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia. (A) Hematocrits in mice 3 days after injection of PBS or anti-RBC mAb 34-3C. Bars are mean ± SD from 4 mice per group. (B) Microscopic images (original magnification, ×20) of liver sections stained either with Prussian blue ([a-d] duplicates from 2 different mice of each genotype or H&E [e-f]). Images taken at a ×20 original magnification were captured at room temperature under Leica DM5500B upright microscope using either an α Retiga SRV Cooled CCD camera for Prussian blue images or with a Leica DFC425C camera for H&E images. Staining with Prussian blue reflects the iron deposits in Kupffer cells derived from phagocytosed erythrocytes. H&E staining shows hematopoietic foci (black arrows) and phagocytosed RBCs (arrowheads) in Plg+/+ and Plg−/− liver. Images are representative of 4 mice per group. (C) Quantification of Prussian blue stain in liver sections derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. (D) Quantification of RBCs in liver sections derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Bars are mean ± SD of average area of Prussian blue or RBCs per microscopic field. Three to 5 microscopic fields were quantified from 4 mice per group.

Plg modulates gene expression in response to phagocytosis stimuli

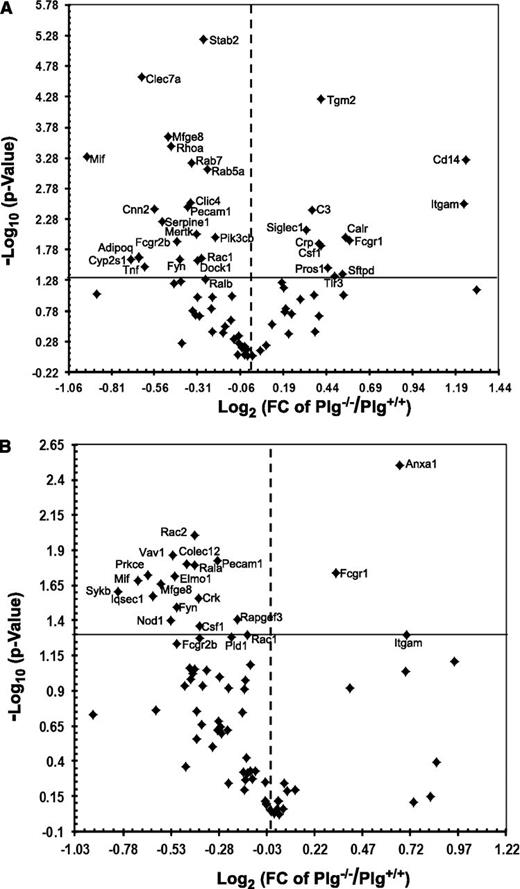

To evaluate whether phagocytic stimuli trigger Plg-dependent gene expression, liver mRNA was isolated from anti-RBC autoantibody treated mice and spleen mRNA from apoptotic thymocytes-treated mice. These samples were profiled using the mouse phagocytosis PCR array kits. Among the 85 genes analyzed, 30 genes in the liver (Figure 5A) and 13 in the spleen (Figure 5B) were significantly downregulated in Plg−/− mice compared with Plg+/+ mice (Table 1). Among the downregulated genes were several phagocytic receptors: Clec7a (liver), Colec12 (spleen), Fcgr2b, Mfge8 and Pecam1; recognition and engulfment molecules: Tnf (liver) and Mif, Crk (spleen), Csf1 (spleen) and Elmo1 (spleen); phagosome maturation genes: Cnn2 (liver), Rab5a (liver) and Rab7 (liver), Iqsec1 (spleen) and Pld1 (spleen); phagosome processing genes: Cyp2s1, Serpine and Stab2 in liver and Nod1 in spleen and signal transduction molecules, Adipoq, Click 4, Fyn, Mertk, Rhoa, Rac1, Ralb, Dock1, Pi3cb in liver and Rac2, Vav1, Prkce, Sykb, Fyn, Rac1, Rapgef3 in spleen. The gene names are elaborated in Table 1. Thus, Plg may regulate phagocytosis by modulating genes governing multiple steps in the phagocytic pathway.

Plg modulates phagocytosis-related genes in liver and spleen. Volcano plots of RT2PCR phagocytosis arrays comparing statistically significant gene expression changes in liver (A) and spleen (B) of Plg+/+ mice to Plg−/− mice. Log 2 values of the fold changes are plotted on the x-axis; the –log 10 transformed P values are plotted on the y-axis. The values are obtained from 3 replicates of raw Ct data. The solid line in the graphs marks the P value of .05, and the dotted line marks a onefold change. Thirty genes in the liver and 13 in the spleen were significantly downregulated in Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ mice (top left, P ≤ .05). Twelve genes in the liver and 3 genes in the spleen were significantly upregulated (top right, P ≤ .05).

Plg modulates phagocytosis-related genes in liver and spleen. Volcano plots of RT2PCR phagocytosis arrays comparing statistically significant gene expression changes in liver (A) and spleen (B) of Plg+/+ mice to Plg−/− mice. Log 2 values of the fold changes are plotted on the x-axis; the –log 10 transformed P values are plotted on the y-axis. The values are obtained from 3 replicates of raw Ct data. The solid line in the graphs marks the P value of .05, and the dotted line marks a onefold change. Thirty genes in the liver and 13 in the spleen were significantly downregulated in Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ mice (top left, P ≤ .05). Twelve genes in the liver and 3 genes in the spleen were significantly upregulated (top right, P ≤ .05).

qPCR array analysis of liver and spleen

| Gene name . | Gene symbols . | Liver . | Liver . | Spleen . | Spleen . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change* . | P . | Fold change* . | P . | ||

| Adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing | Adipoq | 0.64 | .022826† | 1.02 | .870631 |

| Advanced glycosylation end-product-specific receptor | Ager | 0.64 | .021826† | 0.82 | .241839 |

| Annexin A1 | Anxa1 | 0.89 | .377359 | 1.59 | .003136† |

| AXL receptor tyrosine kinase | Axl | 0.93 | .490164 | 0.94 | .469823 |

| Complement component 3 | C3 | 1.28 | .003722† | 0.11 | .259802 |

| Calreticulin | Calr | 1.46 | .010282† | 0.91 | .37959 |

| CD14 antigen | Cd14 | 2.38 | .00056† | 0.90 | .640137 |

| CD36 antigen | Cd36 | 0.79 | .164021 | 0.98 | .798815 |

| CD44 antigen | Cd44 | 0.95 | .572287 | 0.82 | .208215 |

| CD47 antigen (Rh-related antigen, integrin-associated signal transducer) | Cd47 | 0.86 | .10013 | 1.77 | .709099 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 3 | Ceacam3 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| C-type lectin domain family 7, member a | Clec7a | 0.65 | .000025† | 0.97 | .774483 |

| Chloride intracellular channel 4 (mitochondrial) | Clic4 | 0.79 | .002799† | 0.97 | .562036 |

| Calponin 2 | Cnn2 | 0.68 | .003551† | 0.80 | .314429 |

| Collectin subfamily member 12 | Colec12 | 0.98 | .735378 | 0.73 | .01582† |

| V-crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog (avian) | Crk | 0.90 | .298475 | 0.77 | .027703† |

| C-reactive protein, pentraxin-related | Crp | 1.31 | .013305† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Colony-stimulating factor 1 (macrophage) | Csf1 | 1.33 | .014056† | 0.77 | .043912† |

| Colony-stimulating factor 2 (granulocyte-macrophage) | Csf2 | 0.76 | .554382 | 1.67 | .777404 |

| C-src tyrosine kinase | Csk | 1.3 | .370645 | 0.65 | .172049 |

| Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily s, polypeptide 1 | Cyp2s1 | 0.61 | .024005† | 0.85 | .576908 |

| Dedicator of cytokinesis 1 | Dock1 | 0.81 | .024938† | 0.92 | .466954 |

| Dedicator of cytokinesis 2 | Dock2 | 0.95 | .861987 | 0.73 | .115206 |

| Engulfment and cell motility 1, ced-12 homolog (C elegans) | Elmo1 | 0.76 | .055912 | 0.70 | .019194† |

| Fas (TNF receptor superfamily member 6) | Fas | 1.29 | .091078 | 0.75 | .089305 |

| Fc receptor, IgE, high-affinity I, γ polypeptide | Fcer1g | 1.06 | .609571 | 0.90 | .477472 |

| Fc receptor, IgG, high-affinity I | Fcgr1 | 1.49 | .011813† | 1.62 | .091199 |

| Fc receptor, IgG, low-affinity IIb | Fcgr2b | 0.74 | .012309† | 0.77 | .052798 |

| Fc receptor, IgG, low-affinity III | Fcgr3 | 0.95 | .42037 | 1.26 | .018224† |

| Fyn proto-oncogene | Fyn | 0.752 | .023546† | 0.71 | .031913† |

| GULP, engulfment adaptor PTB domain containing 1 | Gulp1 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Interferon γ | Ifng | 0.64 | .021826† | 0.73 | .439154 |

| Interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 | Il1rl1 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.93 | .077434 |

| IQ motif and Sec7 domain 1 | Iqsec1 | 1.18 | .188148 | 0.65 | .026589† |

| Integrin α M | Itgam | 2.36 | .002989† | 1.63 | .050069 |

| Integrin α V | Itgav | 0.93 | .095144 | 0.76 | .177878 |

| Integrin β 2 | Itgb2 | 0.81 | .20262 | 0.91 | .106374 |

| Yamaguchi sarcoma viral (v-yes-1) oncogene homolog | Lyn | 0.98 | .710285 | 0.92 | .082347 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | Mapk14 | 0.98 | .675627 | 1 | .911288 |

| Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure | Marco | 1.22 | .109189 | 1.04 | .577212 |

| Mannose-binding lectin (protein C) 2 | Mbl2 | 0.96 | .67019 | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Mucolipin 3 | Mcoln3 | 0.64 | .021826† | 0.83 | .099829 |

| C-mer proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase | Mertk | 0.80 | .009257† | 0.98 | .773705 |

| Milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 protein | Mfge8 | 0.71 | .000236† | 0.67 | .021755† |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | Mif | 0.56 | .000498† | 0.61 | .02087† |

| Moesin | Msn | 0.92 | .239447 | 0.75 | .094797 |

| Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 | Myd88 | 0.81 | .097953 | 0.74 | .087204 |

| Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 1 | Nod1 | 0.97 | .854512 | 0.69 | .040064† |

| Platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 | Pecam1 | 0.78 | .003327† | 0.82 | .014935† |

| Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, catalytic, β polypeptide | Pik3cb | 0.87 | .010491† | 1.03 | .948485 |

| Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase, type 1 α | Pip5k1a | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.32 | .120657 |

| Phospholipase A2, group IVA (cytosolic, calcium-dependent) | Pla2g4a | 1.45 | .09121 | 1.81 | .40386 |

| Phospholipase A2, group V | Pla2g5 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.01 | .936996 |

| Phospholipase D1 | Pld1 | 1.15 | .154763 | 0.86 | .052754 |

| Phospholipase D2 | Pld2 | 1.17 | .400898 | 0.83 | .226317 |

| Protein kinase C, ε | Prkce | 0.99 | .903633 | 0.64 | .01899† |

| Protein S (α) | Pros1 | 1.37 | .033477† | 0.98 | .8042 |

| Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Pten | 1.09 | .277962 | 0.78 | .115533 |

| RAB5A, member RAS oncogene family | Rab5a | 0.84 | .000814† | 0.77 | .21849 |

| RAB7, member RAS oncogene family | Rab7 | 0.79 | .000643† | 0.82 | .237774 |

| RAS-related C3 botulinum substrate 1 | Rac1 | 0.82 | .022787† | 0.91 | .050714 |

| RAS-related C3 botulinum substrate 2 | Rac2 | 1.13 | .056517 | 0.76 | .009861† |

| V-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog A (ras related) | Rala | 0.80 | .190775 | 0.75 | .016177† |

| V-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog B (ras related) | Ralb | 0.83 | .050971 | 0.90 | .123584 |

| Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 3 | Rapgef3 | 0.54 | .089669 | 0.88 | .038894† |

| Ras homolog gene family, member A | Rhoa | 0.73 | .000332† | 0.89 | .180041 |

| Scavenger receptor class B, member 1 | Scarb1 | 1.14 | .070894 | 1.05 | .655597 |

| Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 | Serpine1 | 0.70 | .005876† | 0.76 | .277016 |

| Surfactant-associated protein D | Sftpd | 1.45 | .04158† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 1, sialoadhesin | Siglec1 | 1.25 | .007915† | 0.93 | .537381 |

| Signal-regulatory protein β 1A | Sirpb1a | 2.48 | .075493 | 1.04 | .87213 |

| Stabilin 2 | Stab2 | 0.83 | .000006† | 0.85 | .239987 |

| Syntaxin 18 | Stx18 | 1.15 | .175211 | 0.85 | .119873 |

| Spleen tyrosine kinase | Sykb | 1.32 | .204417 | 0.57 | .024911† |

| Transglutaminase 2, C polypeptide | Tgm2 | 1.33 | .000057† | 0.99 | .894431 |

| Toll-like receptor adaptor molecule 1 | Ticam1 | 0.73 | .059132 | 0.83 | .251845 |

| Toll-like receptor 3 | Tlr3 | 1.40 | .044291† | 0.91 | .544885 |

| Toll-like receptor 9 | Tlr9 | 1.04 | .740029 | 0.79 | .089971 |

| Tumor necrosis factor | Tnf | 0.65 | .031306† | 0.71 | .057986 |

| Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11 | Tnfsf11 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.08 | .639823 |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 | Vamp7 | 0.98 | .640446 | 0.92 | .490228 |

| Vav 1 oncogene | Vav1 | 1.01 | .908941 | 0.7 | .013642† |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome homolog (human) | Was | 0.85 | .150303 | 0.74 | .104693 |

| Wingless-related MMTV integration site 5A | Wnt5a | 0.86 | .367722 | 0.52 | .186013 |

| Gene name . | Gene symbols . | Liver . | Liver . | Spleen . | Spleen . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change* . | P . | Fold change* . | P . | ||

| Adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing | Adipoq | 0.64 | .022826† | 1.02 | .870631 |

| Advanced glycosylation end-product-specific receptor | Ager | 0.64 | .021826† | 0.82 | .241839 |

| Annexin A1 | Anxa1 | 0.89 | .377359 | 1.59 | .003136† |

| AXL receptor tyrosine kinase | Axl | 0.93 | .490164 | 0.94 | .469823 |

| Complement component 3 | C3 | 1.28 | .003722† | 0.11 | .259802 |

| Calreticulin | Calr | 1.46 | .010282† | 0.91 | .37959 |

| CD14 antigen | Cd14 | 2.38 | .00056† | 0.90 | .640137 |

| CD36 antigen | Cd36 | 0.79 | .164021 | 0.98 | .798815 |

| CD44 antigen | Cd44 | 0.95 | .572287 | 0.82 | .208215 |

| CD47 antigen (Rh-related antigen, integrin-associated signal transducer) | Cd47 | 0.86 | .10013 | 1.77 | .709099 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 3 | Ceacam3 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| C-type lectin domain family 7, member a | Clec7a | 0.65 | .000025† | 0.97 | .774483 |

| Chloride intracellular channel 4 (mitochondrial) | Clic4 | 0.79 | .002799† | 0.97 | .562036 |

| Calponin 2 | Cnn2 | 0.68 | .003551† | 0.80 | .314429 |

| Collectin subfamily member 12 | Colec12 | 0.98 | .735378 | 0.73 | .01582† |

| V-crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog (avian) | Crk | 0.90 | .298475 | 0.77 | .027703† |

| C-reactive protein, pentraxin-related | Crp | 1.31 | .013305† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Colony-stimulating factor 1 (macrophage) | Csf1 | 1.33 | .014056† | 0.77 | .043912† |

| Colony-stimulating factor 2 (granulocyte-macrophage) | Csf2 | 0.76 | .554382 | 1.67 | .777404 |

| C-src tyrosine kinase | Csk | 1.3 | .370645 | 0.65 | .172049 |

| Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily s, polypeptide 1 | Cyp2s1 | 0.61 | .024005† | 0.85 | .576908 |

| Dedicator of cytokinesis 1 | Dock1 | 0.81 | .024938† | 0.92 | .466954 |

| Dedicator of cytokinesis 2 | Dock2 | 0.95 | .861987 | 0.73 | .115206 |

| Engulfment and cell motility 1, ced-12 homolog (C elegans) | Elmo1 | 0.76 | .055912 | 0.70 | .019194† |

| Fas (TNF receptor superfamily member 6) | Fas | 1.29 | .091078 | 0.75 | .089305 |

| Fc receptor, IgE, high-affinity I, γ polypeptide | Fcer1g | 1.06 | .609571 | 0.90 | .477472 |

| Fc receptor, IgG, high-affinity I | Fcgr1 | 1.49 | .011813† | 1.62 | .091199 |

| Fc receptor, IgG, low-affinity IIb | Fcgr2b | 0.74 | .012309† | 0.77 | .052798 |

| Fc receptor, IgG, low-affinity III | Fcgr3 | 0.95 | .42037 | 1.26 | .018224† |

| Fyn proto-oncogene | Fyn | 0.752 | .023546† | 0.71 | .031913† |

| GULP, engulfment adaptor PTB domain containing 1 | Gulp1 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Interferon γ | Ifng | 0.64 | .021826† | 0.73 | .439154 |

| Interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 | Il1rl1 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.93 | .077434 |

| IQ motif and Sec7 domain 1 | Iqsec1 | 1.18 | .188148 | 0.65 | .026589† |

| Integrin α M | Itgam | 2.36 | .002989† | 1.63 | .050069 |

| Integrin α V | Itgav | 0.93 | .095144 | 0.76 | .177878 |

| Integrin β 2 | Itgb2 | 0.81 | .20262 | 0.91 | .106374 |

| Yamaguchi sarcoma viral (v-yes-1) oncogene homolog | Lyn | 0.98 | .710285 | 0.92 | .082347 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | Mapk14 | 0.98 | .675627 | 1 | .911288 |

| Macrophage receptor with collagenous structure | Marco | 1.22 | .109189 | 1.04 | .577212 |

| Mannose-binding lectin (protein C) 2 | Mbl2 | 0.96 | .67019 | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Mucolipin 3 | Mcoln3 | 0.64 | .021826† | 0.83 | .099829 |

| C-mer proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase | Mertk | 0.80 | .009257† | 0.98 | .773705 |

| Milk fat globule-EGF factor 8 protein | Mfge8 | 0.71 | .000236† | 0.67 | .021755† |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | Mif | 0.56 | .000498† | 0.61 | .02087† |

| Moesin | Msn | 0.92 | .239447 | 0.75 | .094797 |

| Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 | Myd88 | 0.81 | .097953 | 0.74 | .087204 |

| Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 1 | Nod1 | 0.97 | .854512 | 0.69 | .040064† |

| Platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 | Pecam1 | 0.78 | .003327† | 0.82 | .014935† |

| Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, catalytic, β polypeptide | Pik3cb | 0.87 | .010491† | 1.03 | .948485 |

| Phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase, type 1 α | Pip5k1a | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.32 | .120657 |

| Phospholipase A2, group IVA (cytosolic, calcium-dependent) | Pla2g4a | 1.45 | .09121 | 1.81 | .40386 |

| Phospholipase A2, group V | Pla2g5 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.01 | .936996 |

| Phospholipase D1 | Pld1 | 1.15 | .154763 | 0.86 | .052754 |

| Phospholipase D2 | Pld2 | 1.17 | .400898 | 0.83 | .226317 |

| Protein kinase C, ε | Prkce | 0.99 | .903633 | 0.64 | .01899† |

| Protein S (α) | Pros1 | 1.37 | .033477† | 0.98 | .8042 |

| Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Pten | 1.09 | .277962 | 0.78 | .115533 |

| RAB5A, member RAS oncogene family | Rab5a | 0.84 | .000814† | 0.77 | .21849 |

| RAB7, member RAS oncogene family | Rab7 | 0.79 | .000643† | 0.82 | .237774 |

| RAS-related C3 botulinum substrate 1 | Rac1 | 0.82 | .022787† | 0.91 | .050714 |

| RAS-related C3 botulinum substrate 2 | Rac2 | 1.13 | .056517 | 0.76 | .009861† |

| V-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog A (ras related) | Rala | 0.80 | .190775 | 0.75 | .016177† |

| V-ral simian leukemia viral oncogene homolog B (ras related) | Ralb | 0.83 | .050971 | 0.90 | .123584 |

| Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 3 | Rapgef3 | 0.54 | .089669 | 0.88 | .038894† |

| Ras homolog gene family, member A | Rhoa | 0.73 | .000332† | 0.89 | .180041 |

| Scavenger receptor class B, member 1 | Scarb1 | 1.14 | .070894 | 1.05 | .655597 |

| Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 | Serpine1 | 0.70 | .005876† | 0.76 | .277016 |

| Surfactant-associated protein D | Sftpd | 1.45 | .04158† | 1.02 | .761682 |

| Sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectin 1, sialoadhesin | Siglec1 | 1.25 | .007915† | 0.93 | .537381 |

| Signal-regulatory protein β 1A | Sirpb1a | 2.48 | .075493 | 1.04 | .87213 |

| Stabilin 2 | Stab2 | 0.83 | .000006† | 0.85 | .239987 |

| Syntaxin 18 | Stx18 | 1.15 | .175211 | 0.85 | .119873 |

| Spleen tyrosine kinase | Sykb | 1.32 | .204417 | 0.57 | .024911† |

| Transglutaminase 2, C polypeptide | Tgm2 | 1.33 | .000057† | 0.99 | .894431 |

| Toll-like receptor adaptor molecule 1 | Ticam1 | 0.73 | .059132 | 0.83 | .251845 |

| Toll-like receptor 3 | Tlr3 | 1.40 | .044291† | 0.91 | .544885 |

| Toll-like receptor 9 | Tlr9 | 1.04 | .740029 | 0.79 | .089971 |

| Tumor necrosis factor | Tnf | 0.65 | .031306† | 0.71 | .057986 |

| Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11 | Tnfsf11 | 0.64 | .021826† | 1.08 | .639823 |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein 7 | Vamp7 | 0.98 | .640446 | 0.92 | .490228 |

| Vav 1 oncogene | Vav1 | 1.01 | .908941 | 0.7 | .013642† |

| Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome homolog (human) | Was | 0.85 | .150303 | 0.74 | .104693 |

| Wingless-related MMTV integration site 5A | Wnt5a | 0.86 | .367722 | 0.52 | .186013 |

Fold change (2−ΔΔCT) is the normalized gene expression (2−ΔCT) in the Plg−/− samples divided by the normalized gene expression (2−ΔCT) in the Plg+/+ samples. Therefore, fold-change values <1 indicate a downregulation.

P value <.05.

To validate the observed changes in gene expression in tissues were macrophage related, J774A.1 cells, treated with or without Plg (24 hours), was subjected to mRNA analyses. Four representative genes (Fcgr2b, Mif, Sykb and Tnf), were selected for quantitation in the J774A.1 cells based on the changes observed in the tissue profiles. Among these, Fcgr2b, Syk, and Tnf were expressed at significantly higher levels in Plg treated J774A.1 cells compared with the untreated cells (supplemental Table 1). When Plg treated cells were subjected to beads phagocytosis, an increase by up to 79% in Syk (P = .006) and 26% in Tnf (P = .001) was observed compared with untreated cells.

Discussion

Evidence continues to mount to implicate Plg in cell biology in general and macrophage response in particular (reviewed in Miles et al24 ). Recently, we showed that Plg enhances lipid uptake by macrophages via modulating scavenger receptor expression.9 This observation led us to consider whether Plg might also influence the phagocytic function of macrophages. The present study provides both in vivo and in vitro evidence for a role of Plg, Plg receptors and plasmin activity in clearance of apoptotic and IgG-opsonized bodies. Additionally, we show that Plg supports changes in gene expression to favor uptake of these common targets of phagocytosis.

Inactivation of the Plg gene in mice delayed clearance of apoptotic bodies by splenic macrophages. Consequently, the dying cells accumulated in the spleen of the Plg-deficient compared with wild-type mice. Furthermore, uptake of the same apoptotic bodies was impaired by murine macrophage-like cell line in the absence of Plg. Plg was even able to enhance phagocytic activity of macrophages that had been stimulated with an inflammatory stimulus, LPS mimicking circumstances that the cells are likely to encounter in vivo. Efficient clearance of dead or dying cells by macrophages is critical in tissue remodeling and resolution of inflammation.3,25,26 Poor clearance of such bodies can induce an inflammatory burden and lead to autoimmune responses due to exposure of cytosolic components.3,26 Although Plg facilitates the guidance of inflammatory cells to sites of injury,27 delayed clearance of cellular debris in Plg−/− mice might provoke inflammation and autoimmune responses in the long-term. In fact, deficiency of Plg or presence of antibodies to Plg receptors has been correlated with several autoimmune and inflammatory diseases including celiac disease,28 rheumatoid arthritis,29 lupus erythematosus,30 systemic sclerosis31 and anti-phospholipid syndrome.32 These diseases do not occur spontaneously in Plg−/− mice and may require immune challenge to provoke a pathological response. Poor phagocytic activity of macrophages leads to the formation of a necrotic core in the later stages of atherosclerosis.33 Such inefficient clearance of aging macrophages and other cellular debris may explain the exacerbated growth of atheroma in Plg−/− mice at the later stages of atherosclerosis34 counterbalancing the aceleration of earlier stages of atherosclerosis observed in Plg−/− mice,35 arising from suppressed macrophage recruitment and/or reduced foam cell formation.

Macrophage phagocytosis is also important in the pathogenesis of antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases.1,22 Reduced hematocrits in blood and increased incorporation of iron into liver cells of Plg+/+ compared with Plg−/− mice provides evidence that Plg facilitates clearance of autoantibody-coated erythrocytes. The number of Kupffer cells in the livers of Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice was similar based on F4/80 staining, consistent with a previous report that proliferation of liver cells is not affected by Plg deficiency.36 These data suggest that Plg−/− mice might protect against development of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Reticuloendothelial macrophages are responsible for recycling hemoglobin iron acquired by phagocytosis of senescent erythrocytes.37 The absence of Plg might impair iron homeostasis in mice; however, this function may only become evident in the face of challenge as we did not observe differences in basal hematocrits and Prussian blue staining in the 2 genotypes. The capacity of Plg to regulate phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized RBC also suggests that Plg may play a role in removal of pathogenic microbes opsonized with antibodies with or without complement.

Our study provides further evidence that Plg modulates gene expression in macrophages. De novo protein synthesis was required for Plg-dependent phagocytosis. Furthermore, gene profiling showed downregulation of many phagocytic-related genes in organs derived from Plg−/− mice. These genes are known to be involved in recognition, binding and engulfment of phagocytic materials, maturation and processing of phagosomes and in signal transduction. A few of the regulated genes deserve special mention. Mif, a proinflammatory cytokine, activates macrophages and sustains their survival leading to increased uptake and clearance of bacteria and cellular debris.33,34 Because of its broad role in amplifying inflammatory responses and resolving inflammation, this cytokine has been implicated in both innate and adaptive immunity. In liver, Mif was the most diminished mRNA (44% inhibition, P = 5E−04) in Plg−/− mice treated with anti-RBC and it was also downregulated in spleens derived from Plg−/− mice treated with IgG-opsonized erythrocytes. Mif was also found upregulated when J774A.11 cells were treated with Plg. Therefore, Mif might play a critical role in Plg-mediated phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized erythrocytes as well as apoptotic thymocytes. Stabilin-2 showed the most significant downregulation (P = 6E−06) of any mRNA in Plg−/− liver. Stabilin-2 regulates phagosome maturation and was previously shown to facilitate removal of aged and damaged RBC by liver Kupffer cells.35 The absence of Plg also caused upregulation of certain genes (eg, Fcgr1 and Itgam), which are important promoters of phagocytosis.1,38

Recognition of phagocytic materials generates intracellular signals that enhance phagocytic function of macrophages. Decreased ingestion of apoptotic bodies could result from inefficient post-recognition signaling. Sykb was the most diminished (43% inhibition, P = .02) mRNA in spleens derived Plg−/− mice exposed to apoptotic thymocytes. Additionally, J77A.1 cells treated with Plg showed increased Sykb expression. Activation of Sykb protein promotes macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic thymocytes.36 Actin reorganization controls the formation of engulfment cup during phagocytosis. This process is controlled by many Rho GTPases including RhoA, Rac1 and Rac2.37 Rac2 was the most significantly diminished (24%, P = .009) mRNA in Plg−/− spleens exposed to apoptotic thymocytes. Therefore, Plg might also promote clearance of apoptotic thymocytes by enhancing expression of specific intracellular signaling proteins. Hence, deficiency of Plg causes intrinsic defects in phagocytes contributing to the uptake of various targets. Our gene array analysis also provides examples of genes that Plg affects differently in response to different phagocytic stimuli (IgG opsonized vs apoptotic bodies) and in an organ specific manner (liver vs spleen).

Plasmin proteolytic activity was essential in altering phagocytic activity of macrophages. The targets of plasmin remain to be identified. One possibility is plasmin-mediated release of growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor, tumor growth factor β and hepatocyte growth factor, which are known to modulate transcriptome machinery and phagocytic activity of macrophages.39,,-42 Plasmin might also be involved, either directly or indirectly, in activating protease activated receptors, which could influence phagocytosis by stimulating downstream signaling from these G-protein coupled receptors,43,44 which in turn might induce expression of phagocytic related genes.

In sum, Plg is a key regulator of macrophage phagocytosis. Plg enhances phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized bodies and clearance of apoptotic thymocytes by modulating expression of multiple genes. With this identification of Plg as a regulator of innate immune system, this study provides an impetus to consider Plg and its activation as targets for intervention in immune deficient states.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Peterson of the Lerner Research Institute Imaging Core for help with microscopy.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant (HL017964; E.F.P.) and American Heart Association Scientist Development grant (11SDG7390041; R.D.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.D. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.G. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; M. S. performed research; and E.F.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Riku Das, Department of Molecular Cardiology, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave/NB50, Cleveland, OH 44195; e-mail: dasr@ccf.org.

![Figure 4. Plg deficiency diminishes IgG-mediated erythrocyte phagocytosis in vivo. Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-mouse RBC mAb 34-3C to induce experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia. (A) Hematocrits in mice 3 days after injection of PBS or anti-RBC mAb 34-3C. Bars are mean ± SD from 4 mice per group. (B) Microscopic images (original magnification, ×20) of liver sections stained either with Prussian blue ([a-d] duplicates from 2 different mice of each genotype or H&E [e-f]). Images taken at a ×20 original magnification were captured at room temperature under Leica DM5500B upright microscope using either an α Retiga SRV Cooled CCD camera for Prussian blue images or with a Leica DFC425C camera for H&E images. Staining with Prussian blue reflects the iron deposits in Kupffer cells derived from phagocytosed erythrocytes. H&E staining shows hematopoietic foci (black arrows) and phagocytosed RBCs (arrowheads) in Plg+/+ and Plg−/− liver. Images are representative of 4 mice per group. (C) Quantification of Prussian blue stain in liver sections derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. (D) Quantification of RBCs in liver sections derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. Bars are mean ± SD of average area of Prussian blue or RBCs per microscopic field. Three to 5 microscopic fields were quantified from 4 mice per group.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/5/10.1182_blood-2014-01-549659/2/m_679f4.jpeg?Expires=1767706268&Signature=omTdk3DleHfoQfqE5NGX8S6jHGSmL-Ilp2ClZwMOIlifucQvvFMxgXCo5IP-kAkxPrl12m3wU9AWpuqF6UlCYaF7Q4TLTpkWEXG569Ymgl1FYGPrr0fOrwGae~ckrFMLIyF9pFrO71KmgnYodowAvyKejvKa2dOuTK-l7k72hSY0Pd0ChX8jHRwd5F-a4E65XGOXGSOeg-Q5-SOtIhtZe4O7-a5DJGkNcCXUlTbG7RK2p-tKPfVL-XGtQOX9bH6sdJVWwbnqrgul0TPAWXmfbQyhIqeyQUInGzJR~3txXwSXw5-zzT1PQfw6PU7WOiejfwdy-gN-R8D7oY4dD3pKUQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)