In this issue of Blood, Grebe et al1 report that changing the US blood donation policy for men who have sex with men (MSM) from an indefinite deferral to a deferral of 12 months from last sex did not significantly increase the risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV. In an accompanying article, Custer et al2 demonstrate that HIV-positive individuals on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and individuals taking HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are donating blood, potentially increasing the risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV.

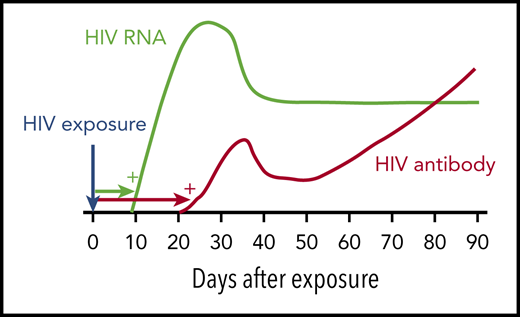

HIV window period. Following HIV infection, HIV RNA becomes detectable by standard NAT after ∼9 to 10 days (green). HIV antibody is detectable by immunoassay after ∼21 days (red). Blood donations made in the HIV NAT window period are responsible for most of the residual risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV. Adapted from Busch10 with permission from the author and publisher.

HIV window period. Following HIV infection, HIV RNA becomes detectable by standard NAT after ∼9 to 10 days (green). HIV antibody is detectable by immunoassay after ∼21 days (red). Blood donations made in the HIV NAT window period are responsible for most of the residual risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV. Adapted from Busch10 with permission from the author and publisher.

In developed countries, blood centers protect the safety of the blood supply by deferring high-risk donors and screening all donations for HIV and other pathogens using exquisitely sensitive and specific assays. This multilayered approach has been highly successful. In the United States and many other countries, the per-unit risk of HIV transfusion-transmission is <1 per million.3 However, medical policies and practices continue to evolve, and so do the risks of transfusion-transmitted infection. In this issue of Blood, Custer and colleagues report 2 important studies about current risks of transfusion-transmitted HIV. One of these studies is reassuring1 ; the other is not.2

HIV antibodies become detectable in blood ∼21 days after infection. HIV nucleic acid testing (NAT) turns positive earlier, ∼9 to 10 days after infection. Thus, HIV NAT is considered to have a window period of ∼9 days (see figure). For donor screening, HIV NAT is typically performed on mini-pools (samples from, eg, 16 donors). If a pool tests positive, the individual samples are tested to identify the HIV-positive donation. Window period donations represent almost all of the residual risk of HIV transfusion-transmission. In these rare cases, an individual donates soon after getting infected with HIV, when the viral RNA load is still very low and before specific antibody is detectable. The screening tests result as negative, and the donated unit may infect a transfusion recipient.

Policies on donor eligibility, reflected in the predonation Donor History Questionnaire, are intended to prevent individuals with high-risk behaviors from donating in the window period. These policies are often viewed as discriminatory by gay communities; regulators such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) try to balance protecting the blood supply with making donation as widely available as possible. In 2000, Australia became the first nation to make MSM a 12-month donor deferral instead of an indefinite deferral. Other countries followed suit, including the United States in 2015.4 In April 2020, the FDA reduced the deferral period for MSM to 3 months from last sex,5 consistent with policies elsewhere. Intuitively, adopting a 12- or 3-month MSM deferral period should not increase the risk of HIV-contaminated units entering the blood supply given a window period of only 9 days.

However, policy changes can have unintended consequences. Grebe et al decided to examine whether the switch in the United States from an indefinite deferral to a 12-month deferral led to an increase in higher-risk individuals donating blood and a corresponding increase in the risk of transfusion-transmitted HIV. Using data from several US blood centers, the investigators measured the HIV incidence in first-time blood donors before and after the switch to a 12-month MSM deferral. The incidence of HIV in first-time donors was 2.62/105 person-years at baseline and 2.85/105 person-years after the 12-month deferral was implemented (not significantly different). Using a mathematical model,6 Grebe et al estimated that the per-unit risk of HIV transfusion-transmission changed from 0.32 per million at baseline to 0.35 per million, again not significantly different.

The FDA mandated an indefinite deferral for MSM in 1985, a time when HIV was invariably fatal. In the decades that followed, ART and PrEP completely changed the landscape. The current Undetectable Equals Untransmittable (U = U) campaign stresses that HIV-infected individuals on ART who have undetectable viral loads cannot sexually transmit HIV. However, complying with a daily ART regimen is challenging, and stopping ART leads to HIV rebound.7 Although the U = U paradigm has been proven for sexual transmission of HIV, U = U may not apply for transfusion-transmission.8 Besides suppressing HIV RNA, ART can cause HIV antibody levels to drop, potentially creating a scenario where an HIV-infected donor with a low viral load could be missed by the screening tests. Custer et al looked for biochemical evidence that US blood donors were taking ART. What they found was sobering. The investigators obtained blood samples from 299 HIV-positive donors and 300 control donors with nonreactive screening tests. The samples were assayed for ART compounds in blinded fashion using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Evidence for ART was found in 46 samples from the HIV-positive donors (15.4%), but in zero control samples. It would appear that a number of blood donors knew that they had HIV but donated anyway.

Custer et al conducted 2 related studies aimed at determining if blood donors were taking PrEP. The investigators obtained samples from first-time male donors from 6 US cities. Of 1494 samples tested, 9 (0.6%) were positive by LC-MS for both tenofovir and emtricitabine. The investigators also analyzed data from MSM who participated in the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance survey. Among 565 HIV-negative respondents, 27 (4.8%) reported donating blood after recently taking PrEP.

The observation that a nontrivial number of blood donors are taking ART or PrEP represents a safety gap in the blood collection system. As the authors note, we need to further evaluate the risk of HIV transmission from donors on ART or PrEP, and we will need to conduct new studies of donor comprehension and motivation. AABB (formerly, the American Association of Blood Banks) has already added ART and PrEP agents to the list of drugs requiring donor deferral. HIV testing could be made more sensitive by switching from mini-pools to individual donation NAT. However, human behavior will remain unpredictable, and tests will always have limits. Pathogen reduction may eventually provide a fail-safe solution to transfusion-transmitted HIV, but a method to sterilize a whole blood donation has not been FDA approved yet. In any case, Custer et al are to be commended for their rigorous and imaginative studies demonstrating that changing HIV policies and practices may have surprising implications for blood safety.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal