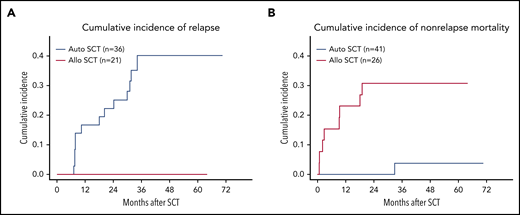

The predominant cause of failure with auto-SCT is relapse compared to nonrelapse mortality with allo-SCT for PTCL. See Figure 3A-B in the article by Schmitz et al that begins on page 2646.

The predominant cause of failure with auto-SCT is relapse compared to nonrelapse mortality with allo-SCT for PTCL. See Figure 3A-B in the article by Schmitz et al that begins on page 2646.

In this issue of Blood, Schmitz et al randomized 104 patients with high-risk nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) following an anthracycline-based induction regimen to receive either an autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT) or an allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT) as consolidation.1 With a median follow-up of 42 months, the study found the 3-year event-free survival (EFS) was 43% for allo-SCT and 38% for auto-SCT (P = .583), and the 3-year overall survival (OS) was 57% for allo-SCT and 70% for auto-SCT (P = .408).

Several important issues are highlighted in this study. Only 65% of the patients who enrolled could go on to receive the assigned transplant consolidation mostly because of early progression of the PTCL, toxicities, or other logistical issues. The best chance we have to get the PTCL patients into a good remission is with the induction therapy, allowing patients to go on to the consolidation transplant. For younger transplant-eligible patients, typically a cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, oncovin, etoposide, and prednisone (CHOEP)-based regimen, or more recently if the PTCL is CD30+, a brentuximab vedotine (BV)–cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone (CHP) regimen is often the first choice.2,3 Newer agents and regimens that are more active against PTCL may improve this initial complete remission rate. Although untested in a randomized study, the addition of BV to front-line treatment may be a first step to getting more patients to transplantation with a suggestion of an improved outcome.4

Another important outcome from this study was the similar EFS and OS for those patients randomized to auto-SCT vs allo-SCT. However, the pattern of failure was quite different, with the auto-SCT patients having a much higher relapse rate and the allo-SCT patients having a much higher nonrelapse mortality, mostly associated with graft- versus- host disease and infections (see figure). To improve the number of patients able to go on to a consolidation auto-SCT and therefore the overall results, adding novel agents used for relapsed PTCL treatment to the frontline treatment has been evaluated.5,6 Many of these trials demonstrated increased toxicity without the benefit of improved remissions. However, the 1 randomized trial that has been positive so far has been the addition of BV to CHP for selected CDD30+ PTCL patients.3 In the auto-SCT patients, better induction chemotherapy, transplant regimens, and/or posttransplant maintenance (such as BV used after transplant for higher risk Hodgkin lymphoma) may be a path for improving outcomes in a subset of patients.7

For allo-SCT, reduction of GVHD and/or infections with alternative regimens, cell sources, or newer immunosuppressive agents could alter this balance.8,9 Although the allo-SCT arm demonstrated a strong graft-versus-lymphoma effect in PTCL patients, the higher toxicities and added cost of this type of transplant currently do not justify its use in most PTCL patients in first remission. Standard chemotherapy followed by auto-SCT remains the preferred option for younger patients with PTCL. Improvements in induction chemotherapy, transplant regimens, supportive care, and possibly posttransplant maintenance should continue to be investigated in future clinical trials. The use of allo-SCT can remain an option for patients who relapse after auto-SCT in first remission with some patients deriving long-term benefit.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research/grant support from Astra-Zeneca, Incyte Corp, Kite Pharma, Novartis, Seattle Genetics, Loxo, and Epizyme and has received consultancy fees/honorarium from Abbvie, Epizyme, Vandiam Group, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, Kite Pharma, Astra-Zeneca, Verastem, Miltenyi, Loxo, Allogene, Wugene, Celgene, Roche, Genentech, Karyopharm, and Morphosis.