Abstract

Given the shortcomings of current factor-, nonfactor-, and adeno-associated virus gene–based therapies, the recent advent of RNA-based therapeutics for hemophilia is changing the fundamental approach to hemophilia management. From small interfering RNA therapeutics that knockdown clot regulators antithrombin, protein S, and heparin cofactor II, to CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing that may personalize treatment, improved technologies have the potential to reduce bleeds and factor use and avoid inhibitor formation. These novel agents, some in preclinical studies and others in early phase trials, have the potential to simplify treatment and improve hemostasis and quality of life. Furthermore, because these therapies arise from manipulation of the coagulation cascade and thrombin generation and its regulation, they will enhance our understanding of hemostasis and thrombosis and ultimately lead to better therapies for children and adults with inherited bleeding disorders. What does the future hold? With the development of novel preclinical technologies at the bench, there will be fewer joint bleeds, debilitating joint disease, orthopedic surgery, and improved physical and mental health, which were not previously possible. In this review, we identify current limitations of treatment and progress in the development of novel RNA therapeutics, including messenger RNA nanoparticle delivery and gene editing for the treatment of hemophilia.

Introduction

Novel nonfactor therapeutics, including gene therapy, have revolutionized the management of hemophilia A and B (HA and HB, respectively). Despite the impact of these agents to simplify dosing strategies and improve clinical outcomes, complications dampen the enthusiasm of implementing current therapies. Recent innovations in RNA-based therapeutics are fundamentally changing the approach to hemophilia treatment. The goal of this review is to focus on new RNA-based therapeutics for hemophilia and mechanisms by which they enhance treatment.

The hemophilias are congenital, X-linked, monogenic disorders caused by mutations in the genes encoding factor VIII (FVIII) or FIX gene. The deficiencies of FVIII, HA, or clotting FIX, HB result in spontaneous and traumatic bleeding into joints, muscles, and the central nervous system.1,2 Although effective, clotting factor replacement is invasive and complicated by inhibitors in up to 30% of patients.1,2 Evolving treatment goals are to achieve higher factor trough levels to allow a more active lifestyle and reduce the fear of bleeds.3 This has been achieved with the novel FVIII–von Willebrand factor fusion protein, efanesoctocog α, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HA, which achieves FVIII trough levels from 12% to 15%.4 In individuals who have HA with FVIII inhibitors, for whom FVIII products are ineffective, the nonfactor, FDA-approved bispecific monoclonal antibody, emicizumab, has effectively reduced bleeding events and greatly simplified administration, because it is given subcutaneously.5,6 Because emicizumab prevents but does not treat acute bleeds, concomitant factor is required for acute bleeds. However, the concomitant use of factor products, primarily the bypass agent FEIBA (factor eight inhibitor bypass activity), with emicizumab, may lead to life-threatening thrombosis, some cases being fatal,7,8 for which there is a boxed safety warning to underscore the significance of this risk. Thus, for patients with HA inhibitor receiving emicizumab prophylaxis, FEIBA is limited or avoided, with preferential use of recombinant factor VIIa to treat acute bleeds. Because of these limitations, there has been interest in simpler, safer therapies for hemophilia.

With the recent approval of adeno-associated virus (AAV)–based gene therapy for hemophilia this year, valoctocogene roxaparvovec for HA9 by the European Union and etranacogene dezaparvovec for HB10 by the FDA, progress continues toward phenotypic cure; however, this enthusiasm is dampened because of the decline in factor expression over time.9 Although these AAV-based gene therapeutics, which target the liver, have achieved long-term factor levels in the mild hemophilia ranging from ∼10% to 15% or higher and having greatly reduced clinical bleeding rates, the durability of expression remains unknown. AAV vectors encoding F8 and F9 transgenes have demonstrated single-dose efficacy for up to 5 years in patients with HA, up to 10 years in patients with HB, and up to 12 years in nonhuman primates. However, AAV gene therapy has been limited by transaminase elevation because of AAV capsid immunogenicity, waning durability, and variability of expression.11 Furthermore, children, patients with inhibitor, and individuals who have been previously exposed to AAV remain ineligible for gene therapy. Better approaches are, therefore, needed.

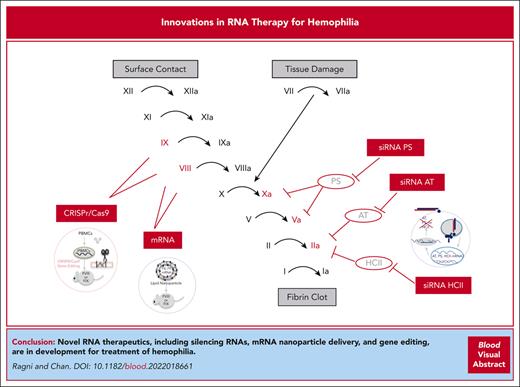

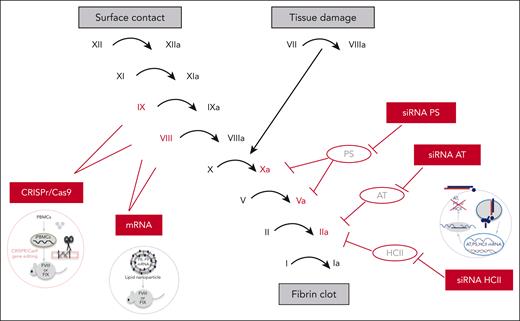

The advent of RNA-based therapeutics has provided the basis for novel alternatives to factor-, nonfactor-, and gene-based therapies for hemophilia (Table 1). Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) delivered subcutaneously that knockdown clot inhibitors antithrombin (AT) and protein S (PS) are in early and late phase studies. Other RNA-based therapies delivered via a single infusion include messenger RNA (mRNA) nanoparticle delivery and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and associated Cas9 endonuclease (CRISPR/Cas9) gene editing. Moreover, much work remains to bring these therapeutics to the clinical setting. If successful, these agents provide unique advantages in being versatile, having quickengineering and deployment action, and being potentially better tolerated and less restrictive based on age, AAV, and inhibitor status than current therapies while, at the same time, enhancing our understanding of the coagulation and immune systems (Figure 1).

RNA therapeutics for hemophilia

| Agent . | Mechanism . | Route, frequency . | Trial status . | Target group . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA antithrombin fitusiran | AT mRNA silencing | Subcutaneous, monthly or bimonthly | Phase 1, 2, and 3 trials | HA and HB with or without inhibitors |

| siRNA PS | PS mRNA silencing | Subcutaneous | No trials to date | HA and HB with or without inhibitors |

| siRNA HCII | HCII mRNA silencing | Subcutaneous | No trials to date | HA mouse studies |

| mRNA gene therapy | Lipid-encapsulated mRNA by intracellular delivery, or transposon | IV single dose | No trials to date | HA and HB |

| Gene editing ZFN or CRISPR/Cas9 | Nuclease-driven homology-directed gene repair | IV single dose | No trials to date | HA and HB |

| Agent . | Mechanism . | Route, frequency . | Trial status . | Target group . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA antithrombin fitusiran | AT mRNA silencing | Subcutaneous, monthly or bimonthly | Phase 1, 2, and 3 trials | HA and HB with or without inhibitors |

| siRNA PS | PS mRNA silencing | Subcutaneous | No trials to date | HA and HB with or without inhibitors |

| siRNA HCII | HCII mRNA silencing | Subcutaneous | No trials to date | HA mouse studies |

| mRNA gene therapy | Lipid-encapsulated mRNA by intracellular delivery, or transposon | IV single dose | No trials to date | HA and HB |

| Gene editing ZFN or CRISPR/Cas9 | Nuclease-driven homology-directed gene repair | IV single dose | No trials to date | HA and HB |

RNA therapeutics for hemophilia. Sites of action of RNA therapeutics in the coagulation cascade. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and mRNA therapeutics target the genes encoding FVIII and FIX in the intrinsic coagulation pathway. The siRNAs target natural coagulation inhibitors of factors in the common coagulation pathway (FIIa, FVa, and FXa), including AT (siRNA AT), siRNA PS, and siRNA HCII.

RNA therapeutics for hemophilia. Sites of action of RNA therapeutics in the coagulation cascade. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and mRNA therapeutics target the genes encoding FVIII and FIX in the intrinsic coagulation pathway. The siRNAs target natural coagulation inhibitors of factors in the common coagulation pathway (FIIa, FVa, and FXa), including AT (siRNA AT), siRNA PS, and siRNA HCII.

siRNA therapeutics

It has been long known that individuals with hemophilia who have concomitant prothrombotic mutations, including AT deficiency, protein C deficiency, PS deficiency, or FV leiden mutation, have more moderate bleeding phenotypes.12,13 This observation along with the evolution of RNA-based therapeutics led to interest in the potential of creating a relative deficiency in a natural clot inhibitor as an approach to reduce the severity of bleeding in hemophilia. The concept of RNA interference (RNAi) by small interfering double-stranded RNAs to silence posttranscriptional genes was first recognized by Fire et al in 1998, with a double-stranded RNA in nematodes.14 Teleologically, RNAi is a natural mechanism by which small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) silence repetitive genes or foreign viruses. The application of siRNAs to interference with mRNA translation has the potential to negatively regulate gene expression via recognition and binding target transcript sequences. Engagement of interfering RNA molecules with target RNA transcripts can degrade mRNAs and/or their translation, thereby resulting in effective gene silencing. Given the relative ease of engineering interfering RNA molecules with the specific targeting sequence of interest, this mechanism carries versatility in its therapeutic potential to silence any transcript across the transcriptome.15,16 The therapeutic advantage includes relative specificity of target engagement with predictably high efficiency in gene silencing, and in contrast to AAV technology, immunogenicity is not a concern with this method. Thus far, target transcripts are primarily expressed in the liver, given the predilection for endogenous siRNA uptake into hepatic tissue after administration. Rapid application of this technology has advanced to FDA-approved treatment across cardiovascular, metabolic, and hepatic diseases,17 with anticipated application to infectious, oncologic, and neurodegenerative diseases. As such, RNA-mediated suppression of transcripts encoding for liver-derived clot inhibitors18 is an attractive therapeutic approach to treat hemophilia.19 An important step in the development of siRNA therapy for hemophilia was the identification of potential targets AT and PS (Figure 1).

siRNA AT

AT is a glycoprotein and member of the serine protease inhibitor (serpin) family.

It binds to and inhibits thrombin (IIa), a key multifunctional enzyme in blood coagulation, which activates platelets and other coagulation factors (VIIII, V, XI, and XIII) and converts fibrinogen to fibrin, the final clot. The importance of AT is underscored by the well-recognized occurrence of thrombosis in individuals with AT deficiency and the reduced bleeding severity in individuals with severe hemophilia with concomitant AT deficiency.13,14 To target AT, which is synthesized in the liver, the siRNA is conjugated to N-acetyl-galactosamine to improve hepatocyte binding via the asialoglycoprotein (ASPGR) receptor and protect it from nuclease breakdown.20 Using this approach, Sehgal et al found that subcutaneous injection of siRNA AT in wild-type mice and a HA mouse models suppressed AT synthesis, and in wild-type and a nonhuman primate model of HA with anti-FVIII antibodies, it demonstrated a dose-dependent correction of the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and thrombin generation and bleeding reduction.21 In phase 1 trials, monthly subcutaneous siRNA AT (fitusiran) showed dose-dependent reduction of AT in HA or HB without22 or with inhibitors,23 confirming that 75% AT reduction was safe (Table 2), and phase 3 studies found bleeding rates comparable with those of prophylaxis with factor or bypass agents, with improved quality of life.24-27 Surgical management required, in addition to fitusiran, the concomitant use of reduced dose and frequency factor or bypass agent with good hemostasis, similar to that of patients who were unaffected.28 The most common adverse effect besides mild injection-site reactions and, infrequently, cholecystitis has been asymptomatic liver function test elevation, which may represent off-target effects of an siRNA directed at the liver.29 Off-target effects are attributed to the binding of nucleotides, in the seed region of the siRNA guide strand, to complementary sites encoded in the 3′ untranslated region of nontargeted mRNA transcripts. Theoretically, as tested in preclinical models, this off-target effect could be mitigated by incorporating thermal destabilizing chemical modifications in the seed region of the guide strand, thus prioritizing on-target activity and minimizing hepatotoxicity.29,30

Fitusiran clinical trials in HA and HB with and without inhibitors

| Fitusiran trials . | Subjects . | No. . | Dose, frequency . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | ||||

| NCT0203560522 | HA and HB | N = 25 | 80 mg mo | AT reduction, 70%-89% |

| Phase 2 | ||||

| NCT0255477324 | HA and HB HA-I and HB-I | N = 14 N = 13 | 50 or 80 mg mo | Haem-A-QoL total score = −8.33 Haem-A-QoL total score = −9.16 |

| Phase 3 | ||||

| NCT0341724525,26 | HA and HB | N = 120 | 80 mg SQ mo | ABR reduced 89.9% vs OD-factor Factor use reduced 94.7%-95.9% |

| NCT0341710225,26 | HA-I and HB-I | N = 60 | 80 mg SQ mo | ABR reduced 90.8% vs OD-BPA Factor use reduced 97.5%-98.2% |

| NCT0354987127 | HA-I and HB-I | N = 65 | 80 mg SQ mo | HRQoL score = −4.6, SAE = 13.4% |

| Surgical28 | ||||

| NCT0203560522 NCT0255477324 | HA and HB HA-I and HB-I | N = 13 | 50 or 80 mg mo Lower dose CFC, BPA, tapering early | In 17 surgeries (11 major and 6 minor), blood loss was minimal or similar to that of individuals who were nonhemophilic |

| Fitusiran trials . | Subjects . | No. . | Dose, frequency . | Results . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | ||||

| NCT0203560522 | HA and HB | N = 25 | 80 mg mo | AT reduction, 70%-89% |

| Phase 2 | ||||

| NCT0255477324 | HA and HB HA-I and HB-I | N = 14 N = 13 | 50 or 80 mg mo | Haem-A-QoL total score = −8.33 Haem-A-QoL total score = −9.16 |

| Phase 3 | ||||

| NCT0341724525,26 | HA and HB | N = 120 | 80 mg SQ mo | ABR reduced 89.9% vs OD-factor Factor use reduced 94.7%-95.9% |

| NCT0341710225,26 | HA-I and HB-I | N = 60 | 80 mg SQ mo | ABR reduced 90.8% vs OD-BPA Factor use reduced 97.5%-98.2% |

| NCT0354987127 | HA-I and HB-I | N = 65 | 80 mg SQ mo | HRQoL score = −4.6, SAE = 13.4% |

| Surgical28 | ||||

| NCT0203560522 NCT0255477324 | HA and HB HA-I and HB-I | N = 13 | 50 or 80 mg mo Lower dose CFC, BPA, tapering early | In 17 surgeries (11 major and 6 minor), blood loss was minimal or similar to that of individuals who were nonhemophilic |

ABR, annualized bleed rate; BPA, bypassing agent; CFC, clotting factor concentrate; Haem-A-QoL, hemophilia A quality of life; HA-I, HA with inhibitor; HB-I, HB with inhibitor; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; OD, on-demand; SAE, serious adverse events; SQ, subcutaneous.

During phase 2 trials, arterial and venous thrombosis unexpectedly occurred, including cerebral infarct, cerebrovascular accident, spinal vascular thrombosis, atrial thrombosis, and cerebral sinus thrombosis, some being fatal.9,31,32 Alhough the use of concomitant factor or bypass agents for acute bleeds did occur in some patients who developed thrombosis, an AT level <20% was the most significant risk factor for thrombosis. In fact, no thrombosis occurred in those with AT levels >20%. For this reason, in addition to minimizing dose and frequency of concomitant factor, an overall reduction in dose and frequency of fitusiran to maintain AT levels >20% was instituted, which has been successful, to date, in avoiding thrombosis.9,31

siRNA PS

Another siRNA therapeutic in development to treat hemophilia is siRNA PS. PS is a natural anticoagulant and is required as a cofactor for 2 other natural anticoagulants, activated protein C and tissue factor pathway inhibitor α.33 The clinical importance of PS is the recognized occurrence of thrombosis in patients with PS deficiency,34 reduction in bleeding by tail clip in mice with HA and HB lacking PS, and improved thrombin generation in plasma of patients with hemophilia in whom PS was blocked using a monoclonal antibody.35 These observations encouraged the development of PS inhibition in preclinical studies.

Prince et al administered siRNA PS to mice with HA and demonstrated that PS reduction correlated with improved clot formation viaby rotational thromboelastometry and reduced intraarticular bleeding in a needle-induced hemarthrosis model.36 Studies of platelet-free plasma of patients with HA, to which anti-PS antibodies were added to simulate concomitant PS deficiency, demonstrated a 45% reduction in PS and increased peak thrombin generation.37 Subsequently, this group studied a nonhuman primate model of acquired HA, induced using an IV injection of anti-FVIII antibody, resulting in <0.5% FVIII activity. Then, after a single subcutaneous dose of the anti-PS antibody in this acquired HA model, there was restoration of normal thrombin potential.37 These studies suggest the potential of siRNA PS as a therapeutic for HA.

siRNA HCII

A third potential target for siRNA silencing is the natural anticoagulant heparin cofactor II (HCII), a 42 amino acid serine protease that inhibits thrombin.38 Aproximately 10% as efficient as AT in thrombin inhibition, HCII activity is enhanced by glycosaminoglycans, for example, dermatan sulfate in a vessel wall plays a primary role in connective tissue and vessel injury. The clinical significance of HCII is the association of HCII deficiency with thrombosis39 and shortened time to thrombus after vascular injury.40

Based on this profile, HCII was identified as a therapeutic target for HA. The administration of siRNA HCII via subcutaneous injection in healthy mice resulted in dose-dependent knockdown of HCII levels. In mouse with HA, after siRNA HCII injection, the APTT and bleeding time were shortened in tail clip assay.41 Furthermore, siRNA HCII significantly promoted thrombin generation and improved hemostasis in mice with HA after ferric chloride–induced carotid artery injury.41 Importantly, at high dose, acute hepatotoxicity was observed, which may reflect siRNA off-target effects. No thrombosis occurred even with repeated high dosing, and no pathologic thrombus was present in organs examined.

These preclinical findings demonstrate that siRNA HCII improves hemostasis and reduces thrombotic potential in mice with HA, suggesting its potential for development as a HA therapeutic.

Nonviral vector gene therapy

Modified mRNA gene therapy

The development of mRNA as a therapeutic approach for hemophilia has evolved as an important alternative to vector-based gene therapies. It poses no risk of integration, is efficiently transported to liver cells, can be administered weekly, is less immunogenic, and is less costly than clotting factors. Development of modified mRNA therapies was recently accelerated by the successful deployment of mRNA vaccines in the COVID-19 pandemic.42 Unlike mRNA vaccine technology, though, modified mRNA gene therapy for hemophilia would require higher gene expression and more frequent dosing. Furthermore, the use of synthetic mRNAs is limited by rapid degradation in vivo, and immunogenicity may occur with repeated dosing. The development of lipid nanoparticles, however, has greatly enabled the use of mRNA, because it protects mRNA from degradation. Lipid nanoparticles are easy to prepare, biocompatible, and, in contrast to vector-based therapy, cause no insertional mutagenesis. They have become the most common nonviral vectors, including in hemophilia models (Table 3).

mRNA gene delivery studies in hemophilia

| Study . | Lipid delivery . | Target cell . | Recipient . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F9 mRNA43 Padua-9 mRNA Ramaswamy, 2017 | LUNAR lipid nanoparticle | Hepatocyte with luciferase reporter | IV injection in mice with HB | Peak FIX 130% with Padua IX and peak FIX 20% with FIX Levels: 4-9 d vs 1-3 d No inhibitor formation No LFT abnormalities |

| BDD-F8 mRNA44 Russick, 2020 | Lipid nanoparticle | HEK293 cells with luciferase reporter | IV injection in mice with HA | Peak FVIII, 0.36 IU/mL at 24 h FVIII, 0.06-0.11 IU/mL at 72 h Reduced blood loss in tail clip Inhibitor with repeat dosing |

| BDD-F8 mRNA45 Chen, 2020 | Lipid nanoparticle | Hepatocyte with luciferase reporter | IV injection in mice with HA and NSG mice with HA | FVIII activity 5-7 days and APTT and ROTEM corrected Inhibitors formed in mice with HA, but not mice with NSG HA |

| F8 mRNA46 Truong, 2022 | Nanoparticle, transposon nanoparticle | Hepatocyte | PiggyBac GT in neonatal wild-type mice; mice with CD4-HA | FVIII:Ag expressed >50% and sustained 5 months in wild-type mice FVIII activity 30%-150% level and sustained 6 months in mice with HA |

| Study . | Lipid delivery . | Target cell . | Recipient . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F9 mRNA43 Padua-9 mRNA Ramaswamy, 2017 | LUNAR lipid nanoparticle | Hepatocyte with luciferase reporter | IV injection in mice with HB | Peak FIX 130% with Padua IX and peak FIX 20% with FIX Levels: 4-9 d vs 1-3 d No inhibitor formation No LFT abnormalities |

| BDD-F8 mRNA44 Russick, 2020 | Lipid nanoparticle | HEK293 cells with luciferase reporter | IV injection in mice with HA | Peak FVIII, 0.36 IU/mL at 24 h FVIII, 0.06-0.11 IU/mL at 72 h Reduced blood loss in tail clip Inhibitor with repeat dosing |

| BDD-F8 mRNA45 Chen, 2020 | Lipid nanoparticle | Hepatocyte with luciferase reporter | IV injection in mice with HA and NSG mice with HA | FVIII activity 5-7 days and APTT and ROTEM corrected Inhibitors formed in mice with HA, but not mice with NSG HA |

| F8 mRNA46 Truong, 2022 | Nanoparticle, transposon nanoparticle | Hepatocyte | PiggyBac GT in neonatal wild-type mice; mice with CD4-HA | FVIII:Ag expressed >50% and sustained 5 months in wild-type mice FVIII activity 30%-150% level and sustained 6 months in mice with HA |

CD117, stem cell factor receptor; Cre recombinase, conditional control of gene expression; FVIII:Ag, factor VIII antigen; HSC, hematopoietic stem cells; LFTs, liver function tests; ROTEM, rotational thromboelastometry.

mRNA FIX delivery

An approach that uses a LUNAR (lipid enabled and unlocked nucleic acid-modified RNA) system has successfully delivered FIX mRNA IV in the HB mouse model.43 This system uses 4 lipid components and an acidic ionizable amino group to encapsulate the negatively charged RNA, thereby promoting the formation of neutrally charged nanoparticles which improve mRNA stability. In this model the LUNAR delivery system prevented liver toxicity and, importantly, immunogenicity on repeated dosing. Delivery of the padua IX gene in the HB model resulted in peak IX activity of 130% for 4 or 9 days, with no inhibitors on repeated dosing and no liver dysfunction.44

mRNA FVIII delivery

In studies by Russick et al, a single injection of in vitro–transcribed mRNA for B domain deleted (BDD)-FVIII, packaged in TransIT mRNA reagent, was administered to mice with HA. This resulted in peak FVIII levels of 36%, persisting >5% for 72 hours, sufficient to prevent bleeding in a tail clip assay.44 This delivery system, however, was complicated by inhibitor formation, attributed to the greater immunogenicity of the FVIII protein and the sixfold greater amount of FVIII delivered by F8 mRNA than by FVIII clotting factor. Inhibitors also complicated lipid nanoparticle delivery of BDD F8 mRNA to hepatocytes in mice with HA, which as expected, was prevented in the immunosuppressed HA NSG mice model.45

F8 mRNA has also been delivered to hepatocytes via Super piggyBac (SPB) transposase mRNA. An SPB transposase mRNA encapsulated in a liver-tropic nanoparticle was used to deliver F8 IV to wild-type mice. This resulted in rapid FVIII expression but was durable for only a few days.46 However, when an SPB transposase nanoparticle mRNA was coadministered, as part of a dual nanoparticle system with a human FVIII transposon nanoparticle, sustained therapeutic FVIII expression persisted for 5 months. When this dual nanoparticle system was administered to mice with HA, peak FVIII levels from 30% to 150% were detectable for 6 months with no inhibitor development. Although this approach enables stable integration and FVIII expression sufficient to avoid FVIII immunogenicity, it has the same inherent risks of genomic insertion as retroviral or lentiviral vectors. Nonetheless, it remains a promising approach for the future development of FVIII mRNA as a hemophilia therapeutic. Future work will focus on identifying simpler, more efficient lipid nanoparticle mRNA delivery.

Gene editing

Although liver-directed AAV gene therapy has been successfully performed in humans, transgene expression may be limited by physiologic proliferation of the liver or, in the case of HA, by decline in expression over time of unclear etiology. An alternative to viral vector–delivered gene therapy approaches is in vivo gene editing. Gene editing enables direct modification of an animal or human genome at a specific locus via the use of a nuclease, such as zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) or CRISPR/Cas9 system.47 Of these, the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is currently the most compelling because of its simplicity, low cost, and efficacy,48 yet more advanced systems of editing, such as base and prime editing, are developing quickly.

Gene editing in proliferating cells provides the potential to treat children and avoids off-target integration and immune response to even transient Cas9 protein exposure. CRISPR/Cas9 is composed of a guide RNA to locate the loci of interest within the genome and a Cas9 nuclease to induce a double-stranded break in the DNA.47,48 This system allows for ex vivo editing of patient-derived cells via gene correction, disruption, or addition, after which the break is repaired via nonhomologous end joining or homologous direct repair, and the corrected cells are transplanted or infused into an animal model. ZFN and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing of defective F9 or F8 genes have been studied primarily in induced pluripotential stem cells (iPSCs), which are nonimmunogenic and avoid rejection because they are obtained from and returned to a single individual. ZFN and CRISPR/Cas9 systems have been assessed in several preclinical hemophilia models (Table 4).

Gene editing studies in hemophilia

| Gene targeted . | Cell type . | Gene editing . | Nuclease delivery . | Donor . | Results in recipient model . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemophilia B | |||||

| F949 Li, 2011 | Hepatocytes | Gene correction | ZFN via plasmid and AAV delivery system | DNA | Correction of FIX in neonatal HB mouse model |

| F950 Anguela, 2013 | Hepatocytes | Gene correction | ZFN via plasmid and AAV delivery system | DNA | Correction of FIX in adult HB mouse model |

| F951 Lyu, 2018 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid electroporation | Plasmid | FIX secreted in transplanted HB mouse |

| F952 Ramaswamy, 2018 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas 9 plasmid nucleofection | DNA | Correction of FIX in HLCs in HB mouse |

| F9353 Morishige, 2020 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 plasmid nucleofection | DNA | Detection of transfected HLCs in HB mouse |

| F954 Stephens, 2019 | Stem cells | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and Ad platform | Plasmid | Correction of FIX in HB mice |

| F955 Wang, 2020 | Hepatocytes | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | Correction of FIX in adult and neonatal HB mice |

| F956 Ma, 2022 | ESCs | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid electroporation | Plasmid | Detection of FIX at the RNA and protein levels |

| F957 Lee, 2022 | Hepatocyte | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | Detection of FIX in HB mouse model |

| F958 He, 2022 | Hepatocyte | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | Correction of FIX in adult and neonatal HB mice |

| Hemophilia A | |||||

| F959 Sharma, 2015 | Hepatocytes | Gene correction | ZFN via plasmid and AAV delivery system | DNA | Correction of FVIII in HA mouse model |

| F860 Park, 2015 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid electroporation | None | FVIII activity restored in HA mouse model |

| F861 Hu, 2019 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid nucleofection | ssODNs | FVIII activity restored in HA mouse model |

| F862 Park, 2019 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas9 via RNP electroporation | DNA | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| F863 Sung, 2019 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid electroporation | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| F864 Chen, 2019 | Hepatocytes | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in HA mouse hepatocytes |

| F865 Zhang, 2019 | Hepatocytes | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in HA mouse hepatocytes |

| F866 Ramamurthy, 2021 | Placental cells | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in human placental cells |

| F867 Cho, 2021 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| F868 Hu, 2023 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| Gene targeted . | Cell type . | Gene editing . | Nuclease delivery . | Donor . | Results in recipient model . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemophilia B | |||||

| F949 Li, 2011 | Hepatocytes | Gene correction | ZFN via plasmid and AAV delivery system | DNA | Correction of FIX in neonatal HB mouse model |

| F950 Anguela, 2013 | Hepatocytes | Gene correction | ZFN via plasmid and AAV delivery system | DNA | Correction of FIX in adult HB mouse model |

| F951 Lyu, 2018 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid electroporation | Plasmid | FIX secreted in transplanted HB mouse |

| F952 Ramaswamy, 2018 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas 9 plasmid nucleofection | DNA | Correction of FIX in HLCs in HB mouse |

| F9353 Morishige, 2020 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 plasmid nucleofection | DNA | Detection of transfected HLCs in HB mouse |

| F954 Stephens, 2019 | Stem cells | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and Ad platform | Plasmid | Correction of FIX in HB mice |

| F955 Wang, 2020 | Hepatocytes | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | Correction of FIX in adult and neonatal HB mice |

| F956 Ma, 2022 | ESCs | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid electroporation | Plasmid | Detection of FIX at the RNA and protein levels |

| F957 Lee, 2022 | Hepatocyte | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | Detection of FIX in HB mouse model |

| F958 He, 2022 | Hepatocyte | Gene addition | Cas9 plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | Correction of FIX in adult and neonatal HB mice |

| Hemophilia A | |||||

| F959 Sharma, 2015 | Hepatocytes | Gene correction | ZFN via plasmid and AAV delivery system | DNA | Correction of FVIII in HA mouse model |

| F860 Park, 2015 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid electroporation | None | FVIII activity restored in HA mouse model |

| F861 Hu, 2019 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid nucleofection | ssODNs | FVIII activity restored in HA mouse model |

| F862 Park, 2019 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas9 via RNP electroporation | DNA | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| F863 Sung, 2019 | iPSCs | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid electroporation | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| F864 Chen, 2019 | Hepatocytes | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in HA mouse hepatocytes |

| F865 Zhang, 2019 | Hepatocytes | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid and AAV delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in HA mouse hepatocytes |

| F866 Ramamurthy, 2021 | Placental cells | Gene addition | Cas9 via plasmid delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in human placental cells |

| F867 Cho, 2021 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

| F868 Hu, 2023 | iPSCs | Gene correction | Cas9 via plasmid delivery system | Plasmid | FVIII secreted in the iPSCs of patients with HA |

Ad, adenoviral vector; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; ssODNs, single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides.

Gene editing in HB models

Early genome editing studies in hemophilia used ZFN nucleases to correct the neonatal mouse model of HB.49 Li et al targeted integration of an AAV-hF9 into DNA double-strand breaks at the albumin locus, considered a safe harbor site because the insertion of exogenous genetic material in that location does not disrupt cellular function. This strategy was also successful in correcting APTT and restoring hemostasis in the adult HB mouse model with quiescent hepatocytes.49,50

Despite early successes with ZFN, a number of investigators found the CRISPR/Cas9 system to be simpler and more effective. Lyu et al generated iPSCs using peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a patient with HB and inserted CRISPR/Cas9 full-length F9 complementary DNA (cDNA) into a “safe harbor” AAVS1 locus of these iPSCs.51 This led to stable secretion of FIX at 5%. Hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) that differentiated from the corrected iPSCs were then administered via splenic injection into the immunodeficient NOD/SCID mouse model, with only transient FIX antigen detection. The cause of the transient IX antigen detection is unknown but may indicate that the transplanted human hepatocytes were rejected by the newly regenerated mice hepatocytes.

Other investigators have used similar CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing approaches to repair point mutations and in-frame deletions of the F9 gene in iPSCs from patients with HB.52,53 After transfection of the patient iPSCs and subsequent differentiation into HLCs, there was correction of the sequence with no integration events, but no FIX activity was detected. The reason for this finding is not clear, but the authors attributed it to potential differences in donor iPSCs, transcription factors in hepatic differentiation, or epigenetic factors in cellular response.53

To improve FIX expression, a dual AAV vector system, with an AAV8 vector carrying Cas9 and an AAV8 carrying the hyperactive Padua IX variant has been studied. After coinjection of these dual vectors into neonatal and adult mice with HB,54 there was stable FIX expression, with a mean of 171.6%, for 8 months. To assess the Padua IX variant incorporation, two-thirds partial hepatectomy was performed 8 weeks after Padua IX delivery in neonatal mice with HB. All mice survived with good postoperative hemostasis and a mean peak of 147% FIX level for 24 weeks, confirming stable incorporation of this Cas9 system.

Other studies have used a CRISPR/Cas9 approach to insert mF9 or hF9 to correct the HB mouse model,55-58 achieving phenotypic correction, with FIX levels sufficient to provide hemostasis, from 4% to 20%, for up to 48 weeks. This was true whether the CRISPR/Cas9 gene delivery was via adenoviral55 or AAV vector58 or plasmid electroporation56; whether the gene insertion was into a safe harbor/locus with the genome55; or whether the targeted tissue was an embryonic stem cell56 or hepatocyte.57,58 The site of editing was considered important for optimal gene expression in the liver, specifically, gene editing into transcriptionally active genes in the hepatocyte, for example, the transcriptionally active apolipoprotein C3 gene57 or the endogenous promoter 3′ untranslated region of the albumin gene,58 enhanced gene expression in the liver.

Gene editing in HA models

Although the earliest HA gene editing studies used ZFN nucleases to achieve site-specific integration of the F8 transgene and long-term expression in the mouse with HA,59 similar to long-term FIX expression in the mouse with HB by the same approach,59 the simpler, more efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system commonly used for F8 gene editing.60-68 The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing approach has been used to repair F8 inversion mutations, including intron 1 and intron 22 inversion mutations,60,62,63 in-frame and large deletions mutations60-63,67 in iPSCs from patients with HA. Whether using full-length F8 cDNA or the smaller more simply packaged BDD-F8 cDNA61,64,65; targeting iPSCs,60-63,67,68 hepatocytes,64,65 or placental cells66; using EF1a63 or hAAT68 promoters; delivering via AAV64-67 or adenovirus vector or plasmid electroporation60; integrating the gene into the albumin locus64 or safe harbor sites62,66; or repairing inversion60,62,63,68 or deletion mutations,60-63,67 the CRISPR/Cas9 F8 gene delivery approach has, with few exceptions, successfully achieved expression of the F8 transgene in mouse models, with FVIII expression ranging from 10% to 400%, for up to 2 years, with hemostasis in tail clip assay.

In at least one instance, there was a discrepancy in FVIII expression between 2 studies using the same cell type and the same transgene.62,63 Specifically, studies by Park et al and Sung et al targeting endothelial cells and using the BDD-F8 transgene, each showed expression of the F8 transcript, but in the latter study, no active FVIII protein was detected. The reason for the difference in outcomes in the 2 studies is unknown, but it has been suggested that modifications in the F8-coding sequence might improve the transcription and secretion properties of the F8 gene system.63

Another consideration has been the site and cell type of FVIII synthesis on the level of FVIII expression. Because endothelial cells, but not hepatocytes, express FVIII, it has been suggested that optimal F8 gene editing using hepatocytes requires site-specific editing in a particular locus, such as the albumin locus. In fact, the highest levels of FVIII expression, up to 400%, with hemostatic correction, persisting for up to 2 years was reported in a study of BDDF8 hepatocyte delivery to the Alb locus in the HA mouse model.65 Optimizing hepatocyte expression of FVIII continues to be an ongoing area of interest.

These preclinical gene editing studies confirm the efficiency of delivery of the gene editing machinery over transfection via vector-based platforms and the greater efficiency of F9 and F8 delivery via CRISPR/Cas9 over ZFN strategies, with functional correction in mice with HB and HA for up to ≥1 year. Although these studies of gene editing show promise, many safety and ethical issues remain, including potential off-target effects and accuracy with the CRISPR system.

It is noteworthy that greater precision and specificity is becoming possible with the use of base editing and prime editing.69-71 Base editing can make point mutations, G>A, A>G, and T>C, at targeted locations in genomes of human cells, without requiring double-stranded breaks but is limited by the number of insertions, deletions, or transversions that can be made. For example, base editing cannot be used to perform the 8-transversion mutations to correct the commonest cause of sickle cell disease, the 4-base duplications that cause Tay-Sachs disease, or the 3-base insertions to correct the commonest form of cystic fibrosis.69 In contrast, a more recent editing technique, prime editing, can replace, insert, or delete DNA sequences at targeted locations in genomes of human cells, without requiring double-stranded breaks. Instead of Cas, it uses prime-editors, which include a prime editor protein, a reverse transcriptase, a prime editing guide RNA, which specifies the target site, and a programmable RNA template to specify the desired DNA sequence change, with much lower off-target activity.71 Future use in humans will require careful attention to safety, immunogenicity, and off-target effects.

Summary

Significant scientific developments in novel RNA technologies in hemophilia models appear to show advantage over factor-based products and AAV gene therapies. Preclinical studies of RNA-based technologies, if proven safe, effective, and durable in future clinical trials, will provide promise not only for those burdened by current treatment but also for those in resource-poor settings in which adequate therapies are scarce and poor outcomes common. Importantly, what is learned will have potential broad application to other diseases, including liver disease and other inherited disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Health Resources and Services Administration Region III Federal Hemophilia Treatment Centers Grant 230HC MC24050-11-00 subaward No. 3209610516-P (M.V.R.), Pennsylvania Department of Health State Support of Hemophilia Center of Western PA SAP #4100079797 (M.V.R.), and National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL124021 and R01 HL122596 (S.Y.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.V.R. developed the concept, designed the tables and graphics, and wrote the manuscript; and S.Y.C. helped in writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.V.R. receives research funding to her institution from BioMarin, Sanofi, SPARK, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals and serves on advisory boards of BeBio, BioMarin, HEMAB Biologics, Sanofi, SPARK Therapeutics, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. S.Y.C. has served as a consultant for Merck and United Therapeutics; serves as director, officer, and shareholder of Synhale Therapeutics; and has filed patent applications regarding RNA targeting in pulmonary hypertension.

Correspondence: Margaret V. Ragni, Division Hematology/Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania, 3636 Blvd of the Allies, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-4306; e-mail: ragni@pitt.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal