Key Points

Increased platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation associate with poor outcome in severe COVID-19 patients.

Platelets from severe COVID-19 patients induce monocyte TF expression through P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3 signaling.

Abstract

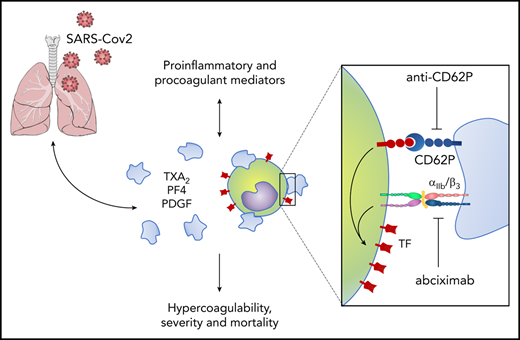

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is an emergent pathogen responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Since its emergence, the novel coronavirus has rapidly achieved pandemic proportions causing remarkably increased morbidity and mortality around the world. A hypercoagulability state has been reported as a major pathologic event in COVID-19, and thromboembolic complications listed among life-threatening complications of the disease. Platelets are chief effector cells of hemostasis and pathological thrombosis. However, the participation of platelets in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 remains elusive. This report demonstrates that increased platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation are observed in severe COVID-19 patients, but not in patients presenting mild COVID-19 syndrome. In addition, exposure to plasma from severe COVID-19 patients increased the activation of control platelets ex vivo. In our cohort of COVID-19 patients admitted to the intensive care unit, platelet-monocyte interaction was strongly associated with tissue factor (TF) expression by the monocytes. Platelet activation and monocyte TF expression were associated with markers of coagulation exacerbation as fibrinogen and D-dimers, and were increased in patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation or patients who evolved with in-hospital mortality. Finally, platelets from severe COVID-19 patients were able to induce TF expression ex vivo in monocytes from healthy volunteers, a phenomenon that was inhibited by platelet P-selectin neutralization or integrin αIIb/β3 blocking with the aggregation inhibitor abciximab. Altogether, these data shed light on new pathological mechanisms involving platelet activation and platelet-dependent monocyte TF expression, which were associated with COVID-19 severity and mortality.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the new human coronavirus SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),1 is responsible for the current pandemic with >4.8 million cases and 323 000 deaths reported globally.2 Despite its tropism to the lungs, a hypercoagulability state is frequently present in COVID-19 patients.3-5 Thrombotic complications, including venous or arterial thromboembolism, have been related to increased mortality in COVID-19.3,5 Thrombocytopenia and increased levels of D-dimers have proved as early predictors of outcome in critically ill COVID-19 patients.3,6-11 However, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying COVID-19–associated hypercoagulability are still to be defined.

Platelets are anucleate blood cells classically known by their roles in hemostasis and pathological thrombosis.12 Beyond hemostatic activities involving platelet aggregation and thrombus formation, platelets also coordinate vascular function and integrity by complex interactions with endothelial cells and leukocytes.12-14 Activated platelets reprogram cellular functions of adjacent cells by heterotypic cellular interactions and juxtracrine signals from P-selectin and integrins.15-17 Platelets modulate critical leukocyte responses such as migration,14,18 secretion,19,20 extrusion of neutrophil extracellular traps,21 recruitment to growing thrombi,17,22 and monocyte expression of tissue factor (TF),23-25 an essential trigger of coagulation and thrombosis.26 Therefore, platelet-leukocyte interactions are indispensable events in physiological and pathological hemostasis and inflammation.14,22,27,28 Our group and others have previously shown that platelet activation and platelet-leukocyte interactions participate in the pathophysiology of viral infections, including dengue, HIV, and influenza.20,29-35 Our central hypothesis is that platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation participate in thromboinflammatory responses during COVID-19.

Here, we investigate platelet activation and its involvement in the hypercoagulability state in patients with COVID-19. We provide novel evidence that critically ill COVID-19 patients exhibit increased platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregates. We show that platelet-monocyte interaction is determinant to TF expression in the monocytes through mechanisms involving P-selectin– and integrin αIIb/β3-dependent signaling. Our data shed new light on pathological mechanisms involving platelet activation and platelet-dependent monocyte TF expression, which are associated with severity and mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

Material and methods

Human subjects

We prospectively enrolled severe or mild/asymptomatic COVID-19 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-confirmed cases and SARS-CoV-2-negative (SARS-CoV-2−) controls. Blood and respiratory samples were obtained from the 35 patients with severe COVID-19 within 72 hours from intensive care unit (ICU) admission in 2 reference centers (Instituto Estadual do Cérebro Paulo Niemeyer and Hospital Copa Star, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Severe COVID-19 was defined as those critically ill patients presenting viral pneumonia on computed tomography scan and requiring oxygen supplementation through either a nonrebreather mask or mechanical ventilation. Four outpatients presenting mild self-limiting COVID-19 syndrome and 2 SARS-CoV-2-positive (SARS-CoV-2+) asymptomatic subjects were also included. All patients had SARS-CoV-2 confirmed diagnostic through RT-PCR of nasal swab or tracheal aspirates. Peripheral vein blood was also collected from 11 SARS-CoV-2− control participants as tested by RT-PCR on the day of blood sampling. The characteristics of severe (n = 35), mild/asymptomatic (n = 6), and control (n = 11) participants are presented in Table 1. Mild and severe COVID-19 patients presented differences regarding age and the presence of comorbidities such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes (Table 1), which is consistent with previous reports.36-38 The SARS-CoV-2− control group, however, included subjects of older age and chronic noncommunicable diseases, matching mild and critical COVID-19 patients, except for hypertension (Table 1).

Characteristics of COVID-19 patients and control subjects

| Characteristics . | Control, n = 11 . | Mild/ asymptomatic, n = 6 . | Severe, n = 35 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53 (32-60) | 32 (30-34) | 57 (47-64) |

| Sex, male | 4 (28.6) | 2 (33.3) | 17 (48.6) |

| Respiratory support | |||

| Oxygen supplementation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (22.8) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (77.1) |

| SAPS 3 | 60 (47-68) | ||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | — | — | 150 (101-258) |

| Vasopressor | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (45.7) |

| Time from symptom onset to blood sample, d | — | 6 (1-12)† | 12 (8-17) |

| 28-d mortality | 0 (0) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Obesity | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (20) |

| Hypertension | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 18 (51.4)* |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (22.9) |

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.6) |

| Heart disease‡ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.6) |

| Presenting symptoms | |||

| Cough | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 19 (73) |

| Fever | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 21 (81) |

| Dyspnea | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (85) |

| Headache | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (19) |

| Anosmia | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (27) |

| Laboratory findings on admission | |||

| Leukocytes, ×103/µL | — | — | 138.5 (101-190) |

| Lymphocytes, cells/µL | — | — | 1 136 (614-1 579) |

| Monocytes, cells/µL | — | — | 679.5 (489-890) |

| Platelet count, ×103/µL | — | — | 193 (153-263) |

| CRP, mg/dL§ | 0.11 (0.1-0.18) | 0.1 (0.1-0.11) | 15.2 (5.6-25.4)* |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL§ | 281 (236-312) | 229 (167-324) | 545 (375-582)* |

| D-dimer, ng/mL§ | 328 (227-456) | 192 (190-291) | 4 205 (2 319-14 179)* |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 9 (7-15) | 9 (7.75-9.25) | 39 (19- 86)* |

| Characteristics . | Control, n = 11 . | Mild/ asymptomatic, n = 6 . | Severe, n = 35 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53 (32-60) | 32 (30-34) | 57 (47-64) |

| Sex, male | 4 (28.6) | 2 (33.3) | 17 (48.6) |

| Respiratory support | |||

| Oxygen supplementation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (22.8) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (77.1) |

| SAPS 3 | 60 (47-68) | ||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | — | — | 150 (101-258) |

| Vasopressor | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (45.7) |

| Time from symptom onset to blood sample, d | — | 6 (1-12)† | 12 (8-17) |

| 28-d mortality | 0 (0) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Obesity | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (20) |

| Hypertension | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 18 (51.4)* |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (22.9) |

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.6) |

| Heart disease‡ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.6) |

| Presenting symptoms | |||

| Cough | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 19 (73) |

| Fever | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 21 (81) |

| Dyspnea | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (85) |

| Headache | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 5 (19) |

| Anosmia | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (27) |

| Laboratory findings on admission | |||

| Leukocytes, ×103/µL | — | — | 138.5 (101-190) |

| Lymphocytes, cells/µL | — | — | 1 136 (614-1 579) |

| Monocytes, cells/µL | — | — | 679.5 (489-890) |

| Platelet count, ×103/µL | — | — | 193 (153-263) |

| CRP, mg/dL§ | 0.11 (0.1-0.18) | 0.1 (0.1-0.11) | 15.2 (5.6-25.4)* |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL§ | 281 (236-312) | 229 (167-324) | 545 (375-582)* |

| D-dimer, ng/mL§ | 328 (227-456) | 192 (190-291) | 4 205 (2 319-14 179)* |

| IL-6, pg/mL | 9 (7-15) | 9 (7.75-9.25) | 39 (19- 86)* |

Numerical variables are represented as the median and the interquartile range, and qualitative variables are represented as the number and the percentage.

—, missing data; SAPS 3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score III.

P < .05 compared with control. The qualitative variables were compared using the 2-tailed Fisher exact test, and the numerical variables using the Student t test for parametric and the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric distributions.

Day of sample collection after the onset of symptoms was not computed for asymptomatic subjects.

Coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure.

Reference values of CRP (0.00-1.00), fibrinogen (238-498 mg/dL), and D-dimer (0-500 ng/mL).

All ICU-admitted patients received usual supportive care for severe COVID-19 and received respiratory support with either noninvasive oxygen supplementation (n = 8) or mechanical ventilation (n = 27) (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). Patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were managed with neuromuscular blockade and a protective ventilation strategy that included low tidal volume (6 mL/kg predicted body weight) and limited driving pressure (<16 cmH2O) as well as optimal positive end-expiratory pressure calculated based on the best lung compliance and PaO2/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio. In those with severe ARDS and PaO2/FiO2 ratio below 150 despite optimal ventilatory settings, prone position was initiated. Our management protocol included antithrombotic prophylaxis with 40 to 60 mg of enoxaparin per day. Patients did not receive routine steroids, antivirals, or other anti-inflammatory or antiplatelet drugs. The SARS-CoV-2− control participants were not under anti-inflammatory or antiplatelet drugs for at least 2 weeks.

All clinical information was prospectively collected using a standardized form: International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC)/World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Characterization Protocol for Severe Emerging Infections (CCP-BR).39 Clinical and laboratory data were recorded on admission in all severe patients included in the study, and the primary outcome analyzed was 28-day mortality (n = 18 survivors and 17 nonsurvivors; supplemental Table 2). Age and the frequency of comorbidities were not different between severe patients requiring mechanical ventilation or noninvasive oxygen supplementation or between survivors and nonsurvivors (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). The National Review Board of Brazil approved the study protocol (Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa [CONEP] 30650420.4.1001.0008), and informed consent was obtained from all participants or patients’ representatives.

Platelet and monocyte isolation

Blood samples were drawn into acid-citrate-dextrose and centrifuged (200g, 20 minutes, room temperature) to obtain the platelet-rich plasma (PRP). PRP was supplemented with 100 nM prostaglandin E1 (PGE1, Cayman 13010) and recentrifuged (500g, 20 minutes, room temperature) to pellet platelets. Platelets were resuspended in 2.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.4) containing 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% human serum albumin, and 100 nM PGE1, and incubated with anti-CD45 antibodies (1:200) for 10 minutes and magnetic bead conjugates (1:100) for an additional 15 minutes, followed by magnetic removal of leukocytes for 10 minutes (human CD45+ depletion kit; STEMCELL Technologies). Purified platelets were washed in 25 mL of pipes-saline-glucose (5 mM C8H18N2O6S2, 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 50 μM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2 × 6H2O, 5.5 mM glucose; pH 6.8) containing 100 nM PGE1, centrifuged again (500g, 20 minutes, room temperature) and resuspended in medium 199 (Lonza) to the concentration of 109 platelets per milliliter.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from whole blood after PRP was removed (bottom cell layer after the first centrifugation mentioned in this section) using Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) gradient centrifugation. The peripheral blood mononuclear cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1 mM EDTA and 2% fetal bovine serum to the concentration of 108 cells per milliliter and incubated with anti-CD14 antibodies (1:10) for 10 minutes (magnetic bead conjugates [1:20] were incubated for an additional 10 minutes), followed by magnetic recovery of monocytes for 5 minutes. Recovered monocytes were resuspended in PBS containing 1 mM EDTA and 2% fetal bovine serum and subjected to 2 more rounds of selection in the magnet according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Easy Sep human CD14+ selection kit; STEMCELL Technologies). The purity of monocyte preparations (>98% CD14+ cells) was confirmed through flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Isolated platelets were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-CD62P, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD63 and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD41, or PE-conjugated anti-TF and APC-conjugated anti-CD41 (all from BD Pharmingen) for 30 minutes at room temperature and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Platelet-monocyte aggregates were evaluated as previously described.20 Whole-blood samples were incubated for 10 minutes with fluorescence-activated cell sorter lysing buffer (BD Biosciences) and then centrifuged at 500g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and cells were resuspended in HT buffer (10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid [HEPES], 137 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 6H2O, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.4 mM Na2HPO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 0.35% bovine serum albumin [pH 7.4]). Monocytes were labeled with PE-conjugated anti-TF, peridinin-chlorophyll–conjugated CD14, and APC-conjugated anti-CD41 (BD Pharmingen) for 30 minutes at room temperature and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Platelets or monocytes labeled with each antibody separately were used for appropriate color compensation, and isotype-matched immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated with the same fluorochromes were used as the negative controls. A flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur) was used to acquire 10 000 CD41+ or 5000 CD14+ gated events and data were further analyzed using FlowJo software.

Fluorescence confocal microscopy

Platelets and leukocytes obtained after erythrocyte lysis as mentioned previously in “Materials and methods” were washed 1 more time with HT buffer and resuspended in PBS to a concentration of 3 × 105 leukocytes per milliliter. Cells (3 × 104) were adhered on gelatin-coated glass slides and stained with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated phalloidin (0.33 µM for 30 minutes) in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin for actin cytoskeleton labeling and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 0.2 μg/mL, 5 minutes) for nuclei. Images were acquired with an LSM 710 confocal microscope (ZEISS) and analyzed with ZEN 3.1 software (blue edition; ZEISS).

Quantification of inflammatory mediators in blood and airways

The concentration of proteins platelet factor 4 (PF4/CXCL4), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF; with 2 B subunits [PDGF-BB]), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and the eicosanoid thromboxane B2 (TXB2) was measured in plasma from patients or control volunteers, or tracheal aspirates from severe COVID-19 patients under mechanical ventilation, using standard commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems and Cayman Chemicals).

Platelet-monocyte ex vivo interaction

To examine whether platelets from COVID-19 patients modulate TF expression in monocytes from healthy volunteers, purified platelets and monocytes were incubated ex vivo at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Each experimental point contained 2 × 105 monocytes from a healthy volunteer and 2 × 107 platelets from a COVID-19 patient or a heterologous healthy volunteer. In selected experiments, platelet-monocyte interactions were performed in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against P-selectin (R&D Systems) or isotype-matched control (20 µg/mL), or with the clinically approved anti-integrin αIIbβ3 monoclonal antibody abciximab (50 µg/mL), aspirin (100 µM; Sigma-Aldrich), or clopidogrel (300 µM; Sigma-Aldrich). After 0.5, 2, or 18 hours of interaction, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and monocytes evaluated through flow cytometry as described previously in “Materials and methods.” The experiment was repeated using monocytes from 2 to 4 independent healthy volunteers with similar results, and representative data from 1 of the donors is shown.

Platelet stimulation with plasma from COVID-19 patients

To investigate whether soluble factors in plasma from COVID-19 patients contribute to platelet activation, platelets from healthy volunteers were incubated for 2 hours (37°C, 5% CO2 atmosphere) in plasma from 16 severe COVID-19 patients or 11 healthy volunteers. Platelet activation was assessed through flow cytometry as described previously in “Materials and methods.” The experiment was repeated using platelets from 3 independent healthy volunteers with similar results, and a representative data from 1 platelet donor is shown.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 7. All numerical variables were tested regarding their distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare differences among 3 groups following a normal (parametric) distribution, and the Tukey post hoc test was used to locate the differences between the groups. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed using the Student t test for parametric distributions or the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric distributions. Correlation coefficients were calculated using the Pearson correlation test for parametric distributions and the Spearman correlation test for nonparametric distributions.

Results

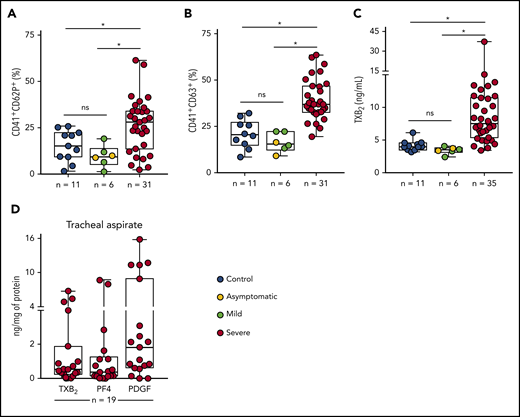

Increased platelet activation in patients with COVID-19

To assess platelet activation during SARS-CoV-2 infection, we evaluated the surface expression of CD62P (P-selectin) and CD63, markers of platelet α and dense granule secretion, respectively. As shown in Figure 1A-B, severe COVID-19 patients presented increased P-selectin and CD63 surface expression when compared with control participants and with asymptomatic/mildly ill infected subjects. Platelet activation was not increased in patients with mild COVID-19 or asymptomatic subjects compared with control volunteers (Figure 1A-B). We confirmed platelet activation in our cohort of severe COVID-19 patients by measuring plasma levels of TXB2, a metabolite from platelet TXA2 synthesis. Similar to platelet degranulation, TXA2 synthesis was increased in platelets from severe COVID-19 but not mild/asymptomatic subjects (Figure 1C). We then investigated whether activated platelets or products from platelet activation infiltrate to the airways of patients with severe COVID-19. We quantified the levels of TXB2 and the proteins from platelet α-granules PF4/CXCL4 and PDGF in tracheal aspirates from patients with COVID-19 under mechanical ventilation. As shown in Figure 1D, platelet-derived factors are present in tracheal aspirates from COVID-19 patients, suggesting that platelet activation and platelet-secretory products gain access to the airways in severe COVID-19 syndrome.

Increased platelet activation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. (A-B) The percentage of P-selectin (CD62P) (A) and CD63 (B) surface expression on platelets from SARS-CoV-2− control participants, SARS-CoV-2+ asymptomatic subjects, or symptomatic patients presenting mild to severe COVID-19 syndrome. (C) The concentration of TXB2 in plasma from control subjects or patients with COVID-19 presenting mild to severe syndrome. (D) Quantification of TXB2, PF4, and PDGF in tracheal aspirates from severe COVID-19 patients under mechanical ventilation (n = 19). The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups. ns, nonsignificant.

Increased platelet activation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. (A-B) The percentage of P-selectin (CD62P) (A) and CD63 (B) surface expression on platelets from SARS-CoV-2− control participants, SARS-CoV-2+ asymptomatic subjects, or symptomatic patients presenting mild to severe COVID-19 syndrome. (C) The concentration of TXB2 in plasma from control subjects or patients with COVID-19 presenting mild to severe syndrome. (D) Quantification of TXB2, PF4, and PDGF in tracheal aspirates from severe COVID-19 patients under mechanical ventilation (n = 19). The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups. ns, nonsignificant.

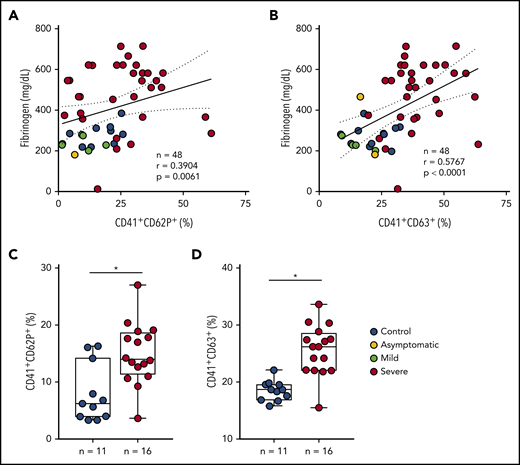

The inflammatory milieu of severe COVID-19 contributes to platelet activation

During severe COVID-19, immune dysregulation and cytokine storm may contribute to both hyperinflammation- and hypercoagulation-driven mortality.40-43 Patients with severe COVID-19 in the present study had increased levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimers, and fibrinogen in plasma (Table 1), evidencing systemic inflammation and activation of coagulation. Platelet activation was not correlated with IL-6 in COVID-19 (data not shown). Plasma levels of fibrinogen, on the other hand, positively correlated with platelet P-selectin and CD63 surface translocation (Figure 2A-B) and with the levels of TXB2 in circulation (r = 0.5892 and P = .0001) (supplemental Figure 1A). Platelet activation was also correlated with the levels of CRP (r = 0.4378 and P = .0021 for P-selectin, r = 0.7078 and P < .0001 for CD63, r = 0.6193 and P < .0001 for TXB2 in plasma) (supplemental Figure 1B-D). To gain insights on whether proinflammatory and procoagulant factors generated during COVID-19 are able to activate platelets, we stimulated platelets from healthy volunteers with plasma from severe COVID-19 ex vivo. As shown in Figure 2C-D, platelets incubated in plasma from patients exhibited increased P-selectin and CD63 surface translocation when compared with control subjects. These data indicate that circulating mediators are at least in part accountable for increased platelet activation in severe COVID-19.

Inflammatory mediators generated in severe COVID-19 contribute to platelet activation. (A-B) The percentage of P-selectin (CD62P) (A) and CD63 (B) expression on platelets was plotted against the concentration of fibrinogen in plasma. Linear regression and Spearman correlation were calculated according to the distribution of the dots. (C-D) Platelets from healthy volunteers were incubated with plasma from severe COVID-19 patients (severe, n = 16) or from SARS-CoV2− subjects (control, n = 11) for 2 hours. The percentages of P-selectin (C) and CD63 (D) are shown. All experiments were repeated with platelets from 3 independent healthy volunteers with similar results, and representative data from 1 of the platelet donors are shown. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups.

Inflammatory mediators generated in severe COVID-19 contribute to platelet activation. (A-B) The percentage of P-selectin (CD62P) (A) and CD63 (B) expression on platelets was plotted against the concentration of fibrinogen in plasma. Linear regression and Spearman correlation were calculated according to the distribution of the dots. (C-D) Platelets from healthy volunteers were incubated with plasma from severe COVID-19 patients (severe, n = 16) or from SARS-CoV2− subjects (control, n = 11) for 2 hours. The percentages of P-selectin (C) and CD63 (D) are shown. All experiments were repeated with platelets from 3 independent healthy volunteers with similar results, and representative data from 1 of the platelet donors are shown. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups.

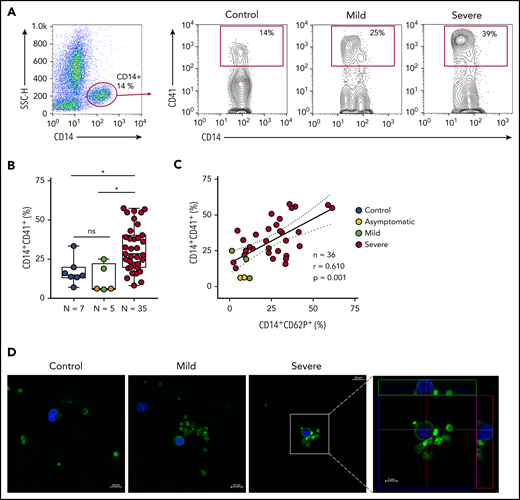

Platelets form aggregates with monocytes in severe COVID-19 patients

Platelet P-selectin is the main protein on activated platelets that mediates platelet adhesion and signaling to monocytes.19,20,44 We investigated whether activated platelets form aggregates with monocytes during SARS-CoV-2 infection. As shown in Figure 3A-B, COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU presented increased levels of platelet-monocyte aggregates when compared with control participants and to asymptomatic/mild infected subjects. Platelet P-selectin surface expression positively correlated with platelet-monocyte aggregate formation in infected subjects (Figure 3C). To visualize platelet-monocyte complexes formed in COVID-19 patients, platelets and leukocytes obtained from whole blood after lysis of erythrocytes were labeled with Alexa 488–phalloidin (F actin, green) and DAPI (nuclei, blue). As shown in Figure 3D, mononuclear cells (blue) in close interaction with F-actin–labeled platelets (green) were more often observed in severe COVID-19 patients than in control subjects or in patients with mild COVID-19 syndrome. The orthogonal projections of the confocal images from different planes provide further evidence that platelets from critically ill patients are interacting with the mononuclear cells.

Increased platelet-monocyte aggregates in severe COVID-19 patients. (A) Gating strategy for analysis of platelet-monocyte aggregates in patients with COVID-19 or control subjects. (B) Percentage of platelet-monocyte complexes (CD14+CD41+) among monocytes from SARS-CoV-2− control volunteers, SARS-CoV-2+ asymptomatic subjects, or symptomatic patients presenting mild to severe COVID-19 syndrome. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups. (C) The percentage of platelet P-selectin (CD62P) surface expression was plotted against the percentage of platelet-monocyte complexes in the same infected subjects. Linear regression and Pearson correlation were calculated according to the distribution of the dots. (D) Phalloidin-labeled cytospin blood samples from control subjects or COVID-19 patients. Platelets and leukocytes obtained from whole blood after lysis of erythrocytes were labeled with Alexa 488–phalloidin (F actin, green) and DAPI (nuclei, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm; inset, 5 μm. Representative images of platelet-monocyte aggregates are shown. The fourth panel shows orthogonal views from different planes of the confocal image. The green line generated a 2-dimensional (2D) image that is shown in the top green rectangle whereas the red line–generated 2D image is shown in the red rectangle on the right. SSC-H, side scatter height.

Increased platelet-monocyte aggregates in severe COVID-19 patients. (A) Gating strategy for analysis of platelet-monocyte aggregates in patients with COVID-19 or control subjects. (B) Percentage of platelet-monocyte complexes (CD14+CD41+) among monocytes from SARS-CoV-2− control volunteers, SARS-CoV-2+ asymptomatic subjects, or symptomatic patients presenting mild to severe COVID-19 syndrome. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups. (C) The percentage of platelet P-selectin (CD62P) surface expression was plotted against the percentage of platelet-monocyte complexes in the same infected subjects. Linear regression and Pearson correlation were calculated according to the distribution of the dots. (D) Phalloidin-labeled cytospin blood samples from control subjects or COVID-19 patients. Platelets and leukocytes obtained from whole blood after lysis of erythrocytes were labeled with Alexa 488–phalloidin (F actin, green) and DAPI (nuclei, blue). Scale bar, 10 μm; inset, 5 μm. Representative images of platelet-monocyte aggregates are shown. The fourth panel shows orthogonal views from different planes of the confocal image. The green line generated a 2-dimensional (2D) image that is shown in the top green rectangle whereas the red line–generated 2D image is shown in the red rectangle on the right. SSC-H, side scatter height.

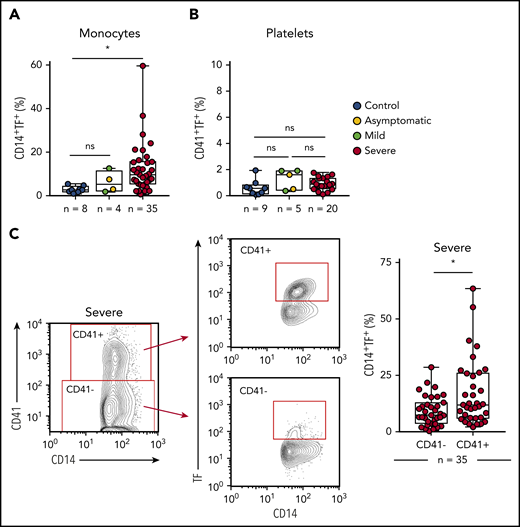

Platelet-monocyte aggregates have increased TF expression in COVID-19 patients

To better understand the role played by platelets and monocytes in the hypercoagulability state of COVID-19,3-5 we evaluated whether these cells express TF, the main trigger of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation.26 As shown in Figure 4A-B, we observed increased expression of TF in monocytes, but not in platelets, from critically ill COVID-19 patients when compared with SARS-CoV-2− controls. We then investigated the role of platelet-monocyte interaction to TF expression in COVID-19. We evaluated TF expression on monocytes that were tethered with platelets in severe COVID-19 patients compared with monocytes alone in the same sample. Importantly, monocyte TF expression was significantly higher within platelet-monocyte complexes (CD14+CD41+) when compared with monocytes without platelet adhesion (CD14+CD41−) (Figure 4C). This association was not driven by platelet TF expression because we did not observe any increase in TF expression in platelets from COVID-19 patients (Figure 4B). Importantly, plasma levels of D-dimers positively correlated with platelet activation (r = 0.4624 and P = .0009 for P-selectin, r = 0.6425 and P < .0001 for CD63, r = 0.5819 and P < .0001 for TXB2 in plasma) and monocyte TF expression (r = 0.4172 and P = .0039) (supplemental Figure 1E-H), suggesting possible participation in COVID-19–associated hypercoagulability.

Platelet-monocyte complexes express TF in severe COVID-19 patients. (A-B) The percentage of TF surface expression on monocytes (A) or platelets (B) from SARS-CoV2− control volunteers, SARS-Cov2+ asymptomatic subjects, or symptomatic patients presenting mild to severe COVID-19 syndrome. (C) The percentage of TF surface expression on monocytes that were complexed with platelets (CD14+CD41+) or circulating freely (CD14+CD41−) in severe COVID-19 patients. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups.

Platelet-monocyte complexes express TF in severe COVID-19 patients. (A-B) The percentage of TF surface expression on monocytes (A) or platelets (B) from SARS-CoV2− control volunteers, SARS-Cov2+ asymptomatic subjects, or symptomatic patients presenting mild to severe COVID-19 syndrome. (C) The percentage of TF surface expression on monocytes that were complexed with platelets (CD14+CD41+) or circulating freely (CD14+CD41−) in severe COVID-19 patients. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. *P < .05 between selected groups.

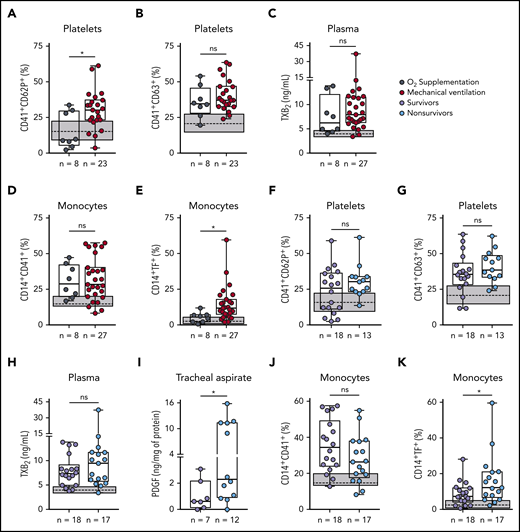

Platelet activation and monocyte TF expression associate with COVID-19 severity and mortality

Patients with severe COVID-19 were stratified based on their requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation (supplemental Table 1). Platelet P-selectin surface translocation and monocyte TF expression were significantly increased in mechanically ventilated patients as compared with those requiring noninvasive oxygen supplementation (Figure 5A,E). CD63 expression, TXA2 synthesis, and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation, on the other hand, were increased in severe COVID-19 patients regardless of mechanical ventilation (Figure 5B-D). We then investigated whether platelet activation at admission can predict ICU-related mortality in COVID-19 (supplemental Table 2). Although P-selectin surface expression was not different between survivors and nonsurvivors (Figure 5F), exhibiting P-selectin above the control group median was predictive of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 9.6 [95% confidence interval = 1.02-90.35]; P = .045). In addition, increased levels of PDGF-BB in the tracheal aspirates of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation and TF expression in monocytes were increased among nonsurvivors (Figure 5I,K). Platelet CD63 expression, TXA2 synthesis, and platelet-monocyte aggregates did not associate with mortality (Figure 5G,H,J). These data show that platelet activation in circulation and in the airways, as well as monocyte TF expression, associate with poor outcome in severe COVID-19 patients.

Increased platelet activation and TF expression by monocytes associate with severity and mortality in COVID-19. (A-E) Severe COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU were stratified between those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation or noninvasive O2 supplementation. The percentages of P-selectin (CD62P) (A) and CD63 (B) expression on platelets, the concentration of TXB2 in plasma (C), the percentage of monocytes forming aggregates with platelets (D), and TF expression on monocytes (E) are shown. (F-K) Severe COVID-19 patients were stratified according to the 28-day mortality outcome as survivors or nonsurvivors. The percentages of P-selectin (CD62P) (F) and CD63 (G) expression on platelets, the concentration of TXB2 in plasma (H), the quantification of PDGF-BB in tracheal aspirates (I), and the percentage of monocytes forming aggregates with platelets (J) and expressing TF (K) are shown. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. The gray box indicates the interquartile ranges and the dotted line represents the median of the SARS-CoV2− control group. *P < .05 between selected groups.

Increased platelet activation and TF expression by monocytes associate with severity and mortality in COVID-19. (A-E) Severe COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU were stratified between those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation or noninvasive O2 supplementation. The percentages of P-selectin (CD62P) (A) and CD63 (B) expression on platelets, the concentration of TXB2 in plasma (C), the percentage of monocytes forming aggregates with platelets (D), and TF expression on monocytes (E) are shown. (F-K) Severe COVID-19 patients were stratified according to the 28-day mortality outcome as survivors or nonsurvivors. The percentages of P-selectin (CD62P) (F) and CD63 (G) expression on platelets, the concentration of TXB2 in plasma (H), the quantification of PDGF-BB in tracheal aspirates (I), and the percentage of monocytes forming aggregates with platelets (J) and expressing TF (K) are shown. The horizontal lines in the box plots represent the median, the box edges represent the interquartile ranges, and the whiskers indicate the minimal and maximal value in each group. The gray box indicates the interquartile ranges and the dotted line represents the median of the SARS-CoV2− control group. *P < .05 between selected groups.

Platelet-monocyte interaction induces TF expression in COVID-19

Based on the association of monocyte TF expression with platelet-monocyte aggregates (Figure 4C), we hypothesized that platelet-monocyte interaction induces monocyte TF expression in severe COVID-19. To confirm this hypothesis, we incubated monocytes isolated from healthy volunteers with platelets from severe COVID-19 patients ex vivo and evaluated monocyte TF expression. We observed strong induction of TF expression on monocytes that were exposed to platelets from COVID-19 patients when compared with platelets from heterologous healthy volunteers (Figure 6A). TF expression was maximal at 2 hours of interaction, indicating that platelet-induced TF expression is a rapid event following platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation in COVID-19.

Platelets from COVID-19 patients induce TF expression in monocytes through mechanisms depending on P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3. (A) Monocytes from healthy volunteers were incubated with platelets from severe COVID-19 patients (COVID-19 platelets) or from heterologous healthy volunteers (control platelets) for the indicated time points. The percentage of TF-expressing monocytes is shown. (B-D) Control monocytes were exposed to platelets from severe COVID-19 patients for 2 hours in the presence of anti–P-selectin (anti-CD62P) neutralizing antibody, the anti-αIIb/β3 antibody abciximab, or isotype-matched IgG. The percentage of TF-expressing monocytes (B), platelet-monocyte complexes (C), and the percentage and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of P-selectin expression on CD14+CD41+ monocytes (D) are shown in each condition. (E-F) Control monocytes were exposed to platelets from COVID-19 patients for 2 hours in the presence of aspirin (100 µM) or clopidogrel (300 µM). Bars represent mean plus or minus standard error of the mean of monocytes exposed to platelets from 6 independent COVID-19 patients. All experiments were repeated with monocytes from 2 (B-D), 3 (E-F), or 4 (A) independent healthy volunteers with similar results, and representative data from 1 of the donors are shown. *P < .05 between selected groups.

Platelets from COVID-19 patients induce TF expression in monocytes through mechanisms depending on P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3. (A) Monocytes from healthy volunteers were incubated with platelets from severe COVID-19 patients (COVID-19 platelets) or from heterologous healthy volunteers (control platelets) for the indicated time points. The percentage of TF-expressing monocytes is shown. (B-D) Control monocytes were exposed to platelets from severe COVID-19 patients for 2 hours in the presence of anti–P-selectin (anti-CD62P) neutralizing antibody, the anti-αIIb/β3 antibody abciximab, or isotype-matched IgG. The percentage of TF-expressing monocytes (B), platelet-monocyte complexes (C), and the percentage and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of P-selectin expression on CD14+CD41+ monocytes (D) are shown in each condition. (E-F) Control monocytes were exposed to platelets from COVID-19 patients for 2 hours in the presence of aspirin (100 µM) or clopidogrel (300 µM). Bars represent mean plus or minus standard error of the mean of monocytes exposed to platelets from 6 independent COVID-19 patients. All experiments were repeated with monocytes from 2 (B-D), 3 (E-F), or 4 (A) independent healthy volunteers with similar results, and representative data from 1 of the donors are shown. *P < .05 between selected groups.

Platelets from patients with COVID-19 induce monocyte TF expression through mechanisms depending on P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3

P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3 play major roles in platelet-leukocyte interaction and platelet-mediated reprogramming of leukocyte responses, including monocyte TF expression.14,16,23,24,45 To better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying platelet-induced TF expression by monocytes in COVID-19, we performed ex vivo platelet-monocyte coculture for 2 hours in the presence of an anti–P-selectin neutralizing antibody or the clinically approved anti-αIIb/β3 monoclonal antibody abciximab. As shown in Figure 6B, both anti–P-selectin and abciximab were able to prevent platelets from COVID-19 patients to induce TF expression in monocytes. Interestingly, only P-selectin, but not αIIb/β3, neutralization was able to reduce platelet-monocyte aggregate formation ex vivo (Figure 6C), indicating that P-selectin is the main adhesion molecule on platelets from COVID-19 patients that mediates interaction with monocytes. Because integrin αIIb/β3 is also known to mediate platelet-platelet aggregate formation and amplify platelet activation signaling,46 we investigated whether abciximab prevents TF expression by inhibiting further platelet activation during platelet-monocyte interactions. However, abciximab pretreatment did not affect P-selectin expression on platelets from COVID-19 patients that were aggregated with monocytes ex vivo (Figure 6D). Of note, the antiplatelet agents aspirin or clopidogrel failed to modify platelet-monocyte aggregate formation or platelet-induced TF expression in monocytes ex vivo (Figure 6E-F). Collectively, these data indicate that monocyte TF expression in COVID-19 depends on P-selectin–mediated adhesion and platelet-monocyte signaling through P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3.

Discussion

As knowledge of severe COVID-19 evolves, hypercoagulability emerges as a central pathological feature and clinical complication. Thrombotic events are particularly frequent in critically ill COVID-19 patients, with increased incidence of venous and arterial thromboembolism, and even life-threatening complications such as pulmonary embolism, ischemic stroke, and myocardial infarction.4,5 Increased alveolar microthrombi and higher frequencies of disseminated intravascular coagulation are observed among COVID-19 deaths compared with bacterial, SARS, or influenza pneumonia.3,6,47-51 In autopsy studies, small thrombi were observed in pulmonary arterioles in areas of disrupted alveolar-capillary integrity.51,52 We show that increased platelet activation and platelet-dependent TF expression in monocytes at admission predicts patients’ poor outcomes, including the requirement of mechanical ventilation and in-hospital mortality.

Increased platelet activation and platelet-monocyte aggregate formation were present in severe COVID-19 patients, but not in patients with mild self-limiting COVID-19 syndrome. Our data show that aggregation with activated platelets has a major impact on TF expression by monocytes during COVID-19. Similar results have been observed in patients with acute coronary syndrome, a life-threatening thrombotic complication of atherosclerosis.53 Both platelets and monocytes have been shown to express TF under procoagulant or proinflammatory stimuli.54-58 In bacterial sepsis, a syndrome with many parallels with severe COVID-19,59 TF messenger RNA translation confers platelet procoagulant activity.56 TF expression has been also observed in platelets and monocytes from HIV-infected subjects, and plays a major role in HIV-associated coagulopathy.58,60 In our cohort of severe COVID-19, TF expression was not increased in platelets, suggesting that higher TF expression in platelet-monocyte aggregates derived from activated monocytes. As proof of principle, ex vivo platelet-monocyte interactions confirmed the ability of platelets from COVID-19 patients to induce monocyte TF expression.

Previous studies have shown the ability of activated platelets to induce TF expression in monocytes.24,25,61,62 Platelets and monocytes under different stimuli present distinct pathways of TF expression.24,61,62 We investigated the molecular interactions mediating platelet-induced monocyte TF expression in COVID-19. To that end, we used an anti–P-selectin neutralizing antibody and the anti-integrin αIIb/β3 monoclonal antibody abciximab, a clinically approved antiaggregation drug. Although P-selectin was the main adhesion molecule mediating platelet-monocyte aggregate formation in this model, both P-selectin and integrin αIIb/β3 signaling were required for platelet-induced TF expression. Interestingly, abciximab prevented TF expression by directly interrupting integrin signaling to the monocyte because platelet activation was not affected by integrin αIIb/β3 blocking during the coculture. Pretreatment with aspirin and clopidogrel did not prevent platelet-induced TF in monocytes. However, because these drugs were delivered ex vivo to platelets that were already activated in patients, it may not reflect the effects of antiplatelet therapy in vivo. Platelet activation and platelet-monocyte interactions in COVID-19 patients under antiplatelet therapy, as well as in patients presenting (or not) thromboembolic complications, are important issues to be addressed in the future. Our data indicate that platelet-monocyte interaction in COVID-19 is a complex phenomenon depending on at least 2 signals for platelet-induced reprograming of monocyte responses.

Although the mechanisms underlying platelet activation in COVID-19 remain unknown, our data show that inflammatory and/or procoagulant mediators in COVID-19 patients may contribute to platelet activation. These data are consistent with the notion that intense cytokine production may trigger hyperinflammation and hypercoagulability.43 Proinflammatory cytokines and procoagulant factors such as thrombin may also contribute to TF expression in monocytes,60 even though TF expression was strongly associated with platelet-monocyte interaction in our cohort of severe COVID-19. Platelets are also known to modulate monocyte secretion of cytokines and chemokines.19,20,63 We have previously shown that platelet monocyte interactions change the monocyte cytokine profile during dengue infection toward a proinflammatory pattern.20 Similar results have been reported for platelet-monocyte interactions in peripheral artery disease and aging,63,64 although different mechanisms are involved in platelet-monocyte interactions during sterile or infection-driven inflammation.20,63,64 New studies are still necessary to determine how systemic inflammation contribute to platelet activation in COVID-19 and whether activated platelets amplify inflammation and hypercoagulability in these patients.

In summary, we describe novel mechanisms of activation-dependent platelet-induced TF expression in monocytes during COVID-19 that were associated with severity and mortality in a cohort of ICU-admitted severe COVID-19 patients. Considering the growing body of evidence showing hypercoagulability as a pathologic feature in COVID-19 ARDS, each of these molecular events and cellular interactions potentially contributes to COVID-19 pathogenesis. New studies are still necessary to address the potential implications of platelet-monocyte interactions and TF activity as therapeutic targets in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

For original data, please contact the corresponding authors.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Guy A. Zimmerman, Matthew T. Rondina, and Alda Bozza for insightful discussions and comments on the work and the manuscript; the multiuser facility on multiplex analysis and the confocal imaging facility from the Rede de Plataformas Tecnológicas FIOCRUZ; and Edson F. Assis and Pedro Paulo Manso for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Inova FIOCRUZ (P.T.B., F.A.B., T.M.L.S., E.D.H.).

Authorship

Contribution: E.D.H. performed experimental design and executed the majority of the experiments, data analyses, and manuscript writing; I.G.A.-Q., L.P., L.T., and E.A.B. performed part of the experiments and data analysis; C.R.R.P. performed molecular diagnostics of patients and control subjects through RT-PCR; P.K. and C.R. performed patient inclusion and clinical management duties; P.K., C.R., and S.F. performed clinical and laboratorial data compilation and patient classification; T.M.L.S. and F.A.B. performed experimental design and manuscript review; P.T.B. performed experimental design and manuscript review and directed all aspects of the study; and all authors reviewed and critically edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Patrícia T. Bozza, Institute Oswaldo Cruz, Av Brasil 4365–Pav 108 Sala 47, Rio de Janeiro, 21040900 Brazil; e-mail: pbozza@ioc.fiocruz.br or pbozza@gmail.com; or Eugenio D. Hottz, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora - Departamento de Bioquímica/ICB, Rua José Lourenço Kelmer, s/n, campus universitário, São Pedro, Juiz de Fora MG 36036-330, Brazil; e-mail: eugenio.hottz@icb.ufjf.br or eugeniohottz@gmail.com.