Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) remains the only potentially curative therapy for myelofibrosis (MF). However, despite improvements in donor availability, most patients receive non-HCT therapy in the form of conventional drugs (e.g. hydroxyurea), or more recently, JAK inhibitor therapy (JAKi). For a proportion of patients, JAKi offers durable clinical benefit in the form of symptom improvement, reduction in splenomegaly and improved quality of life. The role of HCT in the JAKi era has not been well studied, and despite recent advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis and refinement of prognostic scoring systems,real-world decision making remains challenging. The goal of this study was to compare the outcomes of patients who received upfront JAKi vs. HCT for MF in dynamic international prognostic scoring system (DIPSS)-stratified categories.

Methods

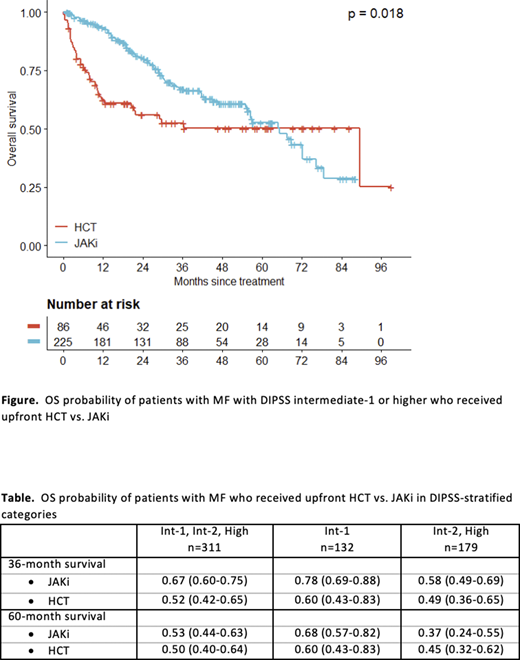

This multicentre study included adult patients up to age 70 years with primary or secondary MF in chronic phase who were first seen at one of the eight participating centres in Canada and the United States between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2017. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS) in patients with DIPSS int-1 risk or higher who received JAKi vs. HCT.

To compare the planned, upfront treatment strategy, patients who received a short-course of JAKi as bridging therapy prior to HCT (< 6 months or documented plan of care) were analysed in the HCT group. Similarly, patients who were treated with JAKi, but received a HCT following JAKi failure (>12 months or documented progression) were analysed in the JAKi group.

To minimize selection and lead-time bias, OS was calculated from the start of JAKi and date of transplant, respectively. Patients who were transplanted for accelerated- or blast-phase disease were not included in the analysis. OS was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences were tested using the log-rank test.

Results

Between 2012 and 2017, 506 patients with MF were seen at the study centres and 311 received JAKi or HCT. Of these, 174 (56%) had PMF and 137 (44%) had post-ET or post-PV MF. An upfront HCT strategy was used in 86 patients and an upfront JAKi strategy was used in 225 patients. Of those, 53 patients went on to receive HCT following JAKi failure. The median duration of follow up of survivors was 32.8 (1.2 - 99.2) months.

The median OS of MF patients with DIPSS int-1 or higher was 65.3 (95% CI: 55.7 - 76.4) months for patients treated with an upfront JAKi strategy and 89.4 (95% CI: 20.4 - not reached) months for those treated with an upfront HCT strategy (p=0.018, Figure).

The survival of patients with int-1 risk disease was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.69 - 0.88) in the JAKi group vs. 0.60 (95% CI: 0.43 - 0.83) in the HCT group at 36 months and 0.68 (95% CI: 0.57-0.82) in the JAKi group vs. 0.60 (95% CI: 0.43-0.83) in the HCT group at 60 months. Given the small number of patients with DIPSS high risk, these patients were combined with the int-2 cohort for analysis. The survival of patients with int-2/high risk disease was 0.58 (95% CI: 0.49 - 0.69) in the JAKi group vs. 0.49 (95% CI: 0.36 - 0.65) in the HCT group at 36 months and 0.37 (95% CI: 0.24-0.55) in the JAKi group vs. 0.45 (95% CI: 0.32-0.62) in the HCT group at 60 months (Table).

Conclusions

Previous studies, which included many patients treated in the era before widespread availability of JAKi, supported an upfront HCT strategy in patients with higher risk MF. While these agents have not demonstrated consistent disease-modifying effects, many patients do experience durable clinical benefit in the form of symptom improvement and reduction in spleen size. In our study, there was no clear benefit of upfront HCT. The median OS of patients who received HCT upfront was longer than that of patients who were treated with upfront JAKi, but upfront HCT was associated with early mortality and the OS benefit was not apparent until after 5 years.

An inherent limitation of this study is a lack of data on potentially important comorbid conditions which may have contributed to selection bias. However, to our knowledge this is the largest study to compare upfront HCT and JAKi strategies in patients with higher risk MF, making these findings relevant to modern clinical practice in the JAKi era. A delayed transplant approach may be appropriate for selected patients who are deriving clinical benefit from JAKi. Defining the optimal timing for HCT in higher risk MF remains a question for future research.

Maze:Pfizer: Consultancy; Novartis: Honoraria; Takeda: Research Funding. Arcasoy:CTI Biopharma: Research Funding; Samus Therapeutics: Research Funding; Gilead: Research Funding; Incyte: Research Funding; Janssen: Research Funding. Yacoub:Dynavax: Current equity holder in publicly-traded company; Ardelyx: Current equity holder in publicly-traded company; Cara Therapeutics: Current equity holder in publicly-traded company; Hylapharm: Current equity holder in private company; Incyte: Speakers Bureau; Agios: Honoraria, Speakers Bureau; Novartis: Speakers Bureau; Roche: Other: Support of parent study and funding of editorial support. McNamara:Novartis: Honoraria. Foltz:Celgene: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Constellation: Research Funding; Incyte: Research Funding; Novartis: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Gupta:Novartis: Consultancy, Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees, Research Funding; Bristol MyersSquibb: Honoraria, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Sierra Oncology: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Pfizer: Consultancy; Incyte: Honoraria, Research Funding.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal