Abstract

Background

Bone marrow (BM) microenvironment is involved in the initiation and propagation of normal hematopoiesis as well as hematological diseases. Leukemia and high dose chemotherapy affect both hematopoietic and stromal precursor cells. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MMSCs) are the essential element of both healthy and leukemic hematopoietic microenvironment.

Aims

To investigate two types of stromal precursor cells, MMSCs and their more differentiated progeny CFU-Fs, derived from the BM of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients before and after therapy.

Methods

74 newly diagnosed cases (33 AML, 21 ALL, 20 CML) were involved in the study after informed consent. BM was aspirated prior to any treatment (time-point 0) and at days 37, 100 and 180 since the beginning of treatment of acute leukemia (AL) and +3, +6 and +12 months for CML (time-points 1-3). MMSCs were cultured in aMEM with 10% fetal calf serum. Time to P0 and cumulative MMSC production after 3 passages were evaluated. CFU-F concentration was analyzed in standard conditions.

Results

At the time of the diagnosis the percentage of blast cells in the bone marrow of patients with AML was 22-86,6% (median 64%). After the induction therapy complete remission (CR) was achieved in 58% of patients. Patients who didn't achieve CR were switched to the alternative chemotherapy regimens. The percentage of blast cells in the bone marrow of patients with ALL at the diagnosis was 68-97% (median 88%). After the induction therapy complete remission (CR) was achieved in 90% of patients.

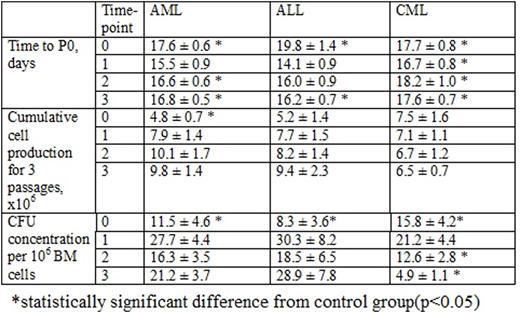

Time needed to reach P0 reflects the quantity of MMSC in the BM sample. The time to P0 in control group was 13.7 ± 0.3 days. The elongation of time to P0 in AL MMSC cultures at the time of the diagnosis (Table 1) suggested the reduction of MMSC number or their decreased proliferative potential due to leukemic expansion. After the induction therapy time to P0 reached the normal level, but subsequently lengthened during the consolidation therapy and before the maintenance therapy, that can be explained by the chemotherapy influence. In CML MMSC cultures time to P0 was also significantly longer during the whole observation period due to the continuous therapy and maintaining disease.

Cumulative MMSC production in control group was 7.1 ± 1 x 106 cells. In patients with AML it was 1/3 of the donor's at the time of the diagnosis with no difference at time-points 1, 2 and 3, indicating the impaired proliferative abilities of MMSC at the AML manifestation due to the disease aggressiveness or the patient's elder age. Cumulative MMSC production in patients with ALL and CML didn't differ from donor's. BM blast count did not correlate with MMSC production. Among patients with AL, who didn't achieve CR, the time to P0 and total MMSC production did not differ significantly from that of the patients in remission.

CFU-F concentration in the BM of AL patients was significantly lower (almost halved) than in donors (25.4 ± 3.1 per 106 BM cells) at the time-point 0 with no difference at time-points 1, 2 and 3. CFU-F concentration in the BM of CML patients was also nearly 40% lower than in control group at the time-point 0 with its following restoration at time-point 1 and subsequent drop at next time-points (up to 5 fold lower) at time-point 3) (Table 1), reflecting the long-lasting lesion of these group of precursors during the course of the disease. There were no correlations between BM blast count and CFU-F concentration in all nosologies studied.

Conclusion

The study supports the major influence of leukemic cells and chemotherapy on the BM microenvironment. The two types of studied precursors are affected differently. Future studies are needed to evaluate the role of MMSCs in leukemia pathogenesis.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal