In this issue of Blood, Huls et al present positive results from a randomized study (HOVON97) showing that disease-free survival (DFS) in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was improved by azacitidine compared with postremission observation.1

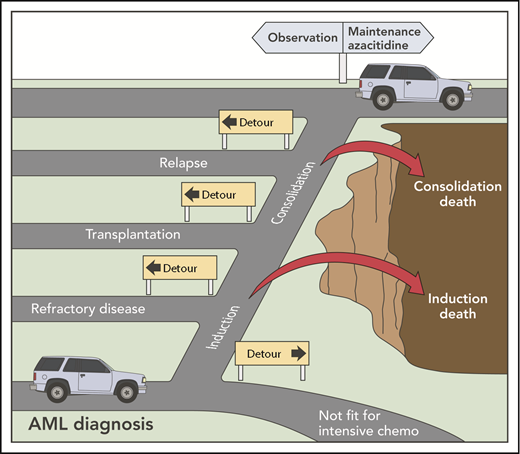

The hazardous and detour-laden road to maintenance therapy in AML. chemo, chemotherapy. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

The hazardous and detour-laden road to maintenance therapy in AML. chemo, chemotherapy. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Relapse after intensive induction and consolidation therapy remains the most important cause of treatment failure in AML. For older patients, the risk of relapse after intensive chemotherapy is 50% to 80%.2 Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is an accepted option for select older patients with adverse cytogenetic and molecular risk factors. The role of maintenance therapy in reducing relapse risk in patients who do not receive transplants remains controversial.

Prior randomized studies have suggested clinical benefit for several maintenance strategies, including low-dose cytarabine, recombinant interleukin 2/histamine dihydrochloride, or attenuated chemotherapy (reviewed in Rashidi et al3 ). Many of these studies suffered from small sample size and concerns that the first-line chemotherapy was suboptimal by today’s standards. A French study conducted in older patients demonstrated a delayed survival benefit for patients receiving 2 years of maintenance therapy with norethandrolone, an androgen analog.4 The uncertain mechanism of action and limited norethandrolone availability worldwide have limited broad adoption and further exploration of this strategy. FLT3 inhibitors have also been actively explored in maintenance for patients with FLT3-mutant AML, with evidence strongest for their use in the postallograft setting.3,5

Recruitment of patients to maintenance studies may be challenging. A UK National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) study found that only 28% of older patients initially registered to receive intensive chemotherapy (in first remission to maintenance azacitidine or not) underwent randomization.6 This is typical of most maintenance studies, where enrolled patients represent a small fraction of the starting population. Patients need to survive intensive chemotherapy, achieve and remain in remission, and not be candidates for allo-HCT (see figure). Parenteral drug administration and concerns regarding potential drug toxicity may represent further deterrents to maintenance trial participation.

Against this backdrop, the results from the HOVON97 trial are intriguing. The study randomized 116 eligible patients 60 years of age or older in complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) after 2 cycles of intensive chemotherapy. Recruitment took 6.5 years, more than double the planned accrual time of 3 years, resulting in termination of the study prior to the planned recruitment target. Despite this, the primary end point was met, with DFS significantly improved from 10.3 to 15.9 months in the azacitidine arm. Treatment appeared tolerable, with almost two-thirds completing the 12 cycles of protocol treatment. Post hoc analyses suggested that azacitidine increased DFS for patients in CR or with a baseline platelet count of ≥100 × 109/L. In contrast, a benefit for azacitidine was not apparent for patients in CRi or with a platelet count of <100 × 109/L. These results suggest the possibility that maintenance azacitidine may have the optimal effect in patients with higher-quality potentially measurable residual disease–negative (MRD−) disease (see below).

In support of this hypothesis, the UK NCRI has presented preliminary data on the role of azacitidine maintenance in patients older than 60 years of age with AML in CR after 2 courses of intensive chemotherapy.6 They found a significant survival benefit for azacitidine maintenance among patients without detectable measurable residual disease by flow cytometry (MRD−), whereas a benefit for azacitidine was not observed in MRD+ patients, suggesting that maintenance therapy had the highest utility in patients with chemosensitive disease. This raises the question of whether MRD+ patients should instead be considered for alternative salvage approaches.

Will the HOVON97 study establish azacitidine maintenance as the standard of care for AML? The study certainly indicates the likelihood of a clinical effect from azacitidine in the postremission phase of therapy. Although maintenance was administered for a maximum of 12 cycles, it is unknown whether a longer period of maintenance treatment could have further improved DFS. In addition, overall survival (OS) was not significantly improved, although the study was not powered to show superiority for this end point. It is likely, however, that another confirmatory study using a more convenient azacitidine-dosing formulation on the back of this study could provide strong support for maintenance therapy as a standard approach for this group of elderly AML patients.

Indeed, a phase 3 randomized maintenance study (QUAZAR) has completed accrual, randomizing over 460 patients to 24 months of CC-486 (Celgene Corporation), an oral azacitidine analog vs placebo, in patients 55 years of age or older with AML in first CR or CRi after intensive chemotherapy.7 The primary end point was OS. If this study is positive, it is likely that maintenance therapy will be accepted as a new standard of care for patients with AML. The HOVON97 study represents an important contribution to the positive potential of postremission maintenance therapy in AML. Remission induction and consolidation should now be considered the first step of a patient’s AML journey. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels demonstrate persistence of recognized AML mutations in ∼30% of patients in CR after intensive induction chemotherapy.8 This excludes age-related DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1 mutations, whose long-term relevance as markers of leukemic relapse remains uncertain. When NGS was combined with flow cytometry, MRD detected by either or both techniques was present in ∼40% of patients and associated with relapse in 50% to 73% of cases, compared with 27% among patients without MRD. With standardized guidelines now available for the measurement and definition of MRD, the future incorporation of MRD monitoring and guided intervention during the postremission phase of AML is now a real possibility.9 It is likely that postremission therapies could be further risk-adapted to incorporate or combine more target-directed options in the future, with FLT3 and isocitrate dehydrogenase inhibitors obvious candidates. With promising results from multicycle low-intensity treatment options in combination with the targeted B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor venetoclax reported, the distinction between induction, consolidation, and maintenance phases of treatment are already starting to blur.10 The concept of maintenance therapy is moving from one of clinical uncertainty to one of clinical necessity. Therefore, for maintenance therapy in AML, although we are not quite “there yet,” we are certainly getting very close.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author is a medical advisor and receives honoraria and research funding from Celgene.