Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

New immigrant families from continental Africa account for an increasing proportion of pediatric patients with Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) in Canada and North America. As families enter the western medical system they face a myriad of tests and medications as well they encounter language barriers, endless forms and large teams. Previous experiences with healthcare also influence families' expectations and adjustment.There is no published data exploring the experiences of these families to help guide practice. Resources such as the Canadian Pediatric Society guide on immigrant health are not specific to SCD. We set out to examine cultural sensitivity methodologically in order to improve delivery of care.

Research Questions:

What are newcomer families' experiences with SCD in Canada and their home country?

What are the prevailing values and beliefs related to SCD that shape the attitude and behaviors of newcomer families?

How do newcomer families perceivethe current delivery of medical care (the barriers and the facilitators)?

METHODS:

Focused ethnography was used to understand the socio-cultural context in which newcomer families from Africa experience their child's SCD; to explore their perspectives, beliefs, how they manage daily life and experience the western medical system. A sample size of12-15 participants was selected to reach saturation.Participants were selected using purposeful and convenience sampling and semi-structured interviews were held with the primary caregiver(s) with use of aninterpreter if needed. Research Ethics Board approved.

RESULTS:

Saturation was reached at 10 families and 12 were interviewed due to recruiting methods.

Demographics:12 caregivers (N=8 females; N=4 males); most were in their forties and from Congo, Nigeria or Liberia. The majority had 3 or more children, were married and employed. The majority did not have extended family within the region. Languages spoken at home were English, French, Yoruba, Swahili orMoorie. They immigrated to Canada between 2002 and 2015

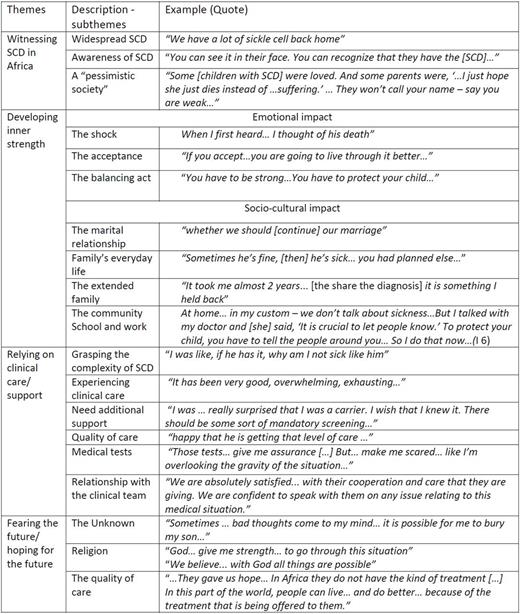

For themes see table 1.

CONCLUSIONS:

Participants' attitude, perception and knowledge about SCD were profoundly affected by their experiences in their countries of origin. These mostly negative experiences (seeing children suffering without appropriate medical care; observing social stigma, etc.) were deeply embedded and determined their response to SCD in their children.

1. Practice guideline: Allow for sufficient time and provision oftranslation services to explore the families' experience with stigma within country of residence and origin as well as embedded in the healthcare system and the community.

Despite the prevalence of SCD in their home countries the diagnosis was a surprise. The path towards acceptance was slow, emotionally convoluted and not linear. Acceptance of the diagnosis is a process and devastating in the context of previous experiences.

2. Practice guideline: Review diagnostic information early and have easily accessible information about SCD available for parents/family network. This information will also need to be reviewed with the child at key developmental time periods.

SCD has a dominant impact on life causing renegotiation of all relationships: spousal, family, community, co-workers and school staff. Managing SCD influenced daily routines imposing structure which was disrupted for hospitalizations. Families were reluctant to leave children unattended in the hospital and thus sacrificed personal and employment goals. Social support is limited and families cope alone.Families tend to seek practical support and deny the desire for emotional support.

3. Practice guideline: 3a)Screen for potential isolation and explore whether other caretakers are aware of diagnosis and disease specific care 3b) Given the tendency to deny emotional support needs, lack of nearby extended family and the stigma in the community setting up networks that provide both practical and instrumental support could be meaningful and more likely utilized resources.

The life-long complexity of SCD creates anxiety for the child's life expectancy. Families trust in medical expertise, improvements in medical treatments and their faith/religious beliefs are foundations for hope.

4. Practice guideline: HCP working with families should ensure awareness of clinical advances and develop means to easily share knowledge as it will strengthen hope for the future.

Bruce:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria; Apopharma: Consultancy.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal