Abstract

Background

The use of 5-azacytidine (AZA) as front line therapy in elderly, frail patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) has entered in clinical practice. Our retrospective therapeutic experience with AZA in 52 AML patients is presented and compared with intensive chemotherapy (FLAI-GO).

Materials and methods

We retrospectively analysed the outcome of 52 elderly AML patients treated with AZA as front line therapy from June 2010 to June 2016. We compared the outcome with that of a cohort of a 55 partially matched AML patients who had received FLAI-GO from September 2004 to January 2010.

The two populations were comparable for sex, karyotype, FLT3 mutational status, LDH levels, WT1 and BAALC expression levels. The two cohorts significantly differed for median age (76.5 and 71 years for AZA and FLAI go, respectively), percentage of patients older than 70 years (77% vs 58%), secondary disease (75% vs 31%), mean leukocytes count (8850/mmc vs 2800/mmc ). Relevant comorbidities were present in both arms. AZA was administrated monthly (75 mg/mq5+2 schedule) until disease progression or toxicity (mean 7 courses range 1-27). FLAI-GO consisted inFludarabine30 mg/mq,Cytarabine1000 mg/mq,Idarubicin5 mg/mq(day 1-2-3) andGemtuzumabozogamicin(3 mg /mq) on day 4. Those achieving CR after induction received an identical consolidation cycle, those not in CR were treated with salvage therapy (MEC, MEA, MINI ICE or low dose chemotherapy).

Results

Early death rate was comparable between the two arms (5/52 for AZA 3/55 for FLAI-GO). CR rate was lower in patients treated with AZA (12,8 %) compared with those receiving FLAI-GO (52%). No factors influenced theprobability of achieving CR in AZA arm (sex, disease onset, karyotype, WBC count, age, blasts, LDH, WT1 and BAALC levels) although none of the 3 patients with FLT3-ITD mutation showed any kind of response. In FLAI-GO arm the only factor which impacted on response rate was sex (CR rate was 69.2% and 34.6% in women and male, respectively, p=0,025). We observed a lower probability of CR in patients with higher bone marrow blast burden (CR rate of 80% with blasts <30% vs 45.5% with blasts > 30%) and in patients with elevated BAALC (75% CR with BAALC <1000 and 38.5% with BAALC > 1000).

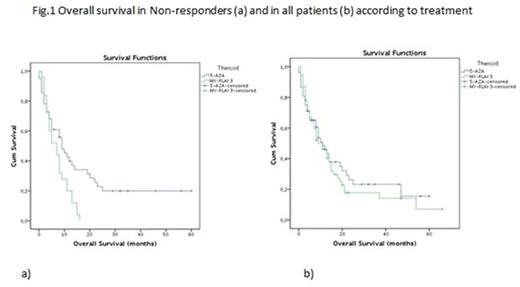

The 1 and 2 years OS were 46 and 21 % in all patients (median 11 months),with no differences in AZA (45,9% and 26,2% ) and FLAI-GO arm ( 46,3% and 17,8%). In AZA group karyotype, FLT3 mutational status, WT1 expression significantly impacted on OS. In multivariate analysis only FLT3-ITD mutation retained its prognostic impact on OS (p = 0.02) .

Achieving CR after AZA induction did not deeply modify OS probability, as there was no significant difference between patients in CR or not after AZA (even with a trend in favour of patients with CR). Non responders (NR) had a 1 year OS of 40% (median 9 months); patients with CR had a 1 year OS of 83.3% (median 47 months). Patients with an haematological improvement (HI) had a 1 year OS of 48% .

In FLAI-GO arm the variables significantly influencing OS were: type of response (NR patients had a 2 years OS of 0% whereas CR patients had a 2 yeas OS of 38%), sex, WBC; neither karyotype, expression of BAALC , disease status, FLT3-ITD, WT1 expression, NPM1 mutation, blasts , age over 70 or LDH had a prognostic impact on OS. In multivariate analysis the only factor which impacted the survival was the achievement of CR to induction chemotherapy (p=0,000).

Infection rate was 28/52 in AZA arm and 40/55 in FLAI-GO arm. The hospitalization rate was significantly lower in AZA arm compared to FLAI-GO (8.5 days vs 27 days in the first 30 days; 11.3 vs 51 in the first 90 days; 15 vs 64.5 in the first 180 days).

Conclusions

In our study AZA has shown to be well tolerated in a group of elderly frail patients until recently eligible only for best supportive care or low dose chemotherapy. AZA is less effective than FLAI-GO in inducing CR in all subgroups of patients but this doesn't translate into a lower OS. In the AZA arm the achievement of CR (or PR) is not fundamental for the duration of survival, unlike what has been observed in the FLAI-GO treated cohort. Our study suggests that some subgroups of patients may benefit more from AZA and others more from aggressive approaches; patients with low BAALC levels and with FLT3 mutation seem to benefit from FLAI-GO. Larger prospective trials evaluating clinical, cytogenetic and molecular risk factors in patients receiving AZA or chemotherapy will help to tailor the best therapy for each patient.

Gobbi:Novartis: Consultancy, Research Funding; Gilead: Honoraria; Celgene: Consultancy; Mundipharma: Consultancy, Research Funding; Janssen: Consultancy, Honoraria; Takeda: Consultancy; Roche: Honoraria.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal