Abstract

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory drug approved in the United States for use with rituximab in patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. We reviewed data from trials addressing the safety and efficacy of lenalidomide alone and in combination with rituximab as a first-line therapy and as a treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. Lenalidomide-rituximab has been demonstrated to be an effective chemotherapy-free therapy that improves upon single-agent rituximab and may become an alternative to chemoimmunotherapy.

Introduction

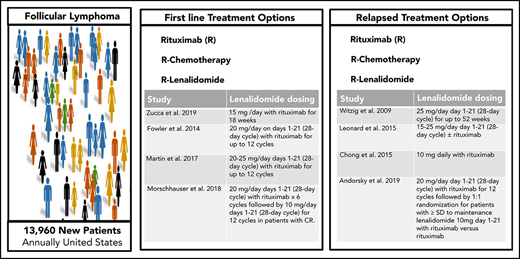

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common form of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma with approximately 13 960 new individuals diagnosed annually in the United States.1 With improvements in outcomes over time, most patients can anticipate a normal life expectancy despite a diagnosis of FL, although a fraction die of the disease, indicating the need for better therapies.2 Although numerous options exist for first-line therapy, FL commonly presents as a slow-growing cancer with indolent behavior that permits an initial period of observation, and immediate treatment is not required or recommended for many patients with FL who are asymptomatic after diagnosis. However, FL is characterized by heterogeneous clinical presentations and outcomes. FL continues to be considered incurable despite the improvements in overall survival (OS) observed over the past few decades.3-6 Although a number of highly effective treatment options exist, there is no universally agreed upon standard treatment approach in the first-line or the relapsed/refractory setting (Table 1).

Clinical trials involving follicular lymphoma patients treated in the first-line and relapsed settings

| Reference . | Dose regimen . | Response rate . | PFS . |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line follicular lymphoma | |||

| Zucca et al9 | 15 mg /d with rituximab for 18 wk | OR, 82%; CR, 36% | Median, 5 y |

| Fowler et al10 | 20 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab for up to 12 cycles. | OR, 98%; CR, 87% | Median not reached* |

| 3 y, 79% | |||

| Martin et al11 | 20-25 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab for up to 12 cycles | OR, 95%; CR, 72% | 5.y, 72% |

| Morschhauser et al13 | 20 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab ×6 cycles followed by 10 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) for 12 cycles in patients with confirmed or unconfirmed CR. | OR, 61%; CR, 48% | 3 y. 77% |

| Relapsed follicular lymphoma | |||

| Witzig et al15 | 25 mg/d day 1-21 (28-d cycle) for up to 52 wk | OR, 27%; CR, 9% | Median, 4.4 mo |

| Leonard et al17 | 15-25 mg/d day 1-21 (28-d cycle), with or without rituximab | Lenalidomide | Lenalidomide: |

| OR, 53%; CR, 20% | Median time to progression, 1.1 y | ||

| Lenalidomide+rituximab: | Lenalidomide+rituximab: | ||

| OR, 76%; CR, 39% | Median time to progression, 2 y | ||

| Chong et al16 | 10 mg daily with rituximab | OR, 65%; CR, 35% | Median, 16.5 mo |

| Andorsky et al19 | 20 mg/d, day 1-21 (28-d cycle), with rituximab for 12 cycles, followed by 1:1 randomization of patients with ≥ stable disease to maintenance lenalidomide 10 mg, d 1‐21, with rituximab vs rituximab alone | OR, 74%; CR, 46% (for induction phase) | Median, 0.2 mo |

| Leonard et al18 | 20 mg/d day 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab for 12 cycles | OR, 78%; CR, 34% | Median, 39.4 mo |

| Reference . | Dose regimen . | Response rate . | PFS . |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line follicular lymphoma | |||

| Zucca et al9 | 15 mg /d with rituximab for 18 wk | OR, 82%; CR, 36% | Median, 5 y |

| Fowler et al10 | 20 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab for up to 12 cycles. | OR, 98%; CR, 87% | Median not reached* |

| 3 y, 79% | |||

| Martin et al11 | 20-25 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab for up to 12 cycles | OR, 95%; CR, 72% | 5.y, 72% |

| Morschhauser et al13 | 20 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab ×6 cycles followed by 10 mg/d days 1-21 (28-d cycle) for 12 cycles in patients with confirmed or unconfirmed CR. | OR, 61%; CR, 48% | 3 y. 77% |

| Relapsed follicular lymphoma | |||

| Witzig et al15 | 25 mg/d day 1-21 (28-d cycle) for up to 52 wk | OR, 27%; CR, 9% | Median, 4.4 mo |

| Leonard et al17 | 15-25 mg/d day 1-21 (28-d cycle), with or without rituximab | Lenalidomide | Lenalidomide: |

| OR, 53%; CR, 20% | Median time to progression, 1.1 y | ||

| Lenalidomide+rituximab: | Lenalidomide+rituximab: | ||

| OR, 76%; CR, 39% | Median time to progression, 2 y | ||

| Chong et al16 | 10 mg daily with rituximab | OR, 65%; CR, 35% | Median, 16.5 mo |

| Andorsky et al19 | 20 mg/d, day 1-21 (28-d cycle), with rituximab for 12 cycles, followed by 1:1 randomization of patients with ≥ stable disease to maintenance lenalidomide 10 mg, d 1‐21, with rituximab vs rituximab alone | OR, 74%; CR, 46% (for induction phase) | Median, 0.2 mo |

| Leonard et al18 | 20 mg/d day 1-21 (28-d cycle) with rituximab for 12 cycles | OR, 78%; CR, 34% | Median, 39.4 mo |

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory drug initially approved for use in multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma and recently approved for use with rituximab in the relapse setting for FL. Lenalidomide produces antitumor activity by multiple mechanisms that may vary across lymphoid malignancies. Studies of lenalidomide in FL have demonstrated that this agent activates CD8 T cells, reduces the numbers of regulatory T cells, enhances T-cell immune synapses, and increases the ratio of T-helper 1 subsets over T-helper 2 subsets.7,8 However, this understanding of the effect of lenalidomide on lymphoma tumor and host immune system biology has yet to lead to the development of biomarkers to aid in the selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment. Such biomarkers would be helpful in selecting FL patients most likely to benefit from lenalidomide and rituximab in the first line and relapse settings and to determine the ideal dosage and schedule for administration in the future.

Lenalidomide and rituximab as a first-line therapy for FL

The Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Nordic Lymphoma Group performed a phase 2 trial that compared the activity of rituximab 375 mg/m2 given weekly for 4 weeks and repeated on weeks 12 to 15 in responding patients (n = 77) to that of rituximab given on the same schedule with lenalidomide 15 mg daily for 18 weeks (n = 77), in previously untreated FL patients in need of therapy.9 This trial demonstrated that the group receiving combination therapy had a significantly higher complete response (CR) rate at 6 months by independent response review of computed tomographic scans (61% vs 36%), longer progression-free survival (PFS, 5 vs 2.3 years), and more adverse events of grade 3 or higher (56% vs 22%), although this increase in toxicity was manageable in the view of the investigators. As discussed below in the section on the AUGMENT trial, a trial involving a similar comparison supported approval of lenalidomide-rituximab in the relapse setting. Bolstered by the favorable outcomes and excellent OS observed for both arms of this phase 2 study, including some FL patients in need of treatment with considerable disease burden (47% with high-risk FL International Prognostic Index [FLIPI]; 41% with tumor bulk >6 cm; and 21% with high lactate dehydrogenase), the researchers advocated that chemotherapy-free first-line regimens be further explored.

Other investigators have pursued lenalidomide and rituximab as a possible chemotherapy-free approach to first-line therapy for FL. In a single-arm trial, Fowler and colleagues10 at MD Anderson administered lenalidomide 20 mg/d on days 1 to 21 of a 28-day cycle, with rituximab administered on day 1. Patients who responded at 6 cycles continued treatment of up to 12 cycles. Forty-five of 46 evaluable patients with FL responded (CR, 87%). Across all patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma the most common adverse events of grade 3 or higher were neutropenia (38 of 110 patients; 35%), myalgia (9%), rash (7%), fatigue (5%), thrombosis (5%), and pulmonary symptoms (5%). In a multicenter phase 2 trial led by the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, lenalidomide 20 to 25 mg was administered on days 1 to 21 of a 28-day cycle, with rituximab administered on day 1 of cycles 1, 4, 6, 8, and 10, for up to 12 cycles to patients with previously untreated FL (n = 66).11 Overall response (OR, 95%) and CR (72%) rates were similarly high, and toxicities were comparable. The most common reasons for early discontinuation of treatment were study withdrawal (n = 6), adverse events (n = 6), and progression (n = 2).

These provocative data prompted evaluation as to whether lenalidomide and rituximab could be superior to chemoimmunotherapy. In the phase 3 RELEVANCE study (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01476787 and NCT01650701), 1030 subjects with previously untreated high-tumor-burden FL were randomized to receive rituximab with chemotherapy followed by maintenance rituximab as the standard of care (defined by the PRIMA trial)12 or lenalidomide-rituximab with maintenance rituximab.13 Lenalidomide was administered at 20 mg/d for 21 days of a 28 day cycle for the first 6 cycles followed by 10 mg/d for 12 cycles in patients with confirmed or unconfirmed CR. The primary objective was to establish the superiority of lenalidomide-rituximab, when measured by CR at 30 months14 or by PFS. Although median PFS has yet to be reached, the published analysis demonstrated that CR at 30 months was not superior in either arm. The efficacy of lenalidomide-rituximab was similar to rituximab and chemotherapy based on response rates and 3-year PFS, regardless of risk profile. Rituximab-chemotherapy more commonly produced grades 3 and 4 cytopenia and febrile neutropenia, whereas lenalidomide-rituximab more commonly resulted in rash. The differences in toxicity profile offer distinct options for patients with comparable efficacy, albeit with relatively limited follow-up. Other challenges to using rituximab in first line remain, including questions about reimbursement, late effects, optimal dosage and schedule, and responses to subsequent chemoimmunotherapy regimens in the second, third, and later lines. Moreover, the relative value of earlier vs later treatment with lenalidomide remains uncertain, given that there is also evidence of benefit from its use in later lines of therapy after rituximab or chemoimmunotherapy, as discussed in the following section. The development of tools profiling the immune system of the patient and/or the tumor microenvironment may be useful predictive biomarkers to guide treatment selection, dosing, and duration for lenalidomide-based regimens in the future.

Lenalidomide alone and with rituximab in relapsed FL

The single-agent activity of lenalidomide was evaluated in 43 patients with relapsed/refractory indolent lymphoma in a study by Witzig and colleagues.15 Patients received a median of 3 prior systemic therapies (range, 1-17), and half were refractory to their most recent therapy. Lenalidomide alone was administered at a dose of 25 mg daily on days 1 to 21 of a 28-day cycle for up to 52 weeks. The OR rate was 23% for the entire population and 26% in patients with FL; the median PFS for the population was 4.4 months). Although the single-agent dose of 25 mg of lenalidomide was viewed as tolerable by the researchers, lower doses of lenalidomide have been selected for use in combination in indolent lymphomas, particularly when used as a part of maintenance therapy.

In a phase 2 study, 26 patients with rituximab-refractory FL received lenalidomide 10 mg daily for 8 weeks followed by weekly rituximab 375 mg/m2 for 4 weeks, with lenalidomide continued during and after rituximab. Five of 26 patients (19%) responded after lenalidomide and 17 of 26 (65%) responded after lenalidomide and rituximab, including 9 CRs with a median PFS of 16.5 months.16 However, assessment of efficacy in this trial was confounded by the administration of dexamethasone to approximately one-half of the patients. A randomized trial led by the Alliance evaluated lenalidomide alone (n = 45) and lenalidomide plus rituximab (n = 46) in patients with relapsed FL. In this study, lenalidomide started at a dose of 15 mg per day on days 1 to 21 followed by 7 days of rest, with escalation in cycle 2 to 20 mg/d in patients who did not require a delay; in cycle 3 and beyond, the dose was escalated to 25 mg/d. The response rate was 53% in patients receiving lenalidomide (20% CR) and 76% in patients receiving lenalidomide and rituximab (39% CR).17 Adverse events of grade 3 or higher occurred in 58% and 52% of patients receiving lenalidomide and lenalidomide-rituximab, respectively, without significant differences in common adverse events, including neutropenia, fatigue, rash, and thrombosis. These studies demonstrate improved efficacy with the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab over lenalidomide alone, with reasonable toxicity in this context.

The multicenter, phase 3 randomized trial (AUGMENT; clinicaltrials.gov NCT01938001) of lenalidomide plus rituximab (n = 178) vs placebo plus rituximab (n = 180) enrolled patients with relapsed and/or refractory FL or marginal zone lymphoma.18 Patients received lenalidomide 20 mg/d on days 1 to 21 or placebo for 12 cycles plus rituximab weekly for 4 weeks in cycle 1 and on day 1 of cycles 2 through 5. Although infections (63% vs 49%), neutropenia (58% vs. 23%), and rash (32% vs 12%) were more common with lenalidomide-rituximab, the median PFS was longer for lenalidomide-rituximab (39 months vs 14.1 months). The secondary end points of time to next chemotherapy treatment, time to next antilymphoma treatment, and PFS on next antilymphoma treatment were also significantly better for lenalidomide-rituximab. A second multicenter, nonregistrational phase 3b trial (MAGNIFY; clinicaltrials.gov NCT01996865) also enrolled patients with relapsed and/or refractory FL or marginal zone lymphoma and administered lenalidomide 20 mg/day on days 1 to 21 of a 28-day cycle with rituximab for 12 cycles followed by 1:1 randomization of patients with stable disease or better to continued lenalidomide-rituximab or rituximab maintenance.19 During the maintenance phase, lenalidomide was administered at 10 mg on days 1 to 21 of a 28-day cycle, with rituximab. So far, the data reported for MAGNIFY involve only the induction phase; data on the randomized component have not yet been reported. With a median follow-up (16.7 months), the toxicity profile, the response rate (74%, 46% CR), and the median PFS (30.2 months) of patients with FL observed in this study confirm findings from other trials. Based on data from these studies, lenalidomide-rituximab provides a useful alternative to chemoimmunotherapy for some patients with relapsed FL and significantly improves outcomes with modestly increased toxicity in situations where single-agent rituximab would otherwise have been used.

Determining optimal use and dosage of lenalidomide with rituximab

The recent approval of lenalidomide-rituximab adds to the broad array of tools at our disposal for continuing to improve outcomes for patients with FL. These include a host of approved agents and combinations such as: rituximab, obinutuzumab, radioimmunotherapy, chemotherapy alone or in combination with anti-CD20 antibodies, and the PI3-kinase inhibitors, idelalisib, duvelisib, and copanlisib. Whereas some of these agents and regimens are commonplace and have gained widespread use, others have been abandoned, and still others are attempting to find niches. The variability in presentation at diagnosis and relapse results in profound variation in initial and subsequent management strategies used for the care of patients with FL, ranging from observation to intensive chemoimmunotherapy, making the care of individuals with FL complex and challenging for patients and physicians.

Given the concerns for toxicity associated with currently approved PI3-kinase inhibitors and chemotherapy-based regimens in relapsed FL, the use of lenalidomide-rituximab is likely to become more commonplace for relapsed FL. PI3k inhibitors are approved and still may be useful in patients with refractory FL. Although bendamustine and obinutuzumab is approved in the relapse setting, bendamustine with an anti-CD20 antibody is commonly used as a first-line regimen, which reduces the likelihood of the use of this regimen at relapse. The combination of lenalidomide and rituximab should be used over Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors in relapsed FL. BTK inhibitors are not approved for FL but have been administered by some practitioners in this setting. Moreover, although these agents all have activity in B-cell lymphomas, lenalidomide and rituximab should not be combined with BTK inhibitors or PI3-kinase inhibitors. A trial combining lenalidomide, rituximab, and ibrutinib produced rash in 82% of patients without improvement in efficacy20 and trials of lenalidomide, rituximab, and idelalisib were closed early because of unexpected dose-limiting toxicities.21 One promising future application of lenalidomide combination therapy is being explored in the US intergroup trial S1608 (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03269669), a randomized phase 2 study comparing obinutuzumab and lenalidomide vs obinutuzumab with chemotherapy vs obinutuzumab and umbralisib in patients with FL who experienced early treatment failure after frontline chemoimmunotherapy.

The most widely used FL risk stratification model has been the FLIPI, which includes age, stage, hemoglobin level, number of nodal areas, and serum LDH levels.22 FLIPI can be useful for comparing clinical trial populations or cohorts in observational studies. However, neither FLIPI nor any other risk stratification tool has gained traction for individual patient decision making. With the broad armamentarium of agents now available for patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed FL predictive algorithms and biomarkers are needed to aid in therapy selection. In addition, consensus from experts and practice groups on optimal treatment strategies should be based on evidence from trials like those discussed herein, and those strategies should drive the use of approaches and treatment sequences with the greatest likelihood of benefitting patients through reduced toxicity and increased efficacy. As clinicians gain experience with lenalidomide-rituximab dosage and administration in FL, assessment of key features measured in clinical practice and emerging data from new and maturing trials should be used to guide the use of this new combination treatment of FL in the future.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant CA208132.

Authorship

Contribution: C.R.F. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and J.P.L. and N.H.F. performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.R.F. has served as a consultant for Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Celgene/Bristol Meyers Squibb (unpaid), Denovo Biopharma, Genentech/Roche (unpaid), Gilead, OptumRx, Karyopharm, Pharmacyclics/Janssen, Spectrum and has received research funding from Abbvie, Acerta, BeiGene, Celgene/Bristol Meyers Squibb, Gilead, Genentech/Roche, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Millennium/Takeda, Pharmacyclics, TG Therapeutics, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, National Cancer Institute, and the V Foundation. J.P.L. has served as a consultant for Sutro, Bayer, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Celgene/Bristol Meyers Squibb, Merck, Morphosys, BeiGene, Nordic Nanovector, Roche/Genentech, ADC Therapeutics, Sandoz, Karyopharm, Miltenyi, Akcea Therapeutics, and Epizyme. N.H.F. has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Janssen, Celgene, and TG Therapeutics; has received research funding from AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen, and Roche, and TG Therapeutics; and has received paid travel, accommodations, and expenses from Celgene and Janssen.

Correspondence: Christopher R. Flowers, Department of Lymphoma/Myeloma, MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 429, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: crflowers@mdanderson.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal