Abstract

Introduction: Time and resource barriers limit widespread implementation of frailty assessment in oncology practice, and the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the number of in-person visits. To overcome these barriers, virtual geriatric assessments (GAs) have been developed, but lack important objective performance measures such as gait speed and cognitive tests-measures that are important predictors for poor outcomes in older patients with blood cancers (Liu et al., Blood, 2019; Hshieh et al., JAMA Oncol., 2018). We adapted an in-person frailty assessment to a virtual format that maintained both patient-reported and objective measures.

Methods: Our cohort assessed in-person (February 2015 to March 2020; resumed June 2021 to July 2021) included all transplant-ineligible patients aged 75 years and older who presented to DFCI for initial consultation for their hematologic malignancy. On the same day as their initial consult, a research assistant administered to consented patients a screening geriatric assessment that assessed for 42 aging-related health deficits using patient-reported and objective performance measures spanning the domains of function, cognition, comorbidity, and mobility. From this assessment, frailty was measured using both the phenotypic (Fried et al., J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2001) and deficit-accumulation approaches (Rockwood et al., J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2007). The frailty phenotype uses five criteria to define a syndrome (slow gait speed, weakness [grip strength], self-reported exhaustion, low physical activity, and weight loss). The deficit-accumulation method calculates the proportion of deficits present in an individual out of the total number of possible deficits measured.

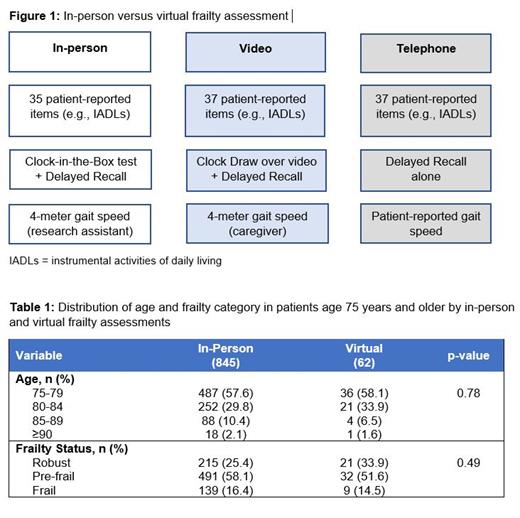

To virtually adapt our assessment (Figure 1), patient-reported items were readily converted to questions administered over video- or teleconference. Of the objective measures, grip strength was replaced with self-reported grip strength. The Clock-in-the-Box test was changed to a simple clock draw that the patient completes and displays to the video camera for scoring. 4-meter gait speed is collected by teaching a caregiver to administer with a stopwatch and a 4-meter strip of ribbon. If video is unavailable, self-reported gait speed is measured instead. We expanded eligibility of virtual assessments to patients aged 70 and older.

Geriatricians (C.D., T.H., and J.D.) and oncologists (G.A. and J.D.) reviewed the virtual GA for content validity. We measured the proportion of patients who consented and completed the virtual assessment. We assessed for differences in the distributions of age and frailty between virtual and in-person frailty assessments in patients 75 and older using Fisher exact (age) and Chi-square (frailty) tests.

Results: Since starting our virtual frailty assessments in November 2020 through July 2021, 118 patients were enrolled and 89 (75%) completed assessments. Median age was 77.6 years (SD = 4.21), 55 (62%) were male, 38 (43%) had lymphoma, 32 (36%) had leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative disorders, and 19 (21%) had multiple myeloma. Of the 89 who completed virtual assessments, 67 (75%) completed the assessment over video with the remaining 22 (25%) over telephone. For the objective measures, 68 (76%) participants were able to complete the clock draw and 47 (53%) were able to complete the gait speed tests. The distribution of age (p = 0.78) and frailty categories (p = 0.49) in our virtual assessments was similar to that of our in-person assessments (Table 1).

Conclusion: We developed and successfully delivered a virtual frailty assessment for older adults with blood cancers and found no evidence that frail patients or patients of the highest age categories were unable to complete them. These data suggest that virtual frailty assessment will allow decentralization of assessments even beyond the pandemic, potentially reaching more older adults with blood cancers. The ability to scale to more patients and measure frailty where it matters most-in their own homes-could help overcome barriers to frailty assessments in busy oncology clinics. Virtual frailty assessments also allow for serial measurement while on treatment to better understand and track the trajectory of frailty in this population.

Kim: Alosa Health: Other: Personal Fee; NIH: Other: Grants; Alosa Health: Other: Personal Fee.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal