Coutre et al conducted a multicenter phase 2 study on the use of venetoclax for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) progressing during or after treatment with idelalisib or ibrutinib. In this issue of Blood, they report the results in 36 patients who received idelalisib as their last therapy.1 Treatment with venetoclax resulted in a high objective response rate (67%) and an estimated progression-free survival of 79% at 12 months, while reporting only moderate toxicity.

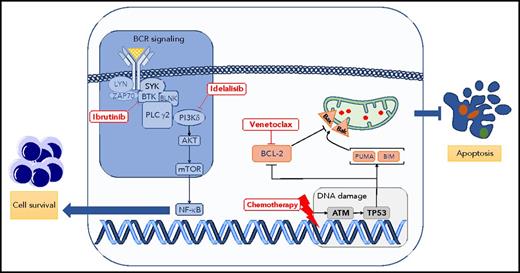

Critical signaling pathways for survival and apoptosis in CLL. The BCR signaling pathway is constitutively activated and leads to several effects, including proliferation, maturation, and migration in CLL. This pathway is pharmacologically blocked by several inhibitors, such as ibrutinib (Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor) or idelalisib (PI3K isoform δ inhibitor). At the same time, CLL cells are skewed toward a phenotype evading apoptosis. Apoptosis can be triggered by inducing DNA damage (purine analogs, alkylating agents) or by blocking BCL-2 protein using the BH3 mimetic drug venetoclax. Bak, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer; Bax, bcl-2–like protein 4; BIM, B-cell lymphoma 2 interacting mediator of cell death; BLNK, B cell linker; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; PLC, phospholipase C; PUMA, p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase.

Critical signaling pathways for survival and apoptosis in CLL. The BCR signaling pathway is constitutively activated and leads to several effects, including proliferation, maturation, and migration in CLL. This pathway is pharmacologically blocked by several inhibitors, such as ibrutinib (Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor) or idelalisib (PI3K isoform δ inhibitor). At the same time, CLL cells are skewed toward a phenotype evading apoptosis. Apoptosis can be triggered by inducing DNA damage (purine analogs, alkylating agents) or by blocking BCL-2 protein using the BH3 mimetic drug venetoclax. Bak, Bcl-2 homologous antagonist killer; Bax, bcl-2–like protein 4; BIM, B-cell lymphoma 2 interacting mediator of cell death; BLNK, B cell linker; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; PLC, phospholipase C; PUMA, p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase.

Because of the advent of different therapies targeting critical and divergent biological processes of CLL, we have witnessed in the last 5 years impressive progress in the treatment of this most commonly occurring chronic leukemia in the United States and Europe.2-5 The B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway, critical to promoting cell proliferation and survival in CLL,6 is targeted by ibrutinib and idelalisib, 2 of several inhibitors currently licensed for the treatment of CLL. Conversely, the BCL-2 protein members that tightly regulate the apoptotic process are, in CLL, skewed toward a phenotype aimed to evade apoptosis.7 Blocking BCL-2 protein function by the BH3 mimetic drug venetoclax leads to apoptosis of CLL cells and excellent control of the disease (see figure).5

Why was this clinical trial performed? Idelalisib, an oral phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) isoform δ selective inhibitor, has been approved in combination with rituximab or ofatumumab for the treatment of relapsed/refractory CLL.3,8 In spite of its significant activity, one-third of patients progressed while on treatment, whereas ∼50% discontinued idelalisib owing to adverse events, with the survival after discontinuation being less than 3 months.9 The ideal salvage therapy for CLL patients failing idelalisib therapy has not been defined. Venetoclax seems a natural choice, because of its different mechanism of action.

What are the lessons learned from this study? Venetoclax showed promising activity after idelalisib failure in patients with CLL with adverse prognostic features; namely, 88% of cases had unmutated IGHV genes, or ∼30% had TP53 gene disruption. Notably, with the use of venetoclax it was reported that a substantial number (40%) of patients had undetectable minimal residual disease. All of this activity translated to a prolonged progression-free survival (Coutre et al’s Figure 2). Remarkably, discontinuing venetoclax was primarily due to progression of the disease, whereas toxicity was tolerable and mainly hematological. The study has significant limitations, among them the relatively small number of patients reported and short follow-up. Unfortunately, biological and further genetic analyses in this trial were somewhat limited, preventing identification of markers predicting response to venetoclax. Finally, it would have been desirable to report in 1 article the results of venetoclax in patients relapsing to ibrutinib10 to allow for a direct comparison of treatment efficacy and side effects of venetoclax after BCR inhibitor therapy.

In summary, salvage therapy with venetoclax following idelalisib therapy of CLL has emerged as an excellent option and deserves further study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.B. received research support from Roche, Gilead, Janssen, Celgene, Novartis, AbbVie, and Takeda; and honoraria from Roche, Gilead, Janssen, Celgene, AbbVie, and Takeda. M.H. received research support from Roche, Gilead, Mundipharma, Janssen, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, and AbbVie; and honoraria from Roche, Gilead, Mundipharma, Janssen, Celgene, Pharmacyclics, and AbbVie.