Abstract

The bone marrow (BM) is responsible for generating and maintaining lifelong output of blood and immune cells. In addition to its key hematopoietic function, the BM acts as an important lymphoid organ, hosting a large variety of mature lymphocyte populations, including B cells, T cells, natural killer T cells, and innate lymphoid cells. Many of these cell types are thought to visit the BM only transiently, but for others, like plasma cells and memory T cells, the BM provides supportive niches that promote their long-term survival. Interestingly, accumulating evidence points toward an important role for mature lymphocytes in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and hematopoiesis in health and disease. In this review, we describe the diversity, migration, localization, and function of mature lymphocyte populations in murine and human BM, focusing on their role in immunity and hematopoiesis. We also address how various BM lymphocyte subsets contribute to the development of aplastic anemia and immune thrombocytopenia, illustrating the complexity of these BM disorders and the underlying similarities and differences in their disease pathophysiology. Finally, we summarize the interactions between mature lymphocytes and BM resident cells in HSC transplantation and graft-versus-host disease. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which mature lymphocyte populations regulate BM function will likely improve future therapies for patients with benign and malignant hematologic disorders.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in specialized bone marrow (BM) niches that regulate their maintenance to ensure lifelong blood cell production. Numerous cell types contribute to the formation and function of such niches, which exist in various compositions and locations and support diverse functional states of HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors. Niches provide anchorage and survival signals, regulate HSC quiescence, self-renewal, differentiation, proliferation, homing, and mobilization, and modulate BM output.1 Sinusoidal endothelial cells and perivascular C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)-abundant reticular (CAR) cells are important constituents of HSC niches, but they also constitute a topologically complex network to which many other BM cells connect2,3 (Figure 1). In addition to classical niche cells that have been identified, it has become clear that mature hematopoietic cells also regulate hematopoiesis through various mechanisms. Lymphocytes are of particular interest, because their motile behavior and dedicated role in immunity enables them to transfer information from the periphery back to the BM. Many mature lymphocyte subsets can enter the BM, and an attractive hypothesis is that these cells provide feedback about an ongoing infection, which enables a tailored hematopoietic response against the invading pathogen. Resting BM T cells already produce HSC-supportive cytokines,4,5 whereas their transient activation boosts the production of cytokines that skew hematopoietic differentiation.6 However, prolonged T-cell activation suppresses hematopoiesis, causing the development of BM failure diseases such as aplastic anemia (AA) by impairing HSC maintenance.7

Localization and function of mature lymphocytes in the BM. Sinusoidal endothelial cells and perivascular C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)-abundant reticular (CAR) cells are important constituents of HSC niches and form a topologically complex network to which many other BM cells connect. (A) Plasmablasts (PB) colocalize with perisinusoidal CAR cells. Here, they receive important survival signals such as B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), which enable them to differentiate into long-lived immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells (PCs). Plasma cells are closely associated with BM regulatory T cells (TREGS), dendritic cells (DCs), and eosinophils (Eos). During various clinical conditions, the BM can contain germinal centers, complete with follicular DCs (FDCs) and T follicular helper (TFH) cells. The BM contains significant numbers of memory B cells (BMEM), the majority of which are noncirculating BM resident cells that dock onto VCAM-1+ stromal cells. (B) Scattered naïve CD8+ T cells (CD8+ Tnaïve) cluster at a 10:1 ratio around antigen-presenting cells (APCs) presenting their cognate antigen. Both naïve and memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TMEM) locate close to the sinusoidal vessel and perivascular VCAM-1+ stromal cells that support their survival and maintenance by producing IL-7 and IL-15. Memory CD8+ T cells produce tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which can regulate or disrupt HSC maintenance, depending on the amount produced. Memory CD4+ T cells (CD4+ TMEM) colocalize with VCAM-1+ stromal cells, which also produce IL-7. They secrete cytokines necessary for HSC maintenance, such as IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Tregs preserve normal hematopoiesis because of their T-cell suppressive function and possibly because of their IL-10 secretion. CD150hi Tregs and CD4+ T cells localize near HSCs in the perivascular niche and provide immune privilege. Extracellular adenosine generated via CD39 expressed on those lymphocyte subsets maintains HSC quiescence. (C-D) The BM also contains mature γδ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NK T cells (NKT cells), and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), but little is known about their precise localizations and functions. (C) BM NKT cells can be activated by CD1d-expressing HSCs and enhance myelopoiesis by secreting GM-CSF. BM NKT cells also secrete IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4, suggesting that they regulate hematopoiesis. Whether γδ T cells regulate hematopoiesis, as has been shown for αβ T cells, is not known. (D) The presence of ILC2s and ILC3s in the BM has been reported for mice and humans, respectively. ILC3s in human BM may be harbored in a stromal cell niche, but systematic analyses of the presence, localization, and function of mature ILCs in the BM are still lacking. In humans and mice, BM NK cells are a major source of cytokines that can regulate hematopoiesis, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and GM-CSF. In a mouse Toxoplasma gondii infection model, BM NK cells triggered by systemic IL-12 produced IFN-γ, promoting an immune regulatory program in monocytes (Mono).

Localization and function of mature lymphocytes in the BM. Sinusoidal endothelial cells and perivascular C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)-abundant reticular (CAR) cells are important constituents of HSC niches and form a topologically complex network to which many other BM cells connect. (A) Plasmablasts (PB) colocalize with perisinusoidal CAR cells. Here, they receive important survival signals such as B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), which enable them to differentiate into long-lived immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells (PCs). Plasma cells are closely associated with BM regulatory T cells (TREGS), dendritic cells (DCs), and eosinophils (Eos). During various clinical conditions, the BM can contain germinal centers, complete with follicular DCs (FDCs) and T follicular helper (TFH) cells. The BM contains significant numbers of memory B cells (BMEM), the majority of which are noncirculating BM resident cells that dock onto VCAM-1+ stromal cells. (B) Scattered naïve CD8+ T cells (CD8+ Tnaïve) cluster at a 10:1 ratio around antigen-presenting cells (APCs) presenting their cognate antigen. Both naïve and memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TMEM) locate close to the sinusoidal vessel and perivascular VCAM-1+ stromal cells that support their survival and maintenance by producing IL-7 and IL-15. Memory CD8+ T cells produce tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which can regulate or disrupt HSC maintenance, depending on the amount produced. Memory CD4+ T cells (CD4+ TMEM) colocalize with VCAM-1+ stromal cells, which also produce IL-7. They secrete cytokines necessary for HSC maintenance, such as IL-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Tregs preserve normal hematopoiesis because of their T-cell suppressive function and possibly because of their IL-10 secretion. CD150hi Tregs and CD4+ T cells localize near HSCs in the perivascular niche and provide immune privilege. Extracellular adenosine generated via CD39 expressed on those lymphocyte subsets maintains HSC quiescence. (C-D) The BM also contains mature γδ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NK T cells (NKT cells), and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), but little is known about their precise localizations and functions. (C) BM NKT cells can be activated by CD1d-expressing HSCs and enhance myelopoiesis by secreting GM-CSF. BM NKT cells also secrete IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4, suggesting that they regulate hematopoiesis. Whether γδ T cells regulate hematopoiesis, as has been shown for αβ T cells, is not known. (D) The presence of ILC2s and ILC3s in the BM has been reported for mice and humans, respectively. ILC3s in human BM may be harbored in a stromal cell niche, but systematic analyses of the presence, localization, and function of mature ILCs in the BM are still lacking. In humans and mice, BM NK cells are a major source of cytokines that can regulate hematopoiesis, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and GM-CSF. In a mouse Toxoplasma gondii infection model, BM NK cells triggered by systemic IL-12 produced IFN-γ, promoting an immune regulatory program in monocytes (Mono).

Here, we discuss the diversity, localization, and (patho)physiology of mature lymphocyte populations in the BM (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). We focus on B cells, T cells, and innate lymphoid cell (ILC) populations and address their roles in homeostasis, upon immune challenge, and in non-neoplastic hematologic disorders, including AA, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), HSC transplantation (HSCT), and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The role of lymphocytes in hematologic malignancies and antitumor therapies is important, but it has been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere8,9 and will not be covered here.

Localization and function of mature lymphocytes in the BM

B cells and plasma cells

The BM acts as a primary lymphoid organ by accommodating B-cell development, and it also harbors the most differentiated B cells, the plasma cells. Long-lived plasma cells are the first and best described mature lymphocyte subset residing in the BM, and their accumulation makes the BM a major site of antibody production.10 Plasmablasts (plasma cell precursors that develop during a humoral immune response in secondary lymphoid tissues [SLTs]) express C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) and CXCR4 and home to the BM via endothelial cells expressing CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL12.11 Upon BM entry, plasmablasts co-localize with CAR cells, where they receive important survival signals, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS), and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), which enable their differentiation into long-lived plasma cells12-14 (Figure 1A). This process is important for long-term immunity after infection and vaccination and also for the pathophysiology of multiple myeloma.15 Interestingly, although plasma cells and HSCs are both highly responsive to CXCL12 and therefore reside close to CAR cells,16 there is, to our knowledge, no evidence for functional crosstalk between plasma cells and HSCs. In contrast, plasma cells are closely associated with BM regulatory T cells (Tregs), dendritic cells (DCs), and eosinophils, and depletion of Tregs significantly reduces BM plasma cell numbers17,18 (Figure 1A).

As with SLTs, B-cell activation and differentiation can also occur inside the BM.19 Microscopic analyses in autoimmune disorders, infections, lymphomas, and other malignancies revealed that BM can contain reactive germinal centers (GCs), complete with follicular DCs and surrounding T cells.20 This is supported by flow cytometric detection of GC B cells,21 and T follicular helper cells.22,23 Therefore, not only B-cell activation, but also subsequent affinity maturation, isotype switching, and plasmablast development, can occur in the BM24 (Figure 1A). Moreover, the BM contains significant numbers of memory B cells, which can rapidly differentiate into plasma cells upon local activation.25,26 Distinct subsets of BM memory B cells have recently been identified, the majority of which are noncirculating and resident to the BM, docking onto vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1+) stromal cells.27 These observations indicate that the BM serves not only as the generative organ for B-cell development but also serves as an SLT with great importance to systemic humoral immunity.

CD8+ T cells

Next to B cells and plasma cells, a large part of the mature lymphocyte pool in BM consists of T cells (supplemental Table 1). The percentage of CD8+ T cells is higher than the percentage of CD4+ T cells, which is different from the ratios in peripheral blood (PB) and SLTs (CD4:CD8 ratios in BM and PB are 0.7 and 2.0, respectively).28,29 In immunologically unchallenged mice, a large fraction (∼50% to 65%) of BM CD8+ T cells are naïve, whereas the remainder are central memory and effector memory cells.30,31 Importantly, this composition can change substantially upon immunologic challenge32,33 ; the frequency of effector memory CD8+ T cells in murine BM was shown to increase from ∼10% to ∼60% after recovery from lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection.30 In this model, virus-specific BM memory CD8+ T cells greatly outnumber those in the spleen, which is also a result of the large amount of BM distributed throughout the body.30

Adoptively transferred naïve CD8+ T cells migrate not only to SLTs but also to BM where they maintain a naïve phenotype34 and cluster around antigen-presenting cells (APCs)31,34 (Figure 1B). Ex vivo isolated central memory CD8+ T cells also rapidly home to BM as do effector memory CD8+ T cells, albeit to a lesser extent.32 Entry of CD8+ T cells into the BM is dependent on CXCR4, which is highly expressed on both naïve and memory CD8+ T cells.35,36 Contrary to plasmablasts,10 memory CD8+ T cells do not depend on their high expression of CXCR3 to enter the BM, despite local production of CXCL9 and CXCL10.35 BM memory CD8+ T cells are fully functional and mount recall responses when transferred into naïve mice.37 BM naïve CD8+ T cells can be activated by BM-resident DCs,34 which again demonstrates that BM acts as SLT. Although the presented antigens may be taken up from the blood,31,34 it has also been shown that neutrophils can transport viral antigens from the dermis to the BM, resulting in polyclonal CD8+ T-cell priming via APCs.38 Interestingly, these BM-primed CD8+ T cells exhibited differential effector functions and gene-expression profiles compared with their SLT-primed counterparts.38 This is consistent with a study in humans showing that BM CD8+ T cells have a different homing phenotype than those in other organs and that the BM selectively accumulates certain virus-specific memory CD8+ T-cell populations.39

Even though BM can serve as SLT, intravital imaging revealed that both naïve and memory CD8+ T cells are surprisingly immobile in the BM compared with SLT, and they interact with perivascular stromal cells that support their survival.35 This suggests that the BM is also important for maintaining CD8+ T cells in the absence of cognate antigen and that they temporarily reside in the BM to recharge on cytokines.40 Indeed, BM memory CD8+ T cells localize close to VCAM-1+ stromal cells, which produce high levels of IL-7, a cytokine critical for their survival.33,41 Moreover, these stromal niches also produce IL-15,35,42 which drives proliferation of memory CD8+ T cells43,44 (Figure 1B). Whether maintenance of BM memory CD8+ T cells depends on homeostatic proliferation or survival is heavily debated.45,46 Furthermore, although it is unclear how long these cells reside in the BM, most BM CD8+ T cells are in equilibrium with PB.47 However, a small pool of memory CD8+ T cells with specificities against a variety of peripheral and systemic antigens is truly resident and remains inside the BM.48 These data corroborate the notion that the BM is a key organ for maintenance of CD8+ T-cell–mediated immunologic memory. It should be noted that memory CD8+ T cells not only passively recharge in the BM but also produce soluble factors that enhance HSC self-renewal and maintenance5 (Figure 1B). This supportive function is altered when an infection induces CD8+ T-cell activation and production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), promoting HSC differentiation toward mature immune cells that eliminate the pathogen.49,50

CD4+ T cells

Naïve CD4+ T cells compose ∼60% of the total BM CD4+ T-cell pool,51 and like their CD8+ counterparts, they can be locally activated to generate robust immune responses.34 Not much is known about their localization, but they probably colocalize in clusters with local APCs like naïve CD8+ T cells.52 BM localization of memory CD4+ T cells has been studied in more detail; they are found in VCAM-1+IL-7+ stromal cell niches,53 similar to memory CD8+ T cells and B cells (Figure 1B). Importantly, BM CD4+ T cells do not homeostatically proliferate53 but are reactivated by cognate antigen, whereupon they proliferate and form clusters with B cells.54 These clusters are distinct from classical GCs, because the CD4+ T cells in them do not develop into T follicular helper cells, and the B cells do not acquire a GC phenotype.54

When activated, CD4+ T cells can produce many hematopoiesis-regulating cytokines, such as IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-17, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-γ, and TNF-α55-57 (Figure 1B). BM CD4+ T cells have a key role in maintaining normal hematopoiesis, because T-cell–deficient mice show defective terminal differentiation of myeloid cells, leading to an accumulation of immature myeloid cells in the BM and peripheral neutropenia.58 Normal granulopoiesis is restored upon reconstitution with CD4+, but not CD8+, T cells and is dependent on the activation state of the CD4+ T cells.58 Experiments with T-cell–specific deficiency of signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT-4) or STAT-6 showed that effector CD4+ T cells can also actively regulate hematopoietic progenitor cell homeostasis, possibly by secreting oncostatin M.4

The BM also contains a high fraction of Tregs compared with PB and SLTs, which make up ∼25% to 45% of total BM CD4+ T cells in humans and mice59-61 (supplemental Table 1). Tregs also depend on CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling for BM localization and are mobilized upon administration of granulocyte-CSF (G-CSF), which decreases BM CXCL12 levels.60,61 BM Tregs are important for preserving normal hematopoiesis,61,62 most likely because of their T-cell suppressive functions, and possibly because of their secretion of IL-10, which may stimulate HSC self-renewal.63

γδ T cells

γδ T cells constitute a small percentage of circulating T cells that participate in immune surveillance and innate immune responses because they recognize foreign and stress-induced self-antigens without previous antigen exposure.64 Unlike αβ T cells, γδ T cells are activated independently of major histocompatibility complex (MHC); they recognize lipids presented on CD1-family molecules and butyrophilin-like ligands.65 They mainly localize to epithelial and mucosal tissues, with T-cell receptor (TCR) differentiation and adaptations unique to their tissue environment.66 Subsets of γδ T cells can also follow an αβ-like adaptive pathway, including delayed activation, expansion, and establishment of memory.67 The 2 main subsets of γδ T cells, Vδ1+ and Vδ2+, are found in the BM (Figure 1C). Vγ9+Vδ2+ cells usually participate in innate-like immune responses, whereas Vγ9–Vδ1+ cells have been associated with adaptive-like responses.68,69 In murine BM, ∼2% of cells are γδ T cells.70 In human BM, ∼6% of T cells are γδ T cells, and the majority of these are Vγ9+Vδ2+, pointing to a high constitution of innate-like γδ T cells.71 Of these, 30% display a naïve, 30% a central memory, and 40% an effector memory phenotype72 (supplemental Table 1). Vγ9+Vδ2+ cells can act as innate effector cells and can kill tumor cells upon activation with aminobisphosphonates.73 Whether γδ T cells can also affect hematopoietic progenitor cells, as has been shown for αβ T cells, is unknown.

NKT cells

NKT cells are unconventional T cells that recognize glycolipids presented on CD1d. Type I NKT cells express an invariant TCR, whereas type II NKT cells express diverse TCRs. NKT cells lack CD8, but some cells do express CD4.74 Although NKT cells constitute only a minority of all BM T cells (supplemental Table 1), they can be activated by CD1d-expressing HSCs and modulate myelopoiesis by secreting GM-CSF and IFN-γ. NKT cell–deficient mice have significantly fewer leukocytes and platelets, lower BM cellularity, and fewer HSCs, suggesting that NKT cells positively regulate hematopoiesis75 (Figure 1C).

NK cells are cytotoxic lymphoid cells that recognize and lyse virus-infected and cancer cells that display distress signals and/or lack self-signals such as MHC-I and regulate immune responses through interactions with T cells, DCs, macrophages, and endothelial cells.76,77 NK cells are widely distributed throughout tissues in both humans and mice and constitute between 2% and 4% of the total lymphocytes in the BM77,78 (supplemental Table 1). BM NK cells are a major source of cytokines that regulate myelopoiesis, including IFN-γ and TNF-α.8 Upon gastrointestinal infection of mice with Toxoplasma gondii, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue–resident DCs produce systemic levels of IL-12, which stimulate BM-resident NK cells to produce IFN-γ and form clusters with developing monocytes. This induces an immune regulatory program in the monocytes before their egress into the blood and recruitment to the site of infection79 (Figure 1D).

ILCs

The family of noncytotoxic (helper) ILCs comprises 3 subsets: ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s.80 ILCs arise from HSCs via lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors, common lymphoid progenitors, and different committed ILC precursors (ILCPs), such as α-lymphoid precursors.81,82 Cxcl12 deletion studies showed that lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors, common lymphoid progenitors, and B-cell progenitors depend on and live in close proximity to CXCL12-secreting osteoblasts and perivascular stromal cells.83 In contrast, localization and niche requirements for more committed ILCPs and mature ILCs remain obscure. In adult humans, committed CD34+RORγt+ ILC3 progenitors are not found in the BM, but rather in tonsils and intestinal lamina propria, indicating that final maturation occurs at the definite site where ILC3s are required.84 This is consistent with recent findings that SLT-resident human ILCPs locally give rise to helper ILCs and cytotoxic NK cells.85 Importantly, these ILCPs were found in SLTs, but not in PB or BM. Yet, another study showed that certain ILCPs do circulate through PB and give rise to IFN-γ–producing ILC1s, IL-13–producing ILC2s, and IL-22–, but not IL-17–producing ILC3s within specific tissues.86 There are reports that ILC2s can be found in murine BM and ILC3s in human BM (supplemental Table 1), but systematic analyses of the presence, localization, and function of mature ILCs in the BM are still lacking (Figure 1D).

Pathophysiology of mature BM lymphocytes in autoimmune cytopenias

Non-neoplastic BM failure diseases are characterized by BM hypocellularity in ≥1 blood lineages and the resultant peripheral cytopenias. BM failure is found in several inherited syndromes, including Fanconi anemia, but it can also be acquired in diseases such as AA and ITP. In most patients with AA, immune-mediated injury to HSCs leads to BM hypocellularity in all 3 lineages, resulting in serious pancytopenia. HSCT is curative but is associated with substantial short- and long-term adverse effects; elderly patients are often ineligible because of comorbidities, and there is a worldwide shortage of HSC donors. Therefore, most patients with AA are treated with immunosuppressive therapies.7 In contrast to AA, ITP affects the megakaryocyte lineage only, leading to low platelet counts and the risk of bleeding. ITP is associated with polymorphisms in immunity-related genes, dysregulated T-cell responses to platelet surface antigens, and antiplatelet autoantibodies, resulting in increased platelet apoptosis and phagocytosis.87

Mechanistically, chronic exposure of HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors to inflammatory cytokines is associated with impaired self-renewal, HSC loss, and BM failure,50,88 as seen in AA and ITP89,90 (Figure 2). Because there is no convincing evidence for the recognition of exogenous antigens, a prevailing theory is that AA is mediated by autoreactive T cells.91 Activated T cells preferentially infiltrate residual hematopoietic areas in otherwise hypocellular BM biopsies from patients with AA, suggesting site-directed homing of autoreactive T cells in the pathogenesis of AA.92 Patients with AA exhibit significantly higher frequencies of activated CD8+ T cells in their BM than do healthy people. Those cells express high levels of CX3CR1,93 which mediates leukocyte chemotaxis and adhesion. Indeed, patients with AA have significantly higher fractalkine (CX3CL1) levels in BM plasma, which promotes chemotaxis and recruitment of CX3CR1+ T cells to BM and contributes to AA pathogenesis.93 BM T cells from patients with AA also express elevated levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ,89 which impedes HSC survival by disrupting suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2) and STAT pathways,94 impairing thrombopoietin-MPL signaling,88,95 and promoting apoptosis by upregulating Fas expression.96 CD8+ T cells also use perforin- and granzyme-mediated mechanisms to directly target HSCs97 (Figure 2B). Flow cytometry, spectratyping of complementarity-determining region 3 length skewing, and TCR Vβ sequencing revealed oligoclonal expansions of dysregulated effector-memory CD8+ T cells, suggesting that they respond to an HSC-expressed antigen.91,98

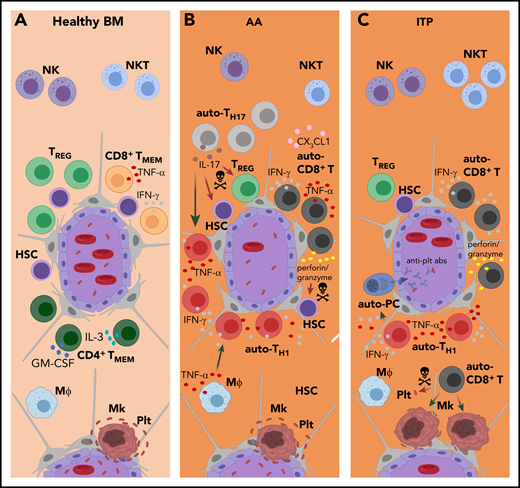

Pathophysiology of mature BM lymphocytes in autoimmune cytopenias. (A) In healthy BM, mature lymphocyte populations regulate HSC self-renewal, maintenance and hematopoietic output by producing soluble factors and likely by (as yet undefined) direct cell-cell interactions. (B-C) In AA and ITP, this delicate regulatory balance is distorted. For example, chronic exposure to high levels of inflammatory cytokines results in HSC loss, as seen in AA, and megakaryocyte (Mk) malfunction, as seen in ITP. (B) In AA, the patients’ BM is infiltrated by activated autoreactive (auto-)CD8+ T cells that express high levels of CX3CR1 and are recruited by CX3CL1 present in AA BM. BM auto-CD8+ T cells secrete high amounts of TNF-α and IFN-γ, and also use perforin- and granzyme-mediated mechanisms to directly target HSCs. Polyclonal BM auto-CD4+ T-cell numbers are increased in AA, and Th17-cell expansion is characteristic. Elevated levels of IL-17 impair hematopoiesis by depleting Tregs, directly inhibiting HSCs, and recruiting additional Th1 cells. IL-17 also promotes the secretion of TNF-α by macrophages (Mϕs), which in turn stimulates IFN-γ secretion by T cells. Patients with AA have reduced NK- and NKT-cell numbers in their BM. Whereas the significance of this finding for NKT cells is unclear, the reduction of BM NK cells in patients with AA may contribute to the excess of auto-CD8+ T cells as result of decreased T-cell killing by NK cells. (C) In patients with ITP, low platelet (plt) numbers are the predominant clinical feature. Presumably, BM auto-CD8+ T cells recognize megakaryocyte-derived antigens presented on platelets via MHC-I and can lyse platelets directly or induce platelet apoptosis. Moreover, suppression of megakaryocyte apoptosis by BM auto-CD8+ T cells directly inhibits platelet formation. BM auto-CD4+ T cells induce the production of anti-platelet autoantibodies (anti-plt abs) involved in disease pathogenesis. Patients with ITP have lower total numbers of CD4+ T cells in the BM than healthy controls. The disproportional loss of BM Th2 cells, as well as Tregs, results in a Th1 shift that contributes to autoantibody-mediated platelet destruction and T-cell cytotoxicity. The localizations and functions of BM NK and NKT cells in ITP are largely unknown.

Pathophysiology of mature BM lymphocytes in autoimmune cytopenias. (A) In healthy BM, mature lymphocyte populations regulate HSC self-renewal, maintenance and hematopoietic output by producing soluble factors and likely by (as yet undefined) direct cell-cell interactions. (B-C) In AA and ITP, this delicate regulatory balance is distorted. For example, chronic exposure to high levels of inflammatory cytokines results in HSC loss, as seen in AA, and megakaryocyte (Mk) malfunction, as seen in ITP. (B) In AA, the patients’ BM is infiltrated by activated autoreactive (auto-)CD8+ T cells that express high levels of CX3CR1 and are recruited by CX3CL1 present in AA BM. BM auto-CD8+ T cells secrete high amounts of TNF-α and IFN-γ, and also use perforin- and granzyme-mediated mechanisms to directly target HSCs. Polyclonal BM auto-CD4+ T-cell numbers are increased in AA, and Th17-cell expansion is characteristic. Elevated levels of IL-17 impair hematopoiesis by depleting Tregs, directly inhibiting HSCs, and recruiting additional Th1 cells. IL-17 also promotes the secretion of TNF-α by macrophages (Mϕs), which in turn stimulates IFN-γ secretion by T cells. Patients with AA have reduced NK- and NKT-cell numbers in their BM. Whereas the significance of this finding for NKT cells is unclear, the reduction of BM NK cells in patients with AA may contribute to the excess of auto-CD8+ T cells as result of decreased T-cell killing by NK cells. (C) In patients with ITP, low platelet (plt) numbers are the predominant clinical feature. Presumably, BM auto-CD8+ T cells recognize megakaryocyte-derived antigens presented on platelets via MHC-I and can lyse platelets directly or induce platelet apoptosis. Moreover, suppression of megakaryocyte apoptosis by BM auto-CD8+ T cells directly inhibits platelet formation. BM auto-CD4+ T cells induce the production of anti-platelet autoantibodies (anti-plt abs) involved in disease pathogenesis. Patients with ITP have lower total numbers of CD4+ T cells in the BM than healthy controls. The disproportional loss of BM Th2 cells, as well as Tregs, results in a Th1 shift that contributes to autoantibody-mediated platelet destruction and T-cell cytotoxicity. The localizations and functions of BM NK and NKT cells in ITP are largely unknown.

Activated CD4+ T cells also have the potential to disrupt hematopoiesis, and polyclonal expansion of dysregulated CD4+ T cells is implied in AA pathogenesis.99 T helper 1 (Th1)-, Th2-, and Th17-cell expansions are characteristic of AA.100 Elevated IL-17 levels may impair hematopoiesis by depleting Tregs,100 directly inhibiting HSCs,101 recruiting Th1 cells,100 and/or by inducing macrophages to secrete TNF-α.102 TNF-α in turn stimulates IFN-γ secretion from T cells,103 accelerating HSC impairment. Oligoclonal or monoclonal expansion of Th1 cells,104 increased T-bet (a T-box transcription factor) expression, and abnormally high production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 are also typical for AA, indicating a Th1 response–based pathogenesis105,106 (Figure 2B).

Autoreactive CD8+ T cells are also implicated in the pathophysiology of ITP. In patients with ITP, BM T cells express more VLA-4 and CX3CR1 and make up 81% of BM lymphocytes (vs 55% in healthy controls), suggesting that increased BM T-cell recruitment is part of ITP pathogenesis.107 Most of those CD8+ T cells are cytotoxic, expressing high levels of TNF, FASLG, PRF1, and GZMB messenger RNAs, and they can lyse platelets directly or induce platelet apoptosis108,109 (Figure 2C). The antigens recognized by CD8+ T cells in ITP have not yet been identified, but they might recognize megakaryocyte- or pathogen-derived antigens presented on platelets via MHC-I. ITP BM CD8+ T cells can also inhibit platelet formation by suppressing megakaryocyte apoptosis.110

CD4+ T cells also display a Th1 shift in ITP, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa-autoreactive CD4+ T cells induce the production of antiplatelet autoantibodies involved in disease pathogenesis111 (Figure 2C). The Th1 shift in ITP is a result of a decrease in Th2 cells,112 suggesting a different mechanism than the T-bet induction observed in AA. In addition, and contrary to AA, the fraction of CD4+ T cells in ITP BM is lower than that in healthy controls (40% vs 61%, respectively).110

Treg malfunction is associated with both AA and ITP. Circulating CD4+CD25+ T cells in patients with AA have significantly lower levels of FoxP3 than those in healthy controls, and significantly decreased or absent levels of NFAT1, the master regulator for FoxP3 expression.113 Patients with AA also display an inverse correlation of Th17 and Treg numbers,100 the differentiation of which is reinforced by specific cytokine milieus.114 This indicates that the immune system is polarized toward a Th1/Th17 response, with Treg deficiency contributing to the development of AA.100 Treg deficiency is also implicated in the pathogenesis of ITP; patients with ITP have fewer BM Tregs than do healthy controls (5% vs 11% of CD4+ cells, respectively). Lower levels of Tregs and Treg-secreted factors such as transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) contribute to destruction of platelets by antibodies and T cell–mediated cytotoxicity in ITP107 (Figure 2C).

Little is known about the role of γδ T cells in AA. γδ T cells in the BM of patients with AA are significantly decreased compared with those in healthy controls,115 but they are increased in patients with acquired pure red cell aplasia.116 In pediatric ITP, significant increases in polyclonally expanded Vγ9+Vδ2+ T cells (to up to 48% of all T cells) were observed in PB, and reductions in these cells directly correlated with recovery, implicating a role for γδ T cells in ITP pathogenesis. γδ T cells may induce platelet destruction by secreting cytokines such as IL-2, GM-CSF, and IFN-γ by enhancing antibody production by autoreactive B cells, by direct cytolysis, or via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.117,118 Moreover, ITP can present as the first symptom of hepatosplenic γδ T-cell lymphoma as a result of BM involvement by malignant γδ T cells.119 This is seen in approximately two-thirds of patients, typically with a sinusoidal infiltration pattern that can compose up to 30% of all BM cells.120

Patients with AA exhibit reduced BM NKT cells, which display a more diverse, polyclonal TCR repertoire, but the significance thereof remains unclear.121 Stimulating NKT cells from AA mice with α-galactosylceramide inhibits IFN-γ production and enhances IL-4 secretion, which restores hematopoietic colony formation in vitro.122 The role of NKT cells in ITP is less clear. One study reported increased NKT cell numbers in patients with severe ITP, suggesting that NKT cells may drive ITP pathogenesis.123 Other studies reported that NKT cell function was reduced in untreated patients with ITP124 and that NKT cell activation suppressed platelet-induced T-cell proliferation in vitro,125 suggesting a protective role for NKT cells in ITP. Similar to NKT cells, NK cells in PB and BM of patients with AA are significantly reduced, and their cytotoxic functions are impaired; these parameters are restored upon immunosuppressive therapy.126,127 Because NK cells regulate CD8+ T cells via direct killing,128 impaired NK cell cytotoxicity and the resulting excess of autoreactive CD8+ T cells likely contribute to AA pathogenesis129 (Figure 2B). In contrast, in ITP, NK cells can lyse platelets directly and contribute to disease pathogenesis.130 However, the role of BM NK cells in this process is largely unknown because most studies on the role of NK cells in ITP focused on PB or spleen, and results are contradictory. In 1 study, PB NK cell frequencies were approximately twice as high in patients with ITP compared with those in healthy controls.131 Another study reported largely unaltered NK cell frequencies in PB and spleen; however, their cytotoxic functions were impaired132 as in AA.126

ILCs are altered in their distribution and function in the spleens of patients with ITP, with increased numbers of IFN-γ– and IL-2–producing ILCs, although no data on BM were reported.133 On the basis of their comparable cytokine profile, it is tempting to speculate that ILCs could have a similar impact on HSCs and progenitors as TCR-expressing lymphocytes.

To summarize, the efficacy of immunosuppressive therapies in AA and ITP provides a strong pathophysiological link to immune-mediated mechanisms, likely executed by BM-resident mature lymphocytes. Antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporin, in combination with the MPL agonist eltrombopag, are effective in most patients with AA, which is in line with the mainly T-cell–driven autoimmune process in AA.134 Nowadays, patients with ITP are most commonly treated with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, or rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody; splenectomy is reserved for refractory cases.135,136 The efficacy of rituximab confirms that B cells and autoantibodies are involved in the pathophysiology of ITP; this is corroborated by a report showing that the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, which targets long-lived plasma cells, also alleviated ITP.137 Thus, targeting BM plasma cells may be an interesting therapeutic strategy for autoimmune cytopenias as well.

Pathophysiology of mature BM lymphocytes in HSCT

HSCT is a cornerstone therapy for numerous hematologic diseases. Mature lymphocyte populations support HSC engraftment and execute graft-versus-tumor effects, but they are also key players in GVHD, a major cause of morbidity and mortality after HSCT. GVHD is induced by donor-derived T cells as well as persisting tissue-resident recipient T cells that are activated by donor APCs.138 In contrast, Tregs are known to alleviate GVHD and promote immune reconstitution after HSCT.139,140 Although many functions of different T-cell subsets in HSCT have been elucidated (Figure 3A), much still needs to be learned about the role of other lymphocyte populations such as ILCs and the localization and contribution of their specific niches.

Pathophysiology of mature BM lymphocytes in HSCT. (A) In HSCT, donor BM CD8+ T cells support HSC engraftment by facilitating HSC entry into the BM, inhibiting their exit, and suppressing host-derived alloreactive (allo-) BM CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. NKT cells are resistant to irradiation, a common conditioning regimen in HSCT, leading to an altered NKT-cell/T-cell balance in the BM and IL-4 production by host BM NKT cells. This results in Th2-polarization of donor BM T cells and induction of IL-10–producing donor BM Tregs, which improve HSC engraftment. Moreover, donor BM Tregs preferentially accumulate around donor HSCs and provide immune protection. In addition, they promote B-cell reconstitution by facilitating IL-7 production from BM perivascular stromal cells. High numbers of donor-derived CD27+ γδ T cells post-HSCT correlate with longer disease-free survival, but the exact localization of those cells, and whether they home to the BM, is not known. (B) GVHD is mediated by activated donor T cells and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after HSCT. High levels of naïve and central-memory allo-CD8+ T cells correlate with increased GVHD risk. Donor BM allo-CD8+ T cells can induce host plasma cell destruction. In addition, activated donor CD8+ T cells likely negatively affect HSCs in GVHD through secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IFN-γ. Moreover, donor-derived alloantibodies, presumably secreted by plasma cells in BM, can promote cutaneous chronic GVHD. Host BM NKT cells can ameliorate GVHD by inhibiting the proliferation and preventing the activation of allo-CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Finally, donor-derived CD8+ γδ T cells are associated with higher incidences of GVHD, but the role of BM in this process is unknown.

Pathophysiology of mature BM lymphocytes in HSCT. (A) In HSCT, donor BM CD8+ T cells support HSC engraftment by facilitating HSC entry into the BM, inhibiting their exit, and suppressing host-derived alloreactive (allo-) BM CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. NKT cells are resistant to irradiation, a common conditioning regimen in HSCT, leading to an altered NKT-cell/T-cell balance in the BM and IL-4 production by host BM NKT cells. This results in Th2-polarization of donor BM T cells and induction of IL-10–producing donor BM Tregs, which improve HSC engraftment. Moreover, donor BM Tregs preferentially accumulate around donor HSCs and provide immune protection. In addition, they promote B-cell reconstitution by facilitating IL-7 production from BM perivascular stromal cells. High numbers of donor-derived CD27+ γδ T cells post-HSCT correlate with longer disease-free survival, but the exact localization of those cells, and whether they home to the BM, is not known. (B) GVHD is mediated by activated donor T cells and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after HSCT. High levels of naïve and central-memory allo-CD8+ T cells correlate with increased GVHD risk. Donor BM allo-CD8+ T cells can induce host plasma cell destruction. In addition, activated donor CD8+ T cells likely negatively affect HSCs in GVHD through secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IFN-γ. Moreover, donor-derived alloantibodies, presumably secreted by plasma cells in BM, can promote cutaneous chronic GVHD. Host BM NKT cells can ameliorate GVHD by inhibiting the proliferation and preventing the activation of allo-CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Finally, donor-derived CD8+ γδ T cells are associated with higher incidences of GVHD, but the role of BM in this process is unknown.

Donor CD8+ T cells support HSC engraftment by inactivating the host response against donor MHC-I alloantigens141 and suppressing host-derived immune cells.142 CD8+ T cells also facilitate BM entry and inhibit BM exit of donor HSCs,143,144 potentially by modulating phosphotyrosine-mediated signaling in response to CXCL12.144 However, although higher frequencies of donor CD8+ T cells support HSC engraftment, they are also associated with a higher likelihood of GVHD.145 Naïve and, to a lesser extent, central-memory (but not effector-memory) CD8+ T cells mediated GVHD in mice in both MHC-mismatched and MHC-matched recipients.146 Therefore, naïve T-cell depletion has been investigated as a means of reducing GVHD in HSCT.147,148 In addition, based on the pathophysiological changes that take place in AA, ITP, and viral infections, it is likely that activated donor CD8+ T cells modulate HSCs and hematopoiesis in GVHD through production of proinflammatory cytokines (Figure 3B).

The role of CD4+ T cells in HSCT has mostly been addressed in view of Tregs and GVHD. In patients with severe GVHD, there is an imbalance between Tregs and effector CD4+ T cells, mainly because of an overrepresentation of effector-memory CD4+ T cells.149,150 Although the positive functions of effector CD4+ T cells on HSC engraftment are somewhat clear, more is known about the role of Tregs. After HSCT in mice, donor-derived Tregs preferentially localize to the endosteal surface, accumulating around donor HSCs and providing immune protection by preventing allorejection. Therefore, Treg depletion resulted in a loss of 75% to 90% of donor HSCs.59 A distinct subset of CD150hi Tregs localizes in perivascular HSC niches, where they provide immune privilege and maintain HSCs quiescence.61 Cotransplantation of niche-associated CD150hi Tregs improved HSC engraftment to a greater extent than did transplantation of CD150low Tregs.61 Recently, CD4+CD150hiFoxP3– T cells were shown to play a similar role in regulating HSCs. It was postulated that CD150hi Tregs and CD4+CD150hiFoxP3– T cells generate extracellular adenosine in a coordinated fashion via CD39/CD73, maintaining HSC quiescence and improving engraftment by protecting HSCs from oxidative stress.151 Tregs are also important in B-cell reconstitution after HSCT. Treg depletion diminished the production of IL-7, an important B-cell survival factor, by ICAM+ perivascular stromal cells, possibly as a result of the inflammatory cytokine milieu induced by autoreactive T cells.62

B cells, plasma cells, and antibodies play an important and complex role in GVHD.152 Although the precise role of BM herein is less clear, donor B-cell–derived antibodies can promote cutaneous chronic GVHD.153 Moreover, gradual destruction of host plasma cells by GVHD is an important reason why host antidonor isohemagglutinins gradually disappear after ABO-mismatched HSCT.154,155 Therapeutic efficacy of donor plasma cell depletion for treatment of chronic GVHD is being tested in a phase 2 clinical trial using pomalidomide, an immunomodulatory drug for multiple myeloma (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01688466). This is in line with the proven efficacy of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, which also targets long-lived plasma cells and thereby alleviates GVHD.156,157

Recent studies suggest a favorable role for γδ T cells in HSCT.158 After HSCT, reconstitution of γδ T cells is largely the result of clonal expansion of donor-derived cells.159,160 High numbers of CD27+ γδ T cells post-HSCT correlated with longer disease-free survival.71 In addition, CD8+ γδ T cells were associated with a higher incidence of GVHD, whereas the frequency of CD8– γδ T cells tended to correlate with lower GVHD rates, suggesting a possible immunoregulatory role.71 Studies in leukemia patients who had undergone HSCT with αβ T cell-depleted grafts indicated that γδ T cells facilitate the graft-versus-leukemia effect without causing GVHD.161 This phenomenon may be explained by γδ T cells not being HLA-restricted, which reduces the chance of GVHD triggered by HLA-mismatch.158

The importance of NK cells and NKT cells has also been documented in HSCT. NK cells were shown to facilitate the engraftment of HSCs in HSCT models using reduced myeloablative conditioning regimens and IL-15162 as well as in cord blood HSCT.163 The resistance of NKT cells to irradiation leads to an altered NKT cell/T cell balance after conditioning and IL-4 production by host NKT cells, resulting in Th2 polarization of donor T cells and induction of IL-10–producing donor Tregs, which ameliorates GVHD74,164 (Figure 3B). Tracking studies of ILCs in patients with acute myeloid leukemia who are receiving chemotherapy and HSCT revealed that abundance of ILC before and reconstitution of ILC after induction chemotherapy was associated with protection from GVHD. This was mediated by donor ILC3s expressing CD69 and tissue-homing markers for the gut and skin.165 A possible mechanism for GVHD protection is ILC3-derived IL-22, a cytokine associated with epithelial homeostasis. Indeed, ILC3s proliferate and upregulate IL-22 production when cocultured with BM-derived mesenchymal stem cells,166 suggesting that ILC3s may harbor in an mesenchymal stem cell–containing BM niche.

Conclusions

BM is a highly dynamic organ with complex, intertwined functions necessary for hematopoiesis and immunity, many of which can be regulated by mature lymphocytes residing within it. Thoroughly characterizing different BM lymphocyte populations, their diverse states and microenvironments, and the cells they interact with will improve our understanding of homeostatic and disordered hematopoiesis and possibly lead to novel therapies for diseases such as AA and ITP. Future studies of BM lymphocyte populations should therefore combine functional assays with high-dimensional analysis technologies, including single-cell RNA sequencing, mass cytometry, multiplexed tissue imaging, and 3D microscopy.3,167-169 This will enable a deeper understanding of the diversity, localization, and (patho)physiology of these different cell types and how they interact with hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marieke Goedhart (Sanquin Research, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for giving key input to this review and Katherine MacNamara (Albany Medical College, Albany, NY) for critically reading the manuscript and providing constructive feedback. Parts of the figures were created with BioRender.com.

C.M.S. was supported by an Advanced Postdoc Mobility Fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (P300PB_171189 and P400PM_183915) and an International Award for Research in Leukemia from the Lady Tata Memorial Trust (London, United Kingdom).

Authorship

Contribution: C.M.S. conceived of the review; C.C. created the figures; and all authors contributed equally to the study by writing, editing, and approving the final version of the review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Martijn A. Nolte, Sanquin Research, Plesmanlaan 125, Room Y308, 1066CX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: m.nolte@sanquin.nl; and Christian M. Schürch, Department of Pathology, Liebermeisterstrasse 8, Room 125, 72076 Tübingen, Germany; e-mail: christian.schuerch@med.uni-tuebingen.de.