In this issue of Blood, Ruan et al1 present the results of a phase 2 study that explores the approach of epigenetic priming with the oral hypomethylating agent (HMA) azacitidine in combination with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy for the upfront treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

PTCLs are a group of heterogeneous lymphomas. Unfortunately, PTCLs generally have disappointing response rates and short durations of response to cytotoxic chemotherapy.2 The current upfront approach in PTCL of using anthracycline-containing regimens, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is largely based on extrapolation from studies in aggressive lymphomas that included few participants with PTCL. However, outcomes in PTCL if treated with the same regimes are significantly worse compared with matched patients with aggressive B-cell lymphomas,3 and cytotoxic chemotherapy is rarely curative.2 Attempts at intensification of cytotoxic regimens have largely been unsuccessful in improving survival, with the possible exception of adding etoposide to initial therapy and consolidation in first remission with high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell rescue, although the benefits of these strategies may be limited to select PTCL subtypes.4 This highlights the need for integrating novel agents into treatment strategies. Abnormalities in epigenetic modifiers have been identified in several PTCL subtypes, particularly those derived from T follicular helper (TFH) cells, and therapies targeting the epigenome can result in durable responses.5

Over the past decade, our understanding of PTCL pathobiology has grown significantly. New insights include the occurrence of recurrent mutations in epigenetic regulators, specifically in PTCLs with a TFH phenotype.6 Partly based on genetic profiling, the entities previously referred to as angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, follicular T-cell lymphoma, and PTCL with TFH phenotype are now united into the new family of nodal TFH cell lymphomas (nTFHLs) in the most recent World Health Organization classification.7 nTFHLs are characterized by a common mutational landscape that results in dysregulation of the epigenome and T-cell receptor signaling.7 The resulting vulnerability to epigenetic therapies such as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) and HMAs has been demonstrated in the relapsed and refractory setting.5,8

Ruan et al investigated the role of epigenetic priming with the oral DNA methyltransferase inhibitor azacitidine (Aza) administered prior to each cycle of CHOP chemotherapy (Aza-CHOP). This single-arm phase 2 study included 21 adult participants, of which 81% (n = 17) had nTFHL. Of the evaluable 20 participants, 75% achieved a response to Aza-CHOP, all complete responses (CRs). The overall response rate (ORR) and CR rate for the nTFHL subset was higher at 88% than for the entire group. This translated into an estimated 2-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of 65.8% and 68.4% for all-comers, and a 2-year PFS and OS of 69.2% and 76.1%, respectively, for nTFHL. Notably, some participants experienced clinical responses to oral Aza alone; however, no responses were seen in the non-nTFHL participants. The regimen was largely well tolerated, with the most common side effects hematological and no treatment-related deaths. CHOP chemotherapy doses did not require modification for any participant.

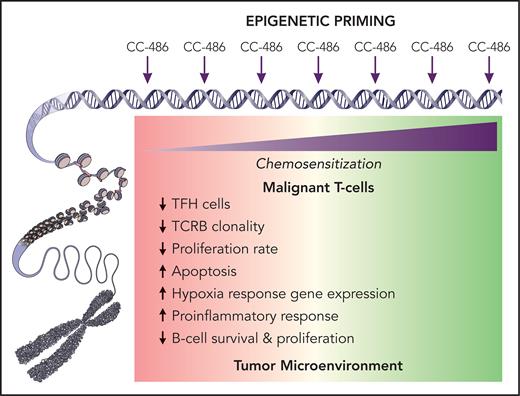

Extensive correlative studies included mutational profiling that showed the expected mutations in TET2 (76.5%), RHOA (41.1%), DNMT3A (23.5%), and IDH2 (23.5%). TET2 mutations were associated with favorable outcomes (improved CR, PFS, and OS), whereas DNMT3A mutations were associated with a worse PFS. Clonal evolution of a DNMT3A R326C clone at relapse was found in 1 participant and may represent an acquired resistance mechanism. Azacitidine priming resulted in differential gene expression affecting several pathways (see figure) that suggests a chemo-sensitizing reprograming effect on the TME and potentially the neoplastic T cells, although no significant changes in genome-wide DNA methylation in paired tumor samples were seen.

Azacitidine at low doses serves as an epigenetic modifier by regulating DNA methylation, whereas at higher doses it can be directly cytotoxic. Ruan et al administered oral azacitidine (CC-486) prior to each cycle of cytotoxic CHOP therapy in PTCL. When examining pharmacodynamic effects on 5 paired tumor samples, they observed differential gene expression before and after CC-486 administration in gene sets related to inflammatory response and hypoxia, suggesting a favorable change in the composition of the tumor microenvironment (TME) facilitated by CC-486. Furthermore, gene-based cell subtype deconvolution showed a trend towards lower TFH lymphoma cells and proliferation suggesting a possible directly antineoplastic effect on malignant T cells, particularly TFH cells. Although the exact mechanisms of the potentially chemosensitizing changes remain to be further elucidated, epigenetic priming may lead to a favorably disposed and likely more “inflammatory” TME and synergy with cytotoxic chemotherapy or other partners. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Azacitidine at low doses serves as an epigenetic modifier by regulating DNA methylation, whereas at higher doses it can be directly cytotoxic. Ruan et al administered oral azacitidine (CC-486) prior to each cycle of cytotoxic CHOP therapy in PTCL. When examining pharmacodynamic effects on 5 paired tumor samples, they observed differential gene expression before and after CC-486 administration in gene sets related to inflammatory response and hypoxia, suggesting a favorable change in the composition of the tumor microenvironment (TME) facilitated by CC-486. Furthermore, gene-based cell subtype deconvolution showed a trend towards lower TFH lymphoma cells and proliferation suggesting a possible directly antineoplastic effect on malignant T cells, particularly TFH cells. Although the exact mechanisms of the potentially chemosensitizing changes remain to be further elucidated, epigenetic priming may lead to a favorably disposed and likely more “inflammatory” TME and synergy with cytotoxic chemotherapy or other partners. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

The observed responses and survival following Aza-CHOP are encouraging when compared with historic data with CHOP alone2,3 and underpin the promising potential of combining epigenetic agents with cytotoxic therapy, particularly in nTFHL. Although the described outcomes surpass expectations for PTCL, a select study population and small sample size limit generalizability. Nevertheless, the well-designed correlative studies allow an insight into the potentially sensitizing effect of epigenetic priming on the tumor microenvironment, which paves the way for the ongoing randomized ALLIANCE-led A051902 phase 2 study that includes Aza-CHOP as 1 investigational arm (NCT04803201).

Although a similar approach of combining epigenetic therapy with cytotoxics by adding the HDACi romidepsin to a CHOP backbone (Ro-CHOP) did not meet its predefined endpoint of improvement in PFS, the results of that study may have been different if designed to only allow participants with nTFHL pathology. In this phase 3 randomized clinical trial for newly diagnosed aggressive T-cell lymphomas, an exploratory analysis showed a significantly prolonged PFS for Ro-CHOP compared with CHOP only in the nTFHL subset but not for the entire study population.9 Multiple recent “negative studies” have dampened the enthusiasm for developing new agents in PTCL, with progress further impeded by the rarity of this orphan disease and its significant heterogeneity. A likely culprit for the lack of progress in treatment is a 1-size fits all approach, highlighting the importance of studies that are well designed based on our current understanding of disease pathobiology and that include well-planned correlatives. Efforts to develop personalized therapies based on specific disease characteristics require identifying predictive biomarkers. Although outcomes for PTCL have been largely stagnant for the past 2 decades, the notable exception has been a biomarker-driven treatment using CD30-targeted therapy in CD30+ PTCL. In Echelon-2, the addition of the CD30-directed antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin to cytotoxic therapy led to a survival benefit, specifically for participants with anaplastic large cell lymphoma.10 In their article, Ruan et al present results supporting using the nTFHL phenotype and TET2 mutations as possible predictive biomarkers for selecting patients for Aza-CHOP.

In conclusion, new insights into pathobiology have not only resulted in deeper understanding and better classification of T-cell lymphomas but also promise to finally allow us to improve therapy on CHOP. Cytotoxic therapy alone has consistently let us down in the management of T-cell lymphoma, and this study offers a glimpse into how selecting therapy based on the biologic characteristics of the lymphoma should lead to improvements in T-cell lymphoma upfront therapy. Epigenetic therapy has the potential to move the bar, especially if combined rationally with appropriate partners.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author is on the advisory committees of and receives honoraria from Acrotech, Affimed, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, and Seagen.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal