Abstract

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a rare, clinically aggressive lymphoma entity characterized by an almost exclusive growth of large cells within the lumen of all sized blood vessels. The reasons for this peculiar localization of neoplastic cells are only partially understood. Clinically, in its classical variant, IVLBCL presents with many nonspecific signs and symptoms such as fever of unknown origin and involvement of the central nervous system and skin. Cases, which show disease limited to the skin, following extensive staging workup, are called cutaneous variants and show a better prognosis. In addition, a hemophagocytic variant associated with hemophagocytic syndrome and often with hepatosplenic involvement and cytopenia has been described. The classical and hemophagocytic variants are present mainly in western or Asian countries, respectively, although exceptions have been increasingly reported in both geographical areas. The cutaneous variant is mostly observed in western countries. Staging of IVLBCL is difficult and still not satisfactory. The often poor prognosis of this type of lymphoma has been substantially improved by immunochemotherapy, in particular with rituximab. Despite improved outcome, a significant proportion of patients relapse, in particular those with central nervous system manifestations. This review focuses on histopathological features, pathogenetic elements, presenting symptoms, clinical variants, disease progression, prognostic factors, therapeutic management, and the outcome of IVLBCL.

Introduction

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL), whose B-cell origin was demonstrated ∼30 years ago,1 is a rare lymphoma entity characterized by the predominant, if not exclusive, growth of large cells within the lumen of different-sized blood vessels.2 Behind this relatively intuitive definition, however, many unclear aspects persist. Even though the fundamental peculiarity of the localization of neoplastic lymphocytes is within vessels, the occurrence of IVLBCL cells in routine peripheral blood smears does not occur in most instances (90%-95% of cases) in spite of careful morphological examination.3 Another limiting factor is that available data on this rare disease mostly rely on single or limited case reports. This bias implies that relatively few large studies have been published, making it difficult to draw conclusions. On the other hand, although the vast majority of patients with IVLBCL were diagnosed in the past at autopsy,4 this trend has been reverted; recent data report an ante mortem diagnosis in ∼80% of patients.5 This situation implies that the natural history of IVLBCL has been substantially modified by improvements in early clinical recognition and therapy. Rare forms with T-cell or natural killer cell phenotype have been described, but are not considered part of this work and will not herein be analyzed.6

This review focuses on histopathological characteristics, pathogenetic features, presenting symptoms, clinical variants, disease progression, prognostic factors, therapeutic management, and outcome of IVLBCL diagnosed across geographical areas, mostly western and eastern countries.

Histopathological features

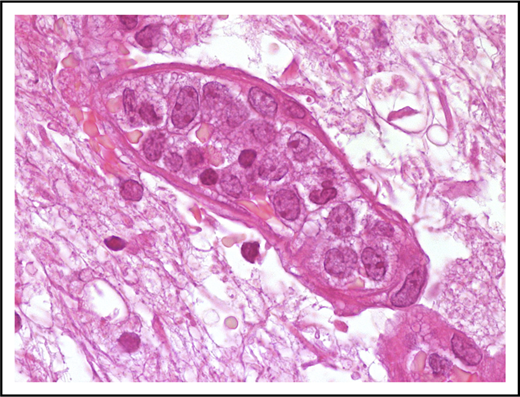

Neoplastic cells are in most instances large with high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and scant cytoplasm (Figure 1). Nuclear outline is usually smooth, less often with irregular contour.

Morphological features of IVLBCL. A blood vessel lumen filled mainly with large B neoplastic lymphocytes, mostly resembling centroblasts. Hematoxylin-and-eosin stain; original magnification ×1000.

Morphological features of IVLBCL. A blood vessel lumen filled mainly with large B neoplastic lymphocytes, mostly resembling centroblasts. Hematoxylin-and-eosin stain; original magnification ×1000.

Isolated cases characterized by smaller cells with irregular nuclear profiles have been reported.3 The nucleolus may be single and prominent or multiple nucleoli may be readily recognizable. IVLBCL, therefore, shows a morphological spectrum ranging from centroblasts to immunoblasts/plasmablasts,3,7,8 including rare forms with anaplastic morphology.9 The blood vessel lumen is not only certainly the diseases’ vehicle but also its site of active replication, as confirmed by the presence of mitotic figures and the high proliferative index highlighted by Ki-67 immunostaining. With the theoretical exception of major vessels, almost all blood vessels could be involved by IVLBCL.3 Different growth patterns may be recognized in this type of lymphoma and usually coexist in the same sample or patient. In the “discohesive” pattern, IVLBCL cells are preferentially within the central portion of the blood vessels and exhibit a free-floating appearance, whereas in the “cohesive” pattern neoplastic cells almost completely fill the lumen and assessment of the vascular structure tends to be difficult. The less frequent pattern is named “marginating” because tumor cells preferentially adhere to endothelia leaving the central portion of the lumen free.10 Cases of IVLBCL associated with hemophagocytosis are accompanied by nonneoplastic histiocytes filled with red cells or mononuclear cells. Cells with phagocytic activity may be readily visible in peripheral blood smears (see “Hemophagocytic syndrome-associated variant”).

In a limited number of cases, IVLBCL may be diagnosed, preceded, or followed by various types of lymphomas: small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and diffuse large cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified.11 A recent report showed distinct clonal origin in a patient with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and subsequent IVLBCL.12 However, the relationship between “solid” lymphomas and IVLBCL has not yet been characterized and therefore deserves to be further investigated.

Immunophenotype

IVLBCL cells display the immunophenotype of mature peripheral B cells. Strong and constant CD20 expression is almost the rule, a feature critical for its current therapeutic implications. Exceptionally, CD20− cases have been reported: in these situations, alternative B-cell markers like CD79a and/or Pax-5 facilitate correct diagnosis.13 The few relatively large reports available reveal the immunophenotypical heterogeneity of this lymphoma. In western countries and Japan, CD10 and bcl-6 positivity is found in 13% to 22% and 22% to 26% of cases, respectively.14,15 Based on the Hans algorithm,16 75% to 80% of these cases show a non–germinal center phenotype with Irf4/Mum1 expression,15 even though gene-expression profiling studies have not been performed in these tumors. Considering these characteristics, it should be pointed out that the immunophenotype of IVLBCL may in some cases, but not always, overlap that of DLBCL not otherwise specified. For instance, although CD5 is detected in only ∼5% of DLBCL cases,17 this marker has been reported in 22% to 38% of patients with IVLBCL.5,13,14 Furthermore, CD5 is coexpressed with bcl-6 in ∼20% of IVLBCL patients.13 Antiapoptotic proteins, mainly bcl-2,14,15 though also galectin-3 (anecdotally reported),18 are positive in IVLBCL. Unexpected additional expression of molecules such as myeloperoxidase,19 cytokeratin,20 and prostatic acid phosphatase21 deserves to be confirmed by studies in a larger number of patients. Taking into account these data, there is a need for further studies that aim to better elucidate the ontogeny of this rare lymphoma.

Molecular biology and cytogenetics

Earlier studies using Southern blot22 and later investigations based on polymerase chain reaction23 have demonstrated clonal rearrangements of immunoglobulin genes in IVLBCL. In addition, small studies reported the common occurrence of somatic hypermutation in these clonally rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chains, with a preferential use of the VH3 family.24 A recent targeted next-generation sequencing approach showed that MYD88 L265P and CD79b Y196 mutations occur in 44% and 26% of patients with this lymphoma, respectively.25

The predominant lack of germinal center origin of these lymphomas was also confirmed by BCL2 rearrangement, generally absent in IVLBCL; 2 separate cases have reported a t(14; 18) translocation and a tandem triplication of BCL2 at the 18q21 region.25,26 Segmental tandem triplication of the MLL gene, in the q22q25 region of chromosome 11, has been described in a single case, a finding not generally observed.27 Substantial data on the occurrence of “double-hit” cases are not available. Cytogenetic abnormalities have not been well characterized although some studies reported recurrent alterations of chromosome 6.28-30 A single case with t(11; 22)(q23; q11) has been reported, but this aberration was constitutional and not associated with tumor cells.31,32

Pathogenesis

The intrinsic distinctive property of IVLBCL, that is, neoplastic lymphocytes with preferential growth within blood vessel lumina, and its potential mechanisms, has been investigated only in a few studies. IVLBCL cells lack some molecules, such as CD29 (β1 integrin subunit), which are critical for extravasation of lymphocytes.10,33 Based on the limited information mostly obtained in single case reports or very small studies, IVLBCL express Cxc3 and Cxcr4.33,34 These molecules are involved in the regulation of lymphocyte trafficking and integrin activation,34 whereas the tumor-associated endothelial cells do not express their respective ligands (in particular Cxcl12 and, although more controversially, Cxcl9).34,35 A number of homeostatic chemokine receptors such as Cxcr5, Ccr6, and Ccr7, which act on lymphocyte migration across vascular structures,36 were consistently decreased in this lymphoma.37 IVLBCL does not seem to express matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9, 2 molecules important for parenchymal invasion.38 Gene-expression profiles generated by a recently established patient-derived mouse xenograft model of IVLBCL confirmed that inhibition of cell migration could be involved in the pathogenesis of these tumors.39

Overall, these studies confirm that IVLBCL cells express molecules involved in cell migration and molecules that make them capable of adhesion to the endothelium, but lack those involved in extravasation. This latter mechanism seems to be the critical differentiating factor between IVLBCL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The mechanisms that inhibit extravasation most likely rely on multiple defects; therefore, forthcoming studies on this topic are warranted.

The relationship between infectious agents and IVLBCL still remains unclear. Apart from a single case associated with Fasciola and Anisakis,40 human herpes virus-8 has been described occasionally in large B-cell lymphoma with intravascular invasion; these cases are probably unusual presentations of human herpes virus-8–related lymphomas in HIV+ patients rather than IVLBCL.7,8 Epstein-Barr virus41 and human T-lymphotropic virus type I42 have not been reported associated with this kind of tumor.

Clinical features

Classical variant

Upon diagnosis, the median age of patients with IVLBCL is 70 years (range, 34-90 years old), without sex prevalence. The spectrum of its clinical presentation is heterogeneous, due to its near ubiquitous nature (with the exception of lymph nodes) and ranges from monosymptomatic/paucisymptomatic forms, such as fever of unknown origin, pain, or organ-specific local symptoms, to the combination of B symptoms and signs of multiorgan failure.

Rapid deterioration in performance status (PS) is very frequent and elicited by the occurrence of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score ≥1 in the vast majority of patients. Systemic symptoms are present in >50% of patients and occur solely in about a quarter of them. Fever of unknown origin is by far the most common systemic symptom, also in comparison with other aggressive extranodal lymphomas (45% vs 25% of patients, respectively). This symptom represents, per se, an indication for bone marrow biopsy; diagnosis is achieved through this approach. Fever associated with B symptoms occurs in half of cases, whereas weight loss in apyretic patients is present in 10% of patients.

Cutaneous involvement may be present at diagnosis in 40% of patients and displays a wide heterogeneous range of lesions including but not limited to, painful indurate erythematous eruption, poorly circumscribed violaceous plaques, “peau d’orange,” cellulitis, large solitary plaques, painful blue-red palpable nodular discolorations, tumors, ulcerated nodules, small red palpable spots, and erythematous and desquamated plaques.4 These lesions are commonly located in the submammary region and breast, as well as at the extremities and on the lower abdomen. Primary cutaneous lesions are isolated in 30% of patients and are associated with multiple organ involvement in another third of cases.

Highly heterogeneous neurological symptoms, equal or greater in extent to cutaneous ones, are present in 35% of IVLBCL patients. The most frequent manifestations include sensory and motor deficits or neuropathies, meningoradiculitis, paresthesia, hyposthenia, aphasia, dysarthria, hemiparesis, seizures, myoclonus, transient visual loss, vertigo, and altered conscious state.4 Neurolymphomatosis, in particular in relapsing cases, has also been more recently reported.43 IVLBCL presents frequently in the central nervous system (CNS), but rarely is it limited to this system. Neuroimaging is of extreme aid in diagnosis, even when no pathognomonic neuroradiological findings have been described. Ischemic foci are frequent and vasculitis is the most common differential diagnosis. Brain lesions in patients without neurological symptoms are very rare and false-negative results are infrequent. Malignant lymphocytes are rarely detected in cerebrospinal fluid, whereas increased cerebrospinal-fluid protein levels are common.

Two organ-related manifestations deserve consideration: (1) whenever IVLBCL heavily involves endocrine organs (mostly pituitary, thyroid, and adrenal glands) and leads to multiple signs and symptoms of endocrine insufficiency and (2) when lung involvement occurs. Radiology generally presents ground-glass appearance and nodules.44 In this setting, fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scanning is extremely useful in detecting abnormalities, which warrant diagnostic transbronchial lung biopsy.45 Pain, mainly associated with cutaneous lesions or abdominal masses, and fatigue are reported in >30% of patients.4

It should be noted that, in 15% of patients, IVLBCL is associated with different benign nonhematological neoplasms including epithelial,46 soft tissue,47 or vascular tumors.10,48 In all of these, IVLBCL cells are usually, if not exclusively, found within tumor-laden vessels raising the question of potential expression of distinct molecules by these cancer-associated endothelia.

Cutaneous variant

This variant, which exhibits the classical features reported in “Histopathological features,” encompasses 25% of the total IVLBCLs and presents with single or multiple lesions of the skin with negative systemic staging.49 The cutaneous variant is much more frequent in western countries,49 a finding not confirmed by recent Canadian data.5

The clinical characteristics and prognostic profile of this variant differ from classical IVLBCL. Almost all patients are female with normal leukocyte and platelet counts. The monoclonal component, seen in ∼14% of patients with the classical variant, is rarely observed. ECOG-PS is often ≤1. This variant occurs in younger patients with a median age of 59 years (vs 72 years for classical IVLBCL) and the clinical disease progression is less aggressive. Systemic symptoms are present in 30% of cases (vs 65%). These patients survive significantly longer than those with the classical variant (3-year overall survival [OS]: 56% ± 16% vs 22% ± 10%) and the number of cutaneous lesions drives therapeutic choice (refer to “Therapy” later in text).49 The reasons for the better prognosis in the cutaneous variant are not completely understood, but it is likely that an earlier detection and therefore an earlier therapeutic intervention in patients with cutaneous disease may be cardinal.

Hemophagocytic syndrome–associated variant

Patients with this variant display a typical clinical hemophagocytic syndrome, represented by bone marrow involvement, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and thrombocytopenia in 73% to 100% of cases. These findings have not been observed in the classical variant or in the cutaneous form. These distinctive clinical features are very often accompanied by nonneoplastic hemophagocytic histiocytes in peripheral blood or bone marrow smears.3,13 This variant shows a rapid aggressive onset and progression with a median survival time of 2 to 8 months, similar to the known negative prognostic impact of this syndrome in other hematological malignancies. Historically, this variant was referred to as “Asian” because it was almost without exception reported in Asian countries.

In light of these recent findings and advances in knowledge, the recently updated World Health Organization (WHO) classification has suggested, as more appropriate, consideration of IVLBCL variants according to their clinical features (ie, classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic syndrome–associated) rather than by their geographical distribution.2,50

Laboratory findings

Hematological variations include anemia (63% of patients), thrombocytopenia (29%), and leukopenia (24%)4 ; leukopenia or thrombocytopenia usually do not occur without anemia. Among these cytopenias, thrombocytopenia is usually associated with bone marrow infiltration and hepatosplenic involvement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is elevated in 43% of cases, hypoalbuminemia is present in 18% of patients, and a monoclonal serum component is present in 14% of cases. Fifteen percent of cases show altered hepatic, renal, or thyroid functional test results.

Diagnostic considerations

IVLBCL diagnosis is difficult because no pathognomonic signs and symptoms exist. A skilled clinician may suspect the disease based on experience and clinical presentation. Fever of unknown origin concomitant to neurological and cutaneous signs may represent a perfect clinical representation but definitive diagnosis needs to be confirmed by histopathological examination.

Fever of unknown origin may warrant bone marrow biopsy, and skin lesions may warrant a cutaneous biopsy; neurological signs/symptoms, in particular if occurring alone, may represent the rationale for stereotactic biopsy. Abnormal hepatic and renal functional tests also warrant biopsies. Ingravescent dyspnea may justify imaging (including CT scan, PET, or nuclear magnetic resonance imaging), which will show interstitial disease of the lung; this, in turn, will lead to a transbronchial biopsy.

Biopsy following unexplained organ enlargement may reveal IVLBCL as an incidental finding (for instance, in benign prostatic hyperplasia). The presence of fever of unknown origin may justify histopathological examination of macroscopically unaffected organs, such as the skin. In these cases, random skin biopsies, which include the abundant vascular structures of the adipose tissue, could be of aid in diagnosis.51,52 Alternatively, a random transbronchial or gastrointestinal tract biopsy may also be useful.4

Certain peculiar situations, herein briefly described, raise problems in differential diagnosis. Persistent polyclonal B-cell lymphocytosis,53 monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, hairy cell leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, mantle zone lymphoma, splenic marginal zone lymphoma, and hepatosplenic γ-δ lymphoma may display some of their cells within bone marrow vessels. Differential diagnosis from IVLBCL is usually easy due to morphological, immunophenotypical, and clinical features.4 In other cases, such as DLBCLs with primary involvement of the spleen, in particular of the red pulp, associated with splenomegaly, bone marrow may show large B cells within sinusoids.54 In this case, a random tissue biopsy (eg, cutaneous/subcutaneous) may be confirmatory of IVLBCL.

Other B- and T-cell lymphomas can be accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome but only in IVLBCL neoplastic lymphocytes selectively colonize vessel lumina.

Staging of the disease

Current clinical practice indicates that fully reliable staging parameters for IVLBCL are not available. Stage IE disease, according to the Ann Arbor staging system, is present in 40% of patients, most of whom display the cutaneous form or are incidentally diagnosed. These limitations are unfortunately confirmed by cases of death occuring a few weeks after diagnosis in patients clinically interpreted as having stage I lymphoma; at autopsy, though, they exhibit the disseminated disease.

The remaining 60% of IVLBCL patients almost invariably show stage IV disease. The most commonly involved organs are skin, CNS, bone marrow, liver, and spleen. Staging workup of IVLBCL should therefore include routine magnetic resonance imaging of the CNS coupled with bone marrow biopsy, which plays the dual role of both a diagnostic and staging tool. The rare cases with peripheral blood involvement (5%) are invariably associated with bone marrow infiltration.

It is of common knowledge that 15% of diagnosed patients display serological evidence of hepatic, renal, or thyroid impairment; these parameters may be used as surrogates of organ infiltration for staging purposes.

Therapy

The most appropriate therapeutic approach for IVLBCL has been historically difficult to define. The absence of prospective trials is due to the rarity of this disease, and available data often refer to individual case reports or studies that are not numerically powerful.

Perhaps, with the exception of its cutaneous variant, IVLBCL must be considered an aggressive disseminated disease; its treatment relied on the use of combination drugs with well-documented efficacy in patients with DLBCL not otherwise specified. The first choice of treatment of these patients is the use of anthracyclines; the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) regimen is crucial for correct management in most cases. Patients with IVLBCL treated with CHOP achieved an overall response rate of 59%; 33% had a 3-year OS in western countries.55 Poorer results were observed in Japanese patients with hemophagocytic-associated IVLBCL.13

The use of rituximab has significantly changed the evolution of IVLBCL. In patients of the western world, the addition of rituximab to CHOP (R-CHOP) has yielded an 88% complete remission rate, 91% overall response rate, and a 3-year OS in 81% of patients.56,57 In Japan, R-CHOP chemoimmunotherapy has shown 2-year progression-free survival and OS of 56% and 66% of patients, respectively.58 The positive effect of rituximab may be explained by the high drug bioavailability and elevated complement concentrations in the lumina of small vessels. Severe toxic effects of rituximab, such as pulmonary failure, have been reported and require rituximab interruption.58 Severe infusion reactions may be prevented by delaying the administration of rituximab by 3 to 4 days in the first chemoimmunotherapy session. This is particularly true in high-risk patients including those with large tumor burden or severe organ damage and respiratory symptoms even in the absence of radiological signs of disease. Both upfront and salvage treatment of any variant of IVLBCL must include rituximab, yet monotherapy for unfit and frail patients should be considered. The cutaneous variant of IVLBCL, albeit being less aggressive, should be treated in the same way as the other variants. However, single cutaneous lesions of IVLBCL can be managed with radiotherapy in elderly patients with contraindications for chemotherapy; in the remaining cases, radiotherapy should be used only for palliative purposes.

CNS prophylaxis and treatment is another important therapeutic component in IVLBCL patients.3 Extravascular CNS dissemination accounts for the main site of disease in western patients with relapsing IVLBCL treated upfront with R-CHOP.57 Because current neuroimaging may not recognize the dissemination,59 the addition of drugs with a better CNS bioavailability, such as high-dose methotrexate, represents a possible strategy.3 The widespread increase in use of rituximab has led to a remarkably improved outcome and survival figures that overlap those reported for patients with DLBCL not otherwise specified. In fact, a recent population-based study reported a 5-year OS of 46.4% and 46.5%, respectively.60

The use of high-dose chemotherapy supported by autologous stem cell transplantation remains a matter of debate. In a retrospective study, autologous stem cell transplantation showed a clinical improvement in comparison with R-CHOP treatment. However, it appears feasible only in a small proportion of patients with IVLBCL considering a median age of 70 years and generally poor PS61 in which this option cannot be applied. Experience with new drugs is limited and cases with poor success have been reported. Interestingly, an autoptic case of disseminated IVLBCL showed strong programmed death ligand 1 expression on neoplastic lymphocytes; this finding may display important therapeutic implications.62 International cooperative efforts are needed in order to pursue new drug development.

Perspectives

Despite these unexpected and recent achievements, many questions still remain open. The biological properties of neoplastic cells still remain unclear. Immunophenotype, the differences between classical and hemophagocytic variants, the relationship of the disease associated with solid tumors or other lymphomas, and a more detailed characterization of cytogenetic and cytokine/adhesion molecules are aspects that still need to be investigated. Adequate clinical recognition and standard staging should be put in place. Furthermore, an appropriate therapeutic approach needs to be found in order to further ameliorate the management of this fascinating disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Andrés J. M. Ferreri for useful insights on clinical and therapeutic aspects of IVLBCL, and Lucia Bongiovanni for photographic assistance.

This work was supported by Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad grant no. SAF2015-64885-R (E.C.).

E.C. is an Academia Researcher of the Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA) of the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Authorship

Contribution: M.P. assembled and wrote the manuscript; and E.C. and S.N. structured and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Maurilio Ponzoni, Pathology Unit, Unit of Lymphoid Malignancies, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Ateneo Vita-Salute, Via Olgettina 60, 20132 Milan, Italy; e-mail: ponzoni.maurilio@hsr.it.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal