Key Points

Weak stimulation favors the fusion of single granules with the platelet surface and stronger stimulation induces granule-granule fusion.

VAMP8 participates in single and compound exocytosis.

Abstract

Although granule secretion is pivotal in many platelet responses, the fusion routes of α and δ granule release remain uncertain. We used a 3D reconstruction approach based on electron microscopy to visualize the spatial organization of granules in unstimulated and activated platelets. Two modes of exocytosis were identified: a single mode that leads to release of the contents of individual granules and a compound mode that leads to the formation of granule-to-granule fusion, resulting in the formation of large multigranular compartments. Both modes occur during the course of platelet secretion. Single fusion events are more visible at lower levels of stimulation and early time points, whereas large multigranular compartments are present at higher levels of agonist and at later time points. Although α granules released their contents through both modes of exocytosis, δ granules underwent only single exocytosis. To define the underlying molecular mechanisms, we examined platelets from vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 (VAMP8) null mice. After weak stimulation, compound exocytosis was abolished and single exocytosis decreased in VAMP8 null platelets. Higher concentrations of thrombin bypassed the VAMP8 requirement, indicating that this isoform is a key but not a required factor for single and/or compound exocytosis. Concerning the biological relevance of our findings, compound exocytosis was observed in thrombi formed after severe laser injury of the vessel wall with thrombin generation. After superficial injury without thrombin generation, no multigranular compartments were detected. Our studies suggest that platelets use both modes of membrane fusion to control the extent of agonist-induced exocytosis.

Introduction

Platelet secretion plays an important physiological role by discharging a variety of molecules which contribute to most platelet functions, including adhesion, amplification of a developing thrombus, and wound repair. Platelets contain 3 types of secretory granules: dense granules (δ), α granules (α), and lysosomes (γ), which are defined by their contents, kinetics of exocytosis, and morphologies. Dense granules contain small molecules (adenosine 5′-diphosphate [ADP], calcium, and serotonin), α granules contain polypeptides (hemostatic factors, angiogenic factors, cytokines, growth factors, and proteases), and lysosomes contain hydrolytic enzymes (β-hexosaminidase and cathepsins).1-3 Granule formation occurs within the megakaryocyte through either biosynthesis or endocytosis of granule constituents.4,5 Tomographic electron microscopy reconstructions have shown different α granule shapes, including spherical, multivesicular, and tubular subtypes.6,7 Heterogeneity of the α granule contents has also been proposed on the basis of immunofluorescence studies showing the segregation of angiogenic factors (pro- and antiangiogenic) or proteins (synthesized and endocytosed) in distinct granule subsets. Functionally, it has been suggested that this organization facilitates the differential release of a subpopulation of α granules under specific stimulation.8-11 A study by Kamykowski et al12 nevertheless failed to demonstrate any pattern of distribution of angiogenic factors and proteins in a pairwise co-localization model. Furthermore, use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay microarrays to generate a global view of α granule secretion profiles revealed no thematic release of platelet contents, but instead suggested that cargo proteins are released with different kinetics depending on their solubility, the granule shape, and/or the granule-plasma membrane fusion routes.13-15

Exocytosis starts with the docking of a vesicle to the cell membrane, an event promoted by soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complexes. The SNAREs then lead to fusion between the granular/vesicular membrane and the plasma membrane, forming a fusion pore for discharge of contents.16 Platelets contain several SNAREs located on granules (VAMP2, -3, -7, -8) and on the plasma membrane (syntaxin2, -4, -7, -8, -11 and SNAP23, -25, -29).16-18 Studies of transgenic mice and in patients have shown that VAMP8, syntaxin11, and SNAP23 play major roles in normal platelet granule secretion.19,20 A recent report identified Munc13-4 as a calcium sensor for platelet secretion, which acts as a tethering factor and stabilizes the granules before and during membrane fusion.21 So far, little is known about the mechanisms regulating platelet fusion pores. Single-cell amperometry studies have revealed that dynamin-related protein (Drp1) is an important regulator of fusion pore formation and expansion, but the mechanisms involved remain to be established.22

The routes through which the contents of α and δ granules are released remain uncertain. Some reports favor a model in which the granules fuse directly with the peripheral plasma membrane or the membrane of the surface-connected open canalicular system (OCS).23-25 Others have suggested the formation of large intracellular vacuoles originating either from dilated OCS channels or through granule-to-granule fusion.26-29 Scanning transmission electron microscopy tomography reveals that α granules are not connected to the OCS but rather fuse with the plasma membrane via long, tubular connections called pipes.30 In general, these observations were made at a single time point and after stimulation with a single concentration of agonist. It is not known whether these fusion routes are dependent on the degree of platelet activation and/or the kinetics of platelet secretion. Until now, platelet exocytosis has been studied mainly by using conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM). With this technique, it is impossible to determine the precise shape and size of the secretory granules, their intracellular distribution, or their interactions with the surrounding membranes (OCS, plasma, and granule membranes) because the thin sections do not sample enough platelet volume.

The aim of this study was to investigate how platelet α and δ granules fuse with the plasma membrane to release their contents. We used the focused ion beam-scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM), an imaging approach based on the serial sectioning of entire platelets, which gives a 3D representation of the granules with respect to their shape, size, and connections to the cell surface. We characterized 2 modes of platelet exocytosis occurring in a time- and stimulation-dependent manner. Fusion of individual granules with the cell surface (single exocytosis) was the predominant form in moderately activated platelets and at early time points, whereas granule-to-granule fusion (compound exocytosis) became significant as platelets were more activated. We found that compound exocytosis occurred through the homotypic fusion of α granules and required high intraplatelet calcium. VAMP8 was found to play a key, but not required, role in both single and compound exocytosis. Dense granules released their contents through single exocytosis. The size of the fusion pores varied, the initial pores being relatively small (∼40 nm) and the later pores being larger (∼150 nm). This might regulate the release of different cargo molecules, depending on their size.

Methods

Detailed methods are described in the supplemental Data, available on the Blood Web site.

Platelet preparation

Platelets were isolated by centrifugation in the presence of prostaglandin I2 to prevent activation during preparation and were resuspended in Tyrode’s albumin buffer containing apyrase to preserve their responsiveness to ADP.31

Sample processing for FIB-SEM

Washed platelets were fixed directly in the aggregation cuvette after addition of the agonist and were incubated with 1% tannic acid for 1 hour to identify the granules that had undergone secretion. Samples were then prepared for FIB-SEM as described.32

FIB-SEM imaging

Tannic acid–stained platelets were imaged in the backscattering mode at 3 kV on an FEI Helios NanoLab scanning electron microscope. Images containing 2048 × 1768 pixels were acquired with a pixel size of 4.4 × 5.6 nm in the x-y plane. Samples were milled with the FIB (20 kV) at a thickness of 20 nm per section, allowing the OCS (diameter of >45 and <150 nm) and thin connections (length >100 nm) to be followed in the z dimension. Fine tethers might be missed in the axial direction but can be distinguished if they lie in an x-y plane. Large volumes were examined (20 × 20 × 20 µm), and a minimum of 150 platelets in 3 independent stacks were counted.

Results

Spatial organization of the granules and the OCS in unstimulated platelets

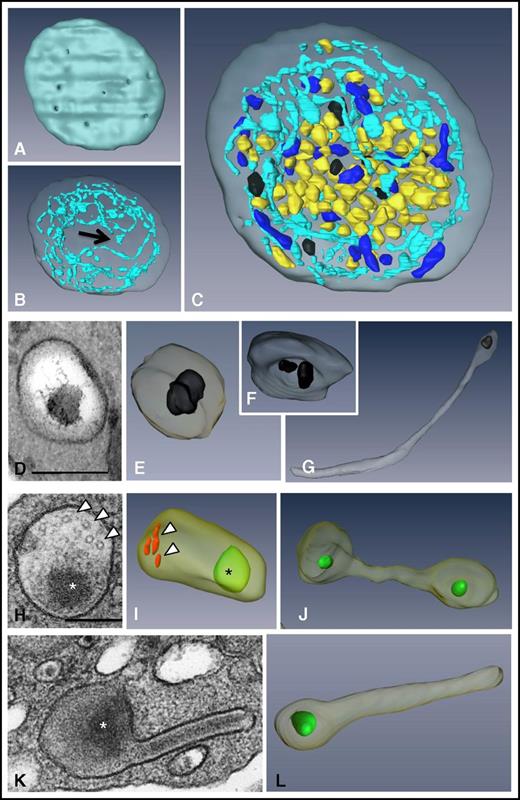

To visualize the 3D ultrastructure of the granules and the OCS in whole platelets, we used the FIB-SEM technology (Figure 1; supplemental Movie 1). We did not specifically investigate lysosomes in this study because they cannot be visualized without specific staining.33 The ability to image entire platelets (Figure 1C) allowed reliable counting of α and δ granules and mitochondria per platelet (41.6 ± 4.3, 8 ± 0.6, and 9.2 ± 0.9, respectively; n = 49; Table 1) and calculation of the volume of cytoplasm occupied by the OCS and α and δ granules (15.3 ± 1%, 8.4 ± 0.7%, and 1.3 ± 0.12%, respectively; n = 10). 3D reconstructions of the OCS showed long, branched tubules traversing the whole cytoplasm and forming numerous plasma membrane invaginations (27.2 ± 1.6 openings per platelet; n = 42) having a mean diameter of 41 ± 2 nm (n = 92) (Figure 1A-B). As previously reported,30 some closed canalicular systems (ie, not connected to the plasma membrane) were detected representing 5.5 ± 1.5% of the total canalicular systems (n = 12). Dense granules were easily distinguished through their typical dark central core and classical spherical geometry (Figure 1D-E). Occasionally, 2 dense bodies were found within a single δ granule (Figure 1F), and as previously demonstrated in whole mounts,34 tail-like extensions were observed (Figure 1G). Oval α granules were the most abundant and contained short von Willebrand factor (VWF) tubules 60 to 80 nm long (Figure 1H; in red in Figure 1I). Under our conditions of sample preparation, electron-opaque nucleoids30,34 were observed (in green in Figure 1I-J,L). Tubular and barbell-shaped granules were rare and were present at 1 to 4 copies per platelet in 32 ± 0.7% of platelets examined (Figure 1J-L; n = 100).

3D ultrastructure of unstimulated platelets using FIB-SEM. (A-C) 3D representations of a human platelet showing (A) the openings of the OCS at the platelet surface (gray), (B) the spatial arrangement of the OCS (blue) and of the closed canalicular system (arrow), and (C) the distribution of α granules (yellow), δ granules (black), and mitochondria (dark blue) in the whole platelet (see supplemental Movie 1 for an animation). (D-G) Images from TEM thin sections and (E-G) 3D FIB-SEM reconstructions of δ granules. These granules are mostly spherical, contain 1 or 2 characteristic electron-dense substructures, and may display a tail extension. (H-L) Images from TEM thin sections and 3D FIB-SEM reconstructions of α granules. (I) Oval α granules contain a nucleoid (*) shown in green and VWF (arrowheads) shown in red. Also shown are (J) a haltere and (L) tubular α granules that has developed a long extension. Scale bars, 200 nm.

3D ultrastructure of unstimulated platelets using FIB-SEM. (A-C) 3D representations of a human platelet showing (A) the openings of the OCS at the platelet surface (gray), (B) the spatial arrangement of the OCS (blue) and of the closed canalicular system (arrow), and (C) the distribution of α granules (yellow), δ granules (black), and mitochondria (dark blue) in the whole platelet (see supplemental Movie 1 for an animation). (D-G) Images from TEM thin sections and (E-G) 3D FIB-SEM reconstructions of δ granules. These granules are mostly spherical, contain 1 or 2 characteristic electron-dense substructures, and may display a tail extension. (H-L) Images from TEM thin sections and 3D FIB-SEM reconstructions of α granules. (I) Oval α granules contain a nucleoid (*) shown in green and VWF (arrowheads) shown in red. Also shown are (J) a haltere and (L) tubular α granules that has developed a long extension. Scale bars, 200 nm.

Quantification of the number of α and δ granules in unstimulated and activated whole platelets

| . | No. of seconds of stimulation . | No. of platelets . | α granules per platelet . | δ granules per platelet . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | P . | No. . | P . | |||

| Unstimulated platelets | 49 | 41.6 ± 4.3 | 8 ± 0.6 | |||

| ADP 5 µM | 7 | 8 | 40.6 ± 1.1 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | ||

| 30 | 13 | 38.7 ± 1.5 | 8.2 ± 0.6 | |||

| Thrombin 0.1 U/mL | 15 | 8 | 30.8 ± 1.4 | <.01 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | |

| 70 | 8 | 17.5 ± 1.2 | <.001 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | <.001 | |

| Thrombin 1 U/mL | 10 | 8 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | <.001 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | <.001 |

| 70 | 8 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | <.001 | None detected | ||

| . | No. of seconds of stimulation . | No. of platelets . | α granules per platelet . | δ granules per platelet . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | P . | No. . | P . | |||

| Unstimulated platelets | 49 | 41.6 ± 4.3 | 8 ± 0.6 | |||

| ADP 5 µM | 7 | 8 | 40.6 ± 1.1 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | ||

| 30 | 13 | 38.7 ± 1.5 | 8.2 ± 0.6 | |||

| Thrombin 0.1 U/mL | 15 | 8 | 30.8 ± 1.4 | <.01 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | |

| 70 | 8 | 17.5 ± 1.2 | <.001 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | <.001 | |

| Thrombin 1 U/mL | 10 | 8 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | <.001 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | <.001 |

| 70 | 8 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | <.001 | None detected | ||

Values are presented with standard error of the mean. P values were determined by using the two-way analysis of variance to compare each number of α and δ granules to unstimulated platelets.

Characterization of single and compound exocytosis

To analyze the spatial organization of the granules in activated platelets, we used a weak agonist, ADP (5 µM), and a strong agonist, thrombin, at 2 different concentrations (0.1 and 1 U/mL). ADP (5 µM) induced no exposure of P-selectin at the platelet surface, whereas 0.1 and 1 U/mL thrombin induced 65% and 95% of the maximal P-selectin exposure, respectively (supplemental Figure 1A). As expected, time-course studies of α and δ granule releases (platelet factor 4 [PF4] and serotonin, respectively) indicated that the extent of secretion was related to agonist potency: 1 U/mL thrombin induced massive release, whereas the granule release induced by lower thrombin concentrations was less (supplemental Figure 1B). Because secretion processes are accompanied by significant morphologic changes, we focused our FIB-SEM observations on 2 time points corresponding to the maximal turbidity (during shape change) and half-maximal aggregation as monitored by light transmission aggregometry (supplemental Figure 1B). To identify the granules connected to the extracellular space (ie, having undergone secretion), the platelets were stained with the electron-dense extracellular tracer tannic acid after fixation.

Exocytosis at maximal platelet shape change.

When platelets were stimulated with ADP (5 µM for 7 seconds), no granules were stained with tannic acid consistent with an absence of exocytosis (Table 1; in yellow in Figure 2Ai-iii). In platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin (15 seconds), a few granules were positive for tannic acid. 3D reconstructions indicated that each granule interacted independently with the plasma membrane (in red), a process commonly known as single exocytosis (Figure 2Aiv-vi; supplemental Movie 2). Accordingly, the number of remaining α and δ granules per platelet decreased by 1.4-fold (30.8 ± 1.3 and 5.8 ± 0.5, respectively; Table 1) confirming that both types of granules underwent single exocytosis events. After stimulation with 1 U/mL thrombin (10 seconds), a large decrease in the numbers of α and δ granules was observed (7.5 ± 0.9 and 1.3 ± 0.3, respectively; Table 1). They formed large tannic acid–positive intracellular granule aggregates with up to 10 granules clearly fusing with each other (Figure 2Avii-ix; supplemental Movie 3). This pattern of exocytosis is called compound exocytosis. We quantified 3 types of events: (1) platelets displaying no exocytosis, (2) single exocytosis, and (3) compound exocytosis (n >150 platelets in 3 independent experiments) and found that the mode of exocytosis correlated with the strength of the stimulation. Single exocytosis was predominant in moderately stimulated platelets whereas compound exocytosis was more frequent in strongly stimulated platelets. Fusion was evident with the morphologically recognizable OCS (arrows in Figure 2Av; supplemental Figure 2A) and with thin channels (arrows in Figure 2Aviii; supplemental Figure 2) providing small pores at the platelet surface 39 ± 1.1 nm in diameter (n = 197). These pores were visible in SEM images (Figure 2Cii).

3D organization of the granules in stimulated platelets. To study exocytosis, platelets were stimulated with ADP (5 µM) or thrombin (0.1 or 1 U/mL), fixed at time points corresponding to (A) shape change or (B) half-maximal aggregation, stained with tannic acid, and prepared for FIB-SEM. Tannic acid coats the cell surface, fills the OCS, and enters the granules undergoing secretion. Two images from FIB-SEM slices of stimulated platelets (right, detail of the granules) and a 3D reconstruction of stained granules (in red) and unstained granules (in yellow) are shown for each condition. Scale bars in the first column, 500 nm; scale bars in the second column, 200 nm. Images are representative of at least 3 different experiments. (A) Maximal platelet shape change. (i-iii) Platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 7 seconds). Note that single granules and OCS remained in separate compartments. (iv-vi) Platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 15 seconds. Some single granules are tannic acid–positive. (vii-ix) Platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. (*) Indicates stained aggregates of granules. Note that the connections with the platelet surface pass through narrow OCS channels (arrows), resulting in small pores at the cell surface. (B) Half-maximal aggregation. (i-iii) In platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 30 seconds), the granules remained unstained. (iv-vi) In platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 70 seconds, 2 pools of granules are visible. (vii-ix) In platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 70 seconds, the fused granules form large intracellular compartments (*) which are all in contact with the external space, creating large fusion pores at the platelet surface (arrows). Bar graphs represent the quantification of the exocytosis events (ie, no granular fusion [white bar], single granular fusion [gray bar], or granule-to-granule fusion [black bar], in response to different degrees of platelet stimulation and different time courses of activation). Three experiments were performed for each condition with >150 platelets in each case. Vertical bars indicate mean ± standard error of the mean. (C) Representative SEM images of (i) unstimulated platelets, (ii) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin and fixed at time points corresponding to shape change (15 seconds), and (iii) half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). The fusion pores are indicated with black arrows, and OCS openings are indicated with a white arrow. Scale bars, 1 µm. (D) Time course of α granule cargo release from platelets stimulated with 0.1 and 1 U/mL thrombin. At the indicated times (in seconds), thrombin stimulation was stopped with hirudin (100 U/mL), and platelets were immediately centrifuged at 16 000g for 5 minutes. The releasates were assayed for PF4 content (square), fibronectin content (triangle), and VWF activity (circle) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Each time point corresponded to 3 separate experiments.

3D organization of the granules in stimulated platelets. To study exocytosis, platelets were stimulated with ADP (5 µM) or thrombin (0.1 or 1 U/mL), fixed at time points corresponding to (A) shape change or (B) half-maximal aggregation, stained with tannic acid, and prepared for FIB-SEM. Tannic acid coats the cell surface, fills the OCS, and enters the granules undergoing secretion. Two images from FIB-SEM slices of stimulated platelets (right, detail of the granules) and a 3D reconstruction of stained granules (in red) and unstained granules (in yellow) are shown for each condition. Scale bars in the first column, 500 nm; scale bars in the second column, 200 nm. Images are representative of at least 3 different experiments. (A) Maximal platelet shape change. (i-iii) Platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 7 seconds). Note that single granules and OCS remained in separate compartments. (iv-vi) Platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 15 seconds. Some single granules are tannic acid–positive. (vii-ix) Platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. (*) Indicates stained aggregates of granules. Note that the connections with the platelet surface pass through narrow OCS channels (arrows), resulting in small pores at the cell surface. (B) Half-maximal aggregation. (i-iii) In platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 30 seconds), the granules remained unstained. (iv-vi) In platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 70 seconds, 2 pools of granules are visible. (vii-ix) In platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 70 seconds, the fused granules form large intracellular compartments (*) which are all in contact with the external space, creating large fusion pores at the platelet surface (arrows). Bar graphs represent the quantification of the exocytosis events (ie, no granular fusion [white bar], single granular fusion [gray bar], or granule-to-granule fusion [black bar], in response to different degrees of platelet stimulation and different time courses of activation). Three experiments were performed for each condition with >150 platelets in each case. Vertical bars indicate mean ± standard error of the mean. (C) Representative SEM images of (i) unstimulated platelets, (ii) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin and fixed at time points corresponding to shape change (15 seconds), and (iii) half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). The fusion pores are indicated with black arrows, and OCS openings are indicated with a white arrow. Scale bars, 1 µm. (D) Time course of α granule cargo release from platelets stimulated with 0.1 and 1 U/mL thrombin. At the indicated times (in seconds), thrombin stimulation was stopped with hirudin (100 U/mL), and platelets were immediately centrifuged at 16 000g for 5 minutes. The releasates were assayed for PF4 content (square), fibronectin content (triangle), and VWF activity (circle) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Each time point corresponded to 3 separate experiments.

Exocytosis at half-maximal aggregation.

In platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 30 seconds), the granules were centralized, remained single, and were unstained with tannic acid (Figure 2Bi-iii; Table 1). After stimulation with 0.1 U/mL thrombin (70 seconds), tannic acid staining revealed the presence of 2 pools of granules: an unstained pool located in the cell center composed of individual granules and a stained pool located peripherally composed of granule aggregates (Figure 2Biv-vi). Upon stimulation with 1 U/mL thrombin (70 seconds), granules were no longer present as single organelles (Table 1); all were fused together filling the entire cytoplasm with connection to the cell surface (Figure 2Bvii-ix). We quantified these events and found that the majority of platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin underwent compound exocytosis. These results indicated that the organization of the granules changes during the course of activation, with single exocytosis progressing to compound exocytosis. At lower thrombin concentrations (0.03 U/mL), only single exocytosis events were detected (supplemental Figure 3). We also observed that at this time point, the plasma membrane became the fusion target for multigranular compartments, and large pores were formed at the platelet surface (152 ± 4 nm; n = 164) (Figure 2Ciii).

Relationship between the size of the fusion pores and the release of small vs large cargo proteins.

To investigate whether the diameter of the fusion pores could influence the kinetics of secretion according to the cargo size, we performed time course experiments and quantified the release of PF4 (30 kDa), fibronectin (220 kDa), and VWF (20 × 103 kDa). In accordance with this hypothesis, we observed that in platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin, the release of PF4 was the most rapid, whereas fibronectin release was slower and VWF release was delayed. However, a higher concentration of thrombin (1 U/mL) induced rapid release of all 3 proteins with nearly complete release at the earliest time points (Figure 2D).

Granule-to-granule fusion parallels the increase of intracellular calcium

To investigate how the granule behavior is related to Ca2+ signaling, we used real-time imaging to simultaneously monitor the intracellular changes in Ca2+ fluorescence (using Oregon Green-conjugated BAPTA1 as a calcium indicator) and the distribution pattern of an α granule marker (Alexa Fluor 647 [AF-647] –conjugated fibrinogen) in unstirred platelets stimulated with 0.1 or 1 U/mL thrombin (Figure 3). The uptake of AF-647-fibrinogen was verified by determining its intracellular distribution using a gold-labeled antibody directed against AF-647 and immuno-EM (IEM) analyses. Fibrinogen was mainly detected in α granules (supplemental Figure 4A). During stimulation with 0.1 U/mL thrombin, the fibrinogen-positive spots seemed to remain similar in size to those observed in unstimulated platelets, indicating that the granules remained single. Upon stimulation with 1 U/mL thrombin, large fluorescent patches compatible with α granule fusion were observed. The intracellular Ca2+ fluorescence signals in platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin were much stronger than those in weakly stimulated cells, which displayed oscillatory Ca2+ increases (Figure 3B). Chelation of calcium with BAPTA-AM (70 µm) reduced the time-dependent formation of large fibrinogen-positive spots in platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin (supplemental Figure 4B). These observations show that granule-to-granule fusion requires high calcium signaling.

Compound fusion of fibrinogen-labeled α granules is induced by 1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were co-labeled with Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (orange, upper panel) and Alexa 647-conjugated fibrinogen (Fbg-647; red, middle panel). Platelets were washed before stimulation with thrombin (0.1 or 1 U/mL), and platelets were monitored in real time by fluorescence microscopy and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (morphology, lower panel). (A) Representative live images were recorded before stimulation (unstimulated: R) and after stimulation at the indicated times (inset). The platelets were not stirred. Arrows indicate fibrinogen-positive spots that increased in size. Single platelets are surrounded by dotted circles. Scale bar, 2 µm. (B) Representative tracings of the time course of the changes in Oregon Green BAPTA-1 staining in platelets stimulated with 0.1 and 1 U/mL thrombin. The fluorescence is expressed as the normalized fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Compound fusion of fibrinogen-labeled α granules is induced by 1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were co-labeled with Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (orange, upper panel) and Alexa 647-conjugated fibrinogen (Fbg-647; red, middle panel). Platelets were washed before stimulation with thrombin (0.1 or 1 U/mL), and platelets were monitored in real time by fluorescence microscopy and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy (morphology, lower panel). (A) Representative live images were recorded before stimulation (unstimulated: R) and after stimulation at the indicated times (inset). The platelets were not stirred. Arrows indicate fibrinogen-positive spots that increased in size. Single platelets are surrounded by dotted circles. Scale bar, 2 µm. (B) Representative tracings of the time course of the changes in Oregon Green BAPTA-1 staining in platelets stimulated with 0.1 and 1 U/mL thrombin. The fluorescence is expressed as the normalized fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Multigranular compartments result from the homotypic fusion of α granules

To explore the formation of the multigranular compartments, we examined platelets stimulated with thrombin (1 U/mL; 10 seconds) by TEM. These large compartments were swollen and contained a decondensed matrix with electron-dense material: the so-called nucleoids similar to those observed in α granules (arrows in Figure 4A-B). By using IEM, we found abundant labeling of fibrinogen and VWF, whereas serotonin staining was not detected (Figure 4C-D; supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that these structures resulted from the homotypic fusion of α granules. To determine whether the granules fused with each other before or after fusion with the plasma membrane, we incubated fixed platelets with tannic acid. Most of the large compartments displayed an electron-dense coating, but we occasionally observed unstained compartments, suggesting that granule-to-granule fusion could occur intracellularly before attachment to the plasma membrane (Figure 4E-F). FIB-SEM observations confirmed the absence of connections to the cell surface (Figure 4F-H) and revealed that these events were rare, being observed in only 4% of the platelets. Of note, the content of these granules seemed diluted, suggesting an influx of water through water channels35 or the presence of undetected thin surface-connected tethers (see “Methods”).

Multigranular compartments result from the homotypic fusion of α granules. (A-B) Ultrastructural TEM analysis of multigranular compartments in platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. Two representative TEM images illustrate the presence of nucleoids (arrows) in the aggregates. (C-D) IEM characterization of the multigranular compartments. Electron micrographs of ultrathin cryosections of platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin. Antibodies were detected with protein A coupled to 10-nm gold particles. (C) Multigranular compartments (*) were identified as fused α granules by immunolabeling with an antifibrinogen antibody. Labeling with antiserotonin was absent from these structures (*), whereas δ granules (δ) were positive. (E-F) Representative TEM images showing that the limiting membrane of the multigranular compartments (*) is not electron-dense (white arrowheads) whereas the plasma membrane is positive for tannic acid (black arrowheads). Note the presence of a δ granule close to the multigranular compartment in (E) without any fusing profile. (G-H) FIB-SEM analysis of the unstained multigranular compartments in platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. An example of the FIB-SEM raw observations and the corresponding 3D reconstruction of stained granules (in red) and an unstained multigranular compartment (in yellow) are shown. Scale bars, 500 nm.

Multigranular compartments result from the homotypic fusion of α granules. (A-B) Ultrastructural TEM analysis of multigranular compartments in platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. Two representative TEM images illustrate the presence of nucleoids (arrows) in the aggregates. (C-D) IEM characterization of the multigranular compartments. Electron micrographs of ultrathin cryosections of platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin. Antibodies were detected with protein A coupled to 10-nm gold particles. (C) Multigranular compartments (*) were identified as fused α granules by immunolabeling with an antifibrinogen antibody. Labeling with antiserotonin was absent from these structures (*), whereas δ granules (δ) were positive. (E-F) Representative TEM images showing that the limiting membrane of the multigranular compartments (*) is not electron-dense (white arrowheads) whereas the plasma membrane is positive for tannic acid (black arrowheads). Note the presence of a δ granule close to the multigranular compartment in (E) without any fusing profile. (G-H) FIB-SEM analysis of the unstained multigranular compartments in platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. An example of the FIB-SEM raw observations and the corresponding 3D reconstruction of stained granules (in red) and an unstained multigranular compartment (in yellow) are shown. Scale bars, 500 nm.

VAMP8 is a key regulator of platelet exocytosis

Previous studies demonstrated that VAMP8 regulates granule-to-granule fusion in pancreatic acinar cells36 and acts as the primary vesicle membrane SNARE (v-SNARE) in platelet granule secretion.19 To investigate its role in compound exocytosis in platelets, we first examined its subcellular distribution (Figure 5A).37 VAMP8 labeling was mostly associated with α granules in unstimulated platelets and with the multigranular compartments in 0.1 U/mL thrombin-stimulated platelets (Figure 5Ai-ii). VAMP8 was also detected on δ granules (insert in Figure 5Ai). Quantitative evaluation of gold labeling distribution in stimulated platelets confirmed that VAMP8 preferentially accumulated on the multigranular compartments in stimulated platelets (8 ± 0.6 gold particles on multigranular compartments and 2.1 ± 0.4 gold particles on α granules).

VAMP8 mediates compound exocytosis in stimulated platelets. (A) VAMP8 immunogold staining. (i) Unstimulated platelets or (ii) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 15 seconds were fixed for IEM and stained with an anti-VAMP8 antibody (detected with 10-nm gold particles). VAMP8 labeling was mostly associated with α granules in unstimulated platelets and with large multigranular compartments in thrombin-stimulated cells. The insert in (i) illustrates double immunogold labeling (VAMP810 and P-selectin [Psel]15 ). P-selectin is present in the δ granule membrane,37 and labeling allows the identification of δ granules. This image shows that VAMP8 was also present on δ granules. Scale bars, 200 nm. (B-D) FIB-SEM analysis of VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were fixed at half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). (B) Representative 2D images from FIB-SEM slices and 3D reconstructions of WT and VAMP8−/− platelets showing that granule-to-granule fusion (*) occurred in WT but not in VAMP8−/− platelets. Scale bars in the first column, 2 nm; scale bars in the second column, 500 nm. (C) Incubation with tannic acid revealed the presence of single-stained granules in stimulated VAMP8−/− platelets and multigranular compartments in WT platelets, visible on a 3D reconstruction (red) and 2D images from FIB-SEM slices (arrow in insert). α granules (yellow), δ granules (black), mitochondria (blue). (D) Left panel: 3D quantification of the exocytosis events (ie, no granular fusion [first bar], single granular fusion [second bar], and granule-to-granule fusion [third bar]) in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin (>61 and <96 platelets). Right panel: 3D quantification of the number of organelles per whole platelet in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) stimulated platelets (n = 12). Note the difference in the y-axis mean ± standard error of the mean (*, P < .05). Vertical bar of the right figure: organelles/platelet. (E-F) FIB-SEM analysis of VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated by 1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were fixed at half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). (E) Representative 2D images from FIB-SEM slices and 3D reconstructions of WT and VAMP8−/− platelets. The difference in compound exocytosis was less visible when platelets were stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin. Scale bars in the first column, 2 nm; scale bars in the second column, 500 nm. (F) 3D quantification of (left panel) the exocytosis events and (right panel) the number of organelles per whole platelets in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) -stimulated platelets (n = 12). Vertical bar of the right figure: organelles/platelet. Multigr., multigranular.

VAMP8 mediates compound exocytosis in stimulated platelets. (A) VAMP8 immunogold staining. (i) Unstimulated platelets or (ii) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 15 seconds were fixed for IEM and stained with an anti-VAMP8 antibody (detected with 10-nm gold particles). VAMP8 labeling was mostly associated with α granules in unstimulated platelets and with large multigranular compartments in thrombin-stimulated cells. The insert in (i) illustrates double immunogold labeling (VAMP810 and P-selectin [Psel]15 ). P-selectin is present in the δ granule membrane,37 and labeling allows the identification of δ granules. This image shows that VAMP8 was also present on δ granules. Scale bars, 200 nm. (B-D) FIB-SEM analysis of VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were fixed at half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). (B) Representative 2D images from FIB-SEM slices and 3D reconstructions of WT and VAMP8−/− platelets showing that granule-to-granule fusion (*) occurred in WT but not in VAMP8−/− platelets. Scale bars in the first column, 2 nm; scale bars in the second column, 500 nm. (C) Incubation with tannic acid revealed the presence of single-stained granules in stimulated VAMP8−/− platelets and multigranular compartments in WT platelets, visible on a 3D reconstruction (red) and 2D images from FIB-SEM slices (arrow in insert). α granules (yellow), δ granules (black), mitochondria (blue). (D) Left panel: 3D quantification of the exocytosis events (ie, no granular fusion [first bar], single granular fusion [second bar], and granule-to-granule fusion [third bar]) in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin (>61 and <96 platelets). Right panel: 3D quantification of the number of organelles per whole platelet in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) stimulated platelets (n = 12). Note the difference in the y-axis mean ± standard error of the mean (*, P < .05). Vertical bar of the right figure: organelles/platelet. (E-F) FIB-SEM analysis of VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated by 1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were fixed at half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). (E) Representative 2D images from FIB-SEM slices and 3D reconstructions of WT and VAMP8−/− platelets. The difference in compound exocytosis was less visible when platelets were stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin. Scale bars in the first column, 2 nm; scale bars in the second column, 500 nm. (F) 3D quantification of (left panel) the exocytosis events and (right panel) the number of organelles per whole platelets in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) -stimulated platelets (n = 12). Vertical bar of the right figure: organelles/platelet. Multigr., multigranular.

To evaluate the importance of VAMP8 in platelet exocytosis, we used platelets from VAMP8 knockout (VAMP8−/−) mice. Contrary to wild-type (WT) platelets, VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin (70 seconds) did not display multigranular compartments, indicating defective compound fusion (Figure 5B). To identify the granules connected to the extracellular space, platelets were incubated with tannic acid (Figure 5C). Individual tannic acid–positive granules were visible in 63% of VAMP8−/− platelets, whereas most WT platelets (88%) contained multigranular compartments (Figure 5D). To further characterize the role of VAMP8 in single exocytosis, we counted granules (α and δ granules), fusing granules (tannic acid positive), and multigranular compartments per whole platelet (Figure 5D). VAMP8−/− platelets contained more α and δ granules than WT platelets, suggesting that their fusion with the plasma membrane was defective and indicating that VAMP8−/− platelets had less single exocytosis. Multigranular compartments were absent in VAMP8−/− platelets. By contrast, when thrombin was increased to 1 U/mL (Figure 5E-F), WT and VAMP8−/− platelets showed similar morphology with multigranular compartments present in the cytoplasm. In addition, they contained similar numbers of granules (single and fused) and multigranular compartments. These data show that the defects resulting from lack of VAMP8 can be overridden by increasing stimulation. Altogether, these observations show that VAMP8 is a key but not a required factor for exocytosis. It plays a major role in compound exocytosis and a minor role in single-granule exocytosis, in sustained but not maximally stimulated platelets.

Compound exocytosis occurs in vivo during the formation of large thrombi

To evaluate the biological relevance of our observations, we analyzed the ultrastructure of platelet granules in thrombi formed in vivo (Figure 6). We used a laser-induced murine thrombosis model with 2 degrees of severity: a superficial vessel lesion producing a weak thrombotic response consisting of platelet adhesion without thrombin generation, and a deeper lesion resulting in the formation of a large thrombus with generation of active thrombin.38 After superficial injury, adherent platelets without signs of granule-to-granule fusion (0 of 57 platelets) were seen at the sites of endothelial denudation (Figure 6Ai-ii). Although it was not possible to use tannic acid staining in vivo, we observed that individual δ granules were often docked to the plasma membrane, suggesting that they were ready to undergo fusion (Figure 6Aii, insert). After deep vascular injury, TEM revealed a heterogeneous composition of the thrombus with mostly fully degranulated platelets (arrowhead in Figure 6Bii) at the base and granule-containing platelets near the lumen, confirming a gradient of activation (Figure 6Bi-ii).38 Importantly, well-defined, large, multigranular compartments were detected in platelets located between the fully degranulated and granule-containing platelets (insert in Figure 6Bii). These features resembled those observed in platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin in vitro (Figure 6Ci-ii) and pointed to the occurrence of compound exocytosis in vivo during thrombus formation.

Compound exocytosis occurs in vivo during thrombus formation. (A) (i) TEM analysis of a murine mesenteric artery after superficial laser injury showing adherent platelets at the site of endothelial denudation. Scale bar, 5 µm. (ii) Higher magnification showing that the platelets contain individual granules but no multigranular compartments. Note the presence of δ granules (arrowheads) close to the plasma membrane (insert in ii). Scale bar, 1 µm. (B) (i) TEM analysis of a murine mesenteric artery after deep laser injury showing disruption of the vessel wall (arrows) and a gradient of activation of platelets. Scale bar, 20 µm. (ii) Higher magnification of the box illustrating the presence of fully degranulated platelets devoid of secretory organelles (arrowhead) in the deeper area and granule-containing platelets close to the lumen. Scale bar, 1 µm. Note the presence of multigranular compartments (*) in platelets located at the interface. (Insert in ii) Platelet containing a large intracellular structure (*). (C) Ultrastructure of an in vitro aggregate. Platelets were stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin and fixed at the time point corresponding to maximal aggregation (3 minutes). (i) TEM analysis revealed a heterogeneous thrombus composed of degranulated platelets (arrowheads) at the periphery and granule-containing platelets in the center. Scale bar, 1 µm. (ii) Multigranular compartments were observed in both areas (*). Scale bar, 500 nm.

Compound exocytosis occurs in vivo during thrombus formation. (A) (i) TEM analysis of a murine mesenteric artery after superficial laser injury showing adherent platelets at the site of endothelial denudation. Scale bar, 5 µm. (ii) Higher magnification showing that the platelets contain individual granules but no multigranular compartments. Note the presence of δ granules (arrowheads) close to the plasma membrane (insert in ii). Scale bar, 1 µm. (B) (i) TEM analysis of a murine mesenteric artery after deep laser injury showing disruption of the vessel wall (arrows) and a gradient of activation of platelets. Scale bar, 20 µm. (ii) Higher magnification of the box illustrating the presence of fully degranulated platelets devoid of secretory organelles (arrowhead) in the deeper area and granule-containing platelets close to the lumen. Scale bar, 1 µm. Note the presence of multigranular compartments (*) in platelets located at the interface. (Insert in ii) Platelet containing a large intracellular structure (*). (C) Ultrastructure of an in vitro aggregate. Platelets were stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin and fixed at the time point corresponding to maximal aggregation (3 minutes). (i) TEM analysis revealed a heterogeneous thrombus composed of degranulated platelets (arrowheads) at the periphery and granule-containing platelets in the center. Scale bar, 1 µm. (ii) Multigranular compartments were observed in both areas (*). Scale bar, 500 nm.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the 3D organization of the granules within stimulated platelets by using FIB-SEM. We characterized 2 modes of membrane fusion that mediate platelet granule cargo release: single granule-plasma membrane fusion and compound granule-to-granule and plasma membrane fusion (Figure 7). Both types of fusion occur during the course of platelet secretion: fusion of individual granules with the platelet surface (ie, single exocytosis) are more obvious at lower levels of stimulation and early time points, whereas granule-to-granule and plasma membrane fusion (ie, compound exocytosis) are present at higher agonist concentration and at longer times of stimulation. The release of α granules proceeded through both modes of exocytosis, whereas release of δ granules seemed to use single exocytosis exclusively. We propose that the differences between these modes of exocytosis might explain the extent (ie, moderate vs massive) of platelet secretion.

Proposed model of platelet exocytosis. Platelets release the contents of their secretory granules through two modes of exocytosis, single or compound, depending on the strength of the stimulation. The initial fusion routes occur through the OCS and thin narrow channels (blue lines) and form small pores at the platelet surface, whereas later fusion pathways involve direct interaction with the cell surface and result in the formation of large pores. In case of weak stimulation, fusion of individual α and δ granules with the plasma membrane is observed (ie, single exocytosis). After strong stimulation, VAMP8-mediated homotypic fusion of α granules (ie, compound exocytosis) takes place. Two types of compound exocytosis may occur: (1) α granules fuse with each other and then fuse with the plasma membrane or (2) a single α granule fuses first with the plasma membrane and then other granules subsequently fuse with this granule. Highly activated platelets are completely degranulated, retaining only mitochondria and the dense tubular system in their cytoplasm. DTS, the dense tubular system.

Proposed model of platelet exocytosis. Platelets release the contents of their secretory granules through two modes of exocytosis, single or compound, depending on the strength of the stimulation. The initial fusion routes occur through the OCS and thin narrow channels (blue lines) and form small pores at the platelet surface, whereas later fusion pathways involve direct interaction with the cell surface and result in the formation of large pores. In case of weak stimulation, fusion of individual α and δ granules with the plasma membrane is observed (ie, single exocytosis). After strong stimulation, VAMP8-mediated homotypic fusion of α granules (ie, compound exocytosis) takes place. Two types of compound exocytosis may occur: (1) α granules fuse with each other and then fuse with the plasma membrane or (2) a single α granule fuses first with the plasma membrane and then other granules subsequently fuse with this granule. Highly activated platelets are completely degranulated, retaining only mitochondria and the dense tubular system in their cytoplasm. DTS, the dense tubular system.

In previous TEM studies, it was suggested that the large intracellular structures originally called vacuoles, which form in stimulated platelets, could originate from either dilated parts of the OCS or through fusion of granules with one another.29 Here, using ultrastructural 3D imaging, we clearly identified these vacuoles as being the result of granule fusion. IEM analysis showed that these large compartments arose through homotypic fusion of α granules. So far, only a limited number of studies have reported the fusion of α granules in platelets, and most have not addressed the fate of δ granules, mainly because the immunofluorescence techniques used had insufficient resolving power to permit clear differentiation of the granule populations.27,28

How do these α granules fuse upon strong stimulation? Does granule-granule fusion precede connection to the plasma membrane or not? Tannic acid staining was not detected in all multigranular compartments, and 3D rendering was unable to detect any connections with the cell surface. Although we cannot entirely exclude the possibility that tannic acid staining might be too weak to be detected in these connected structures, our data suggest that homotypic fusion of α granules precedes their communication with the extracellular space. Alternatively, one can imagine a sequential process39 in which exocytosis starts with a primary single fusion event at the plasma membrane followed by additional granule-granule fusion. Thus, single and compound exocytosis are not mutually exclusive events but instead are related and occur on a continuum as a function of the strength of the stimulation.

It is also interesting to note that 2 exit routes were identified in early activated platelets: the first corresponded to the morphologically recognizable OCS and the second to the thin channels which may represent the pipes described by Pokrovskaya et al.30 By using scanning transmission electron microscopy tomography, the authors were unable to detect any fusion between the OCS and α granules. It is unclear why our results differ from their observations; perhaps it is the result of differences in platelet activation (thrombin vs handling activation). However, considering the openings at the platelet surface, both studies lead to a similar conclusion of spatially limited access routes for early release of granule proteins.

What is the significance of single vs compound exocytosis for platelet function? We found that δ granules were mainly involved in single exocytosis, whereas α granules could participate in both patterns of granule fusion, depending on the level of platelet activation. On the basis of secretion experiments (supplemental Figure 1; Kamykowski et al12 ), one may assume that the local concentrations of the molecules released during single exocytosis are much lower than those of the molecules released during compound exocytosis. Upon strong stimulation, compound exocytosis might accelerate the secretory process, permitting the release of more granule contents to support the rapid growth of a thrombus. This is consistent with our observations of stratified granule exocytosis in more severe laser injuries where thrombin is generated. Under conditions of lower activation, as might occur at a superficial lesion, platelets may be able to fine-tune their exocytosis to maintain hemostasis without unnecessary thrombus formation.

The formation of the fusion pores is required to ensure secretion of the granule content. Therefore, a central question for the regulation of exocytosis is: what is the nature of these fusion pores? Our results indicate that the size of the fusion pores differs at the platelet surface (supplemental Figure 5). Several studies, mainly in endothelial and chromaffin cells, have indicated that fusion pores can act as a filter to limit or prevent the release of different cargo molecules depending on their size.40,41 As an example, moderate stimulation of endothelial cells triggers the secretion of small molecules such as interleukin-8 while retaining larger polypeptides and proteins such as VWF.40 It is not yet known whether similar processes occur during platelet exocytosis. IEM studies reveal that gold-labeled VWF was retained within granules in early activated platelets, whereas gold-labeled fibrinogen was localized at the opening of fusion pores, suggesting the release of fibrinogen content (supplemental Figure 6). Early fusion pores measured 58 to 79 nm, whereas later pores were approximately twofold larger (mean diameter, 120-250 nm), suggesting that the initial pores are too small to allow the passage of large proteins such as VWF multimers. Of note, previous structural studies showed that human VWF multimers correspond to ellipsoids of 175 × 28 nm, and fibrinogen molecules 45 nm long and 4.5 nm thick.42,43 However, these speculations do not take into account another layer of molecular complexity, which may come from the packing/aggregation of granular proteins. Understanding the characteristics of these aggregates (ie, their solubility and size) would help us understand how their release could be controlled.

At the molecular level, we focused on the role of VAMP8 because there was evidence that this SNARE is important for platelet exocytosis. VAMP8 is the most abundant v-SNARE in platelets, and its deletion affects release from all 3 granular stores, albeit to differing extents: δ granule release is less defective than α granule or lysosome release. Interestingly, as stimulation is increased many of the defects in VAMP8−/− platelets are overridden, suggesting that other VAMPs can compensate for the loss of VAMP8. Consistently, VAMP7−/− platelets showed a defect in release that was similar to although less dramatic than that for VAMP8−/− platelets. Individual VAMP7-positive granules translocate to the periphery of spreading platelets and fuse with the plasma membrane.39,40 VAMP8-positive granules translocated to the central granulomere in these same platelets. Our data offer insights into this distribution. In our analysis, under weak levels of stimulation, VAMP8 plays a major role in compound exocytosis and a minor role in single exocytosis. Such a result correlates with the release data because one would expect the capacity of single release events to be less. Compound fusion increases the capacity of release by giving each fusion pore at the plasma membrane access to more releasable content. Compound fusion would also be more likely in the central granulomere where granules are concentrated. The extent to which VAMP7 and VAMP8 mediate single fusion with the plasma membrane is still to be determined, but our data argue that VAMP8 is the major v-SNARE that mediates compound fusion.

Although we found that VAMP8 was expressed on δ granules, we did not detect the fusion of δ granules with one another or with α granules. This could be a result of the fact that δ granules are less numerous and too dispersed for homotypic fusion. This suggests that δ granules mainly use only single fusion as their release route, which is consistent with their release kinetics. Such a hypothesis agrees with a recent report demonstrating that individual δ granules are predocked at the plasma membrane via a Munc13-4–dependent mechanism.21 Because VAMP8−/− platelets have a smaller δ granule defect, it could imply that other SNAREs (ie, VAMP7) are more important for that secretion event. Syntaxin-8 and syntaxin-11 have both been reported to be important for δ granule release; perhaps some SNARE complexes are more efficient in facilitating single vs compound membrane fusion. Future studies are required to make these distinctions.

In conclusion, it appears that platelets have at least 2 modes of exocytosis to regulate their secretion: a single mode which leads to release of the contents of individual α or δ granules and a compound mode which leads to the formation of large intracellular compartments, allowing massive α granule release. Our findings raise intriguing questions concerning the signaling molecules and secretory machinery involved in these different types of exocytosis and their apparently distinct regulation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank François Lanza, Pierre Mangin, and Catherine Léon for critical reading of the manuscript and C. Ravanat and N. Receveur for their excellent expert technical assistance. The authors also thank Juliette N. Mulvihill for reviewing the English in the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Association de Recherche et Développement en Médecine et Santé Publique and the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: A.E. conceived and designed the research, acquired the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, designed the figures, and wrote the manuscript; J.-Y.R., N.U., and F.P. acquired the transmission electron microscopy, immuno-electron microscopy, and focused ion beam-scanning electron microscopy data; S.J. and S.W.W. provided the stimulated VAMP8−/− platelets for analysis and assisted with writing the manuscript; and C.G. conceived and designed the research, wrote the manuscript, and handled funding and supervision.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian Gachet, INSERM, Unité Mixte de Recherche S949, Université de Strasbourg, Etablissement Français du Sang-Alsace (EFS-Alsace), 10 Rue Spielmann, BP 36, 67065 Strasbourg Cedex, France; e-mail: christian.gachet@efs.sante.fr.

![Figure 2. 3D organization of the granules in stimulated platelets. To study exocytosis, platelets were stimulated with ADP (5 µM) or thrombin (0.1 or 1 U/mL), fixed at time points corresponding to (A) shape change or (B) half-maximal aggregation, stained with tannic acid, and prepared for FIB-SEM. Tannic acid coats the cell surface, fills the OCS, and enters the granules undergoing secretion. Two images from FIB-SEM slices of stimulated platelets (right, detail of the granules) and a 3D reconstruction of stained granules (in red) and unstained granules (in yellow) are shown for each condition. Scale bars in the first column, 500 nm; scale bars in the second column, 200 nm. Images are representative of at least 3 different experiments. (A) Maximal platelet shape change. (i-iii) Platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 7 seconds). Note that single granules and OCS remained in separate compartments. (iv-vi) Platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 15 seconds. Some single granules are tannic acid–positive. (vii-ix) Platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 10 seconds. (*) Indicates stained aggregates of granules. Note that the connections with the platelet surface pass through narrow OCS channels (arrows), resulting in small pores at the cell surface. (B) Half-maximal aggregation. (i-iii) In platelets stimulated with ADP (5 µM; 30 seconds), the granules remained unstained. (iv-vi) In platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 70 seconds, 2 pools of granules are visible. (vii-ix) In platelets stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin for 70 seconds, the fused granules form large intracellular compartments (*) which are all in contact with the external space, creating large fusion pores at the platelet surface (arrows). Bar graphs represent the quantification of the exocytosis events (ie, no granular fusion [white bar], single granular fusion [gray bar], or granule-to-granule fusion [black bar], in response to different degrees of platelet stimulation and different time courses of activation). Three experiments were performed for each condition with >150 platelets in each case. Vertical bars indicate mean ± standard error of the mean. (C) Representative SEM images of (i) unstimulated platelets, (ii) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin and fixed at time points corresponding to shape change (15 seconds), and (iii) half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). The fusion pores are indicated with black arrows, and OCS openings are indicated with a white arrow. Scale bars, 1 µm. (D) Time course of α granule cargo release from platelets stimulated with 0.1 and 1 U/mL thrombin. At the indicated times (in seconds), thrombin stimulation was stopped with hirudin (100 U/mL), and platelets were immediately centrifuged at 16 000g for 5 minutes. The releasates were assayed for PF4 content (square), fibronectin content (triangle), and VWF activity (circle) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Each time point corresponded to 3 separate experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/128/21/10.1182_blood-2016-03-705681/4/m_blood705681f2.jpeg?Expires=1767806953&Signature=Lc4bA0ijo7Y1AlYfGi1zbcbnYM6zqmMC9qGK3aiyX4JCjrWsFbrxmAcWS-ZAMcr38IQ3woVD1Q1kEY6en92QF8n2pbiZlyFfA1u7fHQw4HjdNusXf2FQfBcjoCysVcJZJUK9PHeAOBuRVSSYGe4bUfSdpZokuMAq26ZBf1x-lT~vRXUftQJ1gKYCbOl~1na4Tz2-Gc4fnWEhO9TNDjljP6vHravJx8X7-DvH~w4CP8ri6SO5BMr236SxjBTsH1NTen88uojlJdGKan7~1pcAqxbN-J2fBZ13i~ad104VTNcLhsU6gb6EQy9E6QBFHUTU3-PH2dHJT2Ar~jX2oRsLdA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. VAMP8 mediates compound exocytosis in stimulated platelets. (A) VAMP8 immunogold staining. (i) Unstimulated platelets or (ii) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin for 15 seconds were fixed for IEM and stained with an anti-VAMP8 antibody (detected with 10-nm gold particles). VAMP8 labeling was mostly associated with α granules in unstimulated platelets and with large multigranular compartments in thrombin-stimulated cells. The insert in (i) illustrates double immunogold labeling (VAMP810 and P-selectin [Psel]15). P-selectin is present in the δ granule membrane,37 and labeling allows the identification of δ granules. This image shows that VAMP8 was also present on δ granules. Scale bars, 200 nm. (B-D) FIB-SEM analysis of VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated by 0.1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were fixed at half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). (B) Representative 2D images from FIB-SEM slices and 3D reconstructions of WT and VAMP8−/− platelets showing that granule-to-granule fusion (*) occurred in WT but not in VAMP8−/− platelets. Scale bars in the first column, 2 nm; scale bars in the second column, 500 nm. (C) Incubation with tannic acid revealed the presence of single-stained granules in stimulated VAMP8−/− platelets and multigranular compartments in WT platelets, visible on a 3D reconstruction (red) and 2D images from FIB-SEM slices (arrow in insert). α granules (yellow), δ granules (black), mitochondria (blue). (D) Left panel: 3D quantification of the exocytosis events (ie, no granular fusion [first bar], single granular fusion [second bar], and granule-to-granule fusion [third bar]) in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) platelets stimulated with 0.1 U/mL thrombin (>61 and <96 platelets). Right panel: 3D quantification of the number of organelles per whole platelet in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) stimulated platelets (n = 12). Note the difference in the y-axis mean ± standard error of the mean (*, P < .05). Vertical bar of the right figure: organelles/platelet. (E-F) FIB-SEM analysis of VAMP8−/− platelets stimulated by 1 U/mL thrombin. Platelets were fixed at half-maximal aggregation (70 seconds). (E) Representative 2D images from FIB-SEM slices and 3D reconstructions of WT and VAMP8−/− platelets. The difference in compound exocytosis was less visible when platelets were stimulated with 1 U/mL thrombin. Scale bars in the first column, 2 nm; scale bars in the second column, 500 nm. (F) 3D quantification of (left panel) the exocytosis events and (right panel) the number of organelles per whole platelets in WT (gray) and VAMP8−/− (blue) -stimulated platelets (n = 12). Vertical bar of the right figure: organelles/platelet. Multigr., multigranular.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/128/21/10.1182_blood-2016-03-705681/4/m_blood705681f5.jpeg?Expires=1767806953&Signature=099DztJbiKARZUDQw8ZjO9oP30HDUXg2B0ZNZohBe3dLj6cVCp-Vj1hlUoIUx2SzD9mHXAX14VHof8nvHeZqsBDA4zOVGcTceBzXwT8Xu8IquFcLlr0Y2mr8NoLzZROW1VHCxIN~nTyx63V7klmiQn-YPfqUAWMxNZxenoaARLA9rT130vL3AyVxo-O8tcRMpkEDs~AtlyzoqT4quwKsLzXYQBJkglJvAPQwYO1nsYlMwo5QvLwwOn4o5gYUGnVsIwLGfULgEstFDtp3KNq-IVq-XX7aSM4iSNR3yWBgVOYEH97NOQlS-mtFRbYAfzJUsXOQuBkbgQUuv2-Q6kZ4kw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal