In this issue of Blood, Roeker and colleagues explore pirtobrutinib combination regimens in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1 Few debates in cancer medicine are as old as the debate between single-agent therapy vs combination therapy.

Nearly 40 years before the first introduction of “chemical-therapy” for cancer, Paul Ehrlich was already envisioning combination regimens. After first discovering salvarsan for the treatment of syphilis, and introducing the term “chemotherapy,” he wrote in 1907:The fact that by frequently repeated administration of not completely sterilizing doses, there is gradually acquired a resistance to the substance in question, makes it especially desirable that the first onslaught should be as complete as possible. This object, from what I have previously said, may probably best be achieved by a suitable combination of substances.2

As cancer chemotherapy developed in the 1950s and 1960s, the sequential use of monotherapies was customary. When Frei and Freireich developed the VAMP (vincristine, amethopterin, mercaptopurine, and prednisone) combination chemotherapy regimen at the National Cancer Institute, the medical community was aghast. Outright insubordination among house staff at the Institute and prominent disagreements with hematologic luminaries, such as William Dameshek, were notable.3

The treatment of CLL was not immune to this controversy. After fludarabine displaced chlorambucil, attention turned to combination therapies. Fludarabine + cyclophosphamide was shown to be more effective than fludarabine alone. After the introduction of rituximab, the fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab regimen was shown to be superior to fludarabine + cyclophosphamide in the first CLL study to demonstrate an overall survival benefit in CLL.4

The introduction of novel targeted therapies in CLL has rekindled the debate. After ibrutinib displaced both fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab and bendamustine-rituximab, the logical next step was the addition of rituximab to ibrutinib. However, this combination showed no benefit in 2 well-designed phase 3 studies. Despite these negative studies, the addition of obinutuzumab to acalabrutinib was shown to be superior to acalabrutinib monotherapy, rendering the Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK)/CD20 combination controversial.5

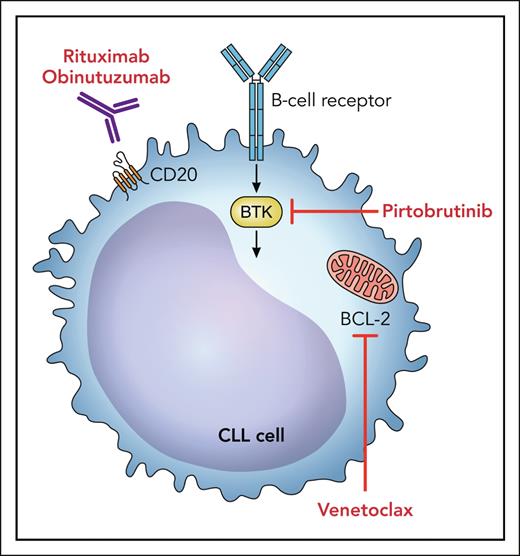

B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitors have demonstrated remarkable activity in the treatment of CLL and were approved for use based on studies that partnered venetoclax with anti-CD20 antibodies in the frontline and relapsed settings. Naturally, there was interest in an oral regimen combining BTK and BCL-2 inhibitors (see figure). When venetoclax was initially added to ibrutinib in a randomized phase 3 study in an elderly population,6 the toxicity seen with the combination dampened enthusiasm for the regimen, leading to a varying approval status globally. For example, the combination is included in National Comprehensive Cancer Network regimens but has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Potential targets for combination therapy with pirtobrutinib include BCL-2 inhibitors and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Potential targets for combination therapy with pirtobrutinib include BCL-2 inhibitors and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Circling back to Paul Ehrlich, resistance develops among CLL patients treated with BTK monotherapies. Resistance mutations, such as C481S, T474I, and L528W, are now commonly recognized in patients with resistance to the first- and second-generation covalent BTK inhibitors.7 Provocatively, Jain et al demonstrated how the combination of a BTK inhibitor with a BCL-2 inhibitor may alter the landscape of relapsed disease, with a notable absence of mutations commonly associated with covalent BTK monotherapy, once again kindling the debate for intelligent combinations.8

The third-generation BTK inhibitors, such as pirtobrutinib, have efficacy against CLL even in the presence of common resistance mutations. Results of 2 large, randomized phase 3 studies on patients with relapsed CLL are expected soon. Despite the novel mechanism of action and the high rates of initial response, the durability of responses to pirtobrutinib after prior covalent BTK inhibitors is modest and additional BTK mutations have been shown to confer resistance.7 Extrapolating from previous BTK/BCL-2 combination studies, it is therefore logical to speculate that adding venetoclax (or perhaps other active agents) to pirtobrutinib may improve the durability of disease control over monotherapy.

Roeker et al have combined pirtobrutinib with venetoclax (PV), with or without additional rituximab (PVR). They demonstrated that this combination is both well tolerated and has impressive activity. The overall response rates were 93.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 68.1% to 99.8%) for PV and 100% (95% CI, 69.2% to 100.0%) for PVR, with 10 complete responses (PV, 7; PVR, 3). After 12 cycles of treatment, 85.7% (95% CI, 57.2% to 98.2%) of PV and 90.0% (95% CI, 55.5% to 99.7%) of PVR patients achieved undetectable minimal residual disease in peripheral blood by clonoSEQ assay (Labcorp, Burlington, NC) at a sensitivity of <1 × 10−4. Progression-free survival at 18 months was 92.9% (95% CI, 59.1% to 99.0%) for PV patients and 80.0% (95% CI, 40.9% to 94.6%) for PVR patients. This phase 1B trial has provided the key combination data for a large registration study that is currently enrolling patients. In the forthcoming study, patients with relapsed CLL will be randomly assigned to venetoclax and rituximab, with or without the addition of pirtobrutinib. Paul Ehrlich, the remarkable visionary whose work helped set the stage for cancer medicine, would likely be pleased that we are still pursuing his ideas over 100 years later.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.P.S. has performed consulting work for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genentech, and Lilly.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal