Key Points

OSCAR has 2 immunoglobulin-like domains with an obtuse interdomain angle, differing from other members of the leukocyte receptor cluster.

Each domain of OSCAR binds a collagen triple-helical peptide; the primary site is on the C-terminal domain in contrast to GPVI and LAIR-1.

Abstract

The osteoclast-associated receptor (OSCAR) is a collagen-binding immune receptor with important roles in dendritic cell maturation and activation of inflammatory monocytes as well as in osteoclastogenesis. The crystal structure of the OSCAR ectodomain is presented, both free and in complex with a consensus triple-helical peptide (THP). The structures revealed a collagen-binding site in each immunoglobulin-like domain (D1 and D2). The THP binds near a predicted collagen-binding groove in D1, but a more extensive interaction with D2 is facilitated by the unusually wide D1-D2 interdomain angle in OSCAR. Direct binding assays, combined with site-directed mutagenesis, confirm that the primary collagen-binding site in OSCAR resides in D2, in marked contrast to the related collagen receptors, glycoprotein VI (GPVI) and leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1). Monomeric OSCAR D1D2 binds to the consensus THP with a KD of 28 µM measured in solution, but shows a higher affinity (KD 1.5 μM) when binding to a solid-phase THP, most likely due to an avidity effect. These data suggest a 2-stage model for the interaction of OSCAR with a collagen fibril, with transient, low-affinity interactions initiated by the membrane-distal D1, followed by firm adhesion to the primary binding site in D2.

Introduction

Leukocyte function is regulated by an array of cell surface receptors that continually probe the local extracellular tissue environment. The osteoclast-associated receptor (OSCAR) is an activating immunoreceptor expressed by osteoclasts, monocytes, and dendritic cells (DCs).1,2 OSCAR is one of many genes located in the leukocyte receptor complex (LRC), reviewed elsewhere,3 that encodes activating and inhibitory immunoglobulin superfamily receptors (supplemental Table 1, see supplemental Data available on the Blood Web site). Glycoprotein VI (GPVI) is another LRC-encoded collagen receptor that mediates platelet activation at sites of endothelial damage, precipitating platelet-mediated hemostasis, and has a domain structure similar to that of OSCAR. OSCAR binding to collagen epitopes exposed on remodeling bone surfaces drives RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand)–induced osteoclastogenesis.4 In the immune system, tissue inflammation was proposed to elicit the exposure of collagens that would then engage OSCAR and stimulate DC maturation.5 Recently, OSCAR was shown to bind the collagenous domains of pulmonary surfactant protein D to induce tumor necrosis factor-α secretion by inflammatory monocytes.6 Furthermore, the expression of OSCAR is regulated by atherogenic stimuli in myeloid cells,7 and by oxidized low-density lipoprotein in vascular endothelial cells,8 suggesting a role in atherogenesis.

The distal (N-terminal) and proximal extracellular immunoglobulin-like domains of OSCAR are known as D1 and D2, respectively. OSCAR is associated with the Fc receptor (FcR) common γ-chain (FcRγ), the cytoplasmic tail of which contains the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif that, upon ligand binding, mediates a signaling cascade that leads to cellular activation.1,9,10 The LRC also encodes 2 related collagen-binding proteins, the inhibitory, single immunoglobulin-like domain-containing receptor leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1) and its soluble decoy counterpart, LAIR-2.11,12 The cytoplasmic tail of LAIR-1 encodes an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif (ITIM) that mediates negative regulation of immunologic stimuli. Thus, the inhibitory LAIR-1, like the activatory OSCAR, is expressed by monocytes and DCs and also binds both collagen and surfactant protein D to inhibit immune cell function. How, then, does OSCAR separately engage collagenous ligands to activate the biological functions of osteoclasts, monocytes, and DCs?

There is some overlap between the specificity of OSCAR and the other LRC-encoded collagen receptors for collagen sequence, which have been mapped using the Collagen Toolkits.13 For example, GPVI binds glycine-proline-hydroxyproline (GPO)-rich tracts of collagen III,14 and is fully activated by a model triple-helical peptide (THP) containing only this model collagen sequence.15,16 The specificity of LAIR-1 and LAIR-2 for collagen overlaps that of GPVI, also relying on GPO-rich tracts.12 In contrast, OSCAR has been shown to bind to several loci in collagens II and III (not including peptide III-30, a good ligand for both GPVI and LAIR-1). A consensus motif, GXOGPXGFX, can account for most of these.4 Collagen II contains a second, unique imino-acid poor motif, GAOGASGDR, which contrasts markedly with the OSCAR-binding consensus motif and with those Toolkit peptides that are recognized by GPVI and the LAIRs.

Our purpose here was threefold: to explore the structure of OSCAR, to compare OSCAR with other LRC collagen receptors, and to examine OSCAR-collagen binding by solving the crystal structure of an OSCAR-THP complex.

Methods

Methods for peptide synthesis, production of OSCAR D1D2 proteins, crystal structure determination, analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC), and both solid-phase and in-solution binding assays are described in supplemental Methods.

Results

Both Escherichia coli– and mammalian cell–expressed human OSCAR ectodomains specifically recognize the consensus collagen motif, GPOGPAGFO

OSCAR has been mapped onto 6 main sites in human collagens II and III using the Collagen Toolkits.4 Here, we selected the same 6 THPs (Figure 1A) and some unreactive peptides as controls. We produced both refolded, bacterially-expressed OSCAR D1D2 and EndoH-trimmed, mammalian cell–expressed D1D2 and tested their ability to bind these peptides in solid-phase binding experiments. The peptides recognized by both forms of recombinant OSCAR D1D2 conformed to the consensus sequence, GXOGPXGFX, as previously reported.4 Although their relative binding to the various peptides differed slightly, only 1 peptide, DB92, with guest sequence (GPAGPAGFOGAO) that lacks the critical hydroxyproline residue Hyp-3, bound the E coli–expressed OSCAR D1D2 poorly compared with the mammalian cell product. This shows the 2 preparations to be closely equivalent, justifying subsequent comparisons. A distinct “orphan” motif, GAOGASGDR, demonstrated equally high affinity as GXOGPXGFX to both the E coli– and HEK293EBNA-expressed OSCAR ectodomains (Figure 1C), giving an apparent KD for the E coli–expressed protein on the order of 1 µM, measured using the solid-phase Bind Explorer biosensor (SRU Biosystems) (Figure 1D).

Design of a consensus collagen triple-helical peptide. (A) Table of collagenous peptide sequences used in solid-phase binding experiments. Collagen Toolkit peptides are identified by their numbers from Toolkits II and III, whereas derivative peptides are identified by their laboratory reference numbers. The consensus motifs, GXOGPXGFX or GAOGASGDR, are shown in black or red font, and segments of sequence that surround them are shown in gray. Not shown are the N- and C-terminal flanking motifs, GPC[GPP]5- and -[GPP]5GPC-amide, which are present on each peptide. Gpp10 denotes the control, GPC[GPP]10GPC-amide. (B) Polarimetry data of peptide DB316, Acetyl-GPOGPOGPOGPAGFOGPOGPO-amide were collected from 10°C to 70°C (up to 50°C is shown) at a ramp rate of 1°C min−1 as described in the supplemental Methods. First derivative of the original optical rotation data were used to define the peptide Tm. (C) Solid-phase binding of recombinant OSCAR (ectodomain E coli– or HEK293EBNA-expressed, 0.1 µg per well) on the collagenous peptides listed in panel A. Each peptide/protein combination was tested in triplicate, as described in supplemental Methods, and the inert peptide, (GPP)10, and BSA were used as negative controls. Data shown are mean ± SEM. (D) Biosensor curves of increasing concentrations of E coli–expressed recombinant OSCAR ectodomain titrated onto SRU 96-well plate coated by DB80, NR338, II-26, as well as (GPP)10 as negative control. Each point was collected in triplicate, and each data set was fitted to a model of specific and nonspecific binding in GraphPad Prism. The nonspecific binding curves were then removed for clarity. (E) Analytical gel filtration of recombinant OSCAR ectodomain preincubated with DB316 in different molar ratios. Each curve was derived separately using a Superdex 75 10/300gl column, running at 0.2 mL per minute, as described in supplemental Methods, and superimposed into 1 figure. Bmax, maximum binding; deg, degrees; dOR/dT, rate of change of optical rotation with temperature; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; mAU, milli absorbance units; OD, optical density; PWV, peak wavelength; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Design of a consensus collagen triple-helical peptide. (A) Table of collagenous peptide sequences used in solid-phase binding experiments. Collagen Toolkit peptides are identified by their numbers from Toolkits II and III, whereas derivative peptides are identified by their laboratory reference numbers. The consensus motifs, GXOGPXGFX or GAOGASGDR, are shown in black or red font, and segments of sequence that surround them are shown in gray. Not shown are the N- and C-terminal flanking motifs, GPC[GPP]5- and -[GPP]5GPC-amide, which are present on each peptide. Gpp10 denotes the control, GPC[GPP]10GPC-amide. (B) Polarimetry data of peptide DB316, Acetyl-GPOGPOGPOGPAGFOGPOGPO-amide were collected from 10°C to 70°C (up to 50°C is shown) at a ramp rate of 1°C min−1 as described in the supplemental Methods. First derivative of the original optical rotation data were used to define the peptide Tm. (C) Solid-phase binding of recombinant OSCAR (ectodomain E coli– or HEK293EBNA-expressed, 0.1 µg per well) on the collagenous peptides listed in panel A. Each peptide/protein combination was tested in triplicate, as described in supplemental Methods, and the inert peptide, (GPP)10, and BSA were used as negative controls. Data shown are mean ± SEM. (D) Biosensor curves of increasing concentrations of E coli–expressed recombinant OSCAR ectodomain titrated onto SRU 96-well plate coated by DB80, NR338, II-26, as well as (GPP)10 as negative control. Each point was collected in triplicate, and each data set was fitted to a model of specific and nonspecific binding in GraphPad Prism. The nonspecific binding curves were then removed for clarity. (E) Analytical gel filtration of recombinant OSCAR ectodomain preincubated with DB316 in different molar ratios. Each curve was derived separately using a Superdex 75 10/300gl column, running at 0.2 mL per minute, as described in supplemental Methods, and superimposed into 1 figure. Bmax, maximum binding; deg, degrees; dOR/dT, rate of change of optical rotation with temperature; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; mAU, milli absorbance units; OD, optical density; PWV, peak wavelength; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Next, we synthesized a shorter THP, DB316, with sequence Ac-(GPO)2-GPOGPAGFO-(GPO)2. This peptide assembled as a stable homotrimer with melting temperature (Tm) of 28°C; the symmetrical polarimetric unfolding curve (Figure 1B) indicates good purity and accurate assembly.17 To confirm solution-phase association between OSCAR D1D2 and DB316, different molar ratios of protein to peptide were examined by analytical gel filtration. Although the free and peptide-saturated D1D2 (a twofold excess of DB316) elute at ∼12.8 mL and 11.3 mL, respectively, 2 peaks were resolved at the same elution volumes from a mixture containing a 2:1 molar excess of D1D2, consistent with 1:1 peptide-to-OSCAR stoichiometry (Figure 1E).

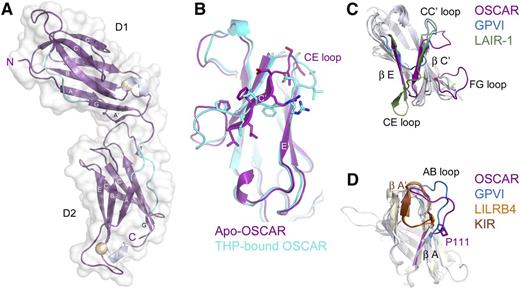

Crystal structure of the free collagen-binding ectodomain of OSCAR

Bacterially-expressed D1D2 was crystallized and the structure was solved by molecular replacement, using data complete to 2.0 Å (supplemental Table 2). OSCAR D1D2 consists of 2 immunoglobulin-like domains, connected by a short linker (Figure 2A). Each domain forms a C2-type immunoglobulin superfamily fold, with 2 β-sheets formed by strands ABED and C′CFG, each of which contains a short 310 helix in the EF loop connecting the E and F strands. There are stretches of polyproline type II helix upstream of the short G strand in both domains and upstream of the A strand in D2. OSCAR D1 is very similar to D1 of other LRC receptors, with root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values ranging from 1.221 Å (p58-CL42 killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor [KIR]) to 2.003 Å (free FcαRI). Interestingly, the closest structural homolog for OSCAR D1 reported by the Dali server is D2 of leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B4 (LILRB4). OSCAR D2 most closely resembles KIR D2 (r.m.s.d. 1.31 Å) and D1 of LILRB4 (r.m.s.d. 1.46 Å) (Figure 2C-D).

Crystal structure of OSCAR D1D2. (A) Crystal structure of free OSCAR D1D2, colored according to secondary structure (β-sheet, magenta; 310 helix, silver; polyproline-type II helix, cyan). Putative N-glycosylation sites are shown as spheres. Strands are labeled according to standard immunoglobulin-like domain topology. (B) Overlay of D1 of apo-OSCAR (magenta) and THP-bound OSCAR (cyan) to illustrate the shift of the C′ strand in the free receptor (residues 47-55, PLLFRDVSS; shown as sticks) to a D strand in the bound receptor. (C) Overlay of D1 from the collagen-binding LRC receptors OSCAR (magenta), GPVI (blue), and LAIR-1 (green). (D) Overlay of D2 from OSCAR (magenta), GPVI (blue), LILRB4 (orange), and p58-CL42 KIR (brown) to illustrate changes in the AB loop region and the cis vs trans conformation of residue Pro-111 (see supplemental Discussion).

Crystal structure of OSCAR D1D2. (A) Crystal structure of free OSCAR D1D2, colored according to secondary structure (β-sheet, magenta; 310 helix, silver; polyproline-type II helix, cyan). Putative N-glycosylation sites are shown as spheres. Strands are labeled according to standard immunoglobulin-like domain topology. (B) Overlay of D1 of apo-OSCAR (magenta) and THP-bound OSCAR (cyan) to illustrate the shift of the C′ strand in the free receptor (residues 47-55, PLLFRDVSS; shown as sticks) to a D strand in the bound receptor. (C) Overlay of D1 from the collagen-binding LRC receptors OSCAR (magenta), GPVI (blue), and LAIR-1 (green). (D) Overlay of D2 from OSCAR (magenta), GPVI (blue), LILRB4 (orange), and p58-CL42 KIR (brown) to illustrate changes in the AB loop region and the cis vs trans conformation of residue Pro-111 (see supplemental Discussion).

The ectodomain of OSCAR adopts a bent orientation, like other LRC members (LILRs, KIRs, NKp46, FcαRI, and GPVI) and the FcRs, FcγRIII and FcεRI. D1 and D2 in all other known LRC receptors adopt an orthogonal arrangement, with interdomain angles typically near 90°. These angles range from acute (66°) for p58-CL42 KIR to near-right angles for FcαRI (83°), GPVI (85°), NKp46 (85°), and LILRB1 (88°), to obtuse for LILRB4 (107°). In contrast, FcRs encoded on chromosome 1, such as FcγRIII or FcεRI, adopt acute interdomain angles (50° and 37°, respectively), but with D1 oriented on the opposite side relative to the D1 domains of LRC receptors. To aid comparison, we define the interdomain angles relative to the LRC receptors (see Figure 3A); thus, the interdomain angles for FcεRI and FcγRIII are 310° and 323°. Despite belonging to the LRC, OSCAR diverges significantly, with an interdomain angle of 241°. In fact, the position of D1 in OSCAR is closer to the configuration of FcγRIII and FcεRI than to other LRC receptors; D1 of OSCAR is rotated an additional 110° beyond D1 of LILRB4 (supplemental Table 3).

OSCAR D1-D2 domain interface. (A) Comparison of D1-D2 interdomain angles among OSCAR, representative LRC receptors, and FcγRIII. D2 domains from OSCAR (magenta), p58-CL42 KIR (blue), GPVI (red), LILRB4 (gold), and FcγRIII (green) were superimposed to illustrate the relative positions of D1. For purposes of comparison, the degrees of rotation are defined such that at 0°, D1 would be doubled back and occupying the same position as D2 (see circle with arrows illustrating the clockwise rotation describing the relative positions of D1 domains). (B) Comparative views of the D1-D2 linker in FcαRI (top), GPVI (middle), and OSCAR (bottom). Conserved residues at the D1-D2 junction are shown as transparent spheres and color-coded according to their positions in the sequence alignment. Most LRC receptors have a Thr-Gly-Φ-Φ motif that creates a sharp bend in the D1-D2 linker sequence and packs the hydrophobic (Φ) residues after Gly against other hydrophobic residues in D2. In OSCAR, the mostly conserved Gly residue and the subsequent hydrophobic residue are replaced by 2 large, negatively charged Glu residues, sterically preventing formation of the sharp bend and hydrophobic cluster involving D2.

OSCAR D1-D2 domain interface. (A) Comparison of D1-D2 interdomain angles among OSCAR, representative LRC receptors, and FcγRIII. D2 domains from OSCAR (magenta), p58-CL42 KIR (blue), GPVI (red), LILRB4 (gold), and FcγRIII (green) were superimposed to illustrate the relative positions of D1. For purposes of comparison, the degrees of rotation are defined such that at 0°, D1 would be doubled back and occupying the same position as D2 (see circle with arrows illustrating the clockwise rotation describing the relative positions of D1 domains). (B) Comparative views of the D1-D2 linker in FcαRI (top), GPVI (middle), and OSCAR (bottom). Conserved residues at the D1-D2 junction are shown as transparent spheres and color-coded according to their positions in the sequence alignment. Most LRC receptors have a Thr-Gly-Φ-Φ motif that creates a sharp bend in the D1-D2 linker sequence and packs the hydrophobic (Φ) residues after Gly against other hydrophobic residues in D2. In OSCAR, the mostly conserved Gly residue and the subsequent hydrophobic residue are replaced by 2 large, negatively charged Glu residues, sterically preventing formation of the sharp bend and hydrophobic cluster involving D2.

In OSCAR, the D1-D2 linker includes 2 nonconserved residues responsible for the unusual interdomain angle. Alignment of LRC family sequences reveals a consensus linker sequence of Φ-Φ-Φ-T-G-Φ-F/Y with 3 hydrophobic (Φ) residues and Thr at the end of D1, followed by Gly, another hydrophobic residue, then Phe/Tyr. The conserved Gly residue in most LRC receptors allows the main chain to turn sharply, packing the subsequent hydrophobic residues (eg, Leu-Tyr in FcαRI or Val-Phe in GPVI) against residues at the end of the G strand in D1 and in the WSXWS motif within the extended FG loop of D2, to form a small hydrophobic core at the D1-D2 interface (Figure 3B). In some cases, an additional residue (eg, FcαRI Phe-185) from the D2 WSXWS motif packs against the Gly linker residue, further stabilizing the turn configuration. In contrast, the linker sequence in OSCAR is LLVTEEL, with 2 large charged Glu residues in place of a Gly and Φ. The Glu-Glu motif precludes the tight main-chain turn and hydrophobic packing, resulting in only 626 Å2 of buried surface area in the OSCAR D1-D2 interface, compared with ∼900 to 1200 Å2 in other LRC receptors. Interestingly, 626 Å2 falls below the cutoff proposed for stable interdomain interfaces,18,19 suggesting that the D1-D2 junction in OSCAR may be more flexible than in other LRC receptors. Importantly, the structure of OSCAR bound to the consensus collagen THP (described in the next section) showed the primary collagen-binding site to be located on D2 and to require the atypical D1-D2 configuration to avoid steric clashes between the THP and D1 of OSCAR (supplemental Figure 2). Detailed comparisons of free and bound OSCAR to other collagen-binding LRC receptors are included in the supplemental Results.

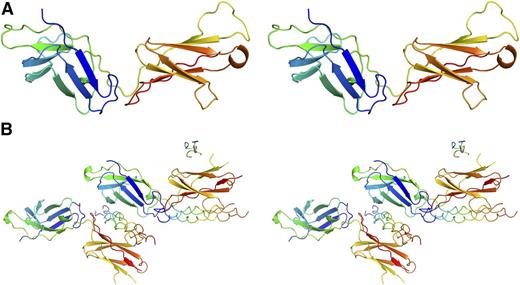

Crystal structure of OSCAR D1D2 in complex with the THP GPOGPAGFO indicates 2 collagen recognition sites

The structure of mammalian-expressed D1D2 bound to the DB316 THP was determined at 2.4 Å via molecular replacement using the apo-structure as the search model (Figure 4). Each asymmetric unit contains 2 copies of D1D2 and 2 full-length DB316 triple helices with well-resolved electron density. Incomplete density for a third DB316 was observed on a noncrystallographic symmetry twofold axis, but is presumed to be an artifact of crystal packing and will not be discussed further. A predominant feature of the complex is that the D1 and D2 domains each bind a DB316 THP, leading to a 2:2 stoichiometry in the asymmetric unit, contrasting with all previous structures of collagen receptors in complex with THPs (Figure 4B). A central copy of DB316 is held between D1 of 1 OSCAR and D2 of the second OSCAR, whereas D2 of the first OSCAR binds an additional copy of DB316, which itself interacts with D1 of a symmetry-related OSCAR. The central DB316 exhibits conventional triple-helical structure with its leading, middle, and trailing chains showing a 1-residue stagger. It is essentially straight, but slightly bent toward D2. The flanking GPO triplets adopt 72 symmetry, and although the central domain is less tightly assembled, relaxation to 103 symmetry is incomplete, which is not surprising because only the 3-residue AGF tract in DB316 deviates from model GPO polymers which attain canonical 72 symmetry. The DB316-D2 interface has a total buried solvent-accessible surface area of around 1500 Å2, compared with 870 Å2 for the DB316-D1 interface (Figure 5). The 2 peptides bound to the same OSCAR ectodomain form a dihedral angle of ∼70°. This indicates that simultaneous binding of D1 and D2 to the same collagen fiber, where the triple helices are essentially parallel, is unlikely (supplemental Figure 3).

Structures of OSCAR, free and bound to DB316 THP. Stereo view of OSCAR D1D2 structures rendered as cartoons. OSCAR D1D2 and DB316 are colored in “chainbow” scheme, with the N terminus blue and the C terminus red. (A) Apo-structure. (B) DB316-bound OSCAR D1D2.

Structures of OSCAR, free and bound to DB316 THP. Stereo view of OSCAR D1D2 structures rendered as cartoons. OSCAR D1D2 and DB316 are colored in “chainbow” scheme, with the N terminus blue and the C terminus red. (A) Apo-structure. (B) DB316-bound OSCAR D1D2.

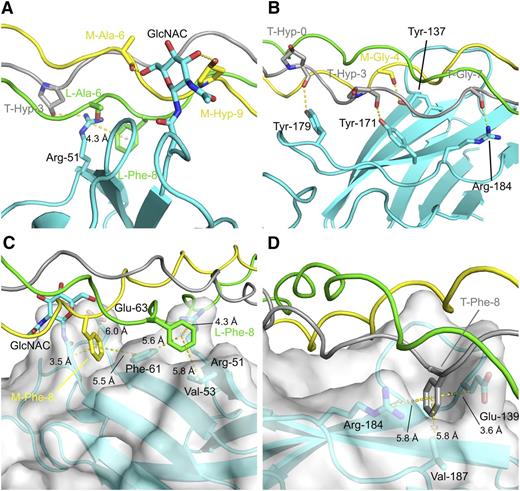

Molecular details of the OSCAR:THP-binding sites. Hydrophilic interfaces between DB316 and OSCAR D1 and D2, panels A and B, respectively; hydrophobic interfaces with semitransparent surfaces between DB316 and OSCAR D1 and D2, panels C and D, respectively. Protein and peptide are shown in cartoon, whereas residues involved in hydrophilic or hydrophobic interactions are emphasized by rendering as sticks. OSCAR ectodomain is colored cyan whereas leading, middle, and trailing strands of DB316 are colored green, yellow, and gray, respectively. Hydrogen bonds and distances (labeled and measured in Å) from center of phenylalanine benzyl rings are indicated by yellow dotted lines.

Molecular details of the OSCAR:THP-binding sites. Hydrophilic interfaces between DB316 and OSCAR D1 and D2, panels A and B, respectively; hydrophobic interfaces with semitransparent surfaces between DB316 and OSCAR D1 and D2, panels C and D, respectively. Protein and peptide are shown in cartoon, whereas residues involved in hydrophilic or hydrophobic interactions are emphasized by rendering as sticks. OSCAR ectodomain is colored cyan whereas leading, middle, and trailing strands of DB316 are colored green, yellow, and gray, respectively. Hydrogen bonds and distances (labeled and measured in Å) from center of phenylalanine benzyl rings are indicated by yellow dotted lines.

In the D2 site, 4 triplets (GPOGPOGPAGFO) on the middle and trailing chains of DB316 sit in a fitted groove formed by the curvature of the C′CFG β sheet and adjoining loops of D2. Tyr-137, Tyr-171, Tyr-179, and Arg-184 delineate the bottom of the groove and form a concerted group of hydrogen bonds to main-chain carboxyl groups of trailing-strand Hyp-0 (in the N-terminal flanking sequence), trailing-strand Hyp-3, middle-strand Gly-4, and trailing-strand Gly-7 on DB316 (Figure 5). The substitution of Hyp-3 of all 3 peptide chains with Ala introduces a local relaxation of helical twist, possibly directing its carbonyl group to an unfavorable position for hydrogen bonding. The benzyl ring of trailing strand Phe-8 is close enough (4.1 Å) to support a weak cation-π interaction with Arg-184. Additionally, the trailing strand Phe-8 is fitted into a hydrophobic pocket formed by Val-187 (5.8 Å), the hydrophobic stems of Glu-139 (3.6 Å) and the aromatic ring of Tyr-137 (5.6 Å). This fits with the finding that the Phe-8-Ala substitution in the GPOGPAGFO consensus peptide reduced Fc-tagged OSCAR ectodomain binding.4 In the D1 site, residues from the B, E, and D β strands contact the leading and trailing strands of DB316. Arg-51 on D1 forms both a hydrogen bond to the side-chain hydroxyl group of trailing Hyp-3 and contacts the leading strand Phe-8, 3.5 Å away, via a cation-π interaction. Again, this fits with the finding that Hyp-3-Ala substitution in the GPOGPAGFO peptide completely abolished Fc-tagged OSCAR ectodomain binding. The N-linked monosaccharide GlcNAc also contacts the middle chain, but from the opposite D2 side of DB316. It forms hydrogen bonds to the middle strand, to the Hyp-9 hydroxyl group, and to the main-chain carbonyl group of Ala-6. Although OSCAR N-glycosylation may play a minor role in binding collagen, our data indicated that bacterially expressed and glycosylated D1D2 bound collagen peptides similarly (Figure 1C). Phe-8 residues of both leading and middle chains are buried in pockets defined mostly by hydrophobic residues in D1, unlike D2. The leading strand Phe-8 sits inside the pocket formed by Val-53 (5.8 Å) and Phe-61 (5.6 Å) along with its cation-π interaction partner, Arg-51. Middle-strand Phe-8 also fits into the pocket near Phe-61 (5.5 Å) and the aliphatic stems of Asn-23 and Glu-63. Taken overall, the D2 groove seems to be the major binding site for DB316, judged by total buried surface area and extent of hydrogen bonding, whereas the D1 groove serves as an alternative minor site for peptide association.

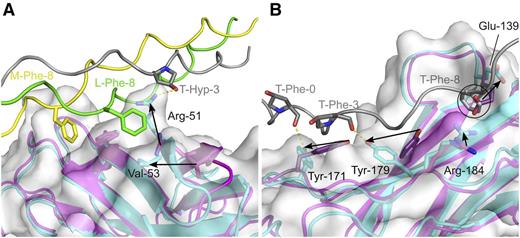

Conformational change of OSCAR D1D2 upon THP binding

Moderate conformational changes occur in OSCAR D1D2 upon binding DB316 (Figure 6). The C′ β-strand in D1 of free OSCAR shifts position to form the D strand in the ABED β sheet upon binding to DB316 THP (Figure 2B). This new D strand, residues Arg-51 to Ser-54, is better positioned to interact with the peptide. In the apo-structure, the side chain of Arg-51 is directed almost parallel to the peptide, rather than toward the crevice between Hyp-3 and Phe-8 on DB316 in the complex. Although the position of D1 Phe-61, between the leading- and middle-strand Phe-8 residues of DB316, is largely unchanged upon peptide binding, the distant Val-53 is rearranged much closer to the leading-strand Phe-8 (moving from 8.6 Å to 5.8 Å away), allowing Val-53 to delineate 1 edge of the hydrophobic peptide-binding pocket. This pocket does not exist in the apo-structure and is created upon interaction with the THP. It is worth noting that the other hydrophobic pocket that accommodates the middle-strand Phe-8 is present in both apo- and complex structures, presenting a preexisting surface on D1 for DB316 docking.

Conformational changes in OSCAR upon THP binding. Conformational changes in (A) OSCAR D1 and (B) OSCAR D2 upon binding DB316, shown by alignment of apo- and DB316-bound structures. The free OSCAR ectodomain is colored magenta; the structure of DB316-bound OSCAR ectodomain is colored cyan with its semitransparent surface in white; leading, middle, and trailing strands of DB316 are colored green, yellow, and gray, respectively. Leading and middle stands of DB316, which are not involved in binding OSCAR D2, are removed in panel B for clarity. Spatial relocation of interfacial residues are indicated by black arrows. The steric clash of free OSCAR Glu-139 with trailing chain Phe-8, when superimposing apo- and bound- structures, is indicated by a circle.

Conformational changes in OSCAR upon THP binding. Conformational changes in (A) OSCAR D1 and (B) OSCAR D2 upon binding DB316, shown by alignment of apo- and DB316-bound structures. The free OSCAR ectodomain is colored magenta; the structure of DB316-bound OSCAR ectodomain is colored cyan with its semitransparent surface in white; leading, middle, and trailing strands of DB316 are colored green, yellow, and gray, respectively. Leading and middle stands of DB316, which are not involved in binding OSCAR D2, are removed in panel B for clarity. Spatial relocation of interfacial residues are indicated by black arrows. The steric clash of free OSCAR Glu-139 with trailing chain Phe-8, when superimposing apo- and bound- structures, is indicated by a circle.

Although conformational change in D2 does not occur to the same extent as in D1, rearrangement of several crucial side chains is apparent. The main chain atoms of Tyr-171 and Tyr-179 can be essentially superposed in the apo- and complex structures, but their side chains adopt different rotamers upon peptide binding. DB316 attracts the hydroxyl groups of Tyr-171 and Tyr-179 to closer positions more favorable for hydrogen bonding. Tyr-137 is also slightly dislocated by DB316, becoming closer to the carboxyl group of Gly-4 on the middle chain, as also occurs for Arg-184 and trailing-strand Gly-7. Hydrophobic interactions also cause a major repositioning of Glu-139 upon DB16 binding. The edge of the pocket for trailing-strand Phe-8 is then constituted by the redirected Glu-139 side chain, which would otherwise create a steric clash with the Phe-8 aromatic ring. Overall, substantial conformational changes, especially in the side chains of the interfacial residues, occur in both D1 and D2 to better accommodate DB316.

Solid-phase and solution binding assays suggest D2 as the major collagen-binding site on OSCAR

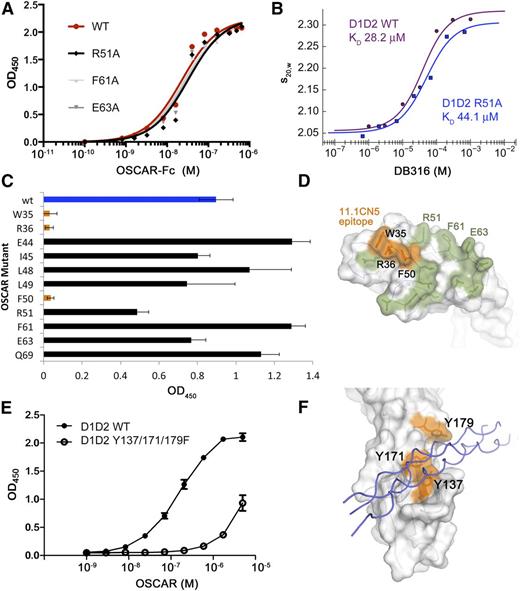

Initial solid-phase plate-binding experiments were conducted on wild-type (WT) and mutant variants of an OSCAR-Fc fusion using either acid-solubilized human placental collagen I, bovine collagen II, or anti-OSCAR antibodies. WT OSCAR-Fc bound to soluble collagens I or II with high avidity (EC50 [50% effective concentration] of 11.3 nM or 18.9 nM, respectively). Alanine scanning mutagenesis was carried out on 15 residues in OSCAR D1, including regions comprising the reported collagen-binding sites of both GPVI and LAIR-1 (Figure 7A; supplemental Table 4). Despite the near-complete coverage of the upper surface of D1, none of the mutant OSCAR-Fc proteins showed significant loss of affinity for immobilized collagen. EC50 values ranged from 8.0 nM to 22.5 nM; each mutant showed less than a twofold difference from WT OSCAR-Fc. These mutations included R51A, F61A, and E63A, residues observed in the D1-binding site for DB316 described in Figure 5C.

Binding and mutagenesis assays reveal D2 as the primary THP-binding site. (A) Solid-phase plate-binding assay to solubilized human placental collagen I showing WT OSCAR-Fc and 3 of the alanine point mutants in the D1 THP site. All other D1 mutants showed nearly identical binding curves. (B) Solution-phase binding assay between monomeric WT D1D2 or R51A-D1D2 and DB316 analyzed by sedimentation velocity AUC. Weight-averaged values of s20,w plotted vs DB316 concentration were fitted to a single-site binding equation. (C) Binding of WT and mutant OSCAR-Fc proteins to immobilized 11.1CN5, a nonblocking anti-OSCAR mAb. (D) Surface diagram of OSCAR D1, showing the epitope for 11.1CN5 that is composed of residues Trp-35, Arg-36, and Phe-50, which overlay the D1 region of LAIR-1 implicated in collagen binding. All other tested alanine mutations are shown in green; none caused a significant loss in affinity for 11.1CN5. (E) Solid-phase binding assay with immobilized THP DB80, comparing the affinity of monomeric WT D1D2 and a triple Tyr-to-Phe mutant that targets the D2 THP-binding site observed in the OSCAR complex. The triple mutant showed 50-fold decreased affinity for DB80, confirming that OSCAR D2 contains the primary binding site for the collagen consensus sequence. (F) Surface diagram of OSCAR D2, showing the location of the residues in the triple mutant (orange) in relation to the DB316 THP (blue coils) observed in the crystal structure.

Binding and mutagenesis assays reveal D2 as the primary THP-binding site. (A) Solid-phase plate-binding assay to solubilized human placental collagen I showing WT OSCAR-Fc and 3 of the alanine point mutants in the D1 THP site. All other D1 mutants showed nearly identical binding curves. (B) Solution-phase binding assay between monomeric WT D1D2 or R51A-D1D2 and DB316 analyzed by sedimentation velocity AUC. Weight-averaged values of s20,w plotted vs DB316 concentration were fitted to a single-site binding equation. (C) Binding of WT and mutant OSCAR-Fc proteins to immobilized 11.1CN5, a nonblocking anti-OSCAR mAb. (D) Surface diagram of OSCAR D1, showing the epitope for 11.1CN5 that is composed of residues Trp-35, Arg-36, and Phe-50, which overlay the D1 region of LAIR-1 implicated in collagen binding. All other tested alanine mutations are shown in green; none caused a significant loss in affinity for 11.1CN5. (E) Solid-phase binding assay with immobilized THP DB80, comparing the affinity of monomeric WT D1D2 and a triple Tyr-to-Phe mutant that targets the D2 THP-binding site observed in the OSCAR complex. The triple mutant showed 50-fold decreased affinity for DB80, confirming that OSCAR D2 contains the primary binding site for the collagen consensus sequence. (F) Surface diagram of OSCAR D2, showing the location of the residues in the triple mutant (orange) in relation to the DB316 THP (blue coils) observed in the crystal structure.

To further test the role of D1 in collagen binding, both nonblocking and blocking anti-OSCAR monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were tested in a solid-phase binding assay. The nonblocking mAb 11.1CN5 showed near-complete loss of binding to W35A, R36A, and F50A OSCAR-Fc mutants, revealing the 11.1CN5 epitope to be located on the membrane-distal surface of D1 (Figure 7C-D). Four different mAbs that block OSCAR binding to collagen were also tested, but none of the OSCAR-Fc D1 mutants had a significant effect on binding. Taken together, these solid-phase binding assays suggest that the D1 binding site for DB316 THP is a weak secondary site, not the primary site of engagement.

The experiments conducted with Fc-OSCAR binding to native collagen mimic cell-surface OSCAR binding to its natural ligand, but their interpretation could be complicated by avidity effects and secondary binding sites. Thus, we conducted parallel binding experiments in solution using AUC to analyze the interaction of DB316 with monomeric D1D2, an R51A mutant of D1D2, and D1 alone, each expressed in HEK293EBNA cells. Both WT D1D2 and R51A-D1D2 were titrated with up to a 50-fold molar excess of DB316, and analyzed by sedimentation velocity AUC. Corrected weight-average sedimentation coefficients (s20,w) were plotted vs DB316 concentration and fitted to single-site binding curves using Sedphat to determine the relative binding affinities (Figure 7B). WT D1D2 bound with a KD of 28.2 μM, compared with 44.1 μM for R51A-D1D2. Furthermore, OSCAR D1 alone did not form a complex with up to a 16-fold molar excess of DB316. These data, using monomeric OSCAR variants in solution, are consistent with the OSCAR-Fc solid-phase binding assays and indicate that, unlike GPVI and LAIR-1, the primary collagen-binding site of OSCAR is not in D1.

Solid-phase binding assay confirms D2 as the major collagen-binding site on OSCAR

To confirm the role of D2 in collagen binding, solid-phase binding assays were conducted using immobilized THP DB80, containing the consensus motif GPOGPAGFO. The consensus THP was chosen in order to confirm the crystallographic data and avoid complications from secondary binding sites in native collagen. WT OSCAR D1D2 and a triple mutant (with D2 residues Tyr-137, Tyr-171, and Tyr-179 each replaced with phenylalanine) were used, both proteins expressed in HEK293EBNA cells. These data, shown in Figure 7E, indicate that the loss of the tyrosine hydroxyl groups in the triple mutant is sufficient to reduce the affinity for DB80 by about 50-fold. This provides unequivocal evidence that the primary collagen-binding site is that observed in the D2 domain (Figure 7F).

Discussion

Distinct THP-binding sites on collagen-binding immune receptors

The ectodomains of the known immunoglobulin superfamily collagen receptors, LAIR-1, GPVI, and OSCAR, consist of 1 or 2 immunoglobulin-like domains, with very different collagen recognition sites despite their structural homogeneity. GPVI binds most strongly to the model collagen-related peptide with sequence (GPO)10 and to a few Toolkit peptides (III-1, III-30, and III-40),14 which contain 1 or 2 GPO triplets. LAIR-1 also displays high affinity for III-30 and for a subset of imino acid–rich peptides, but binds III-1 and collagen-related peptide less tightly.12 In contrast, OSCAR binds a defined consensus recognition sequence, GXOGPXGFX, and the orphan motif GAOGASGDR,4 but its Toolkit-binding pattern barely overlaps with those of GPVI and LAIR-1. Structures of both receptors exist,20,21 but no THP complex is yet published. The LAIR-1 ectodomain has a single immunoglobulin fold, which aligns better to D1 of both GPVI and OSCAR than to D2. Mutagenesis and nuclear magnetic resonance titration indicated a patch of residues on the membrane-distal region of LAIR-1 that contact the THP,20 residing in a groove composed of strands C, C′, F, and the FG loop. Similarly, D1 of GPVI is implicated in collagen binding, although 2 nearby but distinct sites have been proposed. One site, consistent with mutagenesis studies implicating Val-34 and Leu-36 in collagen binding,22 is analogous to that identified on LAIR-1. The second proposed site, a groove on GPVI D1 located on the other side of the C′ strand closer to the D1-D2 interface, was identified by computational docking of a (GPO)5 THP, and was consistent with further mutagenesis data implicating Lys-41, Lys-59, Arg-60, and Arg-166.21,23,24

Thus, different binding sites have evolved in the different LRC collagen receptors. LAIR-1, and perhaps GPVI, binds the THP via a membrane-distal groove on D1. The same groove in OSCAR is obscured by its own FG loop, which would clash with a bound collagen helix. Thus, OSCAR D1 can only bind THP in a secondary site, the crevice between strands C′ and E, similar to the second potential binding site in GPVI described in the previous paragraph.21 Less solvent-accessible surface is buried in this OSCAR site compared with the major groove in LAIR-1, which explains the low affinity for DB316 suggested by our mutagenesis data. In contrast, the major THP-binding site on D2 is a locus unique to OSCAR among the known immunoglobulin superfamily collagen receptors. In GPVI, the sharp 85° D1-D2 angle would hinder binding of a THP to the analogous D2 site (supplemental Figure 2). Alignment of GPVI and OSCAR D2 domains highlights further detailed differences. Side chains of Trp-130 and Trp-161 extend into a similar groove present on GPVI D2, with an inter-indole ring distance of about 4.4 Å, forming a hydrophobic patch that excludes collagen. The absence of these tryptophans on OSCAR D2 opens its groove for ligation.

Specificity determinants of THP recognition by mammalian collagen-binding receptors

Several crystal structures have now been reported for complexes between collagen THPs and collagen-binding proteins, and certain recurring features of collagen recognition become apparent. The von Willebrand factor A3 domain,25 DDR2 (discoidin domain receptor 2) DS domain,26 and SPARC (secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich) FS-EC domain ΔαC27 recognize the same sequence, GPRGQOGVMGFO. The integrin α2 I domain binds the sequence, GFOGER,28 whereas the OSCAR consensus is GPOGPAGFO. A conserved feature is the presence of the large, hydrophobic phenylalanine residue, suggesting a common binding mechanism, discussed in detail in the supplemental Results. In OSCAR, both D2 and D1 sites contain pockets that accommodate Phe-8 side chains in DB316; similar Phe pockets are seen in other collagen receptors (supplemental Table 5). In contrast, no pocket for Phe is visible in the integrin α2 I domain–GFOGER complex,28 but instead, the aliphatic side chain of the conserved THP glutamate is inserted into a similar pocket formed by integrin residues and a coordinated divalent metal cation that can mitigate the energetic penalty of burying a charged residue. In general, a collagen THP presents limited surface area for interaction with a receptor when compared with a globular protein ligand. Thus, the presence of a large hydrophobic or charged residue within the collagen sequence provides a potential anchor that can be docked into specific pockets on the receptor’s surface to increase the buried surface area of the complex, improving both affinity and specificity for a particular receptor.

Implications for binding to collagen I

The THPs used here are homotrimeric, avoiding the complications of synthesis and interchain registration that apply when constructing analogs of α1α1α2 heterotrimeric collagens such as I and IV. Collagen I, the most abundant vertebrate collagen, is shown to bind OSCAR both here and in our previous report.4 OSCAR binds to the fibrillar collagens at 5 loci, defined by Toolkit mapping and confirmed by subsequent short THP synthesis (see supplemental Table 6 and supplemental Discussion). Three loci are conserved with α1(II) across the α1(I) and α2(I) chains, defining sites in collagen I where OSCAR can bind. Conservation of the fourth and fifth (containing the orphan GAOGASGDR motif) loci is partial: they appear specific to collagens III and II, respectively.

Potential mechanisms for cell capture by exposed collagen

Our structures reveal that the OSCAR D1-D2 linker lacks the sharp bend typical of other LRC receptors, and the interface between domains is small and perhaps unstable. This suggests interdomain flexibility that would allow D1 to probe the local environment for exposed ligand and to form an initial complex that can be replaced by the firmer D2-collagen interaction. This might be especially important in the circulation, where transient tethering would assist monocyte recruitment to sites of collagen exposure, a concept similar to the accepted model for platelet capture by immobilized von Willebrand factor/GPIb.29 This would also explain why evolution has preserved OSCAR D1 even though D2 contains the primary binding site. The concerted activity of both binding sites on OSCAR would lead to significant avidity, accounting for the higher apparent KD of WT monomeric D1D2 when binding to immobilized peptide (on biosensor or assay plate surfaces) compared with the affinity measured in solution by AUC. In contrast, dimerization of GPVI provides a similar avidity benefit during platelet–vessel wall interaction,30 but because the modulatory function of LAIR-1 in other immune cells will be required only subsequent to cell capture and OSCAR ligation, a single LAIR-1 domain will suffice. Elucidating these interactions will contribute to our understanding of cellular immunity and pathology, and will pave the way for therapeutic targeting of these receptors.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for advice from Drs Marko Hyvonen, Jean-Daniel Malcor, and Katherine Stott (Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge).

This work was supported by the Diamond Light Source, the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team of the Advanced Photon Source, and by grants from the British Heart Foundation (RG/09/003/27122) and the Wellcome Trust (094470/Z/10/Z) (R.W.F.); funds from the Ohio Eminent Scholar program (A.B.H.); Crystallographic X-ray Facility of University of Cambridge funds (D.Y.C.); and by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI) training grant T32-HL007382 (J.M.H.). L.Z. is supported in part by a grant from Jesus College, Cambridge. A.D.B. was funded by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship.

Authorship

Contribution: L.Z., J.M.H., J.L.C.M., and D.G.C. performed the study; D.B. synthesized peptides; A.D.B. provided antibodies and advice; D.Y.C. assisted with initial screening and optimization of crystal growth; M.B., L.Z., J.M.H., and D.G.C. solved and refined the structures; and L.Z., R.W.F., and A.B.H. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.D.B. and R.W.F. are coinventors on a US patent: US2013280273 (A1): Modulation of the Activity and Differentiation of Cells Expressing the Osteoclast-Associated Receptor. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Richard W. Farndale, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Downing Site, Cambridge CB2 1QW, United Kingdom; e-mail: rwf10@cam.ac.uk; and Andrew B. Herr, Division of Immunobiology, Center for Systems Immunology, and Division of Infectious Diseases, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229; e-mail: andrew.herr@cchmc.org.

References

Author notes

L.Z. and J.M.H. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Design of a consensus collagen triple-helical peptide. (A) Table of collagenous peptide sequences used in solid-phase binding experiments. Collagen Toolkit peptides are identified by their numbers from Toolkits II and III, whereas derivative peptides are identified by their laboratory reference numbers. The consensus motifs, GXOGPXGFX or GAOGASGDR, are shown in black or red font, and segments of sequence that surround them are shown in gray. Not shown are the N- and C-terminal flanking motifs, GPC[GPP]5- and -[GPP]5GPC-amide, which are present on each peptide. Gpp10 denotes the control, GPC[GPP]10GPC-amide. (B) Polarimetry data of peptide DB316, Acetyl-GPOGPOGPOGPAGFOGPOGPO-amide were collected from 10°C to 70°C (up to 50°C is shown) at a ramp rate of 1°C min−1 as described in the supplemental Methods. First derivative of the original optical rotation data were used to define the peptide Tm. (C) Solid-phase binding of recombinant OSCAR (ectodomain E coli– or HEK293EBNA-expressed, 0.1 µg per well) on the collagenous peptides listed in panel A. Each peptide/protein combination was tested in triplicate, as described in supplemental Methods, and the inert peptide, (GPP)10, and BSA were used as negative controls. Data shown are mean ± SEM. (D) Biosensor curves of increasing concentrations of E coli–expressed recombinant OSCAR ectodomain titrated onto SRU 96-well plate coated by DB80, NR338, II-26, as well as (GPP)10 as negative control. Each point was collected in triplicate, and each data set was fitted to a model of specific and nonspecific binding in GraphPad Prism. The nonspecific binding curves were then removed for clarity. (E) Analytical gel filtration of recombinant OSCAR ectodomain preincubated with DB316 in different molar ratios. Each curve was derived separately using a Superdex 75 10/300gl column, running at 0.2 mL per minute, as described in supplemental Methods, and superimposed into 1 figure. Bmax, maximum binding; deg, degrees; dOR/dT, rate of change of optical rotation with temperature; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; mAU, milli absorbance units; OD, optical density; PWV, peak wavelength; SEM, standard error of the mean.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/127/5/10.1182_blood-2015-08-667055/4/m_529f1.jpeg?Expires=1769087018&Signature=B7KD2WgfHn9uImlT2pIFpJBzl~qOpdMc7b5rPu2LDxpeoQE514djHGljxhyltSt~FO5vH-X2Wsx9KaEYyJcHS9KRCSlNuScNhun0eEPsJ3OT8T9x2aK4Etm0HhePS9IjpUv0CzadRV1dsymaPbTpTK4WLSU2oK4zweHOfIasgs4AORSInYnaA6edvLxM2D7q7Ufnl0Q3qLVLjKRcZy9toI7YIGSxb6qL5QVXZJHBq-vr6gQ5wgFvuDZD2PJ~uZMsqrQP~UGkzn70kJqBGiFqWAvS5QLXKTHQcJIXUtdT~556e-Q-SZwDYK2mZN25LrdEyImhtSJ4g2ylBY90i9RrKA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal