In this issue of Blood, van der Straten et al1 report that frailty, as measured by geriatric assessment (GA) in older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), is likely to improve with targeted drug therapy. This observation was based on the HOVON139/GiVe trial, in which 67 mostly older patients (median age, 71 years) who were unfit for chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab received 12 cycles of chemotherapy-free treatment with venetoclax/obinutuzumab (Ven-O) followed by prolonged venetoclax consolidation.2

People who develop CLL are often aged ≥70 years, and most present with comorbidities and/or geriatric conditions (eg, mobility issues, cognitive decline, and mood problems). Such geriatric impairments predispose patients to increased vulnerability (frailty) to adverse health events, including worsening of these conditions.3-5 In older patients with solid or hematological malignancies, such as CLL, GA is recommended before initiating drug therapy.6,7 The rationale is to identify age-associated vulnerabilities that increase the risk of toxicity and, in case of increased frailty, the general recommendation is to reduce the intensity of drug treatment. Currently, the antileukemic treatments for this patient group are Ven-O, venetoclax/ibrutinib, and ibrutinib or acalabrutinib alone.8

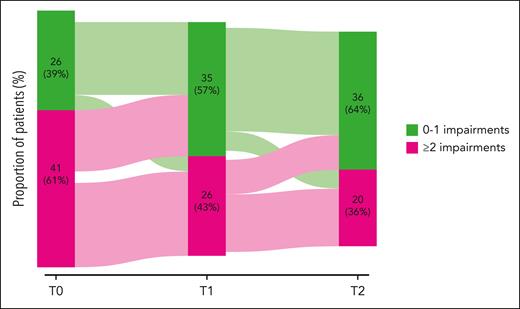

HOVON139/GiVe is the first trial to comprehensively examine GA and frailty in the context of modern targeted CLL drug therapy. The study confirms several phenomena that were already well established for other hematological malignancies5: Specifically, although virtually all study participants had a very good or good Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), most (61%) had >1 one geriatric impairment identified by GA. Not surprisingly, these patients were at higher risk of grade ≥3 nonhematological toxicity. Conversely, the study results challenge the general paradigm of de-escalating therapy in the case of increased frailty: Despite poorer tolerability of the treatment, patients with increased frailty attributable to the presence of >1 geriatric impairment mainly showed improvement by decreasing their overall geriatric burden over the course of Ven-O therapy. In fact, more than half of the patients with an initially high geriatric burden converted to a later low one (see figure). Furthermore, most of these patients with a high geriatric burden experienced similar improvements in quality of life over time as patients with a low baseline geriatric burden. These are important observations from which we conclude that the surrogates used to gage frailty by GA in CLL at baseline, such as reduced walking speed, loss of strength, and nutritional problems, are not only caused by aging and chronic comorbidity, but are also driven by the underlying hematological disease itself. These geriatric impairments thus contribute to the overall level of frailty but, more important, are responsive to antileukemic treatment, including targeted CLL drugs.

Targeted drug therapy of CLL with Ven-O is associated with a reduction in the number of geriatric conditions as a surrogate of frailty. See Figure 2B in the article by van der Straten et al that begins on page 1131.

Targeted drug therapy of CLL with Ven-O is associated with a reduction in the number of geriatric conditions as a surrogate of frailty. See Figure 2B in the article by van der Straten et al that begins on page 1131.

So, should we no longer include a GA in older adults with CLL and no longer consider frailty in this setting because frailty appears to be improving rather than worsening with targeted CLL therapy? There are several reasons not to do this, but rather to further investigate frailty and the utility of GA in CLL. For example, the study results reported by van der Straten et al do not answer the question of whether very old patients (aged ≥80 years) or older patients with poor performance status (ECOG PS 2-3) will experience the same benefit from Ven-O in terms of reducing geriatric burden. Furthermore, the findings in this study need to validated using other drugs. One cannot safely conclude that frailty surrogates measured by GA will undergo the same positive changes using targeted therapy with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Finally, recent randomized controlled trials have shown that geriatric conditions and thus frailty can also be combated by GA-led geriatric interventions during systemic cancer therapy (eg, physical exercise, nutritional support, and polypharmacy management).9,10 We do not yet know whether this can further reduce geriatric burden and frailty in older patients with CLL, in addition to gains from targeted drug therapy for CLL.

The study’s finding that targeted drug treatment of CLL helps to combat frailty should encourage us to better address 2 needs in CLL trials enrolling older patients: First, geriatric burden and frailty of trial participants at baseline should be captured and described not only by age, ECOG PS, and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, but also by GA. Second, in addition to common hematological end points, such as response, adverse events, and survival, the geriatric burden and frailty should be analyzed by longitudinal GA measurements and reported as an outcome of the treatment. If this is omitted, highly relevant benefits of modern drug-based CLL therapy for older patients might not be recognized. The reported results of HOVON139/GiVe on GA also provide a rationale for integrating GA into routine care. This can help to identify older patients at increased risk of nonhematological toxicity and, specifically, to provide guidance when planning targeted drug therapy for CLL with Ven-O.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: V.G. has received speaker’s and/or consultancy fees from Novartis, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Janssen, Gilead, Roche, Mundipharma, Bristol-Myers, Heel, and Berlin Chemie.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal