Key Points

Angiogenesis preceded infiltration of inflammatory leukocytes during GVHD as well as during experimental colitis.

Metabolic alterations and cytoskeleton changes occurred during early angiogenesis, but classical endothelial activation signs were absent.

Abstract

The inhibition of inflammation-associated angiogenesis ameliorates inflammatory diseases by reducing the recruitment of tissue-infiltrating leukocytes. However, it is not known if angiogenesis has an active role during the initiation of inflammation or if it is merely a secondary effect occurring in response to stimuli by tissue-infiltrating leukocytes. Here, we show that angiogenesis precedes leukocyte infiltration in experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease and acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). We found that angiogenesis occurred as early as day+2 after allogeneic transplantation mainly in GVHD typical target organs skin, liver, and intestines, whereas no angiogenic changes appeared due to conditioning or syngeneic transplantation. The initiation phase of angiogenesis was not associated with classical endothelial cell (EC) activation signs, such as Vegfa/VEGFR1+2 upregulation or increased adhesion molecule expression. During early GVHD at day+2, we found significant metabolic and cytoskeleton changes in target organ ECs in gene array and proteomic analyses. These modifications have significant functional consequences as indicated by profoundly higher deformation in real-time deformability cytometry. Our results demonstrate that metabolic changes trigger alterations in cell mechanics, leading to enhanced migratory and proliferative potential of ECs during the initiation of inflammation. Our study adds evidence to the hypothesis that angiogenesis is involved in the initiation of tissue inflammation during GVHD.

Introduction

The number of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations (bone marrow transplantations, allo-BMT) performed worldwide is increasing, as it often is the only curative treatment of hematologic malignancies. Despite the maximum use of therapeutic options, many patients die of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a systemic inflammatory disease primarily attacking liver, skin, and intestines, implicating a large unmet medical need for the development of novel therapies. There is increasing evidence demonstrating that the vascular endothelium can be used as a therapeutic target during GVHD.1,2 In preclinical models as well as in patients, it has been demonstrated that GVHD is associated with the formation of new blood vessels.2-5

Under pathological conditions,6-10 such as increased secretion of proangiogenic mediators by inflammatory cells, tissue damage, or oxygen and nutrient deficiency, endothelial cells (ECs) can rapidly form new blood vessels in a tightly orchestrated process. It involves the activation of ECs, the degradation of the extracellular matrix, the vessel sprouting relying on migratory, guiding “tip” cells and elongating, proliferative “stalk” cells, morphogenesis, and the vessel stabilization by recruitment of pericytes. More recently, metabolic processes in ECs11-13 involving fatty acid oxidation (FAO)14,15 and glycolysis16,17 have been shown to be important for initial steps of angiogenesis. Many of these processes can modulate angiogenic as well as inflammatory regulatory mechanisms and activating or targeting one can induce or modify the other,7,8 underlining the importance of the crosstalk between angiogenesis and inflammation. In animal models of inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and GVHD, it has been demonstrated that the inhibition of angiogenesis can be used therapeutically to reduce the recruitment of tissue-infiltrating leukocytes.4,8,18,19 However, it is not known if angiogenesis contributes to the initiation of inflammation or is a mere consequence of inflammation.20

We analyzed the role of angiogenesis during the initiation of inflammation in experimental models of IBD and GVHD, which occurs after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Materials and methods

Study design and statistics

Sample size for GVHD experiments was calculated by estimation of time point–specific analyses based on the Student t test assuming 80% power and 0.05 2-sided level of significance. Experiments with at least 5 animals per group (untreated [naïve], conditioned-only [chemo], allogeneic [ALLO], or syngeneic [SYN] transplanted mice) were performed 2 times.

Specific time points for analyses were chosen after initial time course experiment. All collected data were used in statistical analyses, only excluding animals that died before specific time points for data collection. Animals were randomized, including equal distribution of weight status and mixed housing of different transplanted animals. For subsequent analyses, transplant conditions were encoded. All experiments were approved by the Regional Ethics Committee for Animal Research (State Office of Health and Social Affairs, Berlin).

Survival data were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. For all other data, the Student unpaired t test (2-tailed) was used if not indicated differently. Normality tests and F test confirmed Gaussian distribution and equality of variance between different groups. Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Values of P ≤ .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA).

Mice

Female C57BL/6 (B6) (H2b), 129S2/SvPasCrl (129) (H2b), LP/J (H2b), B6D2F1 (BDF) (H2b/d), BALB/c (H2d), B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-DsRed*MST)1Nagy/J (DsRed+B6) (H2b) mice (10–12 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany) and housed in the Charité University Hospital Animal Facility. Mice were individually scored twice a week for 5 clinical parameters (posture, activity, fur, skin, and weight loss) on a scale from 0 to 2. Clinical GVHD score was assessed by summation of these parameters. Survival was monitored daily.

GVHD experiments

For GVHD models LP/J→B6, B6→BDF, 129S2/Sv→B6, DsRed+B6→BDF, recipient mice received intraperitoneal doses of 20 mg/kg per day busulfan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 5 days, followed by 100 mg/kg per day cyclophosphamide (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 days and were injected intravenously with 1.5 × 107 bone marrow (BM) cells and 2 × 106 splenic T cells from allogeneic and syngeneic donor mice on day 0. For B6→BALB/c, recipient mice received 900 cGy total body irradiation from a 137Cs source as a split dose with a 3-hour interval and were injected intravenously with 5 × 105 BM cells and 1 × 106 splenic T cells. BM was flushed from the tibia and femur, and single-cell suspension was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/2% fetal calf serum/1 mm EDTA by gently passing through a 23-G needle and over a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Splenic T-cell suspension was obtained using the Pan T-cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) inhibition, LP/J→B6, B6 mice were treated intraperitoneally 2 times a week with 5 mg/kg B20-4.1.1 (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) or 5 mg/kg rat immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2; Sigma-Aldrich). For VEGFR1/2 inhibition, B6→BALB/c, BALB/c mice were treated intraperitoneally on days 0, +2, +4, +8, +10 with a combination of 800 μg DC101 and MF1 (ImClone Systems, New York, NY) or with 800 μg rat IgG2.

Colitis (IBD) experiments

For colitis induction, 3% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) was administered to B6 mice in drinking water. For DsRed colitis experiments, B6 mice received 1.5 × 107 BM cells from DsRed+B6; at day+40 after BMT, DsRed+BM chimeras with >90% DsRed+ cells in blood were used for DSS induction. For endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) experiments, B6 mice received on the day of DSS induction intravenously 5 × 104 DsRed+EPCs, which were fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) (CD11b−, Ter119−, c-Kit+, VEGFR2+) from DsRed+B6 BM using a Bio-Rad S3 Cell Sorter. Purity was 90% or higher.

Immune fluorescence staining

Tissue samples were cryoembedded in Tissue-Tek (Sakura Finetek, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands). Sections measuring 7 μm were acetone fixed (−20°C), blocked with PBS/3% bovine serum albumin /5% fetal calf serum, and stained overnight at 4°C with primary rat monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against CD4 (H129.19, 1:500), CD8 (53-6.7, 1:500), CD11b (M1/70, 1:200), Gr1/Ly-6G (RB6-8C5, 1:200), major histocompatibility complex-I (MHC-I)/H2kb (AF6-88.5, 1:200), CD31 (MEC13.3, 1:400), panendothelial cell antigen (MECA-32, 1:500) from BD Biosciences and MHC-II (ER-TR3, 1:200) from BMA Biomedicals (Augst, Switzerland); with hamster mAb against CD31 (2H8, 1:500) and rabbit polyclonal Ab against Ki67 (PA5-19462, 1:200) from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). For visualization, 1:1000 secondary donkey anti-rat antibody Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-rabbit antibody Alexa 555 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), goat anti-hamster Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), and nuclear counterstaining with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. To determine Marker+ area, 6 sections per sample were investigated with the ×20/0.50 objective of BA410 epifluorescence microscope (Motic, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong), and pictures were acquired with Moticam Pro 285B camera and Motic Images Plus 2.0 Software from Motic. Marker+ area to total area was quantified with a predetermined threshold using Fiji Software (http://fiji.sc/Fiji). Increase in vascular density was determined by elevated percentage of positive area of the stained EC marker CD31 or MECA. For analysis of EC proliferation, 10 high-power-field photographs per sample were taken with the ×40/0.75 objective of a BA410 epifluorescence microscope. The number of Ki-67+ cells in direct contact with CD31 signal (Ki67+ ECs) per high-power field was counted. For Z-stacks, 21-μm sections were analyzed with a Zeiss LSM700 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), and 20 sections per picture were taken.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed twice and stained for 20 minutes at 4°C in PBS/0.5 mM EDTA/0.5% bovine serum albumin with the following rat mAbs from BD Biosciences: anti-CD31 (MEC13.3-APC and PE), anti-VEGFR2 (AVAS12α1-PE), anti-ICAM (3E2-PE), anti-ckit (2B8-APC), anti-CD45 (30F11-PerCP-Cy5.5 and FITC), anti-CD11b (M1/70-APC-Cy7), anti-Ter119 (Ter119-PE-Cy7), anti-H2kb (AF6-88.5-FITC). Samples were analyzed by BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo 7.6.5 Software (TreeStar Inc, Ashland, OR). In liver, ECs were determined as Ter119-CD11b-CD45dim/−CD31+ cells.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA and complementary DNA, obtained using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) and the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions, were amplified (50°C, 2 minutes; 95°C, 10 minutes; 49 cycles of 95°C, 10 seconds; 60°C, 1 minute) on DNA Engine Opticon (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Life Technologies), and Vegfa, VEGFR2, Icam1, Vcam1, P- and E-selectin primers and probe from BioTez GmbH (Berlin, Germany). Data were analyzed with Opticon Monitor 3.1 analysis software (Bio-Rad) and the comparative CT Method (ΔΔCT Method).

EC isolation

Single-cell suspensions from liver and colon were generated via digestion at 37°C and continuous shaking with 2 mg/mL Collagenase D (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) for 45 minutes and 1 mg/mL collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 minutes, respectively. Cells were passed twice over a 70-μm cell strainer. Liver ECs were additionally enriched with gradient centrifugation using 30% Histodenz (Sigma-Aldrich) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For pure EC populations, liver cells were magnetic-activated cell sorted (MACS)–isolated using CD146 liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) after manufacturer’s instructions, and colon cells were FACS-sorted (CD11b−, CD45dim/−, CD31+) using a Bio-Rad S3 cell sorter. Purity was checked via flow cytometry analysis of ICAM1 and CD31.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA from colon EC was isolated with the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies) and subjected to microarray analysis (GeneChip Mouse Gene 2.0 ST Array; Affymetrix). Obtained raw data were normalized with Expression Console Software and analyzed with Transcriptome Analysis Console Software (Affymetrix) with the following parameters: Fold Change (linear) < −2 or >2, analysis of variance P value (Condition pair) < 0.05.

LC-MS/MS proteome analysis

At day+2 after BMT, proteins from liver EC from allogeneic- and syngeneic-transplanted mice were isolated and quantified by dimethylation labeling,21,22 subjected to high through-put liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis, and MS data were processed23,24 as described in detail in the supplemental Material and methods, available on the Blood Web site. Quantitative ratios were calculated and normalized by Max Quant software package. R software (Version 3.0.0, www.r-project.org) was used to calculate log2 ratios between syn- and allo-transplanted groups, log10 of signal intensities, and P values of protein abundance changes. P values < .05 were chosen as statistically significant. Normalized ratios were used for differential expression analysis (up ≥1.3 or down ≤0.44). Protein information (names, cellular localization, involved functions, and pathways) were obtained from UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org/).

Real-time deformability cytometry

Results

Angiogenesis precedes lymphocyte infiltration in acute GVHD and in an experimental model of IBD

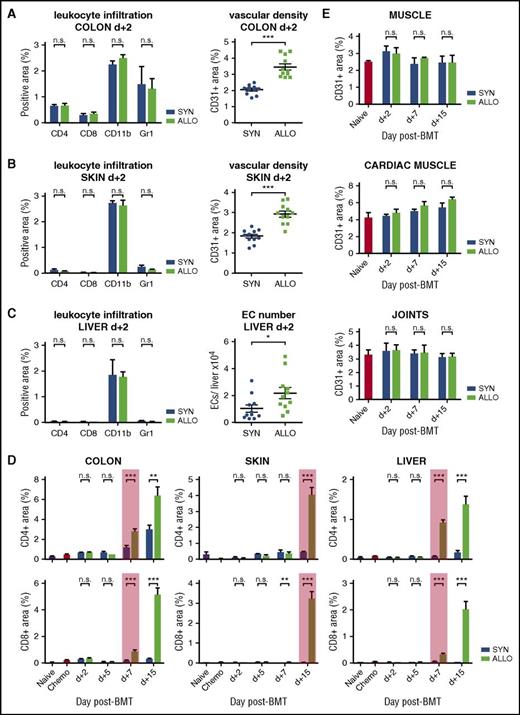

To shed light onto initial mechanisms of both processes after allo-BMT, we first determined the time course of angiogenesis (supplemental Figure 1) as well as of leukocyte infiltration in a clinically relevant murine MHC-matched, minor histocompatibility antigen–mismatched GVHD model (LP/J [H2kb] →C57BL/6 [H2kb]).27 In allo-BMT recipients, we found significant increased vascular density in the colon and skin and significantly increased EC numbers in liver already on day+2 after BMT (Figure 1A-C). In contrast, infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells into GVHD target organs did not occur until day+7 in colon and liver and until day+15 in skin (Figure 1D). Also, the pan myeloid cell marker CD11b as well as the neutrophil marker Gr-1/Ly-6G did not show significant differences in the GVHD target organs at day+2, emphasizing that monocytes/macrophages/neutrophils as well as lymphocytes did not infiltrate prior to the occurrence of angiogenesis (Figure 1A-C). Strikingly, conditioned mice and syn-BMT recipients exhibited no change in vascular density, showing that early angiogenesis was specific to GVHD and allo-BMT (supplemental Figures 1 and 2A,B). We confirmed the results with another panendothelial cell marker MECA-32 (supplemental Figure 3) and in 2 other murine GVHD models (129S2/SvPasCrl→C57BL/6 and C57BL/6→B6D2F1) (supplemental Figures 4A,B and 5). Our results demonstrate that angiogenesis is an initial event during GVHD, whereas GVHD-associated infiltration of inflammatory cells occurs secondarily.

Angiogenesis occurs exclusively in target organs and precedes leukocyte infiltration during GHVD. (A-C) Leukocyte infiltration: percentage of CD4-, CD8-, CD11b-, and Gr1-positive area in GVHD-target organs colon, skin, and liver of allogeneic (ALLO) compared with syngeneic transplanted mice (SYN) 2 days (d+2) after BMT. Vascular density: percentage of CD31-positive area in colon and skin and EC number in liver of SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT. (D) Time course of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte infiltration. The red box marks first significant increase in CD4- and CD8-positive area in ALLO mice. Untreated (Naive) and only chemotherapy-conditioned (Chemo) mice served as control and showed no infiltration. (E) Vascular density in nonclassical target organs skeletal and cardiac muscle and joints at day+2, +7, and +15 after BMT. Untreated mice (Naive) served as control. Data pooled from 2 independent experiments (naive, chemo, n = 5 per group; SYN, ALLO, n = 10-12 per group). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n.s., not significant by Student t test (2-tailed).

Angiogenesis occurs exclusively in target organs and precedes leukocyte infiltration during GHVD. (A-C) Leukocyte infiltration: percentage of CD4-, CD8-, CD11b-, and Gr1-positive area in GVHD-target organs colon, skin, and liver of allogeneic (ALLO) compared with syngeneic transplanted mice (SYN) 2 days (d+2) after BMT. Vascular density: percentage of CD31-positive area in colon and skin and EC number in liver of SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT. (D) Time course of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte infiltration. The red box marks first significant increase in CD4- and CD8-positive area in ALLO mice. Untreated (Naive) and only chemotherapy-conditioned (Chemo) mice served as control and showed no infiltration. (E) Vascular density in nonclassical target organs skeletal and cardiac muscle and joints at day+2, +7, and +15 after BMT. Untreated mice (Naive) served as control. Data pooled from 2 independent experiments (naive, chemo, n = 5 per group; SYN, ALLO, n = 10-12 per group). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n.s., not significant by Student t test (2-tailed).

We asked the question if initial angiogenesis is specific to GVHD or likewise precedes infiltration of leukocytes in other inflammatory diseases. In a standard model for IBD, the DSS-induced colitis (supplemental Figure 6A) was found to have similar results to GVHD experiments. CD31+ vascular density was significantly increased already at day+1 after colitis induction (supplemental Figure 6B-D), whereas infiltration of CD4+, CD8+, and CD11b+ cells was not significantly increased in colon until day+3 (supplemental Figure 6B,C,E-G).

GVHD non–target organs showed no angiogenesis and lymphocyte infiltration

To investigate if early angiogenesis occurs in the context of systemic inflammation or is specific to GVHD target organs, we analyzed joints, skeletal, and cardiac muscle. These organs are prone to angiogenesis under pathological conditions,6,7,28 but they are typically not affected by acute GVHD. We found no significant change in vascular density as well as no lymphocyte infiltration in the non–classical target organs of allo-BMT vs syn-BMT recipients at day+2 or any later time points (Figures 1E; supplemental Figure 7).

No early incorporation of EPCs in experimental models of GVHD and IBD

Next, we analyzed if the early increase in vascular density is dependent on the proliferation of resident tissue ECs (angiogenesis) or on the incorporation of BM-derived EPCs, termed vasculogenesis.8 We first confirmed that at day+2 after BMT, allo-BMT recipients showed increased numbers of proliferating (Ki67+) ECs in colon compared with syn-BMT recipients (Figure 2A). To determine EPC incorporation, we transplanted B6D2F1 mice with DsRed+C57BL/6 BM cells and T cells to induce GVHD. We could not detect costaining signals of DsRed and CD31 in colon and skin of allo-BMT recipients at day+2 (Figure 2B). Similarly, DsRed+ BM chimeras as well as C57BL/6 mice receiving EPCs from DsRed+C57BL/6 BM showed no significant amount of CD31+DsRed+ coexpressing cells in colon until day+4 after induction of colitis (Figure 2C,D). Our data suggest that the initial formation of blood vessels during GVHD and during experimental colitis is due to the formation of new blood vessels from existing ones, termed angiogenesis.

No early incorporation of EPCs in experimental models of GVHD and IBD. (A) Number of proliferating (Ki67+) ECs in colon of SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (n = 3 per group). White arrow marks proliferating EC (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI+] [blue], Ki67+ [red-A555] in direct contact with CD31 [green-A488] signal). White asterisks mark proliferating crypt cells. (B) Representative pictures of green-A488 CD31 (vessel-related), DsRed (BM-related), and merged signals of colon and skin sections from SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (DsRed+C57BL/6→B6D2F1). (C) Representative pictures of green-A488 CD31, DsRed, and merged signals of colon sections from DsRed+ BM chimeras at day+4 after DSS colitis induction. (D) Representative projections of Z-stacks of colon samples at day+4 after DSS induction from colitis-bearing and control mice, which received DsRed+ EPCs. Green A488-CD31 signal is vessel-related. Scale bar, 30 µm (A-C). Error bar indicates mean ± SEM. *P < .05 by Student t test (2-tailed).

No early incorporation of EPCs in experimental models of GVHD and IBD. (A) Number of proliferating (Ki67+) ECs in colon of SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (n = 3 per group). White arrow marks proliferating EC (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI+] [blue], Ki67+ [red-A555] in direct contact with CD31 [green-A488] signal). White asterisks mark proliferating crypt cells. (B) Representative pictures of green-A488 CD31 (vessel-related), DsRed (BM-related), and merged signals of colon and skin sections from SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (DsRed+C57BL/6→B6D2F1). (C) Representative pictures of green-A488 CD31, DsRed, and merged signals of colon sections from DsRed+ BM chimeras at day+4 after DSS colitis induction. (D) Representative projections of Z-stacks of colon samples at day+4 after DSS induction from colitis-bearing and control mice, which received DsRed+ EPCs. Green A488-CD31 signal is vessel-related. Scale bar, 30 µm (A-C). Error bar indicates mean ± SEM. *P < .05 by Student t test (2-tailed).

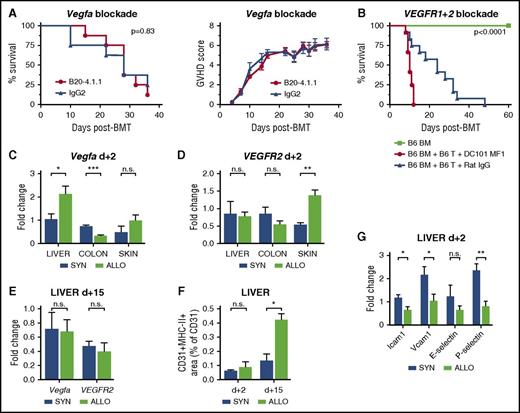

Effect of targeting angiogenesis in GVHD by blocking Vegfa/VEGFR pathway

We aimed at identifying pathways that are relevant for early angiogenesis during GVHD and initially investigated the Vegfa/VEGFR1+2 axis.29 Based on our previous observation demonstrating a reduction of GVHD due to inhibition of neovascularization by anti-VE-cadherin antibodies,4 we performed therapeutic interventions with monoclonal blocking antibodies. The anti-VEGFA antibody B20-4.1.1 had no significant effects on survival and GVHD scores during GVHD (Figure 3A). VEGFR1+2-blocking by administration of MF1 and DC101 led to inhibition of hematopoietic reconstitution (supplemental Figure 8) and decreased survival after allo-BMT (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we found no consistent upregulation of Vegfa and VEGFR2 expression levels in GVHD-target organs during the initiation of GVHD (Figure 3C,D) or later time points (Figure 3E). Taken together, our results argue against an important role of the Vegfa/VEGFR2 pathway for initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD target organs.

The Vegfa/VEGFR2 pathway and adhesion molecules are not upregulated during the initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD target organs. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve and GVHD scoring of B20-4.1.1 (Vegfa inhibitor) and rat IgG2-treated control mice (LP/J→C57BL/6) (n = 8 per group). (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of DC101+MFI (VEGFR1+2 inhibitor) and rat IgG–treated control mice (C57BL/6→BALB/c) (n = 12 per group). Untreated, only BM cell transplanted mice served as internal control (n = 5). Vegfa and VEGFR2 expression in GVHD target organs liver, colon, and skin of ALLO vs SYN mice (n = 5 per group) at day+2 after BMT (C-D) as well as in liver at day+15 after BMT (E). (F) MHC-II and CD31 double-positive area of CD31-positive area in liver of SYN and ALLO mice day+2 and +15 after BMT (n = 7 per group). (G) Expression of adhesion molecules Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (Icam1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (Vcam1), E-selectin, and P-selectin in MACS-sorted liver ECs from SYN vs ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (n = 5). In panels A-B, P values were calculated by using the log-rank test. In panels C-E,G, gene expression levels were normalized to Gapdh expression and are shown relative to gene levels of a reference untreated sample. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n.s. not significant by Student t test (2-tailed).

The Vegfa/VEGFR2 pathway and adhesion molecules are not upregulated during the initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD target organs. (A) Kaplan-Meier curve and GVHD scoring of B20-4.1.1 (Vegfa inhibitor) and rat IgG2-treated control mice (LP/J→C57BL/6) (n = 8 per group). (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of DC101+MFI (VEGFR1+2 inhibitor) and rat IgG–treated control mice (C57BL/6→BALB/c) (n = 12 per group). Untreated, only BM cell transplanted mice served as internal control (n = 5). Vegfa and VEGFR2 expression in GVHD target organs liver, colon, and skin of ALLO vs SYN mice (n = 5 per group) at day+2 after BMT (C-D) as well as in liver at day+15 after BMT (E). (F) MHC-II and CD31 double-positive area of CD31-positive area in liver of SYN and ALLO mice day+2 and +15 after BMT (n = 7 per group). (G) Expression of adhesion molecules Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (Icam1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (Vcam1), E-selectin, and P-selectin in MACS-sorted liver ECs from SYN vs ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (n = 5). In panels A-B, P values were calculated by using the log-rank test. In panels C-E,G, gene expression levels were normalized to Gapdh expression and are shown relative to gene levels of a reference untreated sample. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n.s. not significant by Student t test (2-tailed).

Expression levels of inflammation-associated endothelial activation markers in GVHD

We next investigated EC activation and adhesion molecules during early and established GVHD. ECs constitutively express MHC-I,30,31 which did not change after transplantation (supplemental Figure 9A,B). In a highly inflammatory environment at day+15, we found a significant increase in MHC-II+CD31+ area in liver of allo-BMT recipients, whereas in a leukocyte infiltration-free environment at day+2, no MHC-II upregulation occurred (Figure 3F). Typical for inflammatory diseases, we found increased expression levels of adhesion molecules, such as Icam1, Vcam1, E-, and P-selectin in GVHD target organs (supplemental Figure 10) during established GVHD at day+15. In sharp contrast, at day+2 MACS-isolated CD45dim+neg/CD11b−/CD31+ liver ECs of allo-BMT recipients (supplemental Figure 11A,B) showed significant downregulation of gene expression levels of these markers compared with syn-BMT recipients (Figure 3G). Our results demonstrate that initial endothelial activation follows a different pattern as compared with endothelial activation during established GVHD.

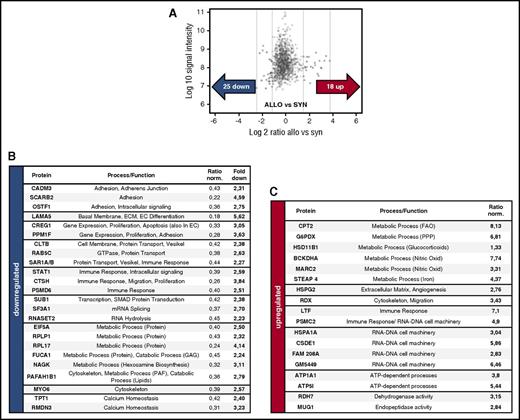

Metabolic and cytoskeleton changes in ECs lead to higher deformability

To identify pathways during the initiation of angiogenesis in an unbiased approach, we performed microarray analyses of FACS-sorted colon ECs in allo-BMT recipients vs syn-BMT recipients at day+2. Hierarchical clustering revealed profound differences in gene expression in colon ECs during the initiation of GVHD in allo-BMT vs syn-BMT (Figure 4A,C). To detect relevant changes on protein level during the initiation of angiogenesis, we performed LC-MS/MS proteome analyses of MACS-isolated liver ECs at day+2 after allo-BMT vs syn-BMT. We identified 18 upregulated and 25 downregulated proteins (Figure 5A-C) showing network connections (supplemental Figures 12 and 13). A list of significant upregulated and downregulated genes and proteins is given in supplemental Tables 1-4. Again, no upregulation of Vegfa and VEGFR2 was detected, and several adhesion molecules were downregulated, including Icam1, Muc1, CAMD3, SCARB2, and OSTF1. Strikingly, we detected substantial changes in the lipid and sphingolipid metabolism as well as in glycolysis of ECs during early GVHD in colon and liver on RNA level as well as on protein level (Figures 4B and 5B,C). In addition, we found several differentially regulated cytoskeleton-associated and -related genes (Tubal3, Myo3a, Scin, Ttll6) and proteins (RDX, MYO6) in colon and liver EC in initial GVHD (Figures 4B and 5B,C).

Microarray analysis of colon ECs reveals profound metabolic and cytoskeletal changes during initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD. (A) Hierarchical clustering of microarray data from colon ECs from ALLO and SYN mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) (n = 4 per group). Red and blue represent high and low levels of gene expression, respectively. (B) Selected pathways with involved genes being differentially expressed in ECs between ALLO and SYN mice. In supplemental Tables 1 and 2, a detailed list of gene symbols + names, fold changes, and P values is available. (C) Volcano plot for the expression of total genes (34 472 genes). Red and blue crosses represent 145 upregulated and 99 downregulated genes, respectively. (Fold Change [linear] < −2 or >2, analysis of variance P value (Condition pair) < .05).

Microarray analysis of colon ECs reveals profound metabolic and cytoskeletal changes during initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD. (A) Hierarchical clustering of microarray data from colon ECs from ALLO and SYN mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) (n = 4 per group). Red and blue represent high and low levels of gene expression, respectively. (B) Selected pathways with involved genes being differentially expressed in ECs between ALLO and SYN mice. In supplemental Tables 1 and 2, a detailed list of gene symbols + names, fold changes, and P values is available. (C) Volcano plot for the expression of total genes (34 472 genes). Red and blue crosses represent 145 upregulated and 99 downregulated genes, respectively. (Fold Change [linear] < −2 or >2, analysis of variance P value (Condition pair) < .05).

LC-MS/MS proteome analysis of liver ECs reveals profound metabolic and cytoskeletal changes during initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD. (A) LC-MS/MS proteome analysis of liver ECs at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) with 1518 proteins, and >24 000 peptides quantified revealed 25 proteins downregulated and 18 upregulated proteins between ALLO and SYN mice (n = 5 per group). (B-C) Table of downregulated and upregulated proteins with corresponding functions/mechanisms and normalized ratios. In supplemental Tables 3 and 4, a detailed list of protein symbols + names, cellular localization, and involved pathways is available. ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GAG, glycosaminoglycans; PAF, platelet activating factor; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway.

LC-MS/MS proteome analysis of liver ECs reveals profound metabolic and cytoskeletal changes during initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD. (A) LC-MS/MS proteome analysis of liver ECs at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) with 1518 proteins, and >24 000 peptides quantified revealed 25 proteins downregulated and 18 upregulated proteins between ALLO and SYN mice (n = 5 per group). (B-C) Table of downregulated and upregulated proteins with corresponding functions/mechanisms and normalized ratios. In supplemental Tables 3 and 4, a detailed list of protein symbols + names, cellular localization, and involved pathways is available. ATP, adenosine triphosphate; GAG, glycosaminoglycans; PAF, platelet activating factor; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway.

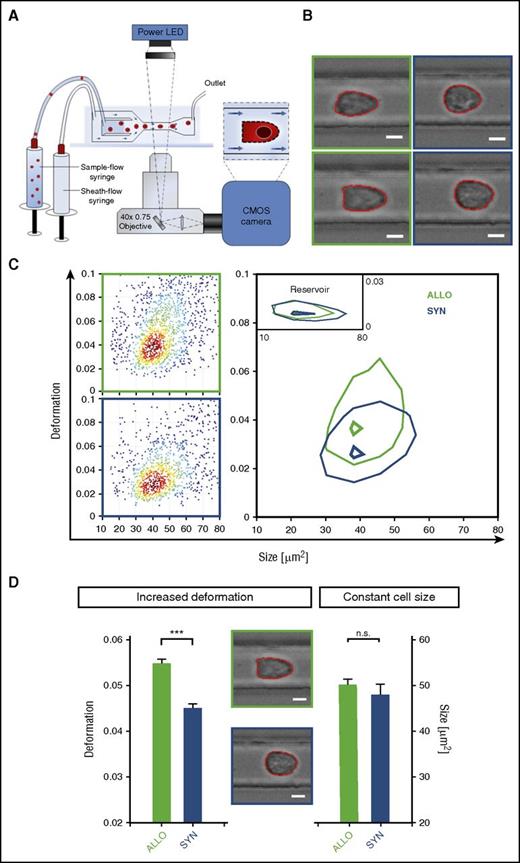

To investigate if metabolic and cytoskeletal changes in ECs during the initiation of GVHD have functional consequences, we measured single-cell mechanical characteristics at high speed with RT-DC26 (Figure 6A). ECs from allo-BMT recipients and syn-BMT recipients at day+2 displayed heterogeneity in cell shape (Figure 6B). Liver ECs from allo-BMT recipients showed a significantly higher deformation (D = 0.0547 ± 0.0011) as compared with ECs from syn-BMT recipients (D = 0.0451 ± 0.0010) (Figure 6C-D) at day+2 after BMT. This deformation is attended by the overall softening of ECs during the initiation of GVHD. The cell size was not affected (Figure 6D). In addition to the observed downregulation of cell-cell contact proteins and the upregulation of cytoskeleton-associated proteins (described above), the EC softening indicates an enhanced migratory potential.

Early modifications in ECs have significant functional consequences as indicated by profoundly higher deformation in RT-DC. (A) RT-DC setup and measurement principle (inset shows top view of constriction). (B) Representative images of liver ECs from ALLO (green square) and SYN (blue square) mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) acquired by RT-DC. (C) RT-DC measurements. Scatter plot of deformation vs cell size (cross-sectional area) of 1510 cells (dots). Color indicates a linear density scale. Density contour plots (50%) of ALLO vs SYN mice. (D) Mechanical phenotyping of liver ECs of ALLO and SYN mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6). Mean values n = 3. Deformation P = .0002, size P = .285 (***P ≤ .001) by a likelihood ratio test. Images are analyzed for cell size and cell shape (red contours). Scale bar, 5 µm. CMOS, complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor; LED, light-emitting diode.

Early modifications in ECs have significant functional consequences as indicated by profoundly higher deformation in RT-DC. (A) RT-DC setup and measurement principle (inset shows top view of constriction). (B) Representative images of liver ECs from ALLO (green square) and SYN (blue square) mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) acquired by RT-DC. (C) RT-DC measurements. Scatter plot of deformation vs cell size (cross-sectional area) of 1510 cells (dots). Color indicates a linear density scale. Density contour plots (50%) of ALLO vs SYN mice. (D) Mechanical phenotyping of liver ECs of ALLO and SYN mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6). Mean values n = 3. Deformation P = .0002, size P = .285 (***P ≤ .001) by a likelihood ratio test. Images are analyzed for cell size and cell shape (red contours). Scale bar, 5 µm. CMOS, complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor; LED, light-emitting diode.

Discussion

It is well known that inflammatory diseases are associated with angiogenesis. The proposed mechanism for this association is an induction of angiogenesis by secreted mediators of tissue infiltrating inflammatory cells.6,7 In this study, we provide novel evidence on a primary involvement of angiogenesis in the initiation of tissue inflammation prior to infiltration of inflammatory cells. We demonstrate that angiogenesis precedes leukocyte infiltration during inflammation in animal models of GVHD. We confirmed our finding in an experimental model of IBD, implicating a broader significance of our results surpassing the field of transplantation biology.

Our current results add further data to the accumulating evidence on the significant importance of endothelial function for the pathophysiology of GVHD. Findings from preclinical models, demonstrating that GVHD is associated with the formation of new blood vessels, were confirmed in humans.2-5 Furthermore, endothelial pathology was specifically connected to mortality in patients with GVHD.32,33 First mechanistic insights in therapeutic targeting angiogenesis by inhibiting the endothelial adhesion molecules VE-cadherin and αv integrin in murine GVHD models potentially opened a new field of GVHD treatment options.2-4 In the present study, we found that initial angiogenesis specifically arose after allo-BMT independently from syn-BMT or conditioning underlining the particular role of angiogenesis for GVHD pathogenesis.

Our results can be used as rationale for the translational development of anti-inflammatory therapies aimed at angiogenesis. With our finding that certain metabolic and cytoskeleton changes are involved in the initiation of inflammatory angiogenesis, we provide potential targets for anti-inflammatory therapies aimed at angiogenesis. Recent research has demonstrated that metabolic processes are linked to increased proliferative activity and vessel sprouting.11-15,17,34-36 Inhibition of glycolysis by the 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase inhibitor 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one (3PO)17,37 as well as inhibition of FAO by etomoxir15 showed beneficial antiangiogenic effects in several inflammatory models. Interestingly, FAO inhibitors such as ranolazine or perhexiline are clinically available and showed good drug tolerability in humans.38 Glycolysis has been shown to be associated with remodeling of the cytoskeleton during EC migration and angiogenesis.16,36 Accordingly, we found several differentially regulated cytoskeleton-associated and cytoskeleton-related genes and proteins in colon and liver EC in initial GVHD. Cell shape alterations by the cytoskeleton were shown to be critical for various steps of angiogenesis.39 Cytoskeletal remodeling–dependent elevated proliferation was previously shown to soften cells in vitro.25,40 We used a novel method, termed RT-DC,26 to demonstrate that cytoskeleton changes result in higher deformability of ECs during the initiation of inflammation leading to increased proliferation and migration potential. The endothelial cytoskeleton can be efficiently targeted by microtubule depolymerizing agents belonging to the large group of small molecular weight vascular disrupting agents. Several of them, including the lead compound disodium combretastatin A-4 3-O-phosphate, are currently under clinical development for cancer.41-44 In addition, there are new approaches to directly target ECs, eg, by a multimodular recombinant protein, E-selectin-specific “sneaking ligand construct” 1 (SLC1), which only binds to cytokine-activated ECs, providing the opportunity to minimize toxicity and off-target effects.45 However, before translating our results into the clinical setting, functional analyses of pathways and therapeutic targets in preclinical models are needed. In addition, it has to be considered that the endothelium is damaged during conditioning therapy and during later phases of GVHD. Possible unwanted effects of antiangiogenic therapy on endothelial regeneration in these settings have to be addressed prior to translation of such therapeutic approaches.

The optimal schedule of an antiangiogenic treatment in inflammatory diseases represents a challenging question.9 We showed that angiogenesis occurred as early as day+2 after BMT. Our data are in line with previous observations demonstrating that angiogenesis can be a dynamic and fast process during trauma, inflammation, and cancer growth.46,47 Under conditions requiring rapid angiogenesis, such as wound healing, the microenvironment is quickly shifted, enabling development of new vessels within days.48,49 As immune cell infiltration is known to contribute to resistance against antiangiogenic drugs,50,51 starting a therapy prior to that could diminish these mechanisms as well as inflammatory-associated side effects. In the setting of GVHD, it offers the opportunity to initiate treatment early and potentially prevent or initially minimize disease outbreak.

Our current data argue against an important role of the Vegfa/VEGFR-1/2 pathway for GVHD pathophysiology. The role and dynamics of VEGF differ in human GVHD; whereas several studies showed no change52 or even decreased53-55 circulating VEGFA levels, Medinger et al5 detected an increase in VEGF+ megakaryocytes going in line with increased VEGF levels found by Porkholm et al56 in pediatric GVHD patients. However, this study only applied a univariate analysis. In a univariate and multivariate study by Luft et al, VEGF levels were not found to be predictive in GVHD; only during refractory GVHD were angiopoetin2/VEGFA ratios higher.57 Detected differences in VEGF levels may occur due to different posttransplant time points of determination, different measurement assays, VEGF sources (eg, serum in patients vs organ biopsies in our study), or varying GVHD progression. For example, severe course of GVHD was found associated with activation and infiltration of macrophages,58-61 which are known to be a source of VEGF.62-64 The clinical setting in GVHD is variable due to different drug applications, particularly preexisting diseases or treatments, which modify a growth factor pathway in many ways. These findings underline the importance of identifying VEGF-independent pathways and treatment options during pathogenic angiogenesis.29,65

During inflammatory activation, ECs can upregulate MHC-II and also exhibit antigen-presenting properties as described in human allografts66 and various inflammatory diseases, eg, rheumatoid arthritis.67 In a highly inflammatory tissue environment during established GVHD, we found increased expression levels of adhesion molecules responsible for leukocyte trafficking and endothelial activation in GVHD target organs, which confirms previous knowledge.68,69 In contrast, we found that initial endothelial activation during GVHD is not associated with upregulation of adhesion molecules and MHC-II, which is in line with results from patient biopsies during early GVHD.70,71 A similar EC phenotype with reduced expression of adhesion molecules has been demonstrated in malignant tumors during pathological angiogenesis.72-74 Our data demonstrate that early angiogenesis during the initiation of inflammation differs from the EC activation pattern, which is found during established tissue inflammation.

In conclusion, we provide novel insights into the initiation phase of inflammation and in GVHD pathophysiology. Our study adds evidence to the hypothesis that angiogenesis is involved in the initiation of tissue inflammation during inflammatory diseases. Our results strengthen the scientific rationale, and provide potential therapeutic targets, for development of antiangiogenic therapies to inhibit inflammation.

The data reported in this article have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE84119) and in the ProteomeXchange (accession number PXD004606).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sabine Schmidt and Giannino Patone (Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany) for generating the microarray data.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (PE1450/3-1), the Deutsche Krebshilfe (110466), the DKMS Stiftung Leben Spenden (DKMS-SLS-MHG-2016-02), the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2010_A104), the José Carreras Leukämie-Stiftung (R11/04; 11R2016), the Monika Kutzner Stiftung, the Stefan-Morsch-Stiftung (2013.06.29), the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung (2010.039.1; 2014.150.1), and the Kommission für Nachwuchsförderung of the Charité University Medicine.

Authorship

Contribution: K.R., Y.S., J.M., and O.P. designed the study; K.R., M. Kalupa, A.M., S.M., S.C., J.M., and S.W. performed GVHD and colitis experiments; A.J., M. Kräter, and J.G. performed real-time deformability experiments; J.-F.S. performed FACS; D.P.-H. and G.D. performed MS experiments; K.R. analyzed data; and K.R., A.J., M. Kräter, C.S., and O.P. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.W. is Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care and Pain Therapy, University Hospital Frankfurt, Frankfurt/Main, Germany.

The current affiliation for G.D. is Proteome and Genome Research Unit, Luxembourg Institute of Health, Strassen, Luxembourg.

Correspondence: Katarina Riesner, Department of Hematology, Oncology and Tumor Immunology, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Augustenburger Platz 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: katarina.riesner@charite.de.

![Figure 2. No early incorporation of EPCs in experimental models of GVHD and IBD. (A) Number of proliferating (Ki67+) ECs in colon of SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (n = 3 per group). White arrow marks proliferating EC (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI+] [blue], Ki67+ [red-A555] in direct contact with CD31 [green-A488] signal). White asterisks mark proliferating crypt cells. (B) Representative pictures of green-A488 CD31 (vessel-related), DsRed (BM-related), and merged signals of colon and skin sections from SYN and ALLO mice at day+2 after BMT (DsRed+C57BL/6→B6D2F1). (C) Representative pictures of green-A488 CD31, DsRed, and merged signals of colon sections from DsRed+ BM chimeras at day+4 after DSS colitis induction. (D) Representative projections of Z-stacks of colon samples at day+4 after DSS induction from colitis-bearing and control mice, which received DsRed+ EPCs. Green A488-CD31 signal is vessel-related. Scale bar, 30 µm (A-C). Error bar indicates mean ± SEM. *P < .05 by Student t test (2-tailed).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/14/10.1182_blood-2016-08-736314/4/m_blood736314f2.jpeg?Expires=1769117458&Signature=Z7yHtFu4wmwUXZq7RuvUOm4Vq2dIBtEJ-IPz0LwvAExAxcCFMkogtqQgPjE-KKKunc4AFQ0jgQApeyYoR2NrTOyvSoWiuVO-d7kPB8bXIOyUqqnVAFyMsjgzx0pCNivzg5Su82w39NqPQdd~rktPHkv6qZpFd1QajqLMGonKJekuvUu44n~Sc9uVMXhNzOnItMZfMt1uxBgh7IKBqwNxHHXysg4K0yywT-l4l-u180JWAB9QjEoSoobDJciN-iPkixYhBHLYgHvnsd0mVcwIyJ5S5jY~Wk8tOR6WyJpl3pgRwhmj2jev6m9I9qZR~p~4I4dUL1TsREq9uyoE32JrvA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Microarray analysis of colon ECs reveals profound metabolic and cytoskeletal changes during initiation of angiogenesis in GVHD. (A) Hierarchical clustering of microarray data from colon ECs from ALLO and SYN mice at day+2 after BMT (LP/J→C57BL/6) (n = 4 per group). Red and blue represent high and low levels of gene expression, respectively. (B) Selected pathways with involved genes being differentially expressed in ECs between ALLO and SYN mice. In supplemental Tables 1 and 2, a detailed list of gene symbols + names, fold changes, and P values is available. (C) Volcano plot for the expression of total genes (34 472 genes). Red and blue crosses represent 145 upregulated and 99 downregulated genes, respectively. (Fold Change [linear] < −2 or >2, analysis of variance P value (Condition pair) < .05).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/14/10.1182_blood-2016-08-736314/4/m_blood736314f4.jpeg?Expires=1769117458&Signature=ypJIAXke-J~ANPJHYciFzsPPiyfPIxM8PDxJI~CgjI00L9Nl2yR7WbqQnmnuF3RNVJ47tNo85T02GPjEseFM0zx9RGfuI4dXpTB4JYA5A5~CpwlAmLl1~xih~~EKBGarcRsdoadQzs5vduUsNCMqEI9ojW3dIQsvbgUgfmW~OHZwpBTQtmLza8GmnXX59rYxvEoBJ6KEX0lU8CQfN1NqMgZc4vjdIB9BSyzXO7jhIQNFuKFgJb2Psp9V3Ijx9k5tZjcSiRdQfU1gsLJemCZettjNOBJARheXN8NHrX1Ri-rchyR7Zi86ZNQUY1ewNRwTX7pUCLjzoNeVTmMYSt6JYQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal