Abstract

Introduction: The incidence of multiple myeloma (MM) varies by ethnicity with Black patients approximately twice as likely to develop MM compared to White or Asian (Black: White males 2.9:1, females 2.2:1). The National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) in 2015 reported the incidence of MM by ethnicity in England over 10 years to be 85.5% White; 5.4% Black; 3.6% Asian and 1.9% Other. Ethnic minorities have been reported to be under-represented in clinical trials partly because of socio-economic factors; however, it is unknown if these disparities exist in state funded health care systems where access to healthcare is free and should be equitable.

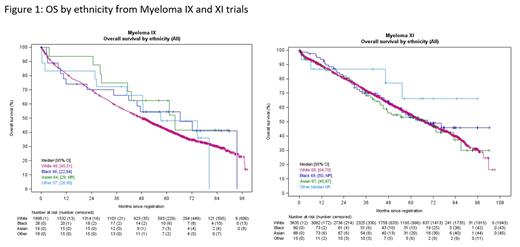

Methods: Ethnicity, baseline demographics, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were collected from patients enrolled into 1 st line UK academic transplant eligible (TE) and transplant non-eligible (TNE) - Myeloma IX, XI and XIV trials, and at 1 st relapse - Myeloma X and XII clinical trials. These trials enrolled from 2003 to 2021. The Myeloma XII and XIV (FiTNEss) trials are currently enrolling, all other trials have closed. Ethnicity was coded by White, Black, Asian and Other in line with Office for National Statistics (ONS) categories. Patients were enrolled across 120 centres covering a wide geographical distribution in the UK. These studies were designed to have permissive eligibility criteria to enrol as close to real world patients as possible. Baseline characteristics were summarised descriptively and comparisons made using the chi-squared test. Comparisons with population-level data used one-sample chi-squared tests. Survivor functions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using the logrank test. Cox proportional hazards models with suitable interaction terms were used to test for heterogeneity. All tests were called significant at the 5% level.

Results: 7,291 patients were enrolled across 5 randomised controlled trials over 18 years. Overall, the ethnic distribution was White 93.8%, Black 2.2%, Asian 1.8%, Other 0.6% and unknown 1.6%. The skew to enrolment of White patients was more apparent in the TNE studies (Myeloma IX non-intensive: White 97.4%, Black 1.3%, Asian 0.4%; Myeloma XI non-intensive: White 94.5%, Black 1.8%, Asian 1.6%, Myeloma XIV: White 94.2%, Black 0%, Asian 3.2%). This was different to the incidence of myeloma cases across the UK with the difference most apparent in TNE studies (TE trials (observed vs NCRAS, P < 0.0001); TNE trials (observed vs NCRAS, P < 0.0001); 1 st relapse trials (observed vs NCRAS, P = 0.035)). Enrolment distribution by ethnicity was consistent over the 18 years, with no change in diversity over time despite there being an increase in UK non-white populations.

In the Myeloma IX trial, there was no significant difference in age at enrolment; however, the performance status in Black patients was worse than non-Black (P = 0.045), there was fewer cytogenetic high risk Black patients (P = 0.007) and less ISS 1 Black patients vs non-Black (P = 0.0416). There were no demographic differences by ethnicity in the Myeloma XI trial.

The outcomes of patients by PFS or OS by ethnic group was similar within each trial (figure 1). An overall improvement in OS for was demonstrated over time from Myeloma IX to the Myeloma XI trial with the incorporation of novel agents (median OS MRC-Myeloma IX: 48 months vs. median OS NCRI Myeloma-XI: 70 months, P < 0.0001). There was no evidence of heterogeneity of effect with respect to ethnicity (P = 0.456) suggesting all ethnic sub-groups benefited from this improvement in OS.

Conclusions: Enrolment of ethnic minorities into academic clinical trials in the UK was below that expected despite enrolling from >100 geographically spread sites and intended equitable access to healthcare. All ethnic groups derived an OS benefit from novel agents within trials that were not otherwise routinely available; however, a substantial proportion of ethnic minorities were not enrolled particularly TNE patients, thereby limiting their survival gains. Understanding causes of inequality and addressing these is a priority for the UK-MRA to ensure that all groups can potentially benefit, and trial results are representative of the UK population.

Popat: Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, and Celgene: Consultancy; AbbVie, BMS, Janssen, Oncopeptides, and Amgen: Honoraria; Takeda: Honoraria, Other: TRAVEL, ACCOMMODATIONS, EXPENSES; GlaxoSmithKline: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding; Janssen and BMS: Other: travel expenses. Craig: Celgene: Research Funding; Merck Sharpe & Dohme: Research Funding; Amgen: Research Funding; Takeda: Research Funding. Davies: Takeda: Consultancy, Honoraria; Janssen: Consultancy, Honoraria; Roche: Consultancy, Honoraria; Amgen: Consultancy, Honoraria; BMS: Consultancy, Honoraria; Abbvie: Consultancy, Honoraria. Cairns: Amgen: Research Funding; Merck Sharpe and Dohme: Research Funding; Takeda: Research Funding; Celgene / BMS: Other: travel support, Research Funding. Olivier: Merck Sharpe and Dohme: Research Funding; Takeda: Research Funding; Amgen: Research Funding; Celgene / BMS: Research Funding. Morgan: BMS: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Jansen: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Karyopharm: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Oncopeptides: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; GSK: Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees. Cook: BMS/Celgene: Consultancy, Research Funding; Janssen: Consultancy, Research Funding; Takeda: Consultancy, Research Funding; Sanofi: Consultancy; Karyopharm: Consultancy; Amgen: Consultancy.

Revlimid and carfilzomib combinations are used off label

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal