In this issue of Blood, Rocca et al show that aspirin insensitivity or incomplete platelet inhibition with standard once-per-day low-dose aspirin in patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) is overcome by twice-per-day dosing of low-dose aspirin without an increase in adverse effects. This presents an attractive strategy for improving vascular outcomes in ET.1

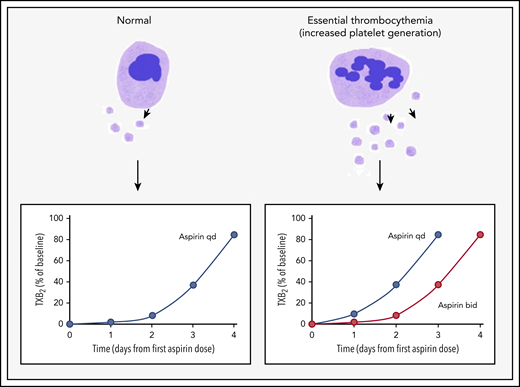

Accelerated platelet generation leads to shorter duration of aspirin effect and aspirin insensitivity in ET. In healthy individuals, suppression of serum TXB2 levels (a marker of platelet activation) in response to a single dose of aspirin lasts for ∼3 days. However, platelet generation is increased in ET, which results in accelerated renewal of COX-1, the target for aspirin. Thus TXB2 levels recover more rapidly. This effect can be overcome by shortening the dosing interval to once every 12 hours. bid, twice per day; qd, once per day.

Accelerated platelet generation leads to shorter duration of aspirin effect and aspirin insensitivity in ET. In healthy individuals, suppression of serum TXB2 levels (a marker of platelet activation) in response to a single dose of aspirin lasts for ∼3 days. However, platelet generation is increased in ET, which results in accelerated renewal of COX-1, the target for aspirin. Thus TXB2 levels recover more rapidly. This effect can be overcome by shortening the dosing interval to once every 12 hours. bid, twice per day; qd, once per day.

Thrombosis, particularly arterial thrombosis, is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in ET. Patients with the JAK2 V617F mutation, older individuals, and those with other cardiovascular risk factors are at particularly high risk. Low-dose aspirin is the cornerstone of thromboprophylaxis in ET, and cytoreductive therapy is recommended for those with higher risk disease.2 However, there are no randomized trials showing that aspirin reduced vascular events in ET, and benefit is indirectly inferred from observational data and a single randomized trial that showed reduced thrombotic events in patients with polycythemia vera who received aspirin.3 The lifetime rate of thrombosis in ET is ∼60%; however, the risk varies widely between low-risk and high-risk patients. As an example, annual risk of thrombosis is <2% in patients who are younger than age 60 years with no history of thrombosis4 compared with an annual recurrence rate of 6% to 8% among patients, even those receiving antiplatelet therapy, who have already had a thrombotic event.5 A recent systematic review that included 18 observational studies with more than 6000 individuals with ET concluded that the benefit of aspirin in ET is questionable. The authors estimated a very modest median risk reduction of 26%, which is lower than that seen in polycythemia vera3 or patients without myeloproliferative neoplasms. In this landscape, there is a critical need to improve antithrombotic strategies for patients with ET, and novel approaches such as low-dose anticoagulation with apixaban (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04243122) and different aspirin regimens are being evaluated.

Enhanced platelet activation is a characteristic feature of ET, and several groups have demonstrated elevated levels of thromboxane B2 (TXB2) generation and increased urinary excretion of thromboxane metabolites, which are stable and validated markers of platelet activation. Platelet production is frequently enhanced several-fold in myeloproliferative disorders, and this has been proposed as a major mechanism underlying aspirin resistance in ET (see figure). Aspirin exerts its antithrombotic and cardioprotective effects by irreversibly inhibiting platelet cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) and blocking TXA2 biosynthesis.6 Despite its short plasma half-life (∼10-20 minutes), the biological effects of aspirin last several days because of the time required for megakaryocytes to provide a new pool of fresh aspirin-naive platelets.6 In fact, only about 10% of the platelet pool is replaced every 24 hours in healthy individuals who take low-dose aspirin once per day with almost complete suppression of serum TXB2 levels that take ∼3 days to recover6 ; however, this is less effective in patients with ET.7 Pascale et al8 showed that the immature platelet fraction independently predicted serum TXB2, which suggests that accelerated renewal of platelets led to a shorter duration of aspirin effect. In support of this hypothesis, they found that increasing dosing frequency to twice per day improved TXB2 reduction significantly, whereas doubling the aspirin dose without increasing frequency of dosing did not have the same effect. The more critical question is whether improved suppression of thromboxane synthesis translates into clinical benefit. Indirect evidence comes from a study by Eikelboom et al9 who demonstrated that aspirin-resistant thromboxane production was associated with a several-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death in a cohort of patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. However, benefit needs to be demonstrated in robust clinical trials.

This initial report from the randomized, double-blind Aspirin Regimens in Essential Thrombocythemia (ARES) study is an important first step in this direction. The dose finding component of the study evaluated aspirin 100 mg given 1, 2 or 3 times per day for 2 weeks. Twice-per-day dosing significantly reduced serum TXB2 levels (there was interindividual variability in these levels) and reduced TXA2-dependent platelet activation in vivo without an increase in gastrointestinal adverse effects. Three-times-per-day dosing had a similar effect on platelet activation markers but led to increased gastrointestinal disturbances. Urinary prostacyclin metabolite, a surrogate marker for endothelial prostacyclin production and vascular safety, was not significantly reduced with either experimental regimen. A reduction in microvascular disturbances such as erythromelalgia was not noted. On the basis of these results, the long-term phase of the ARES study will evaluate aspirin 100 mg dosed once per day vs twice per day to answer the more pressing questions of whether shorter dosing intervals will have a meaningful impact on clinical end points, including thrombotic events and cardiovascular mortality. Cytoreduction is currently recommended for high-risk patients with ET, and it has a greater effect on reducing thrombotic events than antiplatelet therapy alone.2 Hopefully, subgroup analyses will address the incremental benefit of frequent aspirin dosing in patients already receiving cytoreductive therapy, which may attenuate aspirin resistance by suppressing platelet turnover.

Major bleeding is the most significant complication of aspirin therapy, and even low-dose once-per-day aspirin increased the rate of major bleeding by nearly 1.5-fold.10 The concern that more frequent dosing may increase bleeding is especially relevant for ET patients with platelet counts over one million/μL who are at risk for acquired von Willebrand disease and abnormal bleeding.2 An increase in bleeding events or gastrointestinal disturbances was not noted with twice-per-day dosing over 2 weeks of treatment in the Rocca et al study, although evaluation of safety and tolerability over longer periods of use are needed before these regimens can be recommended. Ideally, future studies will develop risk-adapted antithrombotic strategies that incorporate clinical and molecular predictors of thrombosis and bleeding as well as markers of platelet turnover and activation to provide truly personalized therapy.

The evidence in support of multiple daily doses of aspirin to suppress TX synthesis within 2 weeks of therapy in ET is compelling. Future results from the ARES trial will hopefully provide definitive guidance on whether overcoming biochemical evidence of aspirin resistance improves clinical outcomes. If the results are positive, they have the potential to replace the empiric, one-size-fits-all approach to antithrombotic therapy in ET.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal