In this issue of Blood,1Senapati et al suggest that recurrent mutations in genes encoding RNA splicing factors may not confer an adverse prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated with venetoclax-based therapies.

In many blood cancers, acquired recurrent genetic changes are used as prognostic biomarkers. As biomarkers, these changes often form the basis of prognostic classifications for newly diagnosed patients that can dictate their treatment. As an exemplar, the commonly used European LeukemiaNet (ELN) recommendations on the diagnosis and management of AML include a classification of prognostic risk, with 3 prognostic groups (favorable, intermediate, and adverse).2,3 These recommendations are widely used to guide discussions with patients on prognosis and treatment. In the revised 2022 recommendations, it was recognized that recurrent genetic mutations commonly seen in myelodysplasia correlate with an adverse outcome.3 This was true regardless of whether the patient had an antecedent clinical history of myelodysplasia or had myelodysplastic-related cytogenetic changes in their AML cells. These myelodysplastic-related gene mutations included those in genes encoding the RNA splicing factors SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 (hereafter referred to as splicing factor mutations, or SFmut). However, a caveat with the ELN risk classification is that it has been developed with data from patients treated with intensive combination chemotherapy. As the incidence of myelodysplastic-related gene mutations increases with age, AML patients with these mutations are likely to be older and more likely to receive venetoclax and hypomethylating agents (HMA).4 This raises the obvious, and clinically important, question of whether the ELN risk classification applies to the majority of patients with SFmut who are treated with venetoclax-based, lower-intensity treatments and not intensive combination chemotherapy.

To address this question, Senapati et al examined the clinical outcome of 994 newly diagnosed AML patients treated between 2017 and 2022 from a single tertiary referral institution. The patients had extensive molecular and cytogenetic data at diagnosis. The median follow-up for the cohort was 26 months. Sixty-six of 994 patients with core-binding factor AML were excluded from the analysis; 928 patients were studied for most of the analyses. Of those, 266 patients had SFmut and 662 patients did not have splicing factor mutations (hereafter referred to as SFwt). Overall, the SFmut and SFwt groups were not matched for age, cytogenetics, ELN high-risk mutations besides mutations in genes encoding splicing factors (TP53, RUNX1, and ASXL1), and incidence of secondary and therapy-related AML. Of the 928 patients, 617 received lower-intensity treatments and 311 were treated with higher-intensity regimens. There was considerably heterogeneity with respect to treatment (up to 46 different treatments were given, but venetoclax-HMA-based treatments were most common among lower-intensity treatments).

Given the heterogeneous and retrospective nature of this cohort coupled with imbalances in risk factors between the SFmut and SFwt, analyses of these data need to be interpreted with caution. Starting first with patients who received intensive combination chemotherapy, the authors confirmed that SFmut patients (53/662) compared with SFwt patients (258/662) had an inferior overall survival (15.9 months compared with 26.7 months; P = .06) and relapse-free survival (9.6 months compared with 21.4 months; P = .04). However, when they examined patient groups who had received venetoclax combined with combination chemotherapy (29/53 SFmut and 131/258 SFwt patients), the difference in overall survival and relapse-free survival between SFmut and SFwt patients disappeared. This was the first hint that addition of venetoclax (ie, treatment change) may alter the prognostic impact of SFmut.

Turning to patients who received lower-intensity treatments, the authors conducted a number of analyses, such as on patients above and below the age of 60 and comparing patients with de novo AML with those with a clinical history of therapy-associated AML and secondary AML, and in both cases stratifying patients by whether they received venetoclax or not in their treatment schedules. The clinical outcomes that were compared were overall survival and relapse-free survival. In all analyses, SFmut was not associated with an adverse outcome. To pick an example of these analyses in patients over the age of 60 years, who more commonly receive lower-intensity treatment, overall survival and relapse survival in the SFmut and SFwt patient groups were 12.3 months versus 8.5 months and 9.3 months versus 7.7 months, respectively. In patients who received venetoclax as part of lower-intensity therapy, overall survival and relapse survival in SFmut and SFwt patient groups were 14.1 months versus 9.6 months and 9.8 months versus 9.1 months, respectively. In univariate analysis and multivariate analysis, SFmut did not affect attainment of overall response in both intensively treated patients and patients who received lower-intensity treatments. Finally, Cox regression analysis was used to identify factors predictive of survival in prestratified groups. In patients older than 60 treated with lower-intensity regimens, on univariate analysis SFmut did not affect the hazard of relapse or overall survival. This was also true in multivariate analysis. By contrast, in both univariate and multivariate analyses, the ELN 2017 adverse-risk category (which includes a number of poor-risk cytogenetic subgroups and mutations in the genes encoding TP53, RUNX1, and ASXL1 but not SFmut) was associated with significantly poorer overall survival and relapse-free survival, whereas addition of venetoclax to therapy and stem cell transplant was associated with improved overall survival and relapse-free survival.

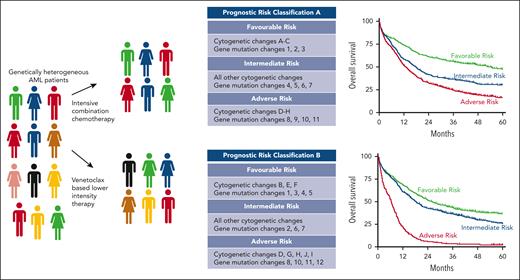

As mentioned previously, though these data have important caveats and need to be validated, they remind us that any prognostic biomarkers need to be assessed in the context of the treatment given (see figure). Most clinicians would agree this is self-evident, but the data from Senapati and colleagues are a timely reminder of this truism. Specifically, in AML, where the standard of care has changed for most patients with SFmut to venetoclax-based lower-intensity regimens, the field needs to agree on a new validated prognostic classification for this group of patients as a priority. Progress on this front is beginning.5

Frontline treatment of a genetically heterogeneous group of patients newly diagnosed with AML who received either intensive combination chemotherapy or venetoclax-based lower-intensity therapy. Treatment- and patient-specific factors will determine the prognostic biomarkers that may differ between treatment groups (middle panel), which produce survival curves relevant to each treatment group.

Frontline treatment of a genetically heterogeneous group of patients newly diagnosed with AML who received either intensive combination chemotherapy or venetoclax-based lower-intensity therapy. Treatment- and patient-specific factors will determine the prognostic biomarkers that may differ between treatment groups (middle panel), which produce survival curves relevant to each treatment group.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal