Introduction: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have revolutionized Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) treatment by lowering the disease burden by providing more precise monitoring of response. However, review of new clinical trial data and updating management principles is essential to ensure continued optimal outcome for patients while minimizing treatment toxicity. The European Leukemia Net (ELN) has developed guidelines for CML management in 2006, 2009 with updates in 2013. They define optimal use of TKIs in first and second-line setting, best approach for monitoring and evaluating treatment responses, and evidence based management interventions for suboptimal responses. One study has shown achievement of Major Molecular Response (MMRs) at 12 months, compared with the lack of MMRs at this time point, had been associated with superior event-free survival and lack of progression to the accelerated or acute phase (Hughes TP, et al.). German CML Study IV supports these results as well. Even with this evidence, data suggest that 20% to 30% patients with CML are not being treated according to current CML guidelines (Quintas-Cardama A, et al). This retrospective chart review will compare management of CML patients in Saskatchewan, Canada with the suggested ELN guidelines, specifically looking for changes in management for suboptimal responses or patient toxicity, and will determine if Saskatchewan patient management requires further optimization.

Methods: The charts of CML patients from Saskatchewan Cancer Centre were retrospectively reviewed from January 2009 to December 2014. For each patient the following information was extracted: date of diagnosis, initial treatment and start date, response to treatment and any change in treatment based on test results as suggested by the ELN guidelines. Timing of treatment response evaluation as per ELN guidelines (1 month after treatment initiation followed by molecular testing at 3 month intervals), and interventions for suboptimal responses were recorded.

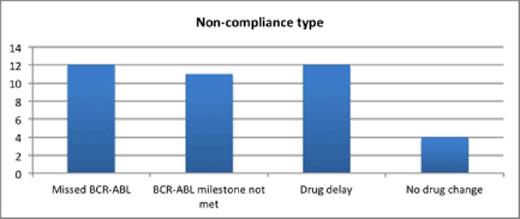

Results: 58 patients were diagnosed with CML in the study period. 23 (41%) patients were no longer on frontline TKI therapy and representing either failure of Imatinib (69.57%) or intolerance to Imatinib (30.43%). 24 (41.38%) patients were managed in accordance with ELN guidelines. 27(46.55%) patients were not managed according to ELN guidelines (Figure-1). Non-compliance varied from minor deviations with delays in monitoring response to therapy in 12 (20.69%) to major omissions such as not changing treatment based on suboptimal responses in 12 (20.69%) patients. In 11 (19%) patients, important milestone responses required for optimal patient outcome were not met and no change in therapy was evident. Most importantly, treatment failure as defined in the ELN guidelines, without a change in management occurred in 4 (7%) patients.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that management of CML at Saskatchewan Cancer Centre, according to ELN guidelines, occurs in less than 50% of patients. Most surprisingly, 7% of patients were defined as having failed treatment and in need of treatment change to prevent progression of their disease. This review suggests that management of CML patients in Saskatchewan requires further evaluation and potential interventions put in place to ensure optimal CML patient outcomes. The ELN guidelines are recognized worldwide to be the most up to date and evidence based guidelines for optimal CML patient management. Therefore, following CML treatment outcome should be a standard Hematology matrix, thereby creating treatment centres of excellence.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This icon denotes a clinically relevant abstract

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal