Abstract

Introduction Race-ethnic disparities in acute leukemia research participation limit generalizability and equitable access to novel therapies. We recently found substantial clinical trial enrollment disparities between National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (CCC) hospitals and the catchment areas for which they assume cancer control and treatment responsibility (Hantel JCO 2022). A first step in remediating such participatory disparities is understanding how underserved populations access care at these hospitals.

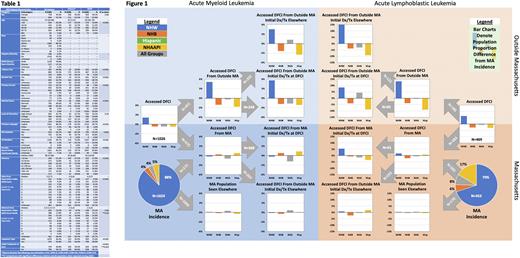

Methods We analyzed hospital access and initial treatment data for a large CCC hospital, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), relative to its catchment area, Massachusetts (MA), for all patients diagnosed with acute myeloid or lymphoblastic leukemia between 2014-2018. DFCI data were from an institutional cancer registry (OncDRS) that includes rich demographic, treatment, and outcome data; state data were from the MA Cancer Registry. We assessed access proportions (2+ visits for leukemia care) between mutually exclusive race-ethnic groups, using X2 testing, as patients moved from the incident populations within and outside the catchment area to the hospital, and based on their place of initial treatment. Non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) were the comparator with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported. For some comparisons, race-ethnicity of was dichotomized as NHW and Diverse (Hispanic White and Hispanic- or non-Hispanic-Black, -Asian/Pacific Islander, -Native American, -another race, and -two or more races). We performed logistic regression modeling of demographics, social determinants of health, and disease characteristics (Table 1) to assess their association with DFCI as the site of initial treatment using complete cases.

Results From 2014-18 there were 2077 incident cases of acute leukemia in MA, of which 858 (41.3%) were seen at DFCI. During the same period, 1622 patients with acute leukemia accessed care at DFCI, of which 764 (47.1%) were from outside MA; DFCI patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Hospital access and location of initial treatment proportions by leukemia subtype, race-ethnicity, and place of residence are shown in Figure 1: bar charts show differences for race-ethnic groups relative to MA incidence proportions, which are displayed in the pie charts. Relative to MA incidence, there was no significant difference in DFCI access by dichotomized race-ethnicity (Diverse vs NWH OR 0.87; 95% CI 0.73,1.05). Among MA residents, NHWs were not more likely to access DFCI than those from Diverse race-ethnicities (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.65,1.04). NHW were more likely to have received initial treatment at DFCI (OR 1.59; 95% CI 1.12,2.28). Conversely, patients accessing DFCI from outside MA were more likely to be NHW (OR 1.94; 95% CI 1.42,2.65) but were equally likely to have received initial treatment at DFCI (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.62,1.74). In a multivariable model assessing site of initial treatment receipt for those having accessed DFCI, including only variables from Table 1 that univariably predicted initial treatment site (with predicted defined as p<0.05: age, race-ethnicity, leukemia subtype, alcohol and tobacco use, marital status, primary language, and primary insurer), NHW race-ethnicity was not independently associated with initial treatment receipt (OR 0.69; 95%CI 0.47,1.02) but older age (OR 1.02; 95%CI 1.01,1.03), AML subtype (OR 2.62; 95%CI 1.91,3.95), and primary Medicare insurance (OR 1.70 vs private; 95%CI 1.24,2.31) were.

Conclusions For this large and high-enrolling CCC hospital, overall access to leukemia care did not significantly differ by race-ethnicity. This welcome finding suggests that participatory equity for acute leukemia clinical research is achievable at such sites. Known participatory disparities, however, are significant and prevalent. The disparities in access from outside the catchment area and initial treatment within it define targetable issues that impact the ability of under-enrolled populations to participate in clinical research equitably. Next steps include correlating access and enrollment data and developing real-time participatory diversity monitoring tools.

Disclosures

Luskin:Abbvie: Research Funding; Pfizer: Honoraria; Novartis: Research Funding. Brunner:Takeda: Consultancy, Research Funding; Taiho: Consultancy; Novartis: Consultancy, Research Funding; Keros Therapeutics: Consultancy; Janssen: Research Funding; GSK: Research Funding; Celgene/BMS: Consultancy, Research Funding; AstraZeneca: Research Funding; Agios: Honoraria; Acceleron: Honoraria; Aprea: Research Funding. Stone:Syntrix: Consultancy; GSK: Consultancy; BerGenBio: Consultancy; Boston Pharmaceuticals: Consultancy; Astellas: Consultancy; BMS: Consultancy; Elevate Bio: Consultancy; Epizyme: Consultancy; Novartis: Consultancy; Kura Oncology: Consultancy; Jazz: Consultancy; Janssen: Consultancy; Innate: Consultancy; Gemoab: Consultancy; Foghorn Therapeutics: Consultancy; Syndax: Consultancy; OncoNova: Consultancy; Actinium: Consultancy; Abbvie: Consultancy, Research Funding; Apteva: Consultancy; Aprea: Consultancy; Arog: Consultancy, Research Funding; Syros: Consultancy; Takeda: Consultancy. DeAngelo:Abbvie: Research Funding; Blueprint Medicines Corporation: Consultancy; Incyte: Consultancy; Forty-Seven: Consultancy; Autolus: Consultancy; Agios: Consultancy; Amgen: Consultancy; Glycomimetics: Research Funding; Shire: Consultancy; Takeda: Consultancy; Novartis: Consultancy, Research Funding; Pfizer: Consultancy; Jazz Pharmaceuticals: Consultancy. Abel:Novartis: Consultancy.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal