In this issue of Blood, Palladini et al report on the outcome of a large series of 230 patients with systemic immunoglobulin (Ig) amyloid light chain (AL) amyloidosis treated frontline with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) at 2 referral centers.1

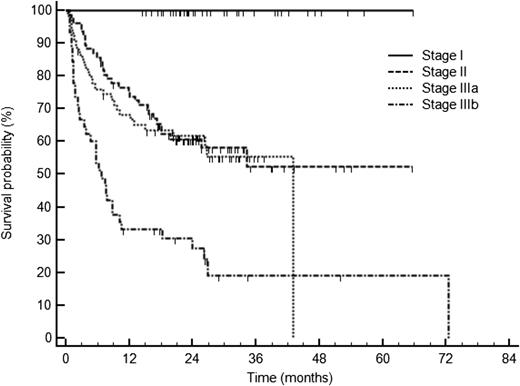

Survival of 230 patients with AL amyloidosis treated with CyBorD according to cardiac stage based on cardiac biomarkers: NT-proBNP (cutoff 322 ng/L) and troponin cTnT (cutoff 0.035 ng/mL), or cTnI (cutoff 0.1 ng/mL). Stage I, normal biomarkers; stage II, one marker above the cutoff; stage IIIa: both markers above the cutoff but NT-proBNP ≤8500 ng/L; and stage IIIb: NT-proBNP >8500 ng/L. See Figure 1B in the article by Palladini et al that begins on page 612.

Survival of 230 patients with AL amyloidosis treated with CyBorD according to cardiac stage based on cardiac biomarkers: NT-proBNP (cutoff 322 ng/L) and troponin cTnT (cutoff 0.035 ng/mL), or cTnI (cutoff 0.1 ng/mL). Stage I, normal biomarkers; stage II, one marker above the cutoff; stage IIIa: both markers above the cutoff but NT-proBNP ≤8500 ng/L; and stage IIIb: NT-proBNP >8500 ng/L. See Figure 1B in the article by Palladini et al that begins on page 612.

Systemic Ig AL amyloidosis is a plasma cell disorder characterized by the production of monoclonal light chains, usually of λ type, that misfold and result in amyloid aggregates. Organ damage in this disease is mediated both by organ deposition of amyloid aggregates and by direct cytotoxicity of circulating amyloidogenic light chains. Prognosis depends mainly on the presence and degree of cardiac involvement, measured by cardiac biomarkers, as well as on the disease burden, measured by the free light-chain amount. Accordingly, the choice of treatment will have to take into account both factors, ideally in a risk-adapted approach. Among the available treatment options, high-dose melphalan followed by stem cell transplant has demonstrated its ability to obtain high rates of hematologic and organ responses and, most importantly, long-term responses in this setting.2 However, a high transplant-related morbidity and mortality makes this treatment option not suitable for a significant proportion of patients. For nontransplant candidates, oral melphalan and dexamethasone has been considered the standard of care, but has shown to be less effective in patients with severe cardiac involvement mostly due to a high early death rate.3 Thus, any survival improvement in this disease requires an early detection of cardiac involvement and also rapid, deep, and durable reduction of the AL burden in order to avoid further progression of cardiac damage, and hopefully allow the recovery of organ function. In this sense, bortezomib showed its ability to obtain rapid and good-quality responses in previously treated patients,4 raising the possibility of further improving outcomes by upfront use of this drug and also by adding an alkylating agent and dexamethasone.

In 2012, 2 small retrospective studies reported high rates of hematologic response and excellent early outcomes using the combination CyBorD upfront or at relapse.5,6 In the first study, Mikhael et al reported 94% hematologic responses, including a complete response (CR) rate of 71% with a median duration of 22 months.5 In the second study, Venner et al reported 81% hematologic responses, including a CR rate of 42%, and interestingly, an estimated 2-year overall survival of 94% in the group of patients with Mayo stage III, suggesting that this treatment might overcome the poor prognosis associated to advanced-stage disease.6 Based on these exciting results, CyBorD was adopted as the new standard of care at many institutions. However, the retrospective design of these studies, the small number of patients included, possible selection bias, and short follow-up might explain why other groups have not been able to replicate the reported response rates. For example, a French study conducted in patients with Mayo Clinic stage III treated with CyBorD reported a 1-year mortality rate of 40% while on therapy.7 Moreover, 2 case-controlled series could not demonstrate a survival improvement by adding bortezomib to an alkylating agent plus dexamethasone, due to the high rate of early deaths in AL amyloidosis.8,9

Herein, Palladini et al report their experience in 230 patients with AL amyloidosis treated with upfront CyBorD at the National Amyloidosis Centre in the United Kingdom and at the Amyloidosis Research and Treatment Center in Pavia, Italy, between 2006 and 2013. In this large series, the overall hematologic response rate was 60%, including CR in 23% of patients. After a median follow-up of 25 months for living patients, cardiac and renal responses were obtained only in 17% and 25% of them, respectively. Regarding patients with advanced cardiac disease, those with NT-proBNP over 8500 ng/L (stage IIIb) had lower hematologic response rates (42%, CR 14%) and poorer survival (median of 7 months) due to the inability of CyBorD to reduce the early mortality in this high-risk population (see figure).

In conclusion, it seems that noncardiac patients with AL amyloidosis have an excellent outcome with high chances of benefit irrespective of the treatment approach. Also, patients with low-risk cardiac disease (stage II and IIIa) may benefit provided that they achieve at least a partial response, whereas high-risk cardiac patients (stage IIIb) still have a poor prognosis. Conclusions should be made with caution from retrospective studies. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon that promising results from small phase 2 trials or trials with short follow-up are not reproduced in larger series with adequate follow-up and particularly in real clinical practice. And finally, despite the contributions to our understanding of the treatment of AL amyloidosis made by Palladini et al, there are a number of unanswered questions regarding this treatment approach: Could CyBorD increase the number of younger patients eligible for autologous transplant? Would responses to CyBorD have an equivalent duration to those obtained with high-dose melphalan and, consequently, should these patients be or not be consolidated with high-dose melphalan? Should patients in CR after CyBorD proceed to autologous transplant? Future trials with enough follow-ups are needed to answer these questions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.T.C. received honoraria for educational lectures from Janssen and Celgene. J.B. received honoraria for educational lectures, advisory boards, and grant research from Janssen, Celgene, and Onyx.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal