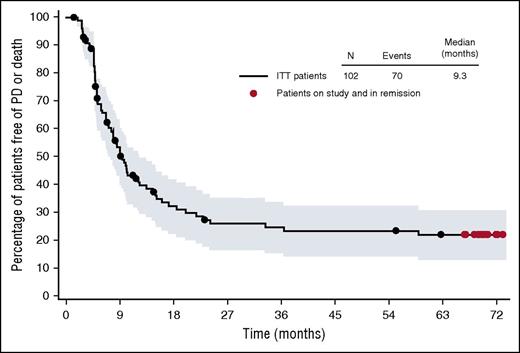

In this issue of Blood, Chen et al report the long-term follow up from a cohort of relapsed/refractory (R/R) Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients, who received single-agent brentuximab vedotin (BV) in a phase 2 pivotal trial, revealing a 5-year overall survival (OS) and 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 41% and 22%, respectively (see figure).1

PFS in 102 HL patients treated with BV. See Figure 1B in the article by Chen et al that begins on page 1562.

PFS in 102 HL patients treated with BV. See Figure 1B in the article by Chen et al that begins on page 1562.

The original report from this trial demonstrated an overall response rate of 75% and a complete response (CR) rate of 34%, leading to accelerated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for patients with R/R HL after hematopoietic autologous stem cell transplantation (auto-SCT) or failure of at least 2 prior therapies.2 BV, a novel antibody drug conjugate, has been described as a “game changer” in HL. Is BV living up to the hype? Of the 102 patients enrolled, 13 remain in continuous complete remission >5 years from registration. Of the 13 patients, 9 achieved this result having received only BV, whereas 4 received BV followed by hematopoietic allogeneic SCT (allo-SCT). Although 9% durability for BV alone may not seem like a noteworthy outcome, recall that these are generally young patients who had received 2 prior attempts at curative therapy (frontline therapy and auto-SCT). Given that the median age of the cohort was only 31, any degree of remission durability is meaningful. Long-term follow up also affords an opportunity to examine long-term toxicity. In the original publication on this cohort, 42% of patients experienced peripheral neuropathy (PN), of which 8% was grade 3.2 PN, even grades 1 to 2, is often a source of daily aggravation and frustration for patients. In this updated report, we learn that 88% of patients experienced either resolution (73%) or improvement (14%) in symptoms.

Do these results signify a significant therapeutic advance? Yes. Could similar results have been obtained with already available agents and strategies? Maybe, but patients likely would have endured more toxicity and morbidity to get comparable efficacy. Therefore, although the single-agent activity of BV is not a definitive solution for the majority of HL patients, it does provide an attractive option, which can provide a bridge to other therapies such as allo-SCT or the highly promising programmed death-1 (PD-1) and PD ligand-1 pathway inhibitors.3 What is sorely needed is a biomarker that could prospectively identify which patients are likely to be a long-term responder to single-agent BV. The authors report that the patients with sustained CR tended to be younger, have more extranodal disease, and a shorter interval from diagnosis to BV treatment. These are interesting observations, but given the very small numbers of patients, they are not reliable enough to guide practice.

As with any promising new drug, the real challenge is not in defining the single-agent activity but rather determining how to incorporate it into existing therapies. BV has since gained an additional FDA indication in HL, to be used as a consolidative therapy post–auto-SCT in high-risk patients. The ATHERA trial demonstrated that BV post–auto-SCT significantly improves PFS compared with placebo, although no impact on OS has been observed to date.4 Appropriately, BV is working its way up the treatment paradigm, being tested earlier and earlier in the disease course. For example, it has been used sequentially with ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide chemotherapy as a bridge to auto-SCT.5 Frontline phase 2 studies in early stage HL have now been completed and provide evidence that definitive trials should be undertaken.6 Most notably, an international phase 3 study comparing doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (ABVD) to doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine plus BV as frontline therapy for advanced stage HL (ECHELON-1 trial) has completed enrollment, and results are pending.7 This trial has the potential to change practice.

The data provided by Chen et al is both exciting and sobering. As with many novel agents, the remissions are not durable for the majority of patients. The median PFS is just 9.3 months, yet there is a tail to the PFS curve. What does one recommend to a 27-year-old patient who has relapsed after ABVD, relapsed again after auto-SCT, and has now responded to single-agent BV? Consolidation with allo-SCT and all of its associated risks, or do we gamble that our patient will be in the lucky 9% who achieves a durable remission with BV alone? The Chen et al article does not provide a clear pathway, but at least it provides the data, so we can engage in a thoughtful discussion with our patients.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.S.K. reports consulting for Seattle Genetics.