Key Points

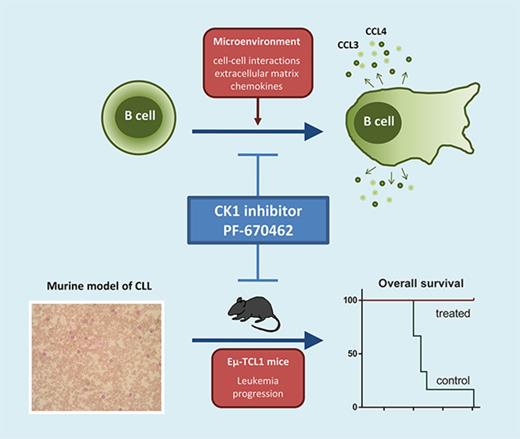

CK1 inhibition significantly blocks microenvironmental interactions of CLL cells.

CK1 inhibition slows down development of CLL-like disease in the Eμ-TCL1 mouse model.

Abstract

Casein kinase 1δ/ε (CK1δ/ε) is a key component of noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways, which were shown previously to drive pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). In this study, we investigated thoroughly the effects of CK1δ/ε inhibition on the primary CLL cells and analyzed the therapeutic potential in vivo using 2 murine model systems based on the Eµ-TCL1–induced leukemia (syngeneic adoptive transfer model and spontaneous disease development), which resembles closely human CLL. We can demonstrate that the CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 significantly blocks microenvironmental interactions (chemotaxis, invasion and communication with stromal cells) in primary CLL cells in all major subtypes of CLL. In the mouse models, CK1 inhibition slows down accumulation of leukemic cells in the peripheral blood and spleen and prevents onset of anemia. As a consequence, PF-670462 treatment results in a significantly longer overall survival. Importantly, CK1 inhibition has synergistic effects to the B-cell receptor (BCR) inhibitors such as ibrutinib in vitro and significantly improves ibrutinib effects in vivo. Mice treated with a combination of PF-670462 and ibrutinib show the slowest progression of disease and survive significantly longer compared with ibrutinib-only treatment when the therapy is discontinued. In summary, this preclinical testing of CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 demonstrates that CK1 may serve as a novel therapeutic target in CLL, acting in synergy with BCR inhibitors. Our work provides evidence that targeting CK1 can represent an alternative or addition to the therapeutic strategies based on BCR signaling and antiapoptotic signaling (BCL-2) inhibition.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a lymphoproliferative disorder defined by the accumulation of clonal B lymphocytes with typical immunophenotypic profile (CD5, CD19, CD23, ROR1 positive) in peripheral blood (PB), bone marrow (BM), and lymphoid organs.

It has been recognized that CLL is driven by multiple signaling pathways, primarily promoting interaction with protective microenvironment and subsequently survival and proliferation of the malignant cells.1-3 Signaling machineries mediating communication with microenvironment, mainly B-cell receptor (BCR) and chemokine-induced signaling pathways, have become the main focus of novel therapeutic strategies with BCR-associated kinase inhibitors, such as ibrutinib (Bruton tyrosine kinase [BTK] inhibitor) and idelalisib (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K] δ inhibitor).

Recently, noncanonical Wnt/planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway, driven by ROR1 receptor,4-6 has been recognized as an additional mechanism required for the communication of CLL cells with their microenvironment involved in CLL pathogenesis. Wnt/PCP drives the pathogenesis of CLL primarily via regulation of chemotaxis and cell polarity,7-11 but reports demonstrating effects on survival and proliferation also exist.11 These clinical observations were functionally supported by genetic analysis of the Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mouse model of CLL where overexpression of Wnt/PCP receptor, ROR1, enhanced leukemogenesis,12 whereas elimination of FRIZZLED 6, another component of the Wnt/PCP receptor complex, delayed CLL development.13 Importantly, although best studied in CLL, the Wnt/PCP pathway can have similar importance also in other lymphoid malignancies.14-17

Based on these facts, we hypothesized that the Wnt/PCP pathway can represent a potential therapeutic target in CLL. We have shown previously that casein kinase 1δ/ε (CK1δ/ε) activity is indispensable for Wnt/PCP signaling in the context of CLL7,8,18 and as such may serve as a druggable component in the Wnt/PCP pathway relevant for CLL. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effects of CK1δ/ε inhibition on the behavior of primary CLL cells with a focus on the CLL-microenvironment communication and on the leukemia development and progression in vivo using 2 murine model systems based on Eµ-TCL1–induced leukemia. Our work provides evidence that targeting CK1 is an alternative to the therapeutic strategies based on BCR and antiapoptotic signaling (BCL-2) inhibition.

Methods

Primary CLL samples, healthy controls, and cell lines

Primary cells were isolated from PB of CLL patients monitored and treated at the Department of Internal Medicine–Hematology and Oncology, University Hospital Brno, according to international criteria.19 All samples including age-matched nonmalignant controls were taken after written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki under protocols approved by the Ethical Committee of the University Hospital Brno. Cells were separated using non–B-cell depletion techniques (RosetteSep kits; StemCell).7 The separation efficiency was assessed by flow cytometry, and all tested samples contained ≥98% B cells in the case of CLL cells and 70% to 80% in the case of nonmalignant controls. Basic clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site). MEC-120 cells (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH) and HEK293T and M210B421 cells (both American Type Culture Collection) were used as model cell lines. Cell culture conditions are described in the supplemental Data.

Cell treatments

The following chemicals were used for in vitro experiments: 10 to 150 µM PF-4800567 (RnD Systems), 0.03 to 50 µM PF-670462 (Tocris; DC Chemicals), 5 to 125 µM D4476 (Calbiochem), and 0.03 to 3 µM ibrutinib (PCI-32765; DC Chemicals). Control conditions contained the corresponding amount of dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma Aldrich). Viability of cells was assessed in parallel by staining with tetramethylrhodamine (2 μM, 15 minutes at room temperature; Invitrogen) or according to cell morphology, based on flow cytometric analysis (forward vs side scatter).

Functional in vitro experiments

Detailed protocols of the transwell migration assay, double-species coculture system and analysis of CCL3/4 levels produced by CLL cells (gene expression and protein secretion), CK1ε autophosphorylation assay for assessment of CK1ε activity, BCR pathway-stimulation, and subsequent western blotting analysis are all described in detail in the supplemental Data.

Animals

All animal experiments were performed with approval of the Ethics Committee in accordance with the international ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.22 The Eµ-TCL123 mouse model system is described in detail in the supplemental Data. Disease progression was monitored by regular PB sampling followed by flow cytometric analysis as described previously12 and in the supplemental Data, which enabled quantification of white blood cells (WBCs) as well as distinct lymphocyte populations: leukemic B cells (CD5lowCD45Rlow), normal B cells (CD5negCD45Rhigh), and T cells (CD5highCD45Rneg). Analysis was performed on a BD Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer, and data were analyzed by BD Accuri C6 Software. Hematological analysis of PB was performed by hemoanalyzer Mindray BC-5300VET (Mindray). Spleen volume was monitored by high-frequency ultrasound VEVO 2100 System (FUJIFILM Visual Sonic; measured at 30 MHz) and analyzed by the VEVO 2100 software. For this application, animals were anesthetized by isofurane gas.

Statistics

All statistical tests were performed as 2-sided using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc.; described in detail in the supplemental Data). Asterisks were used in graphs to visualize P values: *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001; n.s. indicates “not significant.” The standard level of statistical significance was P ≤ .05.

Results

CK1ε is upregulated in CLL, and inhibition of CK1ε blocks CLL chemotaxis

To support the hypothesis that CK1ε is not only a key molecule of the Wnt/PCP pathway, but also a suitable target for CLL therapy, we have analyzed the expression profile of CSNK1E, encoding for CK1ε, using microarray data publicly available in the Oncomine database.24 The 2 independent data sets25,26 provide evidence that CSNK1E is overexpressed in CLL cells compared with nonmalignant B-cell populations in PB (Figure 1A) and BM (supplemental Figure 1A). Interestingly, the expression levels were comparably low between naïve and memory PB B cells isolated from healthy donors (Figure 1A). This upregulation translates into increased protein levels of CK1ε in CLL cells compared with nonmalignant B cells (Figure 1Bi-ii). This confirms our earlier findings7 and suggests that CK1ε can be a druggable target with different expression in CLL and healthy B cells, similarly to the ROR1 receptor.4-6

CK1ε is upregulated in CLL, and its activity is inhibited by PF-670462 inhibitor at low micromolar concentration. (A) CSNK1E expression (probe 38019_at); microarray data obtained from the Oncomine database24 (‘Basso Lymphoma’ data set25 ). CLL PB samples (N = 34) compared with nonmalignant PB B-cell populations: naïve (N = 5) and memory (N = 5) (1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < .0001). Black lines represent median. (B) Protein levels in primary CLL samples (N = 6) and healthy controls (buffy coats, N = 3) were analyzed by western blotting (i). Quantification of detected CK1ε levels performed by ImageJ software (P = .0310, unpaired Student t test) (ii). CK1ε protein level in MEC-1 cell line in comparison with primary CLL and healthy control samples (iii). Activity of CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 was tested in a transwell migration assay (6 hours, CCL19-induced chemotaxis) using MEC-1 cell line (C; N = 3) and 4 freshly isolated primary CLL samples (D). Relative migration index (left y-axis, red) represents ratio between cells migrated toward chemokine in the inhibitor-treated and control conditions. Viability (right y-axis, blue) was tested in parallel by tetramethylrhodamine staining. Vertical dashed lines represent EC50 values. Symbols represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (E) Activity of CK1ε after PF-670462/dimethyl sulfoxide treatment (2 hours) in primary CLL cells stimulated by 50 nM Calyculin A (1 hour); upper band represents autophosphorylated form (PS-CK1ε), which is not present in an unstimulated sample and is lost dose-dependently upon CK1ε inhibition with maximum effect at 10 µM concentration. Representative result is presented (N = 3).

CK1ε is upregulated in CLL, and its activity is inhibited by PF-670462 inhibitor at low micromolar concentration. (A) CSNK1E expression (probe 38019_at); microarray data obtained from the Oncomine database24 (‘Basso Lymphoma’ data set25 ). CLL PB samples (N = 34) compared with nonmalignant PB B-cell populations: naïve (N = 5) and memory (N = 5) (1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < .0001). Black lines represent median. (B) Protein levels in primary CLL samples (N = 6) and healthy controls (buffy coats, N = 3) were analyzed by western blotting (i). Quantification of detected CK1ε levels performed by ImageJ software (P = .0310, unpaired Student t test) (ii). CK1ε protein level in MEC-1 cell line in comparison with primary CLL and healthy control samples (iii). Activity of CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 was tested in a transwell migration assay (6 hours, CCL19-induced chemotaxis) using MEC-1 cell line (C; N = 3) and 4 freshly isolated primary CLL samples (D). Relative migration index (left y-axis, red) represents ratio between cells migrated toward chemokine in the inhibitor-treated and control conditions. Viability (right y-axis, blue) was tested in parallel by tetramethylrhodamine staining. Vertical dashed lines represent EC50 values. Symbols represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (E) Activity of CK1ε after PF-670462/dimethyl sulfoxide treatment (2 hours) in primary CLL cells stimulated by 50 nM Calyculin A (1 hour); upper band represents autophosphorylated form (PS-CK1ε), which is not present in an unstimulated sample and is lost dose-dependently upon CK1ε inhibition with maximum effect at 10 µM concentration. Representative result is presented (N = 3).

As the next step, we have assayed 3 commercially available compounds reported to inhibit CK1δ and/or CK1ε. The tested compounds (PF-4800567, PF-670462, and D4476) were selected because of their low 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values and well-characterized specificity. All compounds are adenosine triphosphate–competing CK1 inhibitors. PF-4800567 displays 22-fold greater potency toward CK1ε than CK1δ (IC50 values of 32 nM for CK1ε and 711 nM for CK1δ),27 the PF-670462 compound is a potent and selective inhibitor of both isoforms (IC50 values of 7.7 nM for CK1ε and 14 nM for CK1δ),28 whereas D4476 is a less specific CK1δ and ALK5 inhibitor (IC50 values of 0.2 μM and 0.5 μM, respectively).29

Using the well-established transwell migration assay,7 we have quantified effects of the inhibitors on chemotaxis of the MEC-1 cell line, originating from CLL prolymphocytic transformation,20 which was shown to express high levels of CK1ε and other Wnt/PCP pathway components7 (Figure 1Biii) with the exception of the ROR1 receptor.11 All inhibitors reduced significantly MEC-1 chemotaxis toward CCL19 chemokine (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1Bi-ii, left y-axis, in red) but did not affect cell viability during the 6-hour migration protocol (right t-axis, in blue). PF-670462 inhibitor was the most potent (50% effective concentration [EC50] = 2.4 μM) with >20 times lower EC50 than the other inhibitors (PF-4800567, EC50 = 72.1 μM; D4476, EC50 = 88.0 μM) and as such was used in further experiments. Findings from the MEC-1 model were confirmed for primary CLL cells; in the same experimental settings, the EC50 value was determined as 2.8 μM in the case of freshly isolated CLL cells (Figure 1D) and 0.18 μM for primary CLL cells that went through a freeze-thaw cycle (supplemental Figure 1Biii). Certain variability was observed among individual CLL patients (see supplemental Figure 1C-D), with EC50 ranging from 1.8 to 6.2 μM. To confirm efficient inhibition of CK1ε activity in the in-cell assays, we have performed CK1 autophosphorylation assay in 3 primary CLL samples (Figure 1E). Results showed that the kinase is almost completely inhibited at 10 μM concentration; therefore, this dose was selected for further testing, and experiments were performed exclusively with fresh primary samples with the exception of the experiment presented in Figure 6G and related supplemental Data.

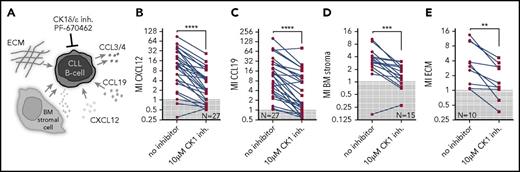

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 efficiently blocks interactions with the microenvironment in all major subgroups of CLL patients

In order to analyze the ability of CK1 inhibitor PF-670462 to block various means of the interaction of CLL cells with microenvironmental components, we have performed the following set of experiments using primary CLL cells: chemotaxis toward chemokines (1) CXCL12 and (2) CCL19 involved in the process of B-cell/CLL cell homing to lymphoid organs and BM; (3) chemotaxis toward BM stromal cells, which provide complex and less defined mixture of stimulatory factors; and (4) integrin-mediated cell adhesion boosted by fibronectin, a component of extracellular matrix (ECM), which increases migration of CLL cells30 (Figure 2A). The effects of CK1 inhibitor were analyzed using transwell assays. All microenvironmental stimuli were able to promote chemotaxis of primary CLL cells, albeit to a different extent. Importantly, we demonstrated that CK1 inhibition significantly decreased migration index in all tested conditions (Figure 2B-E). These data provide evidence that the CK1 inhibition is a highly effective approach to block CLL cell chemotaxis.

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 specifically blocks interaction of primary CLL cells with microenvironmental stimuli in vitro. (A) Scheme of the applied treatments and analyzed CLL-microenvironment interactions. (B-E) Migration of primary CLL cells (N = 10-27) in presence or absence of PF-670462 was assayed using transwell assays. Cells were stimulated by 200 ng/mL CXCL12 (B) or CCL19 (C), BM stromal cells M210B4 (D), or ECM component fibronectin (E) stimulation. CK1 inhibitor treatment significantly blocked response to chemokines (P < .0001 both for CXCL12 and CCL19, N = 27), BM stroma (P < .0001, N = 15), and ECM (P = .0020, N = 10). MI, migration index.

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 specifically blocks interaction of primary CLL cells with microenvironmental stimuli in vitro. (A) Scheme of the applied treatments and analyzed CLL-microenvironment interactions. (B-E) Migration of primary CLL cells (N = 10-27) in presence or absence of PF-670462 was assayed using transwell assays. Cells were stimulated by 200 ng/mL CXCL12 (B) or CCL19 (C), BM stromal cells M210B4 (D), or ECM component fibronectin (E) stimulation. CK1 inhibitor treatment significantly blocked response to chemokines (P < .0001 both for CXCL12 and CCL19, N = 27), BM stroma (P < .0001, N = 15), and ECM (P = .0020, N = 10). MI, migration index.

CLL patients can be categorized into multiple subgroups, differing in their clinical and molecular characteristics. In order to assess differences in response to CK1 inhibition among individual CLL subtypes, we have stratified the patients analyzed in Figure 2B-E using prognostic parameters such as immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) status, Rai stage, hierarchical cytogenetics, or the therapy status at the time of sampling (for complete overview of the cases entering this analysis, see supplemental Table 1). Results of this analysis are summed up in Table 1 (raw migration data are shown in supplemental Figure 2A-D; data are presented as percent of control in supplemental Figure 2E-H). Overall, the migration was significantly reduced by CK1 inhibition in all patient subgroups with enough data for statistical analysis.

CLL patient samples analyzed in Figure 2B-E

| . | IGHV . | Rai at sampling . | Hierarchical cytogenetics . | Therapy . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-CLL . | U-CLL . | 0 . | I-II . | III-IV . | High risk . | Others . | Treated . | Untreated . | |

| CXCL12 | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 31 (16) | 26 (11) | 26 (10) | 34 (8) | 34 (9) | 24 (6) | 34 (21) | 32 (13) | 30 (14) |

| P* | <.0001 | .0029 | .002 | .0015 | .0117 | .0014 | <.0001 | .0002 | .0002 |

| CCL19 | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 34 (16) | 29 (11) | 30 (10) | 40 (8) | 29 (9) | 26 (6) | 33 (21) | 28 (13) | 40 (14) |

| P* | .0042 | .001 | .0488 | .004 | .0117 | .0023 | .0006 | .0012 | .004 |

| BM stroma | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 32 (4) | 54 (11) | 53 (1) | 67 (6) | 26 (8) | 53 (7) | 46 (8) | 37 (13) | 65 (2) |

| P* | .0365 | .002 | — | .023 | .0148 | .0313 | .0041 | .0005 | — |

| ECM | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 41 (6) | 45 (4) | 95 (1) | 50 (4) | 35 (5) | 21 (3) | 46 (7) | 36 (6) | 83† (4) |

| P* | .0313 | .0452 | — | .0419 | .0133 | 0.0663 | .0117 | .0313 | 0.2069 |

| . | IGHV . | Rai at sampling . | Hierarchical cytogenetics . | Therapy . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-CLL . | U-CLL . | 0 . | I-II . | III-IV . | High risk . | Others . | Treated . | Untreated . | |

| CXCL12 | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 31 (16) | 26 (11) | 26 (10) | 34 (8) | 34 (9) | 24 (6) | 34 (21) | 32 (13) | 30 (14) |

| P* | <.0001 | .0029 | .002 | .0015 | .0117 | .0014 | <.0001 | .0002 | .0002 |

| CCL19 | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 34 (16) | 29 (11) | 30 (10) | 40 (8) | 29 (9) | 26 (6) | 33 (21) | 28 (13) | 40 (14) |

| P* | .0042 | .001 | .0488 | .004 | .0117 | .0023 | .0006 | .0012 | .004 |

| BM stroma | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 32 (4) | 54 (11) | 53 (1) | 67 (6) | 26 (8) | 53 (7) | 46 (8) | 37 (13) | 65 (2) |

| P* | .0365 | .002 | — | .023 | .0148 | .0313 | .0041 | .0005 | — |

| ECM | |||||||||

| % of Control, median (N) | 41 (6) | 45 (4) | 95 (1) | 50 (4) | 35 (5) | 21 (3) | 46 (7) | 36 (6) | 83† (4) |

| P* | .0313 | .0452 | — | .0419 | .0133 | 0.0663 | .0117 | .0313 | 0.2069 |

CLL patient samples analyzed in Figure 2B-E were divided into groups based on their clinical and molecular characteristics. Stratification was based on IGHV mutational status (mutated [M-CLL] and unmutated [U-CLL] IGHV); Rai stage at sampling (groups 0/I-II/III-IV; stage II and IV); hierarchical cytogenetics [high risk (del 11q and del 17p) vs others (del 13q, normal karyotype, tris 12)]; and prior therapy (treated vs untreated). For full data, see supplemental Figure 2E-H. Results are summarized for each group in the following format: median percentage of control, number of samples (N), and statistical significance (P). Raw data (migration index [MI] values, supplemental Figure 2A-D) were analyzed by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or ratio paired Student t test according to the data distribution. Significant P values are shown in bold.

—, Not applicable.

Control vs CK1 inhibitor treated MI; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test or ratio paired Student t test according to the data distribution.

Inhibitory effects were significantly different between groups.

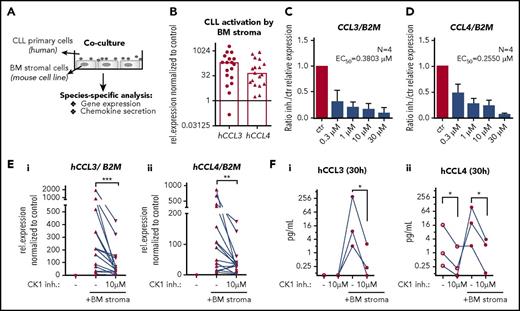

CK1δ/ε inhibition blocks production of CCL3/4 by CLL cells in a coculture system

Microenvironment can induce transcription of genes that help CLL cells to survive or shape their own environment, for example by production of T-cell chemokines CCL3 or CCL4 contributing to the formation of lymph node pseudofollicles.31,32 In order to address this issue, we employed a double-species coculture system, where the primary human CLL cells interacted directly with the mouse BM stromal cells M210B421 (Figure 3A). These complex interactions resulted in a robust increase in the expression of CCL3 and CCL4 that could be quantified by human-specific quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis, which allows for absolute control over specificity of the detected gene expression. In our cohort of 18 patient samples, 15 upregulated both CCL3 and CCL4 (defined as at least fivefold increase; median fold increase 211× and 88×, respectively) (Figure 3B). Addition of CK1 inhibitor dose dependently reduced the induction of CCL3 and CCL4 expression in 4 analyzed CLL samples (Figure 3C-D) with estimated EC50 values below 0.5 µM. The effects were confirmed on a larger number of patients (N = 15; Figure 3E; supplemental Figure 3A-B) and further validated by human-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of CCL3 and CCL4 chemokines secreted to culture medium by CLL cells in this experimental set up (N = 3; Figure 3F). CXCL12/CCL19 chemokines or fibronectin alone were not considered as suitable stimuli for this type of analysis, because their ability to induce CCL3/4 expression in CLL cells was negligible compared with effects of M210B4 cells (supplemental Figure 3C). Overall, we provide evidence that CK1 activity is important also for cell-cell interactions and that CK1 inhibitor specifically blocks microenvironment-induced transcription in CLL cells.

CK1δ/ε inhibition blocks production of CCL3 and CCL4 by CLL cells in a coculture system. (A) Scheme of coculture experiments. (B) Expression of human CCL3 and CCL4 was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using human-specific primers in samples containing cocultured primary CLL and mouse stromal cells (N = 18). Relative change in the expression (with/without coculture) is shown. Columns represent median. (C-D) CK1 inhibitor treatment dose dependently (0.3-10 µM) inhibits the stroma-induced expression of CCL3/4 in CLL cells. EC50 values were estimated by nonlinear fit method (log inhibitor vs response) based on 4 individual patient sample sets (6-hour coculture). (E) Effects of CK1 inhibition (10 µM PF-670462) on the stroma-induced expression of CCL3 (i) and CCL4 (ii) are shown as a relative expression change normalized to the untreated unstimulated control for each data set (6-hour coculture; P = .0002 and .0034, N = 15, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). (F) Secreted chemokines CCL3 (i) and CCL4 (ii) were quantified by human-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in media harvested after 30 hours of incubation. No chemokines were detected in media harvested from mouse BM stromal cells or medium without cells (N = 3, P < .05, ratio paired Student t test).

CK1δ/ε inhibition blocks production of CCL3 and CCL4 by CLL cells in a coculture system. (A) Scheme of coculture experiments. (B) Expression of human CCL3 and CCL4 was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using human-specific primers in samples containing cocultured primary CLL and mouse stromal cells (N = 18). Relative change in the expression (with/without coculture) is shown. Columns represent median. (C-D) CK1 inhibitor treatment dose dependently (0.3-10 µM) inhibits the stroma-induced expression of CCL3/4 in CLL cells. EC50 values were estimated by nonlinear fit method (log inhibitor vs response) based on 4 individual patient sample sets (6-hour coculture). (E) Effects of CK1 inhibition (10 µM PF-670462) on the stroma-induced expression of CCL3 (i) and CCL4 (ii) are shown as a relative expression change normalized to the untreated unstimulated control for each data set (6-hour coculture; P = .0002 and .0034, N = 15, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). (F) Secreted chemokines CCL3 (i) and CCL4 (ii) were quantified by human-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in media harvested after 30 hours of incubation. No chemokines were detected in media harvested from mouse BM stromal cells or medium without cells (N = 3, P < .05, ratio paired Student t test).

CK1 inhibitor PF-670462 delays development of leukemia in the Eµ-TCL1 adoptive transfer (AT) model of CLL

Results of the in vitro assays, together with published data,27,28,33,34 indicated that PF-670462 is a compound suitable for further in vivo experiments. It is well tolerated and has good pharmacokinetic properties, reaching micromolar concentrations (effective in the in vitro assays) in plasma.27 We have decided to test this inhibitor in an AT model of murine Eµ-TCL1 leukemia, commonly used for preclinical testing of novel candidate drugs for CLL.12,35-37 The Gene Expression Omnibus database38,39 showed that csnk1e is expressed also in the case of leukemic B cells isolated from the Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mice23 (accession number GSE6092540 ) (supplemental Figure 4A), which suggests that these mice are a good model for analysis of CK1 inhibitors. To make sure that we effectively inhibit CK1ε in leukemic cells in vivo, we performed CK1ε autophosphorylation assay on primary PB WBCs isolated from PB of >12-month-old Eµ-TCL1 mice with progressed leukemia. This analysis showed that intraperitoneal injection of PF-670462 (10, 30, and 60 mg/kg) translates into a dose-dependent inhibition of CK1ε activity in vivo (Figure 4A). The in vivo effects were long lasting (up to 10 hours) as confirmed by the analysis of DVL3 phosphorylation, a sensitive marker of CK1ε activity (supplemental Figure 4B), in the colon samples of WT mice treated with 30 mg/kg dose (Figure 4B). Comparable effects were seen for intraperitoneal administration and oral administration (Figure 4B).

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 delays development of leukemia in the Eµ-TCL1 AT model of CLL. (A) In vivo CK1ε activity was assayed in primary PB WBCs isolated from Eµ-TCL1 mice with advanced spontaneous leukemia, which had been injected intraperitoneally by indicated doses of CK1 inhibitor. PB samples were taken 2 hours after the administration and processed by red blood cell (RBC) lysis and subsequent stimulation by 50 nM Calyculin A (10 minutes, 37°C), followed by cell lysis and western blotting analysis. (B) Activity of the CK1 inhibitor in vivo at time points 3 to 14 hours after administration was assessed by analysis of DVL3 phosphorylation status in the colon tissue of wild-type (WT) mice. The inhibitor was administered as 30 mg/kg (i.p., intraperitoneal; p.o., peroral = oral gavage), solvent only was used as a control (i.p.). DVL3 phosphorylation is a sensitive marker of CK1ε activity (see supplemental Figure 4B). (C) Typical disease progression in the AT leukemia model (N = 23). Day 0 = WT reference values (N = 16). Values are presented as means ± SEM. (Di) Scheme of experiment. (Dii) PF-670462 [21 days of treatment, administered by i.p. (N = 9) or by oral gavage (N = 6), control N = 8] reduces progression of CLL presented as lower WBC counts in the CK1 inhibitor treated group (unpaired Student t test, P = .0003). Merged data from 3 (i.p.) or 2 (oral gavage) independent experiments are presented. (Diii) The effect is evident also after 20 days treatment-free follow-up (P = .0435). Black lines indicate median. (E) Scheme of experiment analyzed in panels F through H. (F) Results of regular PB sampling of the experiment schematized in panel E. Values represent means ± SEM. Unpaired Student t test was used to compare CK1 inhibitor treated (N = 9) and control (N = 11) groups at indicated time points. (G) Spleen infiltration was measured by ultrasound after the end of inhibitor treatment (day 50; unpaired Student t test, P = .0183). Columns represent median value. (H) Mice were scored for overall survival (P = .027, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test). The x-axis presents the treatment-free period of the experiment, starting by day 50 (end of treatment).

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 delays development of leukemia in the Eµ-TCL1 AT model of CLL. (A) In vivo CK1ε activity was assayed in primary PB WBCs isolated from Eµ-TCL1 mice with advanced spontaneous leukemia, which had been injected intraperitoneally by indicated doses of CK1 inhibitor. PB samples were taken 2 hours after the administration and processed by red blood cell (RBC) lysis and subsequent stimulation by 50 nM Calyculin A (10 minutes, 37°C), followed by cell lysis and western blotting analysis. (B) Activity of the CK1 inhibitor in vivo at time points 3 to 14 hours after administration was assessed by analysis of DVL3 phosphorylation status in the colon tissue of wild-type (WT) mice. The inhibitor was administered as 30 mg/kg (i.p., intraperitoneal; p.o., peroral = oral gavage), solvent only was used as a control (i.p.). DVL3 phosphorylation is a sensitive marker of CK1ε activity (see supplemental Figure 4B). (C) Typical disease progression in the AT leukemia model (N = 23). Day 0 = WT reference values (N = 16). Values are presented as means ± SEM. (Di) Scheme of experiment. (Dii) PF-670462 [21 days of treatment, administered by i.p. (N = 9) or by oral gavage (N = 6), control N = 8] reduces progression of CLL presented as lower WBC counts in the CK1 inhibitor treated group (unpaired Student t test, P = .0003). Merged data from 3 (i.p.) or 2 (oral gavage) independent experiments are presented. (Diii) The effect is evident also after 20 days treatment-free follow-up (P = .0435). Black lines indicate median. (E) Scheme of experiment analyzed in panels F through H. (F) Results of regular PB sampling of the experiment schematized in panel E. Values represent means ± SEM. Unpaired Student t test was used to compare CK1 inhibitor treated (N = 9) and control (N = 11) groups at indicated time points. (G) Spleen infiltration was measured by ultrasound after the end of inhibitor treatment (day 50; unpaired Student t test, P = .0183). Columns represent median value. (H) Mice were scored for overall survival (P = .027, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test). The x-axis presents the treatment-free period of the experiment, starting by day 50 (end of treatment).

In AT experiments, leukemic cells gradually accumulate in PB (Figure 4C) and can be easily detected by flow cytometric analysis of PB samples because of a specific phenotype, CD5lowCD45Rlow12 (supplemental Figure 4C-D). In our initial AT experiment (schematized in Fig. 4Di), we treated mice with water dissolved PF-670462 CK1 inhibitor for 21 days with 60 mg/kg per 2 days (intraperitoneally) or by 30 mg/kg per day (oral gavage) and demonstrated that PF-670462 is able to reduce progression of CLL both immediately after the end of treatment (Figure 4Dii) and after 20 days of treatment-free follow-up (Figure 4Diii).

In the second experimental setup (Figure 4E) the treatment period was prolonged to 50 days and the drug was administered daily by oral gavage at 30 mg/kg/day. The disease progression was monitored weekly by PB sampling (starting at day 21) and spleen ultrasound (supplemental Figure 4E-G) and was scored for overall survival. In this setup, PF-670462–treated animals showed significantly lower WBC counts (Figure 4F) and lower leukemic cell counts (supplemental Figure 4H), leukemic cell proportion (supplemental Figure 4I), and spleen volume determined by ultrasound (Figure 4G) when compared with the control mice. Follow-up monitoring further showed that PF-670462–treated mice lived significantly longer compared with the control group (Figure 4H). However, after the end of the treatment (day 50), fast progression was observed resulting in a relatively small difference in the median overall survival (92 vs 85 days after cell transplantation). The spleen and liver size did not differ in the dead animals (supplemental Figure 4J), indicating that indeed the mice died when they reached the final stage of the disease. No obvious side effects of the treatment were detected.

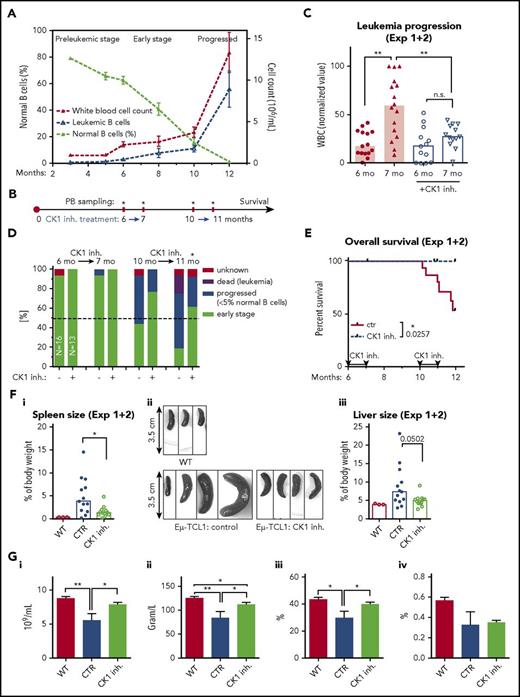

PF-670462 delays leukemic onset in the spontaneous Eµ-TCL1–induced murine CLL

To further assess the potential of PF-670462, we have analyzed its effects in the model of spontaneous Eµ-TCL1 leukemia (for typical progression, see Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 5A), which reflects closely the disease development in humans.41 In this model, leukemia appears spontaneously, in the presence of complete microenvironment and fully functional immune system. This enables to study the disease in its full complexity, taking into account the effects of an inhibitor on microenvironmental communication of leukemic cells.

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 delays leukemic onset in the Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mouse model of CLL. (A) Typical disease development in the model used in panels B through G. (B) Scheme of experiment. (C) Delay in the leukemia onset in the case of CK1 inhibitor treated group is presented as a difference in WBC counts. Only mice in the control group (N = 16) significantly progressed between months 6 and 7 (P = .0036, paired Student t test); CK1 inhibitor treated mice: N = 13, paired Student t test. The WBC counts were significantly different between groups after the treatment period (P = .0030, unpaired Student t test). Results from 2 independent experiments were merged together. WBC (normalized value): 0% = the lowest value in each data set; 100% = the highest value in each data set. Columns represent median. (D) Repeated treatment by the CK1 inhibitor at months 6 to 7 and 10 to 11 significantly delays progression of the disease, measured as a ratio of mice with highly progressed stage/dead mice vs mice with early stage of the disease in time (P = .0142, χ2 test). Dead of leukemia refers to mice that had enlarged spleen and had detectable progressed leukemia at the last PB sampling before death. (E) The inhibitor-treated mice lived significantly longer compared with the control group (N = 13 treated vs 16 control animals, experiments 1 and 2 merged; P = .0257, log-rank test). Overall survival is presented starting from the sixth month = start of the first treatment cycle. (F) Organ sizes were analyzed at the end of the experiment or at the time of death. WT, age-matched nontransgenic wild-type C57BL/6 littermates. (Fi) Spleens of the inhibitor treated mice were significantly smaller compared with the control group (N = 12 treated, 13 control and 3 WT animals, P = .0114, Mann-Whitney U test). (Fii) Examples of the spleens obtained by autopsy. (Fiii) A similar but not significant trend was noted in liver. Columns represent median. (G) PB analysis by hemoanalyzer was performed on 7 CK1 inhibitor treated mice and 4 control mice after the end of the survival analysis (experimental data set 1). The inhibitor treated mice were significantly less anemic, which is indicated by higher RBC counts (i) and hemoglobin (ii; HGB) or hematocrit (iii; HCT) levels compared with the control animals, close to WT littermates (N = 6). (iv) Plateletcrit (PCT) was not increased by treatment. Unpaired Student t test was used. Values are presented as mean ± SEM.

CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 delays leukemic onset in the Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mouse model of CLL. (A) Typical disease development in the model used in panels B through G. (B) Scheme of experiment. (C) Delay in the leukemia onset in the case of CK1 inhibitor treated group is presented as a difference in WBC counts. Only mice in the control group (N = 16) significantly progressed between months 6 and 7 (P = .0036, paired Student t test); CK1 inhibitor treated mice: N = 13, paired Student t test. The WBC counts were significantly different between groups after the treatment period (P = .0030, unpaired Student t test). Results from 2 independent experiments were merged together. WBC (normalized value): 0% = the lowest value in each data set; 100% = the highest value in each data set. Columns represent median. (D) Repeated treatment by the CK1 inhibitor at months 6 to 7 and 10 to 11 significantly delays progression of the disease, measured as a ratio of mice with highly progressed stage/dead mice vs mice with early stage of the disease in time (P = .0142, χ2 test). Dead of leukemia refers to mice that had enlarged spleen and had detectable progressed leukemia at the last PB sampling before death. (E) The inhibitor-treated mice lived significantly longer compared with the control group (N = 13 treated vs 16 control animals, experiments 1 and 2 merged; P = .0257, log-rank test). Overall survival is presented starting from the sixth month = start of the first treatment cycle. (F) Organ sizes were analyzed at the end of the experiment or at the time of death. WT, age-matched nontransgenic wild-type C57BL/6 littermates. (Fi) Spleens of the inhibitor treated mice were significantly smaller compared with the control group (N = 12 treated, 13 control and 3 WT animals, P = .0114, Mann-Whitney U test). (Fii) Examples of the spleens obtained by autopsy. (Fiii) A similar but not significant trend was noted in liver. Columns represent median. (G) PB analysis by hemoanalyzer was performed on 7 CK1 inhibitor treated mice and 4 control mice after the end of the survival analysis (experimental data set 1). The inhibitor treated mice were significantly less anemic, which is indicated by higher RBC counts (i) and hemoglobin (ii; HGB) or hematocrit (iii; HCT) levels compared with the control animals, close to WT littermates (N = 6). (iv) Plateletcrit (PCT) was not increased by treatment. Unpaired Student t test was used. Values are presented as mean ± SEM.

Using this model, we performed 2 30-day cycles of PF-670462 treatment (Figure 5B). The first treatment (PF-670462 at 60 mg/kg per 2 days, intraperitoneally) was administered for 30 days at the age of 6 months when animals showed early B-cell leukemia. In 2 independent experiments (in total N = 16 for control group and N = 13 for inhibitor-treated animals), the inhibitor-treated mice showed slower progression of the disease after the first cycle (Figure 5C; for individual experiments, see supplemental Figure 5B). The second treatment cycle was applied 3 months later, and mice were assessed by a simple staging system, which showed that PF-670462 was able to significantly slow down the disease progression (Figure 5D).

Most importantly, follow-up of these animals showed that PF-670462–treated mice survived significantly longer (Figure 5E). Surviving mice were euthanized, and their PB and organs were analyzed. We have observed significantly larger spleens in the control-treated mice compared with the animals receiving PF-670462 (Figure 5Fi-ii). A similar trend, albeit not significant, was observed also in the liver size (Figure 5Fiii). Hematological analysis of PB after the second treatment cycle showed significantly lower RBC counts, hematocrit, or hemoglobin levels in PB of the control mice compared with the inhibitor-treated mice (Figure 5G; supplemental Figure 5C). Moreover, these levels were comparable to the age-matched untreated wild-type C57BL/6 littermates, suggesting that PF-670462 can efficiently prevent onset of anemia, likely caused by BM infiltration by leukemic cells. Of note, the treatment with PF-670462 had no adverse effects on normal hematopoiesis in the age-matched wild-type animals (supplemental Figure 5C-D).

CK1 inhibition potentiates effects of ibrutinib in vitro and in vivo

The role of the BCR signaling pathway in CLL pathogenesis has been well described and is documented by the efficacy of BCR inhibitors, such as the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib, in CLL treatment.42 An existing rationale based on targeting the ROR1 receptor suggests that combined targeting of Wnt/PCP and BCR signaling in CLL can be beneficial.43,44 Therefore, we next addressed the question of whether CK1 inhibition further adds to the effects of ibrutinib when used in combination (Figure 6A). To rule out the possibility that PF-670462 and ibrutinib cross-react (ie, PF-670462 inhibits the BCR pathway or ibrutinib inhibits CK1), we have performed analysis of signaling activity in primary CLL cells. CK1ε autophosphorylation assay (N = 3; Figure 6B) showed that ibrutinib has no effect on CK1ε activity, and BCR-activation assay triggered by anti-IgM (N = 4; Figure 6C) showed that PF-670462 in the tested conditions does not affect the activity of the BCR signaling pathway measured as the phosphorylation of BTK, PLCγ2, SYK, or ERK1/2 (for quantification, see Figure 6D-E and supplemental Figure 6A-C).

Combinatory effects of CK1 inhibition by PF-670462 and ibrutinib. (A) Scheme of the inhibitors’ mode of action. Common processes in CLL cells can be targeted by inhibition of either BCR or CK1-dependent signaling. (B) Inhibitory effects of PF-670462 and ibrutinib on CK1ε activity in primary CLL cells were tested via CK1 autophosphorylation assay. Representative western blotting analysis is presented. PF-670462 inhibits almost completely CK1ε activity at a 10-µM dose. (C) Inhibitory effects of PF-670462 and ibrutinib on BCR pathway activity (triggered by anti–immunoglobulin M [IgM], 4 minutes). Representative western blotting analysis is presented. Ibrutinib almost completely blocks activity of BTK in primary CLL cells already at 0.1-µM dose (determined by autophosphorylation of BTK at Y223 and phosphorylation of its substrate PLCγ2 at Y1217) and at higher concentrations also affects activity of the other pathway components, such as SYK (phosphorylation of Y525/526) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2). (D-E) Quantification of the western blotting analysis performed in panels B and C; further quantification is presented in supplemental Figure 6A-C. Columns represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). (F) Combination of ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor treatment leads to significantly stronger inhibition of cell chemotaxis toward both CXCL12 (N = 5, P = .0156; ratio-paired Student t test) and CCL19 (N = 11, P = .0010; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). Data were normalized toward the condition treated by both ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor. Asterisks represent results of the paired-tests of raw MIs from supplemental Figure 6D-E. Columns represent mean ± SEM. (G) Combination of ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor treatments showed synergistic effects on chemotaxis of primary CLL cells toward CCL19 chemokine in a transwell assay (N = 3). Inhibitory effects are presented as a fold change of control, concentration range of 0.03 to 1 µM was tested in the case of ibrutinib and 0.03 to 10 µM in the case of CK1 inhibitor. Mean ± SD is presented. Corresponding isobolographic analysis with detailed description is presented in supplemental Figure 6I; data for 3 individual CLL patients are presented in supplemental Figure 6Ji-iii. (H) AT experiment was performed as described in Figure 4. Inhibitor treatment lasted until day 42, when control animals reached highly progressed stage of the disease, while still no leukemia was detected in the animals treated by CK1 inhibitor/ibrutinib combination. Significant difference between ibrutinib only and ibrutinib/CK1 inhibitor combination treatment was detected (ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test), and both single treatments were significantly different from control (N = 8 animals/group, 6 in the control group). Dashed vertical line marks the day of spleen size analysis by ultrasound. Mean ± SD is presented. (I) Spleen volume as determined by ultrasound at day 38 (N = 4/4/4/6/4). Gray lines represent median; dashed line highlights WT spleen size. All treatments were significantly different from the control group (1-way ANOVA, P < .0001). (J) Follow-up and overall survival after the end of treatments at day 42. Ibrutinib-treated animals show shorter overall survival (median 74.5 days) compared with the animals treated by both inhibitors (89 days, P = .001) or CK1 inhibitor alone (median not defined, P < .0001) and control group (85 days, P = .0083). Results of survival analysis are also significant for single CK1 inhibitor treatment vs control group (P = .0001, all log-rank test).

Combinatory effects of CK1 inhibition by PF-670462 and ibrutinib. (A) Scheme of the inhibitors’ mode of action. Common processes in CLL cells can be targeted by inhibition of either BCR or CK1-dependent signaling. (B) Inhibitory effects of PF-670462 and ibrutinib on CK1ε activity in primary CLL cells were tested via CK1 autophosphorylation assay. Representative western blotting analysis is presented. PF-670462 inhibits almost completely CK1ε activity at a 10-µM dose. (C) Inhibitory effects of PF-670462 and ibrutinib on BCR pathway activity (triggered by anti–immunoglobulin M [IgM], 4 minutes). Representative western blotting analysis is presented. Ibrutinib almost completely blocks activity of BTK in primary CLL cells already at 0.1-µM dose (determined by autophosphorylation of BTK at Y223 and phosphorylation of its substrate PLCγ2 at Y1217) and at higher concentrations also affects activity of the other pathway components, such as SYK (phosphorylation of Y525/526) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2). (D-E) Quantification of the western blotting analysis performed in panels B and C; further quantification is presented in supplemental Figure 6A-C. Columns represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). (F) Combination of ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor treatment leads to significantly stronger inhibition of cell chemotaxis toward both CXCL12 (N = 5, P = .0156; ratio-paired Student t test) and CCL19 (N = 11, P = .0010; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). Data were normalized toward the condition treated by both ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor. Asterisks represent results of the paired-tests of raw MIs from supplemental Figure 6D-E. Columns represent mean ± SEM. (G) Combination of ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor treatments showed synergistic effects on chemotaxis of primary CLL cells toward CCL19 chemokine in a transwell assay (N = 3). Inhibitory effects are presented as a fold change of control, concentration range of 0.03 to 1 µM was tested in the case of ibrutinib and 0.03 to 10 µM in the case of CK1 inhibitor. Mean ± SD is presented. Corresponding isobolographic analysis with detailed description is presented in supplemental Figure 6I; data for 3 individual CLL patients are presented in supplemental Figure 6Ji-iii. (H) AT experiment was performed as described in Figure 4. Inhibitor treatment lasted until day 42, when control animals reached highly progressed stage of the disease, while still no leukemia was detected in the animals treated by CK1 inhibitor/ibrutinib combination. Significant difference between ibrutinib only and ibrutinib/CK1 inhibitor combination treatment was detected (ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test), and both single treatments were significantly different from control (N = 8 animals/group, 6 in the control group). Dashed vertical line marks the day of spleen size analysis by ultrasound. Mean ± SD is presented. (I) Spleen volume as determined by ultrasound at day 38 (N = 4/4/4/6/4). Gray lines represent median; dashed line highlights WT spleen size. All treatments were significantly different from the control group (1-way ANOVA, P < .0001). (J) Follow-up and overall survival after the end of treatments at day 42. Ibrutinib-treated animals show shorter overall survival (median 74.5 days) compared with the animals treated by both inhibitors (89 days, P = .001) or CK1 inhibitor alone (median not defined, P < .0001) and control group (85 days, P = .0083). Results of survival analysis are also significant for single CK1 inhibitor treatment vs control group (P = .0001, all log-rank test).

Both PF-670462 (this study) and ibrutinib were described to inhibit chemotaxis of primary CLL cells.7,45 With this in mind, we analyzed chemotactic capacity of primary CLL cells cotreated with PF-670462 and 0.1 μM ibrutinib (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 6D-F). This dose of ibrutinib showed basically complete BTK inhibition (Figure 6C) without direct toxicity in the 6-hour treatment as a single agent (supplemental Figure 6G) or in combination (supplemental Figure 6F,H). In the case of a single-agent treatment, we observed significant decrease in the chemotaxis toward both CCL19 and CXCL12 after CK1 inhibition; ibrutinib treatment reduced chemotaxis toward CCL19 only (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 6D-E). Importantly, the combination of CK1 inhibitor and ibrutinib was the most effective. We further explored nature of these combinatory effects using isobolographic analysis based on CCL19-induced transwell migration data (N = 3) with 0.03 to 1 µM dose response for ibrutinib and 0.03 to 10 µM for PF-670462. Results confirmed that the effect on migration is synergistic (Figure 6G; supplemental Figure 6I) despite some variability among patients (supplemental Figure 6J).

These data suggest that targeting both Wnt/PCP and BCR pathways via CK1 inhibition might be in principle beneficial as suggested recently by others.43,44 In order to test this assumption, we performed another in vivo AT experiment as described in Figure 4. In this case, the mice were divided into 5 groups: 8 mice were not transplanted and served as a reference; all the other mice were transplanted by leukemic cells and treated with CK1 inhibitor, ibrutinib, or combination (8 mice each group) or solvent as a control (6 mice). All drugs were dissolved in kolliphor in order to administer the same solvent. Mice were treated for 42 days with 30 mg/kg per day (by oral gavage, both compounds), and their PB was regularly sampled (Figure 6H). On the day 38, ultrasound measurement was performed (Figure 6I). Both analyses confirmed previous findings about significant effects of CK1 inhibitor and ibrutinib36,46 as a single treatment; however, the combination showed to be most effective and essentially stopped accumulation of leukemic cells in PB (Figure 6H) and spleen (Figure 6I). Interestingly, follow-up analysis after treatment cessation showed rapid progression of ibrutinib-treated animals; this ibrutinib effect was significantly slowed down by PF-670462 cotreatment (Figure 6J). PF-670462–only treated mice survived the longest (Figure 6J), which shows that PF-670462 brings significant benefits both as a single agent and in combination with ibrutinib. In summary, these results demonstrate that CK1 inhibition represents a viable treatment strategy that can be efficiently combined with BCR inhibitors.

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence that CK1δ/ε inhibition can slow down development of CLL in Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mice (AT and spontaneous disease development) and that the CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 can improve overall survival in this mouse model. Even though there are numerous links of CK1δ/ε isoforms to cancer development,47-51 only a limited number of studies describing CK1 inhibition as an option for cancer therapy exist; the published studies use mostly IC261 compound to block cancer cell proliferation,52-55 an effect that is likely to be observed because of the off-target effects of this inhibitor.56 Our study is thus the first one that shows the potential of specific CK1δ/ε inhibition in cancer treatment using a spontaneous disease in vivo model and demonstrates its therapeutic effects at doses that do not cause any apparent toxicity.

Our study further expands the earlier observations that CK1δ/ε inhibitors can block chemotaxis and transendothelial migration of primary CLL cells in vitro7,8 and disrupt CLL cell homing to lymphoid organs in vivo.7 We show that CK1δ/ε inhibition blocks production of CCL3 and CCL4 by CLL cells and also blocks CLL migration in response to multiple microenvironmental stimuli. These diverse activities possibly converge on the requirement of CK1 activity for establishment of cell polarity and asymmetric localization of Wnt/PCP components, namely VANGL2, as was shown earlier using live imaging in MEC-1 cells.8 Our data not only highlight the importance of CK1-controlled processes in CLL pathogenesis, but also identify CK1δ/ε inhibitors as candidate drugs for CLL. So far, only anti-ROR1 antibodies have been studied in this context, and especially UC-96157,58 showed highly promising effects. The effects of ROR1 inhibition were further described by others and carry high potential in the clinical applications in CLL as well as other ROR1-driven malignancies.11,12,57,59-62 CK1δ/ε inhibition represents a complementary, small-molecule–based approach to anti-ROR1 antibodies and further widens the treatment options based on targeting of Wnt/PCP signaling.

Despite the undeniable benefits of recently approved compounds, mainly the BCR inhibitors ibrutinib and idelalisib63 and Bcl2 inhibitor venetoclax,64 the clinical trials have identified multiple side effects of these inhibitors64,65 and a risk of acquired resistance in the case of BTK inhibitors.66 In addition, the treatments are not curative and need to be ideally indefinite. All these facts argue for further exploitation of novel therapeutic targets. This involves validation of the therapeutic potential of CK1δ/ε inhibitors, which were so far tested and well tolerated in preclinical in vivo studies.27,28,33,34,67 Interestingly, CK1ε was shown to be targeted by a PI3Kδ inhibitor TGR-1202 (umbralisib),68 currently in phase 3 clinical trial, which shows good activity and differs from the other PI3Kδ inhibitors by a better safety profile.69,70 It must be further explored in future whether this is because of the dual PI3Kδ and CK1ε activity of TGR-1202.

To verify the beneficial effects of CK1δ/ε inhibition in a combination therapy, a strategy commonly applied in CLL,71 we have explored the effects of a combined treatment by CK1δ/ε and BTK inhibitors. This combination showed to be synergistic in vitro and beneficial also in vivo. PF-670462 slowed down the rapid disease progression after ibrutinib withdrawal that appeared in line with the fact that ibrutinib cannot completely eradicate the disease in mice36,46 and CLL patients.72 Even though we could not cure the disease in the mouse model completely using the current experimental setup, we hypothesize that a careful optimization of the conditions used (eg, differences in a solvent, water vs kolliphor; compare Figures 4H and 6J) and better understanding of the compound pharmacokinetics may deliver even stronger effects. This, together with testing of further treatment combinations, is, however, out of the scope of the current study.

In summary, we have identified inhibition of CK1δ/ε as a novel approach for interference with the network of microenvironment-controlled pathways. Overall, the evidence presented in this manuscript demonstrates that CK1δ/ε should be considered as a valid therapeutic target in CLL and potentially also in other CK1-driven malignancies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Department of Internal Medicine–Hematology and Oncology, University Hospital Brno for the help with collecting biological samples from CLL patients, and Carlo Croce (The Ohio State University College of Medicine) for providing us with the Eµ-TCL1 mice.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (15-29793A, 16-34152A); Masaryk University/Internal projects of Technology Transfer Office (MUNI/31/53609/2016); the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under the project CEITEC 2020 (LQ1601); the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic–Conceptual Development of Research Organization (FNBr, 65269705); the European Commission (WntsApp Marie Curie Initial Training Network); the Ministry of Agriculture Institutional (grant RO0517); and the Czech Science Foundation (grant 16-24043J). A.E.’s work on CLL is supported by Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung grants p26719 and I1299 (FOR2036). P.J.’s work on the manuscript was supported by Masaryk University Grant Agency project MUNI/E/0102/2017.

Authorship

Contribution: V.B., P.J., J.V., J.K., and T.N. were responsible for experimental design and data analysis; P.J., V.B., and J.V. wrote the manuscript; J.V., J.K., M.D., H.S., T.N., and P.J. worked with the animals; T.R., L.B., T.N., P.J., L.S., M.G., and O.V.B. performed in vitro experiments/analysis of samples from mice; K.V., J.V., and Z.H. performed ultrasound and other special analysis; P.O. performed statistical analysis; A.E., S. Pavlova, K.P., and L.P. provided crucial material and know-how; and V.B. and S. Pospisilova supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.B., S. Pavlova, K.P., and S. Pospisilova are listed as inventors in the patent application “WO 2014023271 A1: Casein kinase 1 inhibitors for the treatment of b-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia.” The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Vitezslav Bryja, Institute of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Kotlarska 2, 611 37 Brno, Czech Republic; e-mail: bryja@sci.muni.cz.

References

Author notes

J.V. and J.K. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. CK1ε is upregulated in CLL, and its activity is inhibited by PF-670462 inhibitor at low micromolar concentration. (A) CSNK1E expression (probe 38019_at); microarray data obtained from the Oncomine database24 (‘Basso Lymphoma’ data set25). CLL PB samples (N = 34) compared with nonmalignant PB B-cell populations: naïve (N = 5) and memory (N = 5) (1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], P < .0001). Black lines represent median. (B) Protein levels in primary CLL samples (N = 6) and healthy controls (buffy coats, N = 3) were analyzed by western blotting (i). Quantification of detected CK1ε levels performed by ImageJ software (P = .0310, unpaired Student t test) (ii). CK1ε protein level in MEC-1 cell line in comparison with primary CLL and healthy control samples (iii). Activity of CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 was tested in a transwell migration assay (6 hours, CCL19-induced chemotaxis) using MEC-1 cell line (C; N = 3) and 4 freshly isolated primary CLL samples (D). Relative migration index (left y-axis, red) represents ratio between cells migrated toward chemokine in the inhibitor-treated and control conditions. Viability (right y-axis, blue) was tested in parallel by tetramethylrhodamine staining. Vertical dashed lines represent EC50 values. Symbols represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (E) Activity of CK1ε after PF-670462/dimethyl sulfoxide treatment (2 hours) in primary CLL cells stimulated by 50 nM Calyculin A (1 hour); upper band represents autophosphorylated form (PS-CK1ε), which is not present in an unstimulated sample and is lost dose-dependently upon CK1ε inhibition with maximum effect at 10 µM concentration. Representative result is presented (N = 3).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/11/10.1182_blood-2017-05-786947/4/m_blood786947f1.jpeg?Expires=1769085163&Signature=m1oyMTxTRt4ZBsNFxHOY7q9lryuoMdbDNiLD-mfeA9XEkc54LyE~tde5SQEItG~6WgQ7FyrMw~clwyRfM5aQCeiV4pNZsG~nIYht3c4FuNkACaPlt1Ob5o8xr2d3wYfAfMshLvF27MVW2q~Aw7z1otnBwErlPaUnPzXqnMVau9vnthZlR9~UCevO95OPartR8NCghHhhZwe9v8Gbkoh7w4R9qad9QTGu34cOk4eRkIrNEzdSYcy00rkKSOO957kpfmXOegnzD6SA-RmRx~ykqY2TLBB5IjJFukwEuWG0JS3KjwNfSQV-fbQf9sqAYVOOnRt--w8t~YOfxMmObGpFYw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. CK1δ/ε inhibitor PF-670462 delays development of leukemia in the Eµ-TCL1 AT model of CLL. (A) In vivo CK1ε activity was assayed in primary PB WBCs isolated from Eµ-TCL1 mice with advanced spontaneous leukemia, which had been injected intraperitoneally by indicated doses of CK1 inhibitor. PB samples were taken 2 hours after the administration and processed by red blood cell (RBC) lysis and subsequent stimulation by 50 nM Calyculin A (10 minutes, 37°C), followed by cell lysis and western blotting analysis. (B) Activity of the CK1 inhibitor in vivo at time points 3 to 14 hours after administration was assessed by analysis of DVL3 phosphorylation status in the colon tissue of wild-type (WT) mice. The inhibitor was administered as 30 mg/kg (i.p., intraperitoneal; p.o., peroral = oral gavage), solvent only was used as a control (i.p.). DVL3 phosphorylation is a sensitive marker of CK1ε activity (see supplemental Figure 4B). (C) Typical disease progression in the AT leukemia model (N = 23). Day 0 = WT reference values (N = 16). Values are presented as means ± SEM. (Di) Scheme of experiment. (Dii) PF-670462 [21 days of treatment, administered by i.p. (N = 9) or by oral gavage (N = 6), control N = 8] reduces progression of CLL presented as lower WBC counts in the CK1 inhibitor treated group (unpaired Student t test, P = .0003). Merged data from 3 (i.p.) or 2 (oral gavage) independent experiments are presented. (Diii) The effect is evident also after 20 days treatment-free follow-up (P = .0435). Black lines indicate median. (E) Scheme of experiment analyzed in panels F through H. (F) Results of regular PB sampling of the experiment schematized in panel E. Values represent means ± SEM. Unpaired Student t test was used to compare CK1 inhibitor treated (N = 9) and control (N = 11) groups at indicated time points. (G) Spleen infiltration was measured by ultrasound after the end of inhibitor treatment (day 50; unpaired Student t test, P = .0183). Columns represent median value. (H) Mice were scored for overall survival (P = .027, Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test). The x-axis presents the treatment-free period of the experiment, starting by day 50 (end of treatment).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/11/10.1182_blood-2017-05-786947/4/m_blood786947f4.jpeg?Expires=1769085163&Signature=G2ISKJiD80PG3X38SdlVOoM0HpoEwF~AZ-G6unyEH0NenQkfGUZEBTpFT3v7Tn9emBrr9n4xUqibPPoPawDfir0wUZIjmcKAVlUw4tdmo5FUAo3xSSDQZYzMhYdP0rVMbqa6c6-R0QhbZ2pureSdnkKnD4Xiz91huNS3m7DtmFBNFemj6uIL9qVzxo2zDbQ9XBWCF8XISuaMm2QnJZIKiwI3ueZRThmsly5EM7MtCoxPpPT~tQcGWG7GwnmZTO~5V03z4ShxIRyYILwEDVXXXbHZuRZjJPG~RyFnz-J0eDfnqUjiuBAc-Ya-O16gDsmJE25OFgZybWQP8A3nuvBxdw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 6. Combinatory effects of CK1 inhibition by PF-670462 and ibrutinib. (A) Scheme of the inhibitors’ mode of action. Common processes in CLL cells can be targeted by inhibition of either BCR or CK1-dependent signaling. (B) Inhibitory effects of PF-670462 and ibrutinib on CK1ε activity in primary CLL cells were tested via CK1 autophosphorylation assay. Representative western blotting analysis is presented. PF-670462 inhibits almost completely CK1ε activity at a 10-µM dose. (C) Inhibitory effects of PF-670462 and ibrutinib on BCR pathway activity (triggered by anti–immunoglobulin M [IgM], 4 minutes). Representative western blotting analysis is presented. Ibrutinib almost completely blocks activity of BTK in primary CLL cells already at 0.1-µM dose (determined by autophosphorylation of BTK at Y223 and phosphorylation of its substrate PLCγ2 at Y1217) and at higher concentrations also affects activity of the other pathway components, such as SYK (phosphorylation of Y525/526) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2). (D-E) Quantification of the western blotting analysis performed in panels B and C; further quantification is presented in supplemental Figure 6A-C. Columns represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). (F) Combination of ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor treatment leads to significantly stronger inhibition of cell chemotaxis toward both CXCL12 (N = 5, P = .0156; ratio-paired Student t test) and CCL19 (N = 11, P = .0010; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test). Data were normalized toward the condition treated by both ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor. Asterisks represent results of the paired-tests of raw MIs from supplemental Figure 6D-E. Columns represent mean ± SEM. (G) Combination of ibrutinib and CK1 inhibitor treatments showed synergistic effects on chemotaxis of primary CLL cells toward CCL19 chemokine in a transwell assay (N = 3). Inhibitory effects are presented as a fold change of control, concentration range of 0.03 to 1 µM was tested in the case of ibrutinib and 0.03 to 10 µM in the case of CK1 inhibitor. Mean ± SD is presented. Corresponding isobolographic analysis with detailed description is presented in supplemental Figure 6I; data for 3 individual CLL patients are presented in supplemental Figure 6Ji-iii. (H) AT experiment was performed as described in Figure 4. Inhibitor treatment lasted until day 42, when control animals reached highly progressed stage of the disease, while still no leukemia was detected in the animals treated by CK1 inhibitor/ibrutinib combination. Significant difference between ibrutinib only and ibrutinib/CK1 inhibitor combination treatment was detected (ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test), and both single treatments were significantly different from control (N = 8 animals/group, 6 in the control group). Dashed vertical line marks the day of spleen size analysis by ultrasound. Mean ± SD is presented. (I) Spleen volume as determined by ultrasound at day 38 (N = 4/4/4/6/4). Gray lines represent median; dashed line highlights WT spleen size. All treatments were significantly different from the control group (1-way ANOVA, P < .0001). (J) Follow-up and overall survival after the end of treatments at day 42. Ibrutinib-treated animals show shorter overall survival (median 74.5 days) compared with the animals treated by both inhibitors (89 days, P = .001) or CK1 inhibitor alone (median not defined, P < .0001) and control group (85 days, P = .0083). Results of survival analysis are also significant for single CK1 inhibitor treatment vs control group (P = .0001, all log-rank test).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/131/11/10.1182_blood-2017-05-786947/4/m_blood786947f6.jpeg?Expires=1769085163&Signature=YTifOUgnRCGcxDcbMvH5JkmSy1EHWeW0h4vl5vi8SiDdGAHBYgvgHRMUMzUqOCfAya04p9drKQLPM59ihXPgLeAQanbLIy9z8MZ1ufuvAJ2~f7vvpYcU3~hprxwdKSAnwWoXCaS0e6CscIH584u7sA-6jJAxyxpPca-~jEsvoKhfq~bTm4i3BpHzx-7KNYxwWDwWEWBdpPRQ3rMPJJDELOhlfL2w3ThkQh~hbjtq3daaI4K86Mir~1v4u0CLGxyQGsjk7gNlWdgmFD6S156zUZgKPUzeEJfpAsMY7249tY0kqpYT7mSbCMoutjPwIgczbFLfdcedgW6ct3DEfhYpQA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal