Key Points

All blood coagulation factors predominantly bind to a small “cap”-like region on procoagulant-activated platelets.

Their concentration in this small region promotes acceleration of the membrane-dependent reactions of coagulation.

Abstract

Binding of coagulation factors to phosphatidylserine (PS)-exposing procoagulant-activated platelets followed by formation of the membrane-dependent enzyme complexes is critical for blood coagulation. Procoagulant platelets formed upon strong platelet stimulation, usually with thrombin plus collagen, are large “balloons” with a small (∼1 μm radius) “cap”-like convex region that is enriched with adhesive proteins. Spatial distribution of blood coagulation factors on the surface of procoagulant platelets was investigated using confocal microscopy. All of them, including factors IXa (FIXa), FXa/FX, FVa, FVIII, prothrombin, and PS-sensitive marker Annexin V were distributed nonhomogeneously: they were primarily localized in the “cap,” where their mean concentration was by at least an order of magnitude, higher than on the “balloon.” Assembly of intrinsic tenase on liposomes with various PS densities while keeping the PS content constant demonstrated that such enrichment can accelerate this reaction by 2 orders of magnitude. The mechanisms of such acceleration were investigated using a 3-dimensional computer simulation model of intrinsic tenase based on these data. Transmission electron microscopy and focal ion beam-scanning electron microscopy with Annexin V immunogold-labeling revealed a complex organization of the “caps.” In platelet thrombi formed in whole blood on collagen under arterial shear conditions, ubiquitous “caps” with increased Annexin V, FX, and FXa binding were observed, indicating relevance of this mechanism for surface-attached platelets under physiological flow. These results reveal an essential heterogeneity in the surface distribution of major coagulation factors on the surface of procoagulant platelets and suggest its importance in promoting membrane-dependent coagulation reactions.

Introduction

The majority of biochemical reactions of blood coagulation do not occur in solution, but are rather surface-dependent, and take place on the membranes provided by cells and particles of blood and vasculature.1-3 Activated platelets are believed to be important contributors of the phosphatidylserine (PS)-rich surface for the procoagulant membrane-dependent reactions in thrombosis and hemostasis.4 They are heterogeneous, with the overwhelming majority of coagulation proteins binding to the single PS-exposing subpopulation of activated platelets.5-7 This subpopulation, which is generally characterized by a number of cell death markers and retains α-granule proteins attached to its surface (if thrombin is present in the activation mixture8,9 ) was termed procoagulant, necrotic, coated, or balloon-shaped platelets in different studies.10-15 It is likely to play an important role in supporting the assembly of the tenase and prothrombinase complexes, and ultimately in the whole thrombin generation process.

We recently found that major platelet adhesion mediators including fibrinogen and thrombospondin9 are not only retained on the procoagulant platelets, but are also predominantly concentrated in “caps,” which are specific structures on the surface of the procoagulant platelets. The same nonuniformity of surface distribution was recently reported for platelet-derived factor XIII (FXIII)16 and plasminogen.17 The “caps” are convexities of the balloon-shaped platelet membranes with a diameter of ∼2 μm (compared with 4 to 6 μm diameter of a “ballooned” platelet) present in the quantity of strictly 1 per procoagulant platelet.9 A recent report on the dynamics of platelet shape change during activation suggested that the “caps” are original bodies of platelets remaining after formation of the “balloons.”18 Because the function of the procoagulant platelets is likely to be the acceleration of coagulation reactions and not adhesion/aggregation,19 it seems logical to pose a question as to how coagulation proteins (in contrast to adhesion/fibrinolytic molecules) are distributed on these platelets.

In this study, we show that main blood coagulation factors are highly concentrated in the “caps” of procoagulant platelets, which could have significant implications for acceleration of the membrane-dependent reactions and spatial organization of the coagulation processes within arterial thrombi.

Methods

Reagents

The following materials were used: Annexin V-Alexa Fluor 647 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA); anti-FV/FVa antibody and anti-FVIII/FVIIIa antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA); FV, thrombin (Haematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT); FVIII (Kogenate FS) (Bayer Healthcare LLC, Berkeley, CA); FIXa, FX, FXa, and prothrombin (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN); 1,1-dihexadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate and fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR); prostaglandin E1 (MP Biochemicals, Irvine, CA); 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), bovine serum albumin, Sepharose CL-2B, apyrase grade VII, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and osmium tetroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); PS (Brain, Porcine) and PC (Brain, Porcine) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL); chromogenic substrate S-2765 (Chromogenix, Milano, Italy); lead citrate, by uranil acetate (SPI-Chem, West Chester, PA); 10 nm gold particles (Aurion, BioValley, France), Annexin V (BD Pharmingen, France), and recombinant hirudin (Transgene, Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France); and Horm fibrillar type-I collagen from equine achilles tendon (Nycomed, Zurich, Switzerland). Collagen-related peptide (CRP) was kindly provided by R. W. Farndale (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Blood collection and platelet isolation

Investigations were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under a protocol approved by the Federal Research and Clinical Centre of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Immunology Ethical Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all donors and patients. Blood was collected from healthy adult volunteers into 106 mM sodium citrate (9:1), and supplemented with apyrase (0.1 U/mL) and prostaglandin E1 (1 μM). Platelets were purified by gel filtration as described.7-9 Briefly, platelet-rich plasma was obtained with centrifugation for 8 minutes at 100 g. After supplementation with 106 mM sodium citrate (3:1), platelet-rich plasma was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 400 g, platelets were resuspended in buffer A (150 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM NaH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin; pH 7.4) and gel-filtered through Sepharose CL-2B. Platelets were activated at 5 × 107/mL for 15 minutes in the presence of 2.5 mM CaCl2 with 20 μg/mL CRP, or with 100 nM thrombin plus 20 μg/mL CRP.

Coagulation factor labeling

Dialyzed factors were supplemented with 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 9.0), 10 mg/mL FITC at a molar ratio dye/protein = 5, and incubated with stirring for 2 hours at 4°C. The reaction was stopped at 30 minutes incubation with 1.5 M hydroxylamine (pH 8.5). The mixture was centrifuged for 1 minute at 16 000 g in Sephadex G-25 spin columns to separate the conjugate from unreacted dye. The labeling degree was controlled by spectrophotometry, and activity retention was confirmed with an activated partial thromboplastin time-based clotting assay (Renam, Moscow, Russia).

Platelet-coagulation factor binding experiments

Glass coverslips (24 × 24 mm; Heinz Herenz, Hamburg, Germany) were cleaned with potassium dichromate, rinsed with distilled water, and dried. The cleaned coverslips were coated with 20 μg/mL fibrinogen in buffer A for 40 minutes at room temperature in a humid atmosphere, rinsed with distilled water, and assembled as parts of the flow chamber. For FVa binding assay, thrombin (100 nM) plus CRP (20 μg/mL)-activated platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were incubated for 5 minutes with specific antibodies to detect FV/FVa. For the FVIIIa binding assay, CRP (20 μg/mL)-activated platelets (5 × 104 cells/μL) were incubated for 5 minutes with 1 nM FVIII, and then incubated for 5 minutes with specific antibodies to detect FVIII/FVIIIa. For other factors or Annexin V, platelets (5 × 104 cells/μL) were activated with thrombin (100 nM) plus CRP (20 μg/mL). They were incubated for 5 minutes with FITC-Annexin V (23 nM), FITC-FIXa (60 nM), FITC-FX (250 nM), FITC-FXa (30 nM), or FITC-prothrombin (60 nM) in buffer A with CaCl2 (2.5 mM). Platelets were allowed to adhere in the flow chamber for 5 minutes and washed with buffer A containing CaCl2. Confocal images were captured using Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a Yokogawa spinning disc confocal device (CSU-X1; Yokogawa Corporation of America, Sugar Land, TX). Fluorescence intensity was converted to the mean number of molecules per platelet using a calibration curve obtained with green fluorescent protein-conjugated beads prepared and calibrated as described.20 Linearity of binding quantification was confirmed by control experiments using different ratios of labeled/unlabeled factors (see supplemental Figure 2, available on the Blood Web site).

Preparation of phospholipid vesicles

Synthetic phospholipid vesicles of 75% PC/25% PS or 95% PC/5% PS were prepared using a protocol recommended by Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) with minor modifications.21 Phospholipids were transferred to a round bottom flask and dried for 30 minutes under nitrogen. They were hydrated for 30 minutes in 20 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 for T >50°C. The resulting solution was subjected to a freeze-thaw cycle. Then, the solution was heated to T >50°C and vesicles were formed by extrusion through the membrane with a pore diameter of 800 nm. Vesicles were stored at +4°C and were used within 4 days of preparation.

FXa generation

Assays were performed in 96-well flat bottom polystyrene plates; 10 μM phospholipid vesicles of 5:95 (PS:PC ratio) or 2 μM phospholipid vesicles of 25:75 (PS:PC ratio), FIXa (1 nM), and FVIIIa (20 nM) in buffer with 2.5 CaCl2 were incubated at 37°C for 4 minutes. After FVIII activation with thrombin (10 nM) for 1 minute, D-phenylalanyl-L-prolyl-L-arginine chloromethyl ketone was added (2 μM). The reaction was initiated by the addition of FX (400 nM) and was stopped after 4 minutes by the addition of EDTA (final concentration = 10 mM). FXa concentration was determined from the rate of conversion of chromogenic substrate S-2765 (final concentration = 0.4 mM). The rate of substrate hydrolysis was monitored by absorbance at 405 nm using the ThermoMax Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Computer model of intrinsic tenase assembly and activation on the phospholipid membrane

The model was designed based on the binding and kinetic experimental data as described in Panteleev et al.21 Its development, design, and validation are outlined in supplemental Figure 1. The resultant model consisted of 7 partial differential equations, and described the interaction of FX and FIXa with phospholipid membranes, assembly of intrinsic tenase on their surface, and activation of FX by the complex. FVIIIa was assumed to be bound to the surface due to its small dissociation constant.22 The vesicle radius was considered to be 400 nm21 and the platelet radius assessed in the current study was 2000 nm as discussed later. The diffusion constants for all bound factors were assumed to be 0.001 μm2 per second. The formation of FX-FIXa complexes on the membrane was omitted to avoid circular fluxes in the model. The model was integrated using VCell software (http://www.vcell.org/).23 The corresponding Virtual Cell Model, 3D_platelet_cap, is available in the public domain at http://www.vcell.org/ under the shared username “agolomy.” The Fully Implicit Finite Volume Regular Grid integration method was used with mesh spatial step 0.04 to 0.1 μm.

Transmission electron microscopy

Platelets were activated with thrombin at 100 nM plus CRP at 20 mg/mL for 3 minutes and fixed with freshly prepared 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 hours. After rinsing 4 times with PBS (pH 7.4), the samples were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour. Then each sample was dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and embedded in Epon (Sigma-Aldrich). Ultrathin sections were produced using Ultracut E (Reichert, Vienna, Austria). The sections were stained with lead citrate followed by uranyl acetate and observed with the transmission electron microscope JEM-1400 (JEOL Tokyo, Japan).

Immunolabeling and focal ion beam-scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM)

For the immunogold experiments, Annexin was directly coupled to 10-nm gold particles as previously reported24 and incubated with activated platelets. Briefly, washed platelets (300 000/μL) were activated for 20 minutes with 1 U/mL thrombin plus 6 nM convulxin. Thrombin stimulation was stopped with hirudin (0.6 U/mL) and platelets were incubated for 2 minutes with Annexin V labeled with 10-nm gold particles (5 μg) or with free 10-nm gold particles as a control. The platelets were fixed for 1 hour by adding an equal volume of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3). The samples were then processed for FIB-SEM as described previously.25

Binding of Annexin V and coagulation factors to the “caps” in whole blood platelet thrombi

Human blood collected into hirudin was perfused at 1000 s−1 through glass microcapillaries coated with collagen at 200 μg/mL. Activated Annexin V-positive platelets were visualized by perfusing blood, in which platelets were observed by differential interference contrast (DIC) in the presence of FITC-conjugated Annexin V (5%). Imaging was performed with a Leica DMI 4000 B microscope (Leica Microsystems) using a Leica EL6000 fluorescent lamp and a ×40, 1.25 numerical aperture oil objective. Images were acquired with a Photometrics CCD camera (Cool-SNAP HQ Monochrome).

Results

PS is highly concentrated in the “caps” of procoagulant platelets

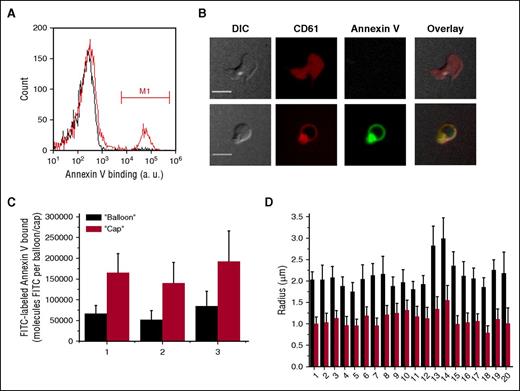

Washed gel-filtered thrombin-stimulated platelets form 2 subpopulations, only 1 of which binds Annexin V (Figure 1A). When the same samples were observed with confocal microscopy (Figure 1B), we did not see any significant binding of Annexin V to the nonprocoagulant spread platelets.5,21 In contrast, Annexin V binding to the balloon-shaped platelets was very pronounced. It could be seen that the “cap” appeared as a small bright region in the Annexin V channel, indicating that it is enriched with PS (supplemental Video 1).

Annexin V distribution on the surface of activated platelets. Platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were activated with thrombin at 100 nM for 15 minutes, incubated with Annexin V-FITC for 5 minutes, and analyzed using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. (A) Typical histograms of Annexin V binding to activate platelets in the absence (red line) or presence of EDTA (black line). Region marked M1 indicates the PS-positive platelets. (B) Distribution of Annexin V on the surface of activated platelets. Representative confocal images of DIC, FITC (green) fluorescence of Annexin V, and PE (red) fluorescence of CD61 are shown. Upper row is a typical nonprocoagulant platelet, and lower row is a typical procoagulant “ballooned” platelet. See also supplemental Video 1. Scale bars, 5 μm. (С) Quantitation of Annexin V-FITC binding to the “cap” and to the “balloon” for 3 different donors. The numbers below the bar graphs here and in the remaining figures are donor numbers. (D) Comparison between the sizes of the “caps” and the “balloons” for 20 donors. Results in (C-D) are mean ± standard deviation (SD), determined for at least 50 platelets in each experiment. PE, phycoerythrin.

Annexin V distribution on the surface of activated platelets. Platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were activated with thrombin at 100 nM for 15 minutes, incubated with Annexin V-FITC for 5 minutes, and analyzed using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. (A) Typical histograms of Annexin V binding to activate platelets in the absence (red line) or presence of EDTA (black line). Region marked M1 indicates the PS-positive platelets. (B) Distribution of Annexin V on the surface of activated platelets. Representative confocal images of DIC, FITC (green) fluorescence of Annexin V, and PE (red) fluorescence of CD61 are shown. Upper row is a typical nonprocoagulant platelet, and lower row is a typical procoagulant “ballooned” platelet. See also supplemental Video 1. Scale bars, 5 μm. (С) Quantitation of Annexin V-FITC binding to the “cap” and to the “balloon” for 3 different donors. The numbers below the bar graphs here and in the remaining figures are donor numbers. (D) Comparison between the sizes of the “caps” and the “balloons” for 20 donors. Results in (C-D) are mean ± standard deviation (SD), determined for at least 50 platelets in each experiment. PE, phycoerythrin.

To quantitate this, we integrated Annexin V fluorescence over the whole “cap” in 3 dimensions for each platelet. The same was done for the remaining surface of the “balloon” (Figure 1C). The small “cap” bound twofold more Annexin V than the large “balloon.” The sizes of the “cap” and of the “balloon” were compared (Figure 1D) for the same donors, and for several more, whose platelets were used for the coagulation factor-binding studies as shown later in this study. In all cases, the mean “cap” radius was ∼1 μm, and that of the “balloon” was 2 μm, suggesting a 2 × 2 = fourfold difference in size and an eightfold difference in volume. In any case, the local surface density of Annexin V on the “caps” appeared to be significantly higher than that on the “balloons.”

Spatial distribution of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors and triple-A domain cofactors on the procoagulant-activated platelet surface

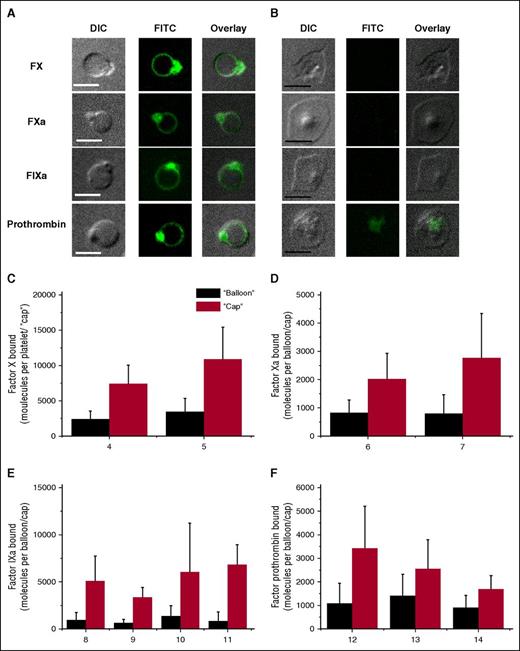

As a next step, we studied the binding of fluorescently labeled coagulation factors (FIXa, FXa, FX, and prothrombin) to the activated platelets using confocal microscopy (Figure 2). All demonstrated a pattern of distribution very similar to that of Annexin V: there were much more of them in the “caps” than in the “balloons” (Figure 2C-F). The difference was never less than twofold, and it was 10-fold for FIXa. With the interesting exception of prothrombin, the factors did not bind to the PS-negative subpopulation (Figure 2B).

Characteristics of FX, FXa, FIXa, and prothrombin distribution on the surface of procoagulant-activated platelets. Platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were activated with 100 nM thrombin plus 20 μg/mL CRP, incubated for 5 minutes with either 250 nM FX, 30 nM FХa, 60 nM FIXa, or 60 nM prothrombin, and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A-B) Representative confocal images of DIC, FITC (green) fluorescence of FX, FXa, FIXa, and prothrombin, and overlay are shown for procoagulant platelets (A) and nonprocoagulant ones (B). Scale bars, 5 μm. (C-F) The quantities of factor molecules bound to the “cap” (red bar) and to the “balloon” (black bar) are shown. Mean ± SD in (C-F) were determined for 30 to 70 procoagulant platelets analyzed in each experiment.

Characteristics of FX, FXa, FIXa, and prothrombin distribution on the surface of procoagulant-activated platelets. Platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were activated with 100 nM thrombin plus 20 μg/mL CRP, incubated for 5 minutes with either 250 nM FX, 30 nM FХa, 60 nM FIXa, or 60 nM prothrombin, and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A-B) Representative confocal images of DIC, FITC (green) fluorescence of FX, FXa, FIXa, and prothrombin, and overlay are shown for procoagulant platelets (A) and nonprocoagulant ones (B). Scale bars, 5 μm. (C-F) The quantities of factor molecules bound to the “cap” (red bar) and to the “balloon” (black bar) are shown. Mean ± SD in (C-F) were determined for 30 to 70 procoagulant platelets analyzed in each experiment.

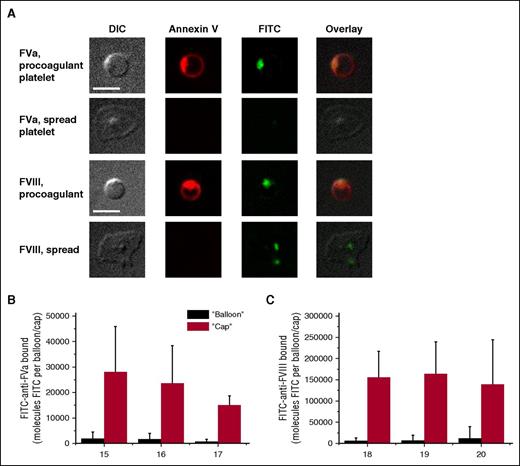

Similar experiments were performed for the cofactors of the vitamin K-dependent enzymes, FVa and FVIII (Figure 3). The inactive, pro-cofactor form of the latter was used because of the instability of the active form, and due to similarity in their binding mechanisms and parameters.21,26 Platelet-secreted FVa was retained on the PS-positive platelets only, with exceptionally predominant localization in the “cap.” In contrast, FVIII was observed on the PS-negative spread platelets as well, likely as a result of its carrier protein von Willebrand factor binding to GPIb. For the PS-positive platelets, the distribution of FVIII was exactly the same as for FVa. Control experiments of FVIII antibody binding in the absence of exogenous antibody and of FV antibody binding to the platelets from a previously characterized gray syndrome patient,27 confirmed that binding of the antibody to the negative population is at the level of nonspecific binding (supplemental Figure 3).

Characteristics of FVa and FVIII distribution on the surface of activated platelets. Platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were activated with 100 nM thrombin plus 20 μg/mL CRP (for FVa; we did not add thrombin in case of FVIII), incubated for 5 minutes with specific antibodies to detect FV/FVa and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A) Representative confocal images of DIC, and FITC (green) fluorescence of FV/FVa and FVIII/FVIIIa, and overlay are shown. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B-C) Integral fluorescence for the bound factors. Mean ± SD in (B-C) were determined for 30 to 70 procoagulant platelets analyzed in each experiment.

Characteristics of FVa and FVIII distribution on the surface of activated platelets. Platelets (5 × 104 μL−1) were activated with 100 nM thrombin plus 20 μg/mL CRP (for FVa; we did not add thrombin in case of FVIII), incubated for 5 minutes with specific antibodies to detect FV/FVa and imaged with confocal microscopy. (A) Representative confocal images of DIC, and FITC (green) fluorescence of FV/FVa and FVIII/FVIIIa, and overlay are shown. Scale bars, 5 μm. (B-C) Integral fluorescence for the bound factors. Mean ± SD in (B-C) were determined for 30 to 70 procoagulant platelets analyzed in each experiment.

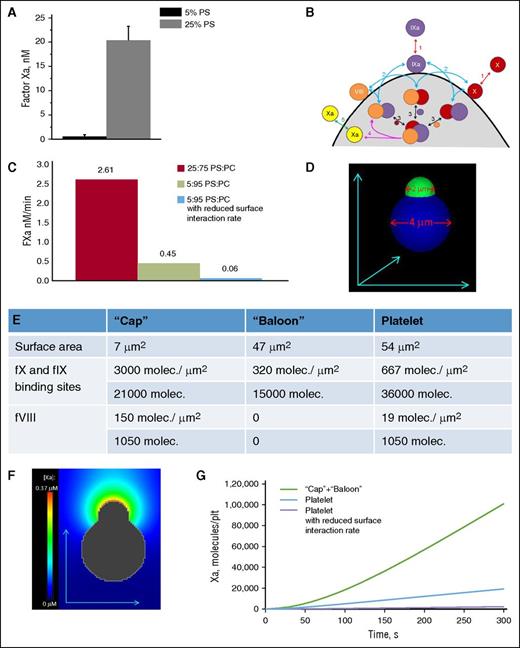

Importance of increasing local surface density of the coagulation factors: experiments

Although it is more or less accepted that acceleration of the membrane-dependent reactions is due to the locally increased concentrations of their components,28,29 it is not intuitively obvious what would be more advantageous for a specific membrane-dependent reaction in each case: a higher surface density or a larger surface area of the membrane? To obtain possible insight into the meaning of the nonhomogeneous distribution of coagulation factors on the activated platelet surface, we performed experiments in a purified system aimed to mimic the phenomena observed with platelets (Figure 4A). Specifically, we prepared 2 types of 800-nm lipid vesicles composed of PS/PC at the ratios of 25/75 and 5/95, and added FIXa, FVIIIa, and FX to both types of lipid vesicles while keeping the overall PS quantity constant (ie, we had 2 μM of high-surface density 25/75 lipids and 10 μM 5/95 lipids, and there was 0.4 μM of PS in both cases). The difference was huge. Activation of FX proceeded 50-fold more rapidly on the vesicles with less surface area and higher PS density (Figure 4A). This suggests that preferential concentration of the coagulation factors in the “cap” might serve the same function, and additional acceleration of tenase and prothrombinase by a couple of orders of magnitude.

Effect of bound coagulation factors’ surface density on FX activation. (A) The 25:75 and 5:95 PS/PC vesicles were incubated with FIXa (1 nM), FVIIIa (20 nM), and FX (400 nM) in buffer A with 2.5 mM CaCl2 while keeping the PS concentration the same. The reaction was stopped after 4 minutes by the addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 10 mM. Generated FXa was determined from the rate of conversion of chromogenic substrate S-2765 (final concentration, 0.4 mM). The rate of substrate hydrolysis was monitored by absorbance at 405 nm. Mean ± SEM are shown for n = 3 independent experiments. (B) Scheme of membrane-dependent reactions of the tenase complex assembling on the phospholipid surface. FX and FIXa are assumed to bind to specific sites on the membrane and compete for them (reaction 1). FVIII is assumed to be tightly bound to the membrane with the possibility of deactivation during experiment. Their pairwise membrane interactions (reaction 2) lead to the formation of the enzyme-cofactor-substrate complex (reaction 3) and FX activation (reaction 4). (C) Comparison of the velocity of FXa formation in the computer simulation similar in condition to the experiment in (A). To achieve the drop in the amount of formed FXa observed in the experiments, the rate constants of the on-membrane factors interactions were reduced 10-fold. (D-G) Computational model of platelets with a “cap” with characteristics similar to real platelets. (D) Initial distribution of FVIIIa and binding sites for FX and FIXa. (E) Parameters of FVIIIa, and binding sites for FX and FIXa on the model platelet. (F) FXa concentration around platelets with a “cap” after 30 seconds of FX activation; the initial concentrations of FX and FIXa were 160 nM and 30 pM, respectively. (G) Time course of FXa production for a platelet with a “cap,” a platelet with uniform distribution of FVIIIa and binding sites, and with the assumption of membrane-dependent reactions slowing for low PS content. Molec, molecule; plt, platelet; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Effect of bound coagulation factors’ surface density on FX activation. (A) The 25:75 and 5:95 PS/PC vesicles were incubated with FIXa (1 nM), FVIIIa (20 nM), and FX (400 nM) in buffer A with 2.5 mM CaCl2 while keeping the PS concentration the same. The reaction was stopped after 4 minutes by the addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 10 mM. Generated FXa was determined from the rate of conversion of chromogenic substrate S-2765 (final concentration, 0.4 mM). The rate of substrate hydrolysis was monitored by absorbance at 405 nm. Mean ± SEM are shown for n = 3 independent experiments. (B) Scheme of membrane-dependent reactions of the tenase complex assembling on the phospholipid surface. FX and FIXa are assumed to bind to specific sites on the membrane and compete for them (reaction 1). FVIII is assumed to be tightly bound to the membrane with the possibility of deactivation during experiment. Their pairwise membrane interactions (reaction 2) lead to the formation of the enzyme-cofactor-substrate complex (reaction 3) and FX activation (reaction 4). (C) Comparison of the velocity of FXa formation in the computer simulation similar in condition to the experiment in (A). To achieve the drop in the amount of formed FXa observed in the experiments, the rate constants of the on-membrane factors interactions were reduced 10-fold. (D-G) Computational model of platelets with a “cap” with characteristics similar to real platelets. (D) Initial distribution of FVIIIa and binding sites for FX and FIXa. (E) Parameters of FVIIIa, and binding sites for FX and FIXa on the model platelet. (F) FXa concentration around platelets with a “cap” after 30 seconds of FX activation; the initial concentrations of FX and FIXa were 160 nM and 30 pM, respectively. (G) Time course of FXa production for a platelet with a “cap,” a platelet with uniform distribution of FVIIIa and binding sites, and with the assumption of membrane-dependent reactions slowing for low PS content. Molec, molecule; plt, platelet; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Three-dimensional (3D) computer simulation of intrinsic tenase assembly on the platelet surface and the possible role of the “cap”

In order to obtain insight into the possible role of increased coagulation factor concentration in the “cap,” we used a detailed mechanism-driven computational model of intrinsic tenase (Figure 4B). When used to describe the experiments of Figure 4A, the model indicated that a 10-fold reduction of the rate constants of the on-membrane factors association is necessary to account for the observed drop in FXa formation with PS content (Figure 4C). The model was further expanded to simulate a whole procoagulant platelet with a “cap” (Figure 4D-G) and predicted that efficiency of the “cap” in FX activation should be by orders of magnitude higher than that of the rest of “balloon” (Figure 4G). These estimations support the possible role of coagulation factor concentration in the “caps” in the acceleration of clotting reactions.

Formation of the “caps”

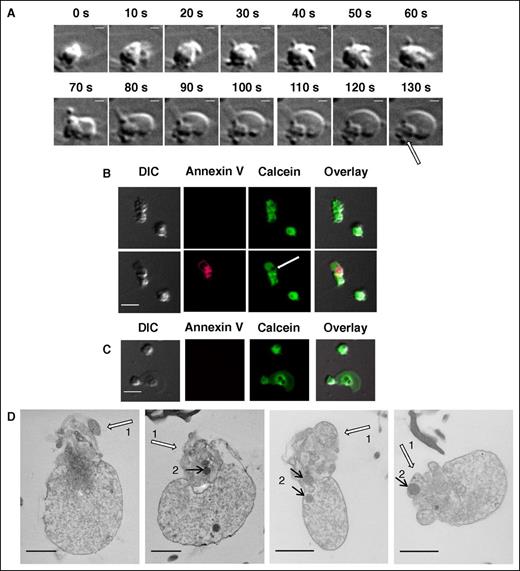

Real-time DIC microscopy of procoagulant platelet formation demonstrates how the “balloon” is blown out from the original platelet body, leaving a shrunken “cap” behind (supplemental Video 2; Figure 5A; the “cap” is indicated with an arrow). It is of interest, however, that the “caps” appear devoid of calcein in the calcein retention experiments (Figure 5B), as in the centers of nonprocoagulant platelets (Figure 5C). This is probably because these regions are crowded with densely packed organelles and a tubular system, and a thin green line of calcein around the empty center of the “cap” in Figure 5B suggests that there is some cytosol present.

Dynamics and inner structure of the “caps.” (A) Formation of the “balloon” and of the “cap” (indicated with arrow) in the procoagulant platelet at indicated times after activation. See also supplemental Video 2. Scale bars, 1 μm. (B) Distribution of calcein in procoagulant platelets at 5 minutes after the stimulation (upper row) and after the procoagulant platelet formation (at 20 minutes after the stimulation) (lower row). (C) The same for the nonprocoagulant platelets. (D) Transmission electron microscopic images of PS-positive platelets and of the “caps” indicated with white arrows (numbered 1). Discernible mitochondria are indicated with black arrows (numbered 2). Scale bars, 1 μm.

Dynamics and inner structure of the “caps.” (A) Formation of the “balloon” and of the “cap” (indicated with arrow) in the procoagulant platelet at indicated times after activation. See also supplemental Video 2. Scale bars, 1 μm. (B) Distribution of calcein in procoagulant platelets at 5 minutes after the stimulation (upper row) and after the procoagulant platelet formation (at 20 minutes after the stimulation) (lower row). (C) The same for the nonprocoagulant platelets. (D) Transmission electron microscopic images of PS-positive platelets and of the “caps” indicated with white arrows (numbered 1). Discernible mitochondria are indicated with black arrows (numbered 2). Scale bars, 1 μm.

The balloon-like parts of the procoagulant platelet membranes are clearly discernible in the confocal microscopy images as lines, so that these platelets appear in sections as a bright ring with an empty middle (Figures 1-3). In contrast, the “cap” appears as a single bright area. The estimations above relied on the assumption that the “caps” are also spheric membrane-covered objects. To confirm this, we used transmission electron microscopy. Figure 5D shows 4 representative transmission electron microscopy images of procoagulant platelets with “caps.” Although “balloons” appear essentially as membrane sacks filled with small debris, the “caps” seem to have a more complicated structure, with membrane folds and vesicles (or tubes, which are probably remnants of the open canalicular system), and with some organelles-like mitochondria trapped inside. Control experiments confirmed that the platelets with characteristic “capped” morphology were indeed procoagulant ones (supplemental Figure 4), and that this morphology appeared independently of Annexin V addition (supplemental Figure 5).

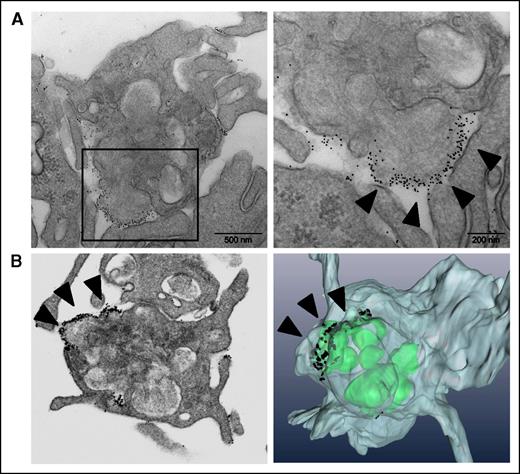

The ultrastructure of the “caps” of procoagulant platelets

To better characterize the “caps” and the binding of Annexin V to them, we used a 3D approach using FIB-SEM technology (Figure 6). This method allows a detailed visualization of entire platelets, thereby providing a complete 3D representation of the “caps” with respect to their position, their number, and connections to the cell surface. A 3D reconstruction of a “cap” analyzed by FIB-SEM is shown in Figure 6B. Typically, a single “cap” was present on the surface of a PS-positive platelet and was found to be in continuity with intracellular secretory compartments.

Immunogold Annexin V–labeling and FIB-SEM imaging of the PS-positive platelets, and of the “caps.” (A) Immunoelectron microscopy of Annexin V binding to platelets; the left panel shows increased magnification. (B) FIB-SEM imaging (left) and 3D-reconstruction (right) of the procoagulant platelets. The arrows indicate Annexin V on the platelet “cap.”

Immunogold Annexin V–labeling and FIB-SEM imaging of the PS-positive platelets, and of the “caps.” (A) Immunoelectron microscopy of Annexin V binding to platelets; the left panel shows increased magnification. (B) FIB-SEM imaging (left) and 3D-reconstruction (right) of the procoagulant platelets. The arrows indicate Annexin V on the platelet “cap.”

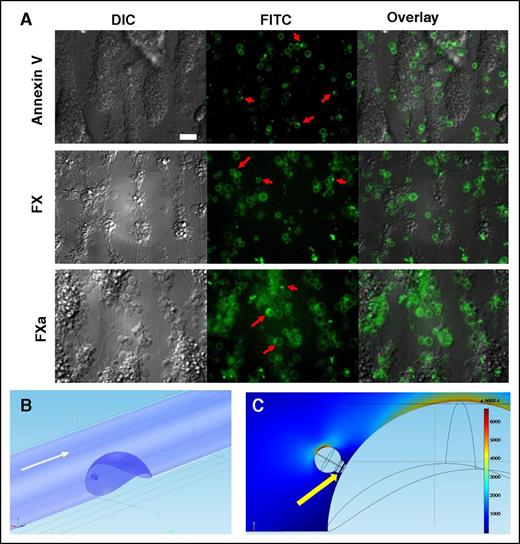

Presence of the “caps” in thrombi

To evaluate whether the “caps” appear in platelet thrombi formed under flow, and that these “caps” are also enriched with PS, we carried out experiments on thrombus formation in whole blood perfused over collagen. Following perfusion, the thrombi were stained for Annexin V, or FX, or FXa (Figure 7A), and visualized with epifluorescence microscopy. In all cases, procoagulant platelets were observed with “caps,” and they were located at the site of contact with the thrombus body, in line with a previous observation9 that the “caps” mediate attachment of procoagulant platelets to other cells.

Concentration of Annexin V, FX, and FXa on the “caps” in thrombi and its possible significance. (A) Typical epifluorescence microscopy images of platelet aggregates formed after perfusion of hirudinated human whole blood over immobilized collagen at 1000 s−1 (1500 s−1 for FX/FXa) for 5 minutes. Platelet aggregates were visualized using DIC and epifluorescent microscopy (×63 objective). Representative images of DIC and FITC (green) fluorescence of Annexin V, FX, or FXa are shown. Red arrows indicate typical PS-positive platelets with “caps.” Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) Design of a CFD model to evaluate blood flow within and outside of a “cap.” Hemispheric thrombus and procoagulant platelet at its surface are shown in blue. Flow direction is shown with white arrow. (C) Shear rates color map derived from CFD simulation for the central vertical cross-section of the vessel. Maximum shear rate is observed at the top of the “balloon” body of a procoagulant platelet, whereas the minimum values are inside the “cap” (indicated with a yellow arrow).

Concentration of Annexin V, FX, and FXa on the “caps” in thrombi and its possible significance. (A) Typical epifluorescence microscopy images of platelet aggregates formed after perfusion of hirudinated human whole blood over immobilized collagen at 1000 s−1 (1500 s−1 for FX/FXa) for 5 minutes. Platelet aggregates were visualized using DIC and epifluorescent microscopy (×63 objective). Representative images of DIC and FITC (green) fluorescence of Annexin V, FX, or FXa are shown. Red arrows indicate typical PS-positive platelets with “caps.” Scale bar, 25 μm. (B) Design of a CFD model to evaluate blood flow within and outside of a “cap.” Hemispheric thrombus and procoagulant platelet at its surface are shown in blue. Flow direction is shown with white arrow. (C) Shear rates color map derived from CFD simulation for the central vertical cross-section of the vessel. Maximum shear rate is observed at the top of the “balloon” body of a procoagulant platelet, whereas the minimum values are inside the “cap” (indicated with a yellow arrow).

In order to estimate the shear rates at the surface of a procoagulant platelet and its “cap,” we performed computational fluid dynamic (CFD) simulations of blood flow around the semispherical thrombus inside the microvessel (Figure 7B-C). The procoagulant platelet “balloon” was modeled as a sphere with a 2 μm radius, whereas the “cap” was treated as a hemispheric object with a 1 μm radius placed at the surface of the spherical body (ie, the “balloon”). A fragment of the open canalicular system supposed to exist in the “cap” was modeled as a cylindrical protrusion across the “cap” with a 0.1 μm radius (Figure 7C, yellow arrow). The procoagulant platelet was placed at the surface of the thrombus 10 μm above the vessel wall (Figure 7B), touching the “cap.” The microvessel was 40 μm in diameter, whereas the thrombus was modeled as a hemispheric protrusion inside the vessel lumen (hemisphere radius was 20 μm). Blood flow was described with Navier-Stokes equations solved numerically with COMSOL software. Shear rate at the surface of the microvessel outside the thrombus area was 1000 s−1. According to CFD results (Figure 7C), the maximum shear rate inside the “cap” was ∼70 s−1, whereas the maximum shear rate at the “cap” surface was ∼170 s−1. The maximum shear rate at the surface of the “balloon” body of a procoagulant platelet exceeded 6000 s−1, whereas the shear rate at the top of the spherical thrombus was ∼4700 s−1. Thus, this type of geometry results in a drastic decrease in shear rates observed at the surface of the “cap” as well as inside it.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated spatial distribution of several major blood coagulation enzymes, zymogens, and cofactors on the surface of activated procoagulant platelets. We showed that they are all highly concentrated on the “caps,” which are convex PS-rich regions on the surface of balloon-like procoagulant platelets that have a complex multifold structure. We hypothesize that this might serve 2 functions: (1) dramatic acceleration of the membrane-dependent reactions rate due to increased local surface density of the proteins, and (2) providing protection for coagulation factors from rapid flow.

The existence of concave “caps” on the procoagulant platelet “balloons” was described 2 years ago.9 We observed them in confocal microscopy images, where these structures demonstrated particularly high levels of adhesion molecules (fibrin and thrombospondin) and were found to mediate attachment of procoagulant platelets (that lack functional integrins10,17,19,30,31 ) to aggregates and thrombi. Since then, it has been reported that platelet-derived FXIIIa and plasminogen are also mostly associated with platelets in the “cap” regions, and not uniformly throughout the cell surface.16,17 All these molecules (thrombospondin, FXIIIa, and plasmin) can bind fibrin, which explains their enrichment in the “caps.” The data of the present study expand this phenomenon: all coagulation factors that can bind to PS-containing membranes are also concentrated in the same “caps” of procoagulant platelets. This is difficult to explain by the fibrin-binding mechanism, with the probable exception of FVIII. A recent study by Gilbert et al suggested that fibrin could play a major role in the binding of FVIII to platelets.32

The mechanism of the enhanced binding of vitamin K-dependent proteins in the “caps” requires additional research. Transmission electron microscopy images indicate that “caps” have a complicated surface structure, with probable tubes and folds. FIB-SEM experiments indicate that the surface of the “caps” is continuous. The data of the present study (the presence of organelles in the “caps” and not “balloons,” nonretention of calcein in their centers, and the dynamics of “balloon” formation) agree with the observation by Agbani et al18 that “caps” are remnants of platelets that have undergone cell death and shrinking, whereas “balloons” are just inflated parts of a platelet membrane. In this case, higher PS levels in the “caps” could be due to the release of granules with a high PS content in their membranes.33

Nevertheless, the binding of blood coagulation factors to these membranes allows them to get into close proximity of each other, which could promote their interaction. “Caps” are not the only place of their binding; for many, there is some interaction with the “balloon” as well. For example, ∼8000 molecules of FX bind to the “cap” and ∼4000 molecules bind to the “balloon”-like part when FX is added at 250 nM. However, given the much smaller size of the “cap,” the factors become greatly concentrated. It is known from earlier theoretical and experimental studies that a decrease of the phospholipid surface area could accelerate a membrane-dependent reaction. Here, we used a purified system to directly demonstrate that improvement of binding to a small area like that of a “cap” can accelerate a membrane-dependent reaction by 2 orders of magnitude. Computer simulations of the tenase assembly and functioning on the “caps” confirm this suggestion. It is notable that, not only do the membrane-dependent reactions occur only on a small subset of all platelets, it also restricts them to a small portion of such platelets.

Our hypothesis stands in contrast to the suggestion by Agbani et al18 that “balloons” are formed to promote coagulation by providing additional surface for the assembly of the membrane-dependent complexes. It should be noted however, that the data of both studies complement each other, and that the difference only relies in the interpretation of each study. Even the evidence18 that defective ballooning inhibits thrombin formation is in line with our hypothesis: without ballooning, the “caps” are probably not sufficiently decreased in size, so it is natural that the inhibition of “balloons” downregulates thrombin generation. Our experimental data and computer simulations clearly show that membrane-dependent reactions do not need additional surface to proceed: when binding density is increased and the surface is decreased, the reaction rate dramatically increases. This conforms with previous reports for tenase and prothrombinase,34 and with the overall concept of membrane-dependent reaction acceleration as a result of local concentration and reduction of dimensionality.28

An alternative, not necessarily excluding, explanation is that the “caps,” located in thrombi under the “balloons” (because the “caps” mediate adhesion and aggregation of procoagulant platelets) and having a complex structure, are better suited for “hiding” coagulation factors from blood flow that would otherwise remove active enzymes, thereby disrupting fibrin formation and leading to an embolism downstream instead. If the “caps” are indeed original platelets with some remnant of an open canalicular system, such tubing can be a perfect “hiding” place. We were able to observe the “caps” in arterial thrombi in vitro, as well as an increase of Annexin V and coagulation factor concentration in them. Curiously, we recently reported that procoagulant platelets can be disrupted by flow (due to their lack of functional cytoskeleton), but that the “caps” remain attached.35 Additional investigations are required to obtain intravital evidence of “cap” formation during thrombosis and its distribution of coagulation factors. However, one can speculate that procoagulant platelets in vivo should be located in (or near) the zone36 of potently activated, secretory platelets: their formation requires significant activation, and they in turn, serve as a source of thrombin generation.

The data of the present study allow the speculative view of the “caps” as possible central elements in the functioning of procoagulant platelets, because in addition to their previously demonstrated critical role in procoagulant platelet attachment9 and fibrinolysis,16,17 it appears that all major processes of blood coagulation are also located there.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marie-Christine Alessi, Matthias Canault (Universite Aix-Marseille, France), and Alan Nurden (Hôpital Xavier Arnozan, France) for valuable discussions, and R. W. Farndale for providing CRP. The authors are also deeply grateful to Jean-Yves Rinckel (UMR-S949, EFS-Alsace, France) for his technical assistance.

This study was supported by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (14-14-00195). Electron microscopy was made possible through the Moscow State University Development Program (PNR5.13).

Authorship

Contribution: N.A.P. planned the research, performed all coagulation factor binding experiments, and analyzed the data; A.N.S. designed the model, performed computer simulations, and analyzed the data; Y.N.K. performed kinetic experiments; A.E. planned and analyzed the FIB-SEM experiments; N.R. performed flow chamber experiments with thrombi; D.Y.N. planned and analyzed flow chamber experiments and performed CFD; S.I.O. performed electron microscopy experiments and real-time confocal microscopy for movies; I.I.K. developed the methodology for electron microscopy and analyzed the data; C.G. and F.I.A. planned the research and analyzed the data; P.H.M. planned the research, analyzed the data, and edited the paper; and M.A.P. planned the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Mikhail A. Panteleev, Federal Research and Clinical Centre of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology and Immunology, 1 Samory Mashela St, Moscow 117997, Russia; e-mail: mapanteleev@yandex.ru.